Come gather ’round, readers, and I’ll tell ye a tale

’Bout a clown ’neath the water who swam like a whale

A rubber face, pointy eyebrows, and pupils askew

A red nose and smile that seemed to say, “You’ll float too!”

This jester was playful and silly and wild

Definitely not at all something that will traumatize a child

San Marcos’s late, great amusement park Aquarena Springs was and remains famous for its many weird attractions. The mid-century tourist mecca at the headwaters of the San Marcos River boasted what it deemed the world’s only submarine theater, where underwater ballerinas called the Aquamaids performed to sold-out crowds several times a day. The shows made a splash with not only local but national audiences; when one of the Aquamaids got married in the theater in 1954, Life magazine dedicated a two-page photo spread to it, including the detail that the bride had sewn little lead balls into the hem of her wedding gown to maintain decency underwater. Another Aquarena icon, Ralph the Swimming Pig, who Molly Ivins once deemed “the Greg Louganis of Porkerdom,” was such a cultural phenomenon that he would eventually get his own feature-length documentary. From the time the park opened, in 1950, to today—a quarter century after its 1996 closure—there have been news articles, photography collections, parades, works of art, museum exhibits, and more dedicated to one of Texas’s kitschiest slices of history.

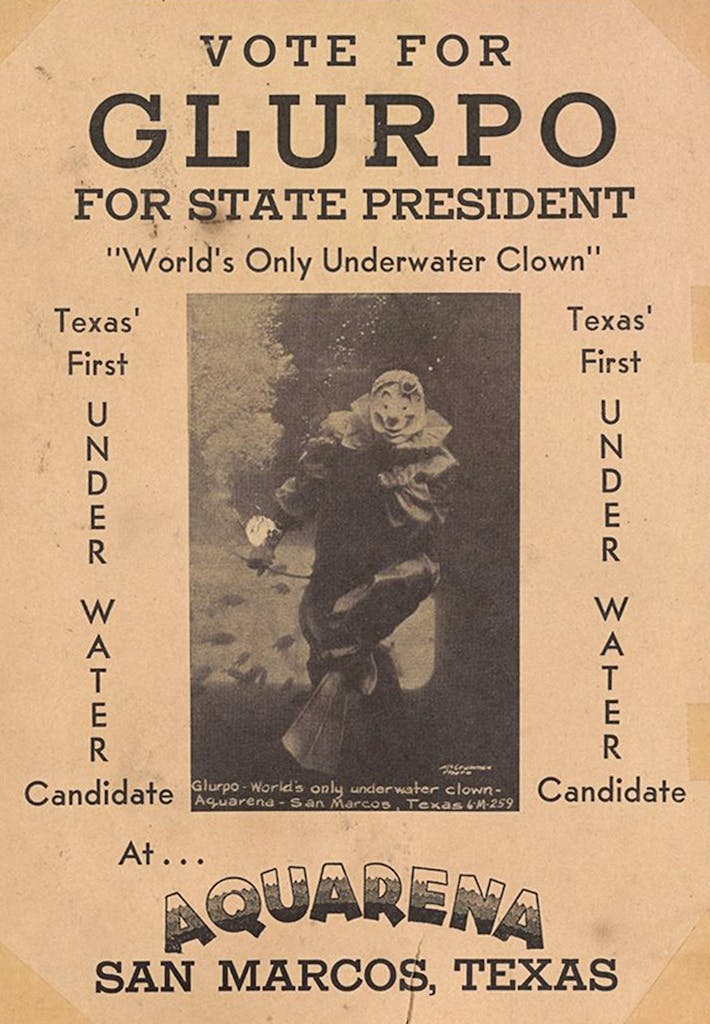

But this waterlogged wonderland was also the birthplace of an elusive creature whose story has more or less washed away with time, though his image occasionally pops up in the darker corners of the internet. That creature is Glurpo, the world’s first (and hopefully only) underwater clown.

Glurpo’s precise birth date is unknown, but he showed up in San Marcos in the early fifties as an assistant and comic foil to the glamorous, mermaid-like Aquamaids. As the ’maids danced through Spring Lake, the dammed-up body of water at the head of the San Marcos River, Glurpo served the crucial purpose of holding onto the hose from the tank of compressed air that allowed the ladies, ultimately still bound by the laws of land-mammaldom, to breathe. “He kept a close eye on the lady,” says Bob Phillips, who performed as Glurpo during the sixties, of the character’s assigned role. “As she gets through doing her ballet, after a minute and a half, you look for her hand, and when she opens up her thumb you have to put the air hose in her hand right then. You have to be right there to do it, because she really is out of breath at that time.”

The aquatic jester’s exact origins are also a little mysterious. Perhaps the idea for Glurpo came to Aquarena Springs’s owner and developer, Paul Rogers, in a dream. Maybe he and Glurpo formed their partnership on a desolate rural crossroads, like Robert Johnson and the devil. Or maybe Glurpo always lived underneath the springs—like the clown Pennywise does under Derry, Maine—and Rogers merely built the park to house him.

According to Maggie Younger, 91, who helped develop the show with Rogers and her then-husband Don Russell, Glurpo was created because “it seemed like clowns would be an interesting and entertaining element to enhance the underwater ballets.” Rogers had poached the Russells from Florida’s Weeki Watchee Springs resort to manage Aquarena. At the time, clowns were popular and not yet terrifying to children, and Glurpo was one of the many marketing tools Rogers could use to set his land-locked water show apart from its seaside counterpart. (He also built the submarine theater for this reason, since all the other water shows at the time were performed in above-ground tanks.)

Glurpo was your typical Bozo—a white face, over-arched eyebrows, cartoonish lips, a bulbous red nose, and a big, silly clown suit—but adapted for a soggier setting. His suit was made of a light nylon fabric that would move better underwater, and since swimmers couldn’t exactly sport clown makeup, Glurpo’s face was a rubber mask (with a tiny cowboy hat at the top—this was Texas, after all). To modern eyes, this only makes the clown’s flesh more lifeless and upsetting, but young baby boomers at the time were unbothered. “It wasn’t scary,” recalls Shirley Rogers, Paul Rogers’s daughter. She performed in the fifties as both an Aquamaid and, when audiences were large enough to require more clowns than there were male employees, a clown called Glurpette. “Kids loved it.” (It would be decades before John “the Killer Clown” Wayne Gacy and Stephen King’s It popularized the idea that clowns are scary. )

San Marcos’s maritime merrymaker had two particularly popular acts. One involved a camera and a framed mirror that allowed Glurpo to “take photographs” of kids picked out from the audience. Then there was the underwater pipe, from which the various Glurpos (or Glurpettes, or Bublios, which was the name of Glurpo’s occasional sidekick) would take a puff, then blow “smoke,” which was in fact condensed milk powder that had been stuffed into the pipe on land. “People were really astounded by that,” recalls Phillips. “They thought we were actually smoking underwater.” (Maggie Younger says her late husband Don Russell “deserves a great deal of credit for coming up with these ideas and testing them out himself.”)

Glurpo got his fair share of attention in the early days. When Popular Mechanics wrote about Aquarena Springs in June 1952, the clown was featured on the cover. A year later, one of the Glurpos (or, rather, one of the many actors who played him) flew to Hollywood to perform on the television program You Asked for It. “Glurpo intends to really wow his public on the TV program as he presents his unique routines,” Don Russell told a local newspaper. “Despite the fact that pretty Aquamaids are the main attraction of Aquarena’s underwater stage show, Glurpo boasts that he can not only do everything that the girls do, but also can show the fish and diving ducks a few tricks.” Glurpo’s cresting popularity even inspired the jovial jester to seek elected office. He ran for president of the San Marcos Junior Chamber of Commerce and then, in what might’ve been a bit of a reach even if the post weren’t fictitious, for president of the entire state.

But the tide would eventually turn, and Glurpo would have to adapt for new audiences. The first thing to go was, thankfully, the rubber mask. By the time Phillips took on the role in the mid-sixties, Glurpo’s clownishness was manifested only in his antics and silly suits. Later that decade, after Rogers died, in 1965, and the new owners added a volcano set piece, the show was redesigned to incorporate a Polynesian theme. “That’s when Glurpo the clown turned into Glurpo the witch doctor,” recalls Phillips. “He was still doing all the same things he always did, but we would wear a wig with plastic hair, a necklace, sometimes a bracelet, and we’d have a grass skirt on.” Younger says the changes were an effort to “keep things current.”

At some point the underwater show was once again redesigned, this time to depict historical events that had happened at the springs centuries before. The characters were Anglo settlers and Indigenous groups, and none of them, thank God, appear to have been named Glurpo. It’s not clear exactly when the wet jester faded away as mysteriously as he arrived—possibly in the eighties. Texas State University bought Aquarena Springs in 1994, and by 1996 it had become an environmental research and education facility. The underwater shows are long gone, but you can take a glass-bottom-boat tour. Glurpo exists only in old photographs, a handful of documents at the Texas State University archives, and my own personal nightmares. But perhaps he’s still out there, underneath us, resting in the frigid waters of the Edwards Aquifer just below San Marcos Springs. He smokes. He waits. And he whispers, “Don’t you want Glurpo to take your picture, little girl?”

This article appeared in the October 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Water You Afraid Of?”. This story originally published online on June 24, 2021. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- San Marcos