Last January, just after Austin’s Westlake High School had beaten Houston’s North Shore in the state football semifinals and while the Gap Band’s “You Dropped a Bomb on Me” blared inside his team’s locker room, Westlake coach Todd Dodge stole glances at his phone. He had to check scores.

Dodge’s Westlake Chaparrals would play the winner of the matchup between Southlake Carroll and Duncanville—both from the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex—for the state championship in the toughest division of Texas high school football. The clock ticked as Southlake clung to a late lead, and before long, the final was set. Westlake versus Southlake. Goliath versus Goliath. Meanwhile, the teenagers in the locker room kept dancing to their coach’s favorite funk music.

Dodge’s phone rang. It was his five-year-old grandson, Tate. “We finally beat Duncanville,” the boy said. “Now we’re comin’ for you, Paw Paw.”

Dodge laughed. Later that weekend, he called his son, Tate’s father Riley—the then-32-year-old head coach of the Southlake Carroll Dragons. There was no talk about how unlikely it was that they’d be coaching against each other for the state championship. They didn’t marvel over the implausibility of its happening between Westlake and Southlake, two schools that meant so much to their family. They didn’t mention Ebbie Neptune, Riley’s grandfather and Dodge’s father-in-law, who’d built Westlake athletics from nothing. They didn’t speak of the state title game between the same two teams fifteen years earlier, when Dodge was coaching the Dragons and Riley was his quarterback. That 2006 game was the only time Neptune, who had recently retired after 34 years at Westlake, ever rooted against his Chaparrals. “Blood is thicker than water,” Riley recalled his grandfather telling a reporter as Dodge, Riley, and Southlake went on to win their third straight championship together.

Back in January, Dodge and Riley didn’t mention any of it. That week before their teams played each other, father and son talked referees. They needed to agree on an officiating crew for the big game.

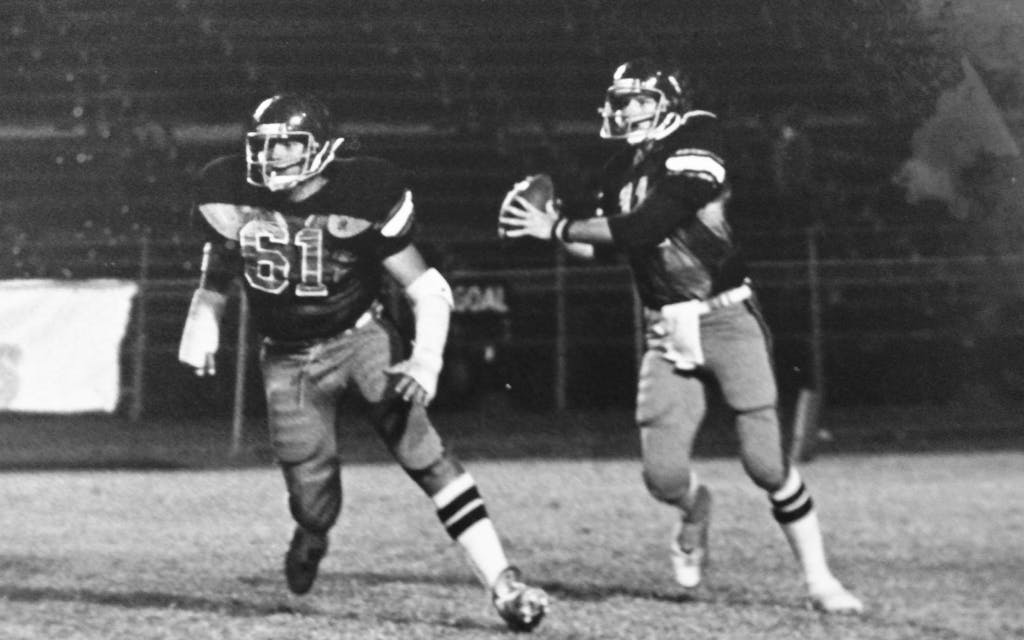

There may be nobody in this gridiron-crazed state who has lived the football life more completely than Todd Dodge. Longtime fans know about his 1980 senior year at Port Arthur’s Thomas Jefferson High School, when he became the first Texas schoolboy to throw for more than 3,000 yards in a season. Others know him as the former University of Texas quarterback who led the Longhorns to a number one national ranking in 1984.

Most Texans, however, know him as a coach. He is almost certainly the best in high school football today. He is arguably the greatest of all time. (He might have to settle for second-best when it comes to coaches, at any level, produced by Jefferson, thanks to class of ’61 grad and Pro Football Hall of Famer Jimmy Johnson.) Now 58, Dodge will retire after this season—his eighth at Westlake—and he hopes to capture a third consecutive state title along the way. He’s already won six in his coaching career, and if his team remains undefeated through the playoffs, he’ll retire with a high school win-loss record of 234–72. On paper, the Chaparrals are favored to do just that, led by Clemson-bound Cade Klubnik, the nation’s top high school quarterback and the latest in a line of Dodge-mentored signal-callers that includes NFL players Chase Daniel and Sam Ehlinger, along with former Alabama star Greg McElroy.

WATCH: Now in his final season before retirement, Todd Dodge is looking to add one more trophy to his mantel.

Dodge’s calling card is his offense. From 2002 to 2006, he steered Southlake Carroll to four championships and compiled a 79–1 record, dropping that lone defeat by a single point in the 2003 state final. Back then, when teams throughout Texas still played slow, power-run football, Dodge’s Dragons never huddled. They spread five receivers across the field and threw more passes in a quarter than some opponents attempted in entire games. Other teams tried to wear you down; Dodge’s just ran by you. Once, Dallas Cowboys head coach Bill Parcells called to ask Dodge to interview to be the team’s tight end coach. Problem was, Dodge’s system didn’t use a tight end.

But offensive advantages don’t last long in football. These days, elements of Dodge’s spread offense are common at all levels of the sport, yet his teams still dominate. And to hear the coach and his acolytes tell it, his real genius lies off the field. “It’s one thing to be a great coach,” said Ehlinger, who played for Dodge at Westlake from 2014 through 2016. “It’s another to be a great man. You know the quote ‘Ability takes you to the top, but character keeps you there’? Coach Dodge perfectly embodies that.”

What’s the secret to his success? When I visited his office one afternoon this fall, Dodge laughed at the question. “People always talk about ‘God, his system!’ ” he said. “I’m not so sure what all is original in life or in football. I think sometimes people take someone else’s plan and execute it better than where they got it.”

Take his goal board, a simple list of aspirations such as “No three-and-outs” and “Allow fewer than 75 rushing yards.” They are basic tenets of football, but Dodge’s magic is convincing teams to treat them as though they’re the Ten Commandments. At a recent game, ahead 56–0, the Chaps offense faced a third down with 26 yards to go. The game was in the bag, and the play couldn’t have mattered less. “Goal board!” yelled a player on the sideline. “No three-and-outs!”

Dodge tells stories in pregame meetings, like the one about a bulldog who was bullied by bigger bird dogs but kept barking at his foes, challenging them until he drove them away. The players compress these parables into a kind of code. Just say “bird dog, bulldog,” and they’ll know you’re reminding them to be relentless.

He was only fifteen, and he felt as if he had to choose between family and football. He chose football.

The guiding light of Dodge’s philosophy is typed in all caps at the bottom of every schedule and game-plan printout he gives his teams: “FAMILY.” He frequently tells his players he loves them. When he coached Southlake, after two-a-day practices, he’d lead the team into the weight room and spend hours sharing stories about his life while they told him about theirs. Parents call him when they’re not sure how to discuss thorny subjects with their kids, which is why players planning to attend house parties often receive a reminder from Dodge to act responsibly. He approaches each season as if he’s building a group of brothers incapable of quitting on one another.

That last trick Dodge didn’t need to borrow. His whole life has been an extended lesson in how closely linked family and football can be. In that sense, perhaps it was inevitable that he wound up coaching against his son in last season’s state championship. “I just can see what the Lord has done with my life,” Dodge said. “I sit here and go, ‘If you didn’t believe that this guy was going to be a football coach because of the situations he was put into . . . ’ ”

He trails off, looking in the direction of a trophy he won back in high school.

Port Arthur, where the Texas coast meets the Louisiana state line, is the type of place where kids don’t have to ask what their friends’ dads do for work; once young men finish high school, most head to the oil refineries. But first they become Jefferson Yellow Jackets. The program had won two state championships when Dodge started high school there in the late seventies, but decades had passed since the last of those triumphs.

When he started middle school in Port Arthur, Dodge realized he wasn’t like his classmates. He was the new kid; his dad was a Methodist minister, and the family moved often. But one thing Dodge did share with his peers was football. Once, while living in Garrison, an East Texas town about twenty miles outside Nacogdoches, a six-year-old Dodge wandered onto the practice field for the Garrison High School Bulldogs—and kept coming back until the coach made him their ball boy. Neither of Dodge’s parents understood their son’s attraction to the game, especially his father, who wasn’t a sports fan. But in third grade, when Dodge brought home a flyer for youth football, they signed him up. From the beginning, he played quarterback.

In the spring of 1978, Dodge’s freshman year at Jefferson, the school hired a new coach, former Yellow Jacket Ronnie Thompson, to restore some pride in the football team. That season, Thompson called up Dodge and three other freshmen to practice with the varsity. It was like enrolling third graders in precalculus, but he did it to see how they’d respond and to grow them into leaders. Halfway through his sophomore season, Dodge became the starting quarterback. The Yellow Jackets managed one win that year.

Then, shortly after football season ended, Dodge’s father learned he’d been transferred to a congregation in Longview, about two hundred miles north. Time to pack bags, say goodbye, and start over. Again.

Port Arthur had been the first place Dodge had ever considered home. When he broke the news to his teammates, they wondered how they’d manage without their first-string quarterback. That’s when Richard Rice, a junior offensive lineman, spoke up: “Why don’t you live with us?” If Dodge left with his family, transfer rules at the time would have prevented him from playing varsity football his junior year; if he stayed, he wouldn’t have to sit out. He was only fifteen, and he felt as if he had to choose between family and football.

He chose football.

The Rices didn’t have much extra space, but they squeezed another bed into Richard’s room for Dodge. To keep him enrolled at Jefferson, the Rices became his legal guardians. His parents agonized over the decision, but they believed it was best for Dodge and found ways to keep in touch with their son. In Longview, Dodge’s mom taught eighth grade math and convinced her principal to give her the last period of the week free so she and Dodge’s father could make the long drive to watch their son play.

Of that Port Arthur squad, Dodge said, “They were family to me.” Teammates would show up unannounced at the Rice home, climbing through the boys’ bedroom window even though the front door was always open. Rice would shake Dodge awake before dawn, yelling, “Get up! We’re going crabbing,” and they’d drive to a spot called Pleasure Island to throw chicken necks in the water and see what they could pull up. They’d bring the catch home to Mrs. Rice, and she’d turn it into gumbo or crab stew.

Then there was Thompson. “He was the shot caller in my life,” Dodge recalled. “He was father.” The coach knew everything Dodge did, knew when to discipline him and when to love on him. One day, during a grueling week of practices his freshman year, Dodge couldn’t bear the thought of heading back onto the field. So, during second period, he told his teacher he felt ill. When the nurse took his temperature, Dodge rubbed the thermometer on his leg while she wasn’t looking and got it up to 101 degrees. She sent him home and the day melted away—until, around 3 p.m., he heard a knock at the door.

“Get in the truck,” Thompson said. The coach didn’t know that Dodge had faked the fever. It didn’t matter. “Don’t you ever do that s— again,” he said.

Dodge didn’t tell anybody, but by the time he was through playing for Thompson, he’d made up his mind: he wanted to be a football coach.

Outside, on a warm Friday night this past September, the air was thick with the noisy anticipation that precedes a Westlake football game: the band warming up, old friends hugging and shaking hands, cheerleaders shouting, “Let’s go, blue! Let’s go, red! Let’s go, white! Fight! Fight! Fight!”But inside the Chaps locker room, a few minutes before the home opener, nobody said a word.

Dodge is short for a former quarterback, five-eleven, with graying black hair and a face pink from afternoons spent on the football field. When he stood to address the team, all the players straightened in their seats. “I’ve been doing this for thirty-six years,” he said, “and I still get goose bumps.” It was standard coach-speak at first: “Don’t you worry about doing anything except staying in the moment.”

Then he paused. His voice grew louder. He was preaching now. “Love one another,” he said. “Defense is the brother of our offense. The kicking game is the brother of all of us. We say ‘family’ all the time. That is not just some word to me. I’m hoping it’s not to you.

“Get that little twinkle in your eyes, boys,” he said. “Play fair. Play tough.” The players popped out of their chairs and grabbed their helmets.

“Let’s get ’em,” Dodge said. “Let’s go. ‘Family’ on three.”

“One, two, three—

“Family!”

They ran outside, Dodge in front. When he passed through the red archway that reads “Ebbie Neptune Field,” he made a point to look up and touch that name—that piece of his family—just as he always does.

West Lake Hills sits just outside Austin, and though it’s now dotted with the mansions of tech billionaires, the suburb still exhibits the quirks of a small town—especially when it comes to Chaparral football. In the Chaps, the Westlake that now counts Matthew McConaughey and Michael Dell among its residents remains connected to the place where Dodge’s father-in-law moved in 1969—when most locals were cedar choppers and an Army veteran like Neptune could still purchase a home for $40,000 financed through the GI Bill. These days, team photos plaster the walls of restaurants, yard signs outside homes brag that a defensive tackle lives within, and cheerleaders decorate players’ cars (“#94 on the field, #1 in our heart!”). Dodge feels most comfortable in towns sick with football fever. They remind him of Port Arthur.

At Jefferson, Coach Thompson needed only three years to stoke the city’s frenzy for the Yellow Jackets, with Dodge leading an aerial attack in 1980 that took the team deep into the playoffs and broke nearly every passing record in state history. Back then, when Dodge and Rice would eat at the Fish Net, they’d usually find that some other customer had paid for their fried crab balls. Rice’s mother kept a scrapbook from those years, including a write-up in Sports Illustrated noting that Dodge had thrown for 3,137 yards his senior season, which ended with a loss to Odessa Permian in the title game. Soon thereafter, Dodge was whisked to New York City to receive the Hertz #1 Award, given to the top high school athlete in each state. O. J. Simpson, who emceed the ceremony, handed Dodge his trophy. The honoree from North Carolina was a basketball player named Mike Jordan.

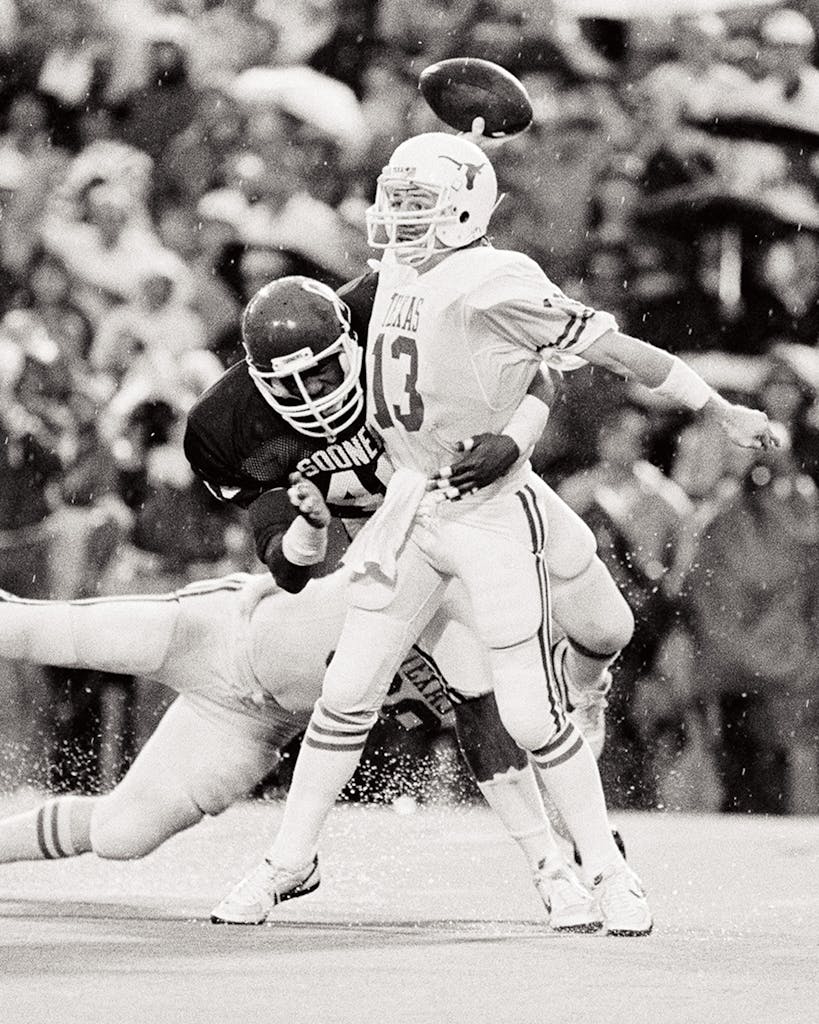

Then it was off to the Forty Acres, as the UT-Austin campus is known. Dodge’s UT career was uneven. As a sophomore in 1983, Dodge shared the starting quarterback role with Rick McIvor and Rob Moerschell on a Longhorn team that lost to Georgia in the Cotton Bowl. Dodge began his junior year as the sole starter, beating number eleven Auburn and number four Penn State in the first two games of the season. The Horns became the top team in the nation—and halfway through the year they were 6–0–1 when he opened a game against Houston by throwing thirteen straight incomplete passes. He was benched.

At one game during his senior year, the stadium in Austin filled with boos when the public address speaker announced Dodge’s return to the starting lineup. He wound up throwing for 359 yards that day—a single-game school record that stood for thirteen years—and ran off the field to a standing ovation. “Playing quarterback at the University of Texas, there could not have been a better preparation ground for being a coach because of all the good, bad, and ugly that you’re going to go through,” he recalled. “I learned how to handle success. I learned how to handle injury. I learned how to handle doubt. I learned how to handle failure. My career had all of those.”

There were nights when Dodge wouldn’t leave his apartment—he preferred to avoid confrontation with any overzealous Longhorn fans. But one evening during his junior year, friends persuaded him to go to a sports bar, and while he nursed a beer, he met a UT junior named Elizabeth. Right away, Dodge felt something like peace with her. Elizabeth, from Westlake, was outgoing and bright—a tall brunette with a big smile. Before long, they were dating, and one night, she said they could drive her father’s car to dinner. Dodge took the wheel, and on the way, a driver rear-ended them. “The trunk was sitting in the back seat,” he recalled. That’s how Dodge met Elizabeth’s father,

Ebbie Neptune.

Neptune already knew about Dodge. Neptune coached football at nearby Westlake, and in Chaparral athletics he’d found his life’s mission. When the school first hired him as offensive coordinator, in 1969, the team didn’t have a home field and played every game on the road. When construction finally finished on Chaparral Stadium, he watered the grass by hand. “If I don’t get fired,” he told a friend, “this is where I want to retire.”

He got the head coaching job in 1982—not long after Dodge began his career at UT. Neptune and Dodge were kindred spirits: Texas Coast boys, fiercely loyal football stars who loved to laugh. It wasn’t long before Neptune was defending Dodge at Longhorn games; once, when a group of fans heckled the quarterback, Neptune walked over and told them he didn’t appreciate them using such language about his daughter’s boyfriend.

Before Dodge’s senior season, after he took Elizabeth out on a date, the couple sat gazing at the UT football field from the hood of his car in the stadium parking lot. That’s when he asked her to marry him. They were wed the following year at the Methodist church on campus. Dodge’s father conducted the service, and nearly every groomsman was an old Jefferson Yellow Jacket.

NFL teams didn’t show much interest in an undersized quarterback like Dodge, and because he knew he wanted to coach after graduation, Neptune brought him on as a student assistant at Westlake for the 1986 season. It was Neptune’s final year coaching the Chaps before becoming the school’s athletic director. Westlake had just been elevated to the state’s top division, and the transition was sure to be brutal. But while the Chaps lost game after game, Dodge kept giving pointers to quarterbacks and receivers.

Before the season’s final contest, Dodge found the five senior captains and handed them a single handwritten letter. “Captains, I know this has been a hard and long season for all of you,” it began. “I’m writing this because I’ve observed this team all year and it has bothered me to see you guys fight hard game in and game out only to come up short at the end. Well, I’ll tell you what. It doesn’t have to be that way tonight . . . If y’all walk out on that field tonight as one and not as 45, there is [no] way you will lose.”

Westlake did lose, but those captains saved the letter. They made photocopies so all five of them could keep one. Even then, players sensed there was something special about Coach Dodge.

After the season with Westlake, Dodge bounced from one school to the next in various assistant coaching gigs. By the time he was 31, he earned his first head coaching position, about sixty miles northeast of Austin at C. H. Yoe High School, in Cameron. He and Elizabeth had two children by then, 5-year-old Riley and newborn Molly. Elizabeth was still completing her master’s in education at the University of North Texas, so she and Molly stayed behind in Denton to finish the semester while Dodge took Riley to Cameron for spring football.

Coaches often say they “live in the field house,” meaning they spend hours studying game tape and scouting opponents. When Dodge and Riley got to Cameron, they actually lived in the school’s practice facility. Dodge slept on the couch. Riley took a cot. “You can’t live like this,” the school board president pleaded with them. But they loved it. Father and son would wake up every day and shower in the locker room. At practices, Riley was the ball boy, and afterward, he’d sit in his dad’s office and watch Dodge break down tape.

The family found more traditional housing once Elizabeth and Molly moved down, but even though Riley could no longer call his father’s office his bedroom, he still attended almost every practice. He loved sitting in on strategy sessions with Dodge and his assistants, and before long, he wanted to learn to throw the ball. One of the keys to training young quarterbacks is teaching them to throw “over the top,” releasing the ball above their shoulder rather than sidearm. So Dodge made Riley stand on one side of Elizabeth’s Chevy Lumina, his eyes barely peeking over the hood. Riley threw each pass using the car as a cue for how high his arm should be. (And when he grew, Elizabeth got a Tahoe.)

Around that time, Riley started to draw plays. He couldn’t have been older than five, and they didn’t all make sense, but he drew X’s and O’s wherever he could. One Sunday in church, Riley scrawled a passing scheme on the back of the bulletin. It had three receivers to one side, two of them running deep and crossing paths downfield. “What do you think about this?” he asked his dad. Elizabeth scolded them for talking during the service.

That happened to be the week that Yoe was hosting its district rivals, the Rockdale Tigers. The lead seesawed back and forth, and Riley assumed ball boy duties until the half—well past his bedtime—when Elizabeth took the kids home. Late in the game, Yoe had the ball and needed a touchdown to win. Dodge called a play for two receivers to run deep before crossing paths. Touchdown.

When Dodge got home, he went to kiss Riley goodnight. The lights were off. He thought his son was already asleep, but right before he left the room, Riley spoke up. “Did you run my play?”

“I sure did,” Dodge said. “Called it the Riley Special.”

In those years, Dodge seemed no different than any other early-career coach—he jumped from school to school, and his teams never had a winning record. But Bob Ledbetter, the athletic director at Southlake Carroll, noticed how well Dodge’s teams played against the Dragons. He called Dodge and asked him to drop off a résumé.

“I can’t get the Southlake job,” Dodge said.

“Todd, I’m hiring the football coach,” Ledbetter said. “I want your application over here, on my desk, by four o’clock.”

Dodge got the job, and from his first season with the Dragons, in 2000, Riley hung around the team. After practices, the preteen would throw routes to receivers. “He had a cannon for an arm,” Kyle Brown, a former slot receiver, once told a reporter. “He executed the Southlake Carroll offense as a seventh grader,” Dodge recalled, “probably better than it’s ever been executed.”

Southlake wasn’t the only school that was special to Riley. He had a teddy bear in his room with a red-white-and-blue Westlake jersey, a gift from his grandfather. Neptune was close to all his grandchildren, but his bond with Riley was unique. “He was my best friend,” Riley said. Several times a year, Riley’s grandfather would invite him to Chaparral games. Neptune would drive north on Interstate 35 and pull over halfway to Southlake at the Czech Stop, famous for its kolaches. Elizabeth would drive Riley down and meet her father in the parking lot, where Riley would climb out of his mother’s car and into Neptune’s back seat for the trip back to Westlake.

Riley loved those handoffs. On Fridays during football season, he was the Chaps’ ball boy. During summers, he’d attend youth football camps at Chaparral Stadium. Neptune took him to coaching conferences, where Riley listened to play-callers from across Texas discuss offensive strategy. “They could have written ‘Coach’ across his forehead,” Ronny Pinckard, Neptune’s friend, said of the boy.

Before long, Riley was a freshman quarterback on Dodge’s Southlake team. At first, the coach made a point of proving he wouldn’t play favorites. Riley recalled waiting for his turn to throw during one practice, when his father suddenly turned to face him. “What did you just say to me?” Dodge asked.Riley hadn’t said anything, but there was a point to be made, and soon he was running sprints in front of the whole team.

Later that year, an old friend approached Dodge at a coaching convention. The friend didn’t know what was happening at practice, only that Riley was on the team. “I’ve coached my three sons, and they’ve all been quarterbacks,” he said. “Someone once told me, when you’re his coach and you’re his daddy, you’re the two most important people in his life. Don’t rob him of either one.”

“That message, it was perfect for me,” Dodge said. “I was robbing him of both.”

Riley started at quarterback as a junior, in 2006, and for the most part, football and fatherhood stayed separate. The Dragons went undefeated until the state finals, where they met Westlake. Riley knew all the Chaps players from football camps he’d attended as a kid. In a playoff game weeks before the championship, he’d broken two ribs and sprained an ankle, so on the biggest night of the year, the usually mobile quarterback stood in the pocket like a statue. His adrenaline mostly shielded him from the pain, but he was dehydrated midway through the fourth quarter when he looked over the Chaps defense and recognized an incoming blitz. He called out a new play at the line of scrimmage, took a few steps forward, and then leaned over and vomited through his face mask. The play clock kept running, and he knew he had the perfect counter for the blitz. Riley stepped back, called “Hike,” and threw a 29-yard touchdown pass. He ran off the field, and Dodge ran onto it, meeting his son halfway to make sure he was okay. Riley didn’t miss a play the rest of the game, and Southlake won 43–29. “Since he was three years old, we’ve been talking about winning the state championship with him as my starting quarterback,” Dodge told a reporter after the game. “It was everything to me.”

A few weeks later, when Dodge was invited to speak at a conference near Washington, D.C., the family made a vacation out of it. They visited the White House, and during a public tour of the grounds, Secret Service agents arrived to whisk them away from the group. Minutes later, they were being ushered into the Oval Office. As Riley walked in, President George W. Bush extended his hand: “So you’re the kid who threw up.”

Dodge planned to stay at Southlake. Why would he leave? The program was humming, and Riley’s senior year was about to begin. It was everything a high school coach could want: dominate, rinse, repeat. In 2006 Dodge was named Southlake’s “Citizen of the Year.” And then, right before the ’06 state championship, UNT came calling.

The Mean Green offered to put Dodge in charge, and he couldn’t turn down a chance to coach Division I college football. He wouldn’t even have to move: Dodge could commute thirty miles to Denton while Riley and Molly finished high school at Southlake. Still, Dodge agonized over the decision. Breaking the news to his team was one of the hardest moments of his life. He had built a family in that field house, and this job offer had suddenly brought him back to his teenage years in Port Arthur, leaving one family behind to start over with another.

Dodge brought his offensive and defensive coordinators from Southlake to North Texas, wanting to reward their loyalty. But loyalty is no substitute for experience, and college teams picked apart the Mean Green and their high school coaching staff. Dodge lost his first game at North Texas to Oklahoma 79–10. The team won two games that season, and Dodge seemed outmatched by the college game. He didn’t have the same control over the program that he’d had at the high school level. It was a business, not a family, and he wasn’t experienced enough as a college coach to get his teams to play like brothers. “When you go through a window of success where you lose one time, by one point, in five years and then you flip that over,” he said, “there’s no doubt your confidence is a little bit shot. There’s some self-doubt that creeps in.”

Meanwhile, Riley had become one of the top recruits in the state, as much a threat scrambling as he was throwing the ball. He was driving home one day when UT offensive coordinator Greg Davis called to offer him a scholarship. Riley pulled over to the side of the road and accepted on the spot.

The commitment was just as much to Neptune as it was to the Longhorns. Riley wanted his grandfather to be able to watch him play at every Texas home game. But between Riley’s junior and senior seasons, Neptune had a stroke that rendered the left side of his body paralyzed, and when he got out of the hospital, the family moved him to the Dallas–Fort Worth area, where they could better take care of him.

Suddenly, the calculus of Riley’s college decision changed. If he went to Texas, his grandfather would never see him play; neither would his dad, who would be coaching in Denton. Dodge begged his son not to change his mind—no football star in his right mind would pick North Texas over UT—but Riley couldn’t be swayed. He recommitted to North Texas, to once again play for his dad, and to this day he remains the highest-ranked recruit in Mean Green history. When Riley was presented with the choice between family and football, he picked family.

He doesn’t regret the decision, but his parents wish they had done more to assure Riley that he could have gone to Austin without tearing the family apart. “If I had to [change anything], that’d be my one thing,” Elizabeth said. “That’d be it, in my entire life.”

Riley earned the starting job at North Texas, and by his sophomore year, he was playing well. Neptune made it to a game, watching from his wheelchair in the upper deck. But the Mean Green weren’t winning. During Dodge’s fourth year as head coach, after another 1–6 start, the athletic director called him to his office, and Dodge knew he was finished.

The next year, in 2011, Dodge coached quarterbacks at the University of Pittsburgh. It was the first time he’d ever lived outside Texas, and the first time he’d ever felt homesick. After one season, he and Elizabeth decided to return. That’s how Dodge wound up coaching in Marble Falls, a town about an hour’s drive northwest of Austin whose high school team hadn’t scored a point in its last four games before Dodge took over. In Dodge’s first four outings with the Mustangs, they averaged more than fifty points. Then, in 2014, Dodge’s phone rang. It was the superintendent from Westlake. “How would you feel about coming home?” she asked.

Westlake organized a press conference to announce Dodge’s hiring. After he took the job, he called Scott Norman, one of Neptune’s old players, and asked him to get in touch with every living Chaparral team captain. They formed the Captain’s Club, a group of almost fifty former Westlake players who meet with Dodge twice a year.

In 2018 Dodge considered leaving. Southlake wanted him back, but he didn’t pursue the opportunity because he loved working at Westlake. Plus, he still hadn’t won state with the Chaps. After Dodge made his decision, Riley called Bob Ledbetter, who’d retired as Southlake’s athletic director but who remained influential at the school. “What do you think about me throwing my hat in the ring?” Riley asked. At first, Ledbetter thought he was inquiring about a coordinator job. Riley had a sterling résumé, with assistant coaching stints at UT and Texas A&M—where one of his duties had been rousting Johnny Manziel out of bed—but Riley hadn’t even turned thirty, and he’d never been a head coach. Ledbetter said he’d consider it and would express Riley’s interest to Southlake. “I know one thing,” Ledbetter recalled thinking. “I can’t go wrong with another Dodge in that position.”

All week leading up to last season’s state championship, reporters asked Dodge and Riley how it would feel to look across the field at each other during the game. “I don’t think I’m gonna feel anything because I’ve never looked across at the other head coach and thought anything,” Dodge said. But game planning? “Oh, that was a pain in the ass,” Riley recalled.

Preparing for a football game is all about exposing your opponent’s weaknesses while masking your own. But these rivals had nothing to hide from each other. All season long, father and son had talked on the phone, revealing locker-room secrets most coaches would never dare share. They sent each other game tape and exchanged notes. Both teams ran essentially the same plays, down to using some of the same hand signals. So, with one week to practice, before the most important game of the season, each team had to change just about everything.

On game day, when the Chaps took the field, Riley’s son Tate stood near the end zone in a green Southlake jersey bearing his dad’s number 11. On his way to the sideline, Dodge stopped to hug Tate and take a picture with him before the coach put on his headset and snapped into action. Early in the contest, Southlake marched down the field like nobody had all year against Westlake. Dodge found himself doing exactly what he’d told reporters he wouldn’t—he glanced across the field at Riley and felt proud. He was looking at one helluva football coach. “There you go, boy,” he thought.

He glanced across the field at Riley and felt proud. He was looking at one helluva football coach.

The score stayed close until the second half, when Southlake threw two costly interceptions that allowed the Chaps to extend their lead en route to a 52–34 victory. After the final whistle, Dodge and Riley hugged at midfield. “I told him I loved him,” Dodge said. “I told him he should be very proud of his football team, and I told him, ‘I’ll see you in five days, at Christmas.’ ”

Only it was mid-January. For the rest of the Christian world, the holiday had come and gone. But for a football family tied up in state title runs at the end of a pandemic-postponed season, Christmas had been put on hold. And so, less than a week after losing state against his dad, Riley drove his family to his parents’ house in Horseshoe Bay, 42 miles northwest of Austin. Ask Dodge and Elizabeth, and they’ll say that except for the date, it was a perfect Christmas, with barely any football talk. Ask Riley, and he’ll say that the defeat still burned while he sat by the tree unwrapping presents.

If things had gone according to plan, Dodge would have already retired and last season’s Dodge Bowl would never have happened. When he took the Westlake job, in 2014, he and Elizabeth decided that he’d coach for six years, guiding one group of players from seventh grade, where the district middle school team runs Dodge’s system, through their senior year with the Chaparrals.

For a while, everything seemed to be falling into place. In year six, 2019, Westlake won its first state championship since 1996. Dodge could walk away with one last title to his name. Elizabeth helped talk him out of it. She taught fifth grade less than a mile from Westlake High, and when she watched the underclassmen on that 2019 team, she remembered those boys from her classroom. They had been more competitive than any group she’d ever taught, and they’d just about run her over every time she dismissed them for recess. She told Dodge it might be worth sticking around for that group. He was already starting to come to the same conclusion. “There’s still some meat on the bone,” he said, and six years became eight.

Next year, then. Next year they’ll relax. Dodge feels he has accomplished what he set out to at Westlake and now it’s time for a new generation to take over. Next fall, he’ll watch football from the bleachers on Friday nights. Some weeks he’ll make the drive to Southlake for Riley’s games. Others he’ll stay home and root for the Chaps.

He’s young enough to keep coaching, and he’s not shutting the door on a comeback. “If an opportunity comes about that I’m interested in, I’ll look into it,” he said. For now, though, Dodge’s retirement plans include gathering all his greatest quarterbacks—Chase Daniel, Sam Ehlinger, Cade Klubnik, Greg McElroy, and Riley—for a round of golf. Maybe he’ll go to Clemson to see Klubnik play or visit Indianapolis to watch Ehlinger in the NFL. This spring, Dodge will host about forty old Jefferson teammates for a crawfish boil, the former Yellow Jackets reminiscing over the Cajun food they grew up with. His father died of leukemia in 2010, but his mother, now 83, lives in Houston, and he wants to see her as much as he can.

But first, Dodge has one final playoff run to orchestrate. During the regular season, Westlake went a perfect 10–0 and won its district championship. So did Riley’s undefeated Dragons. Both teams begin their postseason campaigns Friday night, with Westlake facing the Hippos of Hutto High School, from about 30 miles northeast of Austin, and Southlake taking on the North Crowley Panthers, from Fort Worth. (To bring things full circle, Dodge first interviewed for a head coaching position in the early 1990s, when the 27-year-old coach met the Hutto superintendent at a Wag-A-Bag convenience store.)

This fall, though, due to the size of the other schools that qualified, Westlake and Southlake Carroll will be slotted into separate playoff divisions and there will be no Dodge Bowl II. Instead, Dodge has a chance to end his career on an even higher note: if both teams reach their respective title games (as they are both favored to do), Southlake will kick off its division championship on the afternoon of Saturday, December 18, at AT&T Stadium, in Arlington. Later that day, Westlake will take the same field for their chance at a ring as soon as the Dragons—hopefully—

finish hoisting their trophy. “That would be one of the best days of my life,” said Dodge’s daughter, and Riley’s sister, Molly Kuenstler. Then, a week later, the whole family will gather in Horseshoe Bay for Christmas—at a normal time this year, and hopefully with twice as much celebration.

One Thursday this fall, during Southlake’s bye week, Elizabeth started driving north on I-35. She pulled over to meet Riley’s wife, Alexis, at a Hilton in Waco, about halfway between their two homes. In the parking lot, Tate climbed out of Alexis’s car and into his grandmother’s back seat—much like the handoffs Elizabeth and her father used to do when Riley was a boy. Now Elizabeth turned the car around and drove back toward Westlake with Tate. The Chaps played later that night, and Tate ran along the sideline in Westlake’s red, white, and blue.

He was the ball boy. He loved it.

Joe Levin is a writer based in Austin. He was once the top-ranked amateur competitive eater in Texas.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Dodge Ball.” Subscribe today.