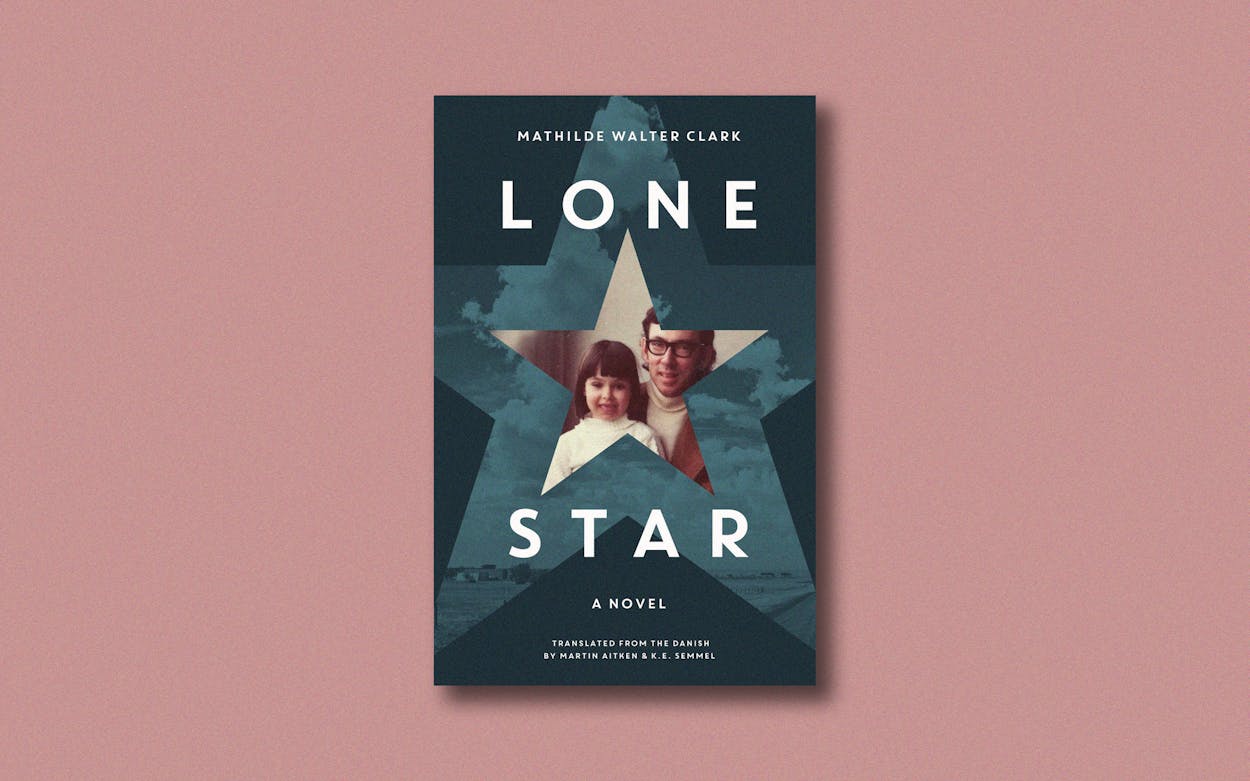

Read Mathilde Walter Clark’s Lone Star

“In a way, I’m from here.” That’s how Mathilde Walter Clark, author and narrator of the forthcoming novel Lone Star, explains her decision to reconnect with her estranged father in his native Lockhart. Perhaps as much memoir as fable, the book opens with the death in Copenhagen of the author’s stepfather. Convinced by the loss that no one would call her should her biological father die, she suggests to him that they convene in Central Texas. Half Danish, half multigenerational American, she finds herself an object of curiosity in our state even though her relatives are scattered across these ranchlands and her ancestors are buried beneath them.

Clark explores and confronts our “oft-mythologized landscapes” and customs in a manner reminiscent of Joan Didion (and rendered exquisitely by translators Martin Aitken and K.E. Semmel): at once romantic, inquisitive, and honest. With an anthropologist’s detachment she remarks upon a “Firearm Check-in Station” and the bounty of H-E-B; she digs tenderly into her ancestors’ complicity in Texas’s slave trade and erasure of Indigenous peoples. “Americans didn’t wish for something, I noted, they wanted,” she reflects, one of her very few observations that feels tinged with condemnation. But then she recounts, in a reverie, the sensation of finding oneself alone on a wide-open highway ringed with wildflowers. She discovers, as she hopscotches the Hill Country, that Texan strangers embrace her more freely than even some of her European kin. Ultimately, Clark concedes, when it comes to family and to local lore, there can be love in myth.

Amid the topsy-turvy dog days of 2021, Lone Star might be just the book to help readers find their footing. Anyone who has lived through the chaos and grief of the past year is bound to see themself in this “novel about distances.” Those who’ve spent a pandemic far from kin will recognize especially the relief of familial reunion. But for Texans, there is perhaps a more complicated catharsis in these pages. At a moment in which our discourse increasingly is marked by ideological entrenchment, Lone Star provides an opportunity to examine anew our state’s legendry. “The longing for what was lost seems to be felt with a more intense ferocity [in Texas],” Clark writes, as she asks us to see our history, and ourselves, through fresh eyes. — Alicia Maria Meier, assistant editor

Enjoy Comadre Panaderia’s Pan Pari

Mariela Camacho is a font of Mexican pastry knowledge and Texas is better for it. After initially establishing her Comadre Panaderia pop-up in Seattle in 2018, she moved home to San Antonio in 2019 to reenvision her dream of a Mexican baked goods start-up. She began with weekly pop-ups across “River City” in March 2020 and transitioned to pastry deliveries that will soon expand to Austin, where she recently relocated. The Comadre Panaderia pop-up has found a semipermanent home at Nixta Taqueria on Austin’s East Side. Each Saturday, from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m., Camacho’s operation sets up in Nixta’s westward-facing backyard. Purchases are walk-up only, and she offers six creative standards, including an ever-changing array of flavored, pillowy-soft conchas and savory empanadas, as well as thin flour tortillas.

This week, Comadre Panaderia’s specials include Gansitos (chocolate-coated and sprinkle-topped candy bars filled with layers of cream and berry preserves); smoky sourdough loaves with morita chiles and garlic; a coconut-and-lime concha; and surprises Camacho wouldn’t divulge during a phone conversation. I’m crossing my fingers for fruity pingüinos (similar to Little Debbie–brand cream-filled chocolate cupcakes). There are thirteen items to choose from, not including aguas frescas. Line up early. But don’t fret if you miss out on the exquisite Mexican pastries and tortillas: Comadre Panaderia also takes custom orders for cakes and other treats. — José R. Ralat, taco editor

Read Sandra Cisneros’s Loose Woman

The poetry in Loose Woman, a collection from Sandra Cisneros originally published in 1994, begins before page 1, in her acknowledgements. She lists her loved ones under four categories: eyes, voice, heart, and spirit. It’s a thoughtful, tender way of organizing one’s relationships. But it’s the only gentle moment in the volume of sixty poems.

Instead, Cisneros writes as if she were sitting on her front porch, boots kicked up, and brandishing a shotgun. With rock-solid tenacity, Cisneros writes about race, gender, and heartbreak. The author of The House on Mango Street and recipient of the Texas Medal of the Arts, Cisneros has spent much of her life in San Antonio, and she takes note of one of her neighbors in “Black Lace Bra Kind of Woman”: “Drive her ’59 seventy-five on 35 / like there is no tomorrow … Thirty years pleated behind her like / the wail of a San Antonio accordion.” Elsewhere, she delves into her Mexican American psyche: “I have to run up the aisle and ask for a U.S. citizen form because / I’m well how do you explain?” Throughout, she wallows in heartbreak, as in my favorite poem—one I find myself returning to more often than I should admit—“I Am So Depressed I Feel Like Jumping in the River Behind My House but Won’t Because I’m Thirty-Eight and Not Eighteen.” Cisneros has a new novella, Martita, I Remember You/Martita, te recuerdo, coming next month, and before she clobbers us again, I recommend getting walloped by Loose Woman. — Leah Prinzivalli, associate digital editor

- More About:

- Books

- Mexican Food