The plan seemed preposterous. John F. Kennedy was just 43 years old, and he’d been president of the United States for just four months—a rough four months. So far, his attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro had ended in quick and utter disaster at the Bay of Pigs, and the Soviet Union had beaten the U.S. to outer space, launching cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into orbit and bringing him home onto the Russian steppe. Now here was Kennedy, on the afternoon of May 25, 1961, in front of a joint session of Congress, offering up what his national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, had referred to as a “grandstand play.”

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth,” Kennedy said.

Congress greeted Kennedy’s cri de coeur with a smattering of applause. The president’s longtime speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, thought Kennedy sensed that “the audience was skeptical if not hostile.” A Gallup poll taken a week before the speech found that only 33 percent of Americans thought the nation should spend an estimated $40 billion to land a man on the moon. (The final bill ended up being $25 billion allocated over the course of a decade, about $180 billion in today’s dollars.)

Fiscal conservatives fumed. “We’re going to go broke with this nonsense!” remarked the president’s own father, former Securities and Exchange Commission chairman Joseph Kennedy. Scientists thought Kennedy’s proposed time span was fanciful. The Austrian theoretical physicist Hans Thirring told U.S. News and World Report, “I am quite sure it will not be done within the next 10 years, and I think it very likely not to happen within the next 30 years or 40 years.” And social reformers would come to see the Apollo program as a drain on needed resources. Whitney Young, president of the National Urban League, noted that America could “lift every poor person in the country above the official poverty standard” for a fraction of the cost of putting two men on the moon.

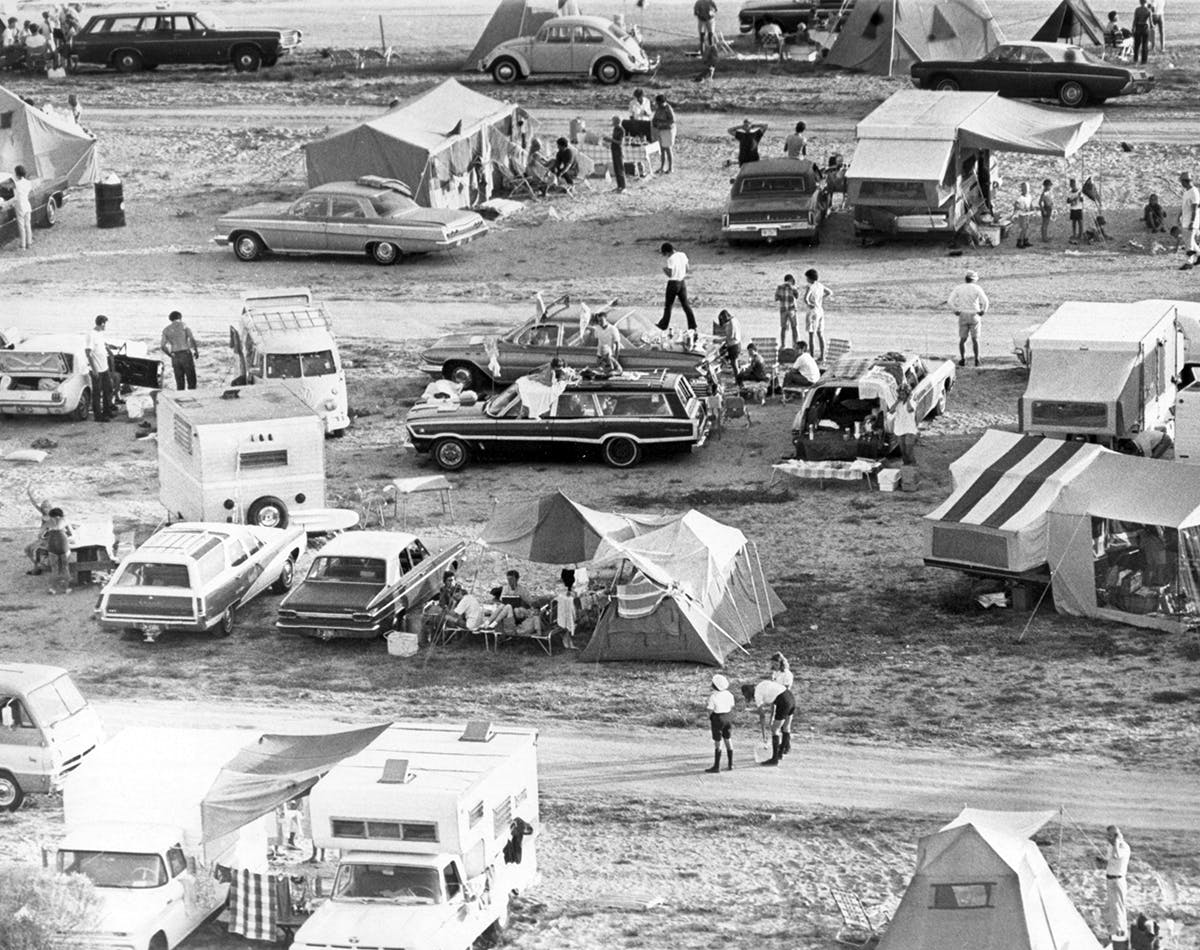

But on July 16, 1969, five and a half months before the end of the decade, a million people packed the beaches and highways of the Atlantic coast of Central Florida to watch the launch of Apollo 11. That morning, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins had woken up long before dawn and eaten the traditional NASA pre-mission breakfast of steak and eggs. As 9:32 a.m. approached, the three astronauts were sitting in their cramped command module atop a 363-foot, three-stage Saturn V rocket, going through their final preparations before countdown. Television viewers in 33 different countries watched as the Saturn V’s five engines reached their maximum thrust of 7.6 million pounds, lurching the spaceship into the air. For the next four days, the world kept following the mission’s progress as the crew flew 230,000 miles, entered the moon’s orbit, and finally touched down on the dusty lunar surface. “Houston, Tranquility Base here,” Armstrong reported back to Earth. “The Eagle has landed.”

Apollo 11 was immediately celebrated as a signal human achievement. Greeting Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins after they returned to Earth, President Richard Nixon said, “This is the greatest week in the history of the world since the Creation!” And in the decades since, the moon landing has only grown in reputation. NASA has called it humanity’s “single greatest technological achievement of all time,” and polling has shown a steady increase in the public’s belief that the space program was worth its high cost. Pop culture touchstones like The Right Stuff and Apollo 13 have celebrated the courage and resourcefulness of the original astronauts and the genius of the engineers and scientists who powered them into the heavens. Watch oversaturated 1960s footage of one of those mighty Saturn V rockets erupting off the ground and try not to swoon.

But as the moon landing’s fiftieth anniversary nears, new books and documentaries have arrived to remind us that our great American space epic was not, in fact, a frictionless succession of missions accomplished and ticker-tape parades. Even the most hagiographic offerings have moments that serve as correctives to our rose-tinted public memory.

Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11, by the Dallas writer James Donovan, is a largely familiar tale, a greatest-hits retelling of the Space Age from Sputnik to the moon landing. Donovan thrills at the celebrity of the Mercury Seven; mourns the deaths of Apollo 1 crew Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee; and, in the book’s best section, delivers a bravura ticktock of Apollo 11, with the Mission Control pencil pushers watching anxiously through thick clouds of cigarette smoke as Armstrong, a flyboy with the composure of a Zen monk, improvises a landing on the lunar surface before offering the world his inscrutable “One small step for man” koan.

But Shoot for the Moon isn’t all hero worship. Throughout the book, Donovan sprinkles in reminders that the public’s ambivalence about the quest to put astronauts on the moon continued long after Kennedy’s speech to Congress. Four years later, in 1965, Gallup found that only 39 percent of Americans thought the U.S. should do everything possible to beat the Soviet Union to the moon. Dwight Eisenhower had dismissed the need for a robust manned spaceflight program in the fifties, and he spent his post-presidency grumbling about the Apollo program, calling it “a mad effort to win a stunt race.” As Douglas Brinkley’s new history, American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race, makes clear, Eisenhower was far from alone.

Brinkley, a Rice University professor, focuses on the birth of the moon shot, taking us back a century earlier to show its roots in fantasy. French novelist Jules Verne imagined, in 1865, that the first lunar mission would involve three American astronauts launched from Florida, and American rocket innovator Robert Goddard announced, in 1920, that he had received applications from nine men who wanted to ride one of his ships to the moon. But Brinkley also notes that making a serious attempt to reach the moon was far from inevitable.

During the presidential campaign, Kennedy had hammered the Eisenhower administration for falling behind the Soviet Union in the space race, but in his early months in office, “Kennedy had adopted much the same cautious position toward space as his predecessor,” Brinkley writes. “Rather than focusing on headline-grabbing space launches, Kennedy was looking elsewhere for measurable accomplishment.”

Even after issuing his moon shot challenge, the young president expressed doubts and offered inconsistent rationales for why it was worth it. In his famous 1962 speech at Rice University, Kennedy rallied a crowd of 40,000 by promising that “new hopes for knowledge and peace” would come from exploring the moon and beyond. Two months later, in a private conversation with NASA administrator James Webb, the president declared himself “not that interested in space” and said that “the only justification” for the Apollo program’s lavish expenditures was “to beat [the Soviets].”

Then Kennedy seemed to waffle on the idea that the moon shot was a geopolitical competition. In September 1963 he proposed in a speech to the UN General Assembly that the U.S. and Soviet Union join together for a binational moon mission. When that proposal led nowhere, the president once more adopted a hawkish pose. On the afternoon of November 22, 1963, he was scheduled to discuss the Apollo program with the Dallas Citizens Council and tell them that “the United States of America has no intent of finishing second in space.”

Brinkley argues that Kennedy’s death ensured that the moon shot would have enough funding to meet its before-the-decade-is-out deadline. Delaying or canceling the program became politically untenable. “From 1964 to 1969,” Brinkley writes, “whenever Congress considered gutting the Apollo programs, [President] Johnson evoked the martyred JFK with don’t-you-dare political mastery.”

When the Apollo 11 crew landed safely back on Earth, the idea that the mission was only the start of the Space Age was widely held. In just over a decade, NASA had built three different generations of spaceships, blasted humans into orbit, sent astronauts outside their vehicles to “walk” in the void of space, and finally orchestrated the dizzying spectacle of the moon landing. The Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk had spurred decades of innovations that had forever changed the nature of war, travel, and trade on planet Earth. The space program seemed to offer the possibility of similarly radical results.

“I thought at the time it was the beginning of something,” says the former Mission Control technician Poppy Northcutt during the close of Chasing the Moon, director Robert Stone’s gorgeous, often bittersweet documentary on the space race, which premieres on PBS’s American Experience in early July. “I thought it was the beginning of moving out to other planets.”

Instead, in January 1970, NASA announced it would be shrinking its workforce by 50,000 over the next eighteen months. The agency’s budget, which reached a high of 4.4 percent of federal spending in 1966, dipped under 1 percent by 1975 and is now half a percent of the total. Over the past three decades, presidents George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama have all announced bold goals for human space exploration, with planned return trips to the moon, landings on asteroids, and voyages to Mars. None of these ambitions have come anywhere close to being realized. This past March, Vice President Mike Pence declared that NASA would send astronauts back to the moon by the end of 2024 “by any means necessary.” Don’t bet on it. Since the retirement of the space shuttle, in 2011, the United States hasn’t even had the capacity to launch humans into orbit, much less embark on a far more difficult and costly moon mission.

The pronouncements of private space moguls have been no more reliable. SpaceX founder Elon Musk said in 2017 that he would land humans on Mars and lay the foundation for a colony there in 2024, but the spaceship that would actually take those first settlers there is still a far-off concept. SpaceX was slated to begin ferrying astronauts to the International Space Station in 2015 as part of a NASA contract. It has yet to launch its first manned mission. Virgin Galactic, founded by the British billionaire Richard Branson, began selling $200,000 tickets to space in 2004. In the fifteen years since, the company has flown a grand total of zero customers, and four people have died during testing. In the epilogue of Shoot for the Moon, Donovan asserts, “A new spirit of space exploration is in the air,” but if there is a new spirit, it’s mostly wishful thinking. The astrophysicist and television host Neil deGrasse Tyson offers a more believable assessment of the state of manned space exploration in his 2012 book Space Chronicles. “Unless we have a reprise of the geopolitical circumstances that dislodged $200 billion for space travel from taxpayers’ wallets in the 1960s,” Tyson writes, “I will remain unconvinced that we will ever send Homo sapiens anywhere beyond low Earth orbit.”

So was Eisenhower right? Was Apollo a stunt? Did all those billions give us the world’s greatest photo op—Neil, Buzz, and an American flag on the surface of the moon—a propaganda victory over the Russians, and nothing else?

As a kickoff to a new Age of Exploration, Apollo was certainly a dud. No human being has left low Earth orbit since 1972, much less set foot on another celestial body.

Apollo defenders point to scientific and technological discoveries to justify the program. As Brinkley writes in American Moonshot, Apollo “teed up the technology-based economy the United States enjoys today,” leading to innovations in everything from computing to lightweight materials and meteorological forecasting. But these were all spin-off technologies that could have been developed for far less than $180 billion. The key engineering feats that powered the moon mission, the Saturn V rocket, in particular, did not spur the creation of bigger and better successors. In Space Chronicles, Tyson notes that “unlike . . . the first airplane or the first desktop computer—artifacts that make us all chuckle when we see them today—the first rocket to the Moon, the Saturn V, elicits awe, even reverence.” The last of those rockets, lying inert at a few museums, including Houston’s Johnson Space Center, stand like Gothic cathedrals. We stare and wonder how a culture ever marshaled the time, resources, and expertise to create something so intricate and grand.

Still, Apollo has had psychic benefits that are hard to quantify. It is now our most potent national myth. The word “moon shot” has come to signify a go-for-broke effort to do the impossible. The phrase “If we can put a man on the moon, then—” starts many sentences asserting that seemingly intractable problems may not, in fact, be so intractable. And, unlike the Manhattan Project, a grand American project that resulted in the prospect of nuclear annihilation, Apollo 11 was the realization of an ancient and benign dream.

After returning from space, a number of astronauts have talked about how the experience shifted their perspective on Earth, a phenomenon called the overview effect. Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell famously said, “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it.”

NASA, too, has developed something of a global consciousness. The agency may be best known today for its unmanned exploration of the solar system and the Hubble Space Telescope’s photographs of distant galaxies and black holes, but NASA also closely monitors the earth. It was a NASA scientist, James Hansen, who spurred global awareness of climate change with his dramatic 1988 testimony to Congress, and the agency’s Earth Science division has used a global network of satellites to track our planet’s changing atmospheric conditions. Even now, under the direct control of a White House that has sought to undermine climate science, the agency remains clear-eyed. NASA’s website documents the warming of Earth’s oceans, the shrinking of our ice sheets, and the growing prevalence of extreme weather events. The agency has no doubt about the cause: “most of it is extremely likely (greater than 95 percent probability) to be the result of human activity since the mid-20th century.”

If the Apollo program’s great achievement was to demonstrate that with enough money, courage, and scientific know-how we can do what seems impossible, then perhaps its example can help us tackle the great challenge that NASA sees bearing down on our planet right now. This would, in fact, be in keeping with Apollo’s history.

Toward the end of Chasing the Moon, Stone shows archival footage of the Apollo 11 crew’s worldwide goodwill tour. The astronauts have suddenly become international heroes, and everywhere they go, adoring throngs greet them. At press conferences, reporters ask Armstrong and Aldrin how it felt to be there. They often struggle with the answer, but in Stone’s film, we watch the habitually taciturn Armstrong respond to one such question with poetry.

“As we looked up from the surface of the moon we could see above us the planet Earth, and it was very small, but it was very beautiful,” Armstrong says to the crowd of foreign reporters. “And it looked like an oasis in the heavens. And we thought it was very important, at that point, for us and men everywhere to save that planet, as a beautiful oasis that we together can enjoy, for all the future.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Space