My sister Jane and I grew up in North and West Texas. Not in scenic or artistic communities like Marfa or Alpine, but small cities like Wichita Falls, Abilene, and Midland, where wind rattled the windows and red dust seeped under the doors.

Daddy worked for an oil company that moved us every few years. Our family always lived in small, one-story houses called “ranchers” on the edge of town. There, in the sun-baked dirt of a new yard, Mother would plant a single, spindly tree that had to be staked down so it wouldn’t blow away. We never stayed in a house long enough for the tree to grow any bigger than a yardstick.

Outside, it was so flat and barren you could see for miles, but you probably didn’t want to. Life indoors held its own bleakness. Mornings, when we woke to hear Mother singing in the kitchen, Jane and I knew it would be a tolerable day. Other days, when Mother’s face twisted and she began to insistently pick at us for everything we did wrong, we learned to make ourselves as small and unobtrusive as we could. But shrinking didn’t help. Mother wouldn’t leave us alone until we cried and apologized for being such awful children. Daddy, eyes downcast, never interfered. That was because he didn’t like children, Mother said. He hadn’t really wanted them. Well, us.

Jane and I learned to ignore our family’s unhappiness. We read. We read constantly, hauling armfuls of books home from the library, losing ourselves, taking on other skins and lives, skipping across continents and centuries. We weren’t pint-size intellectuals; we were escape artists looking for a ticket to somewhere, anywhere else. We read biographies of our favorite royal family, the Tudors; stories about scrappy frontier girls and teen-girl detectives (who all seemed to have dead mothers); the Betsy-Tacy series about idyllic Midwestern childhoods; and comic romps like Life With Mother Superior and Cheaper by the Dozen. Give us a mouthy, subversive main character and we were in love, sharing favorite quotes with each other over and over, screeching with laughter.

Years later, I came across a story that haunted me about Mary Ann “Molly” Goodnight, the wife of the legendary Panhandle rancher. When Charles was gone for days and weeks at a time, she was so lonely she talked to her chickens. (In Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, frontier woman Clara Allen says: “I keep those hens to talk to me when I’m lonesome. I’ll only eat the ones who can’t make good conversation.”)

For my sister and me, two lonely and sad West Texas girls, we had books, and we had each other. So many things changed for both of us, but that never did.

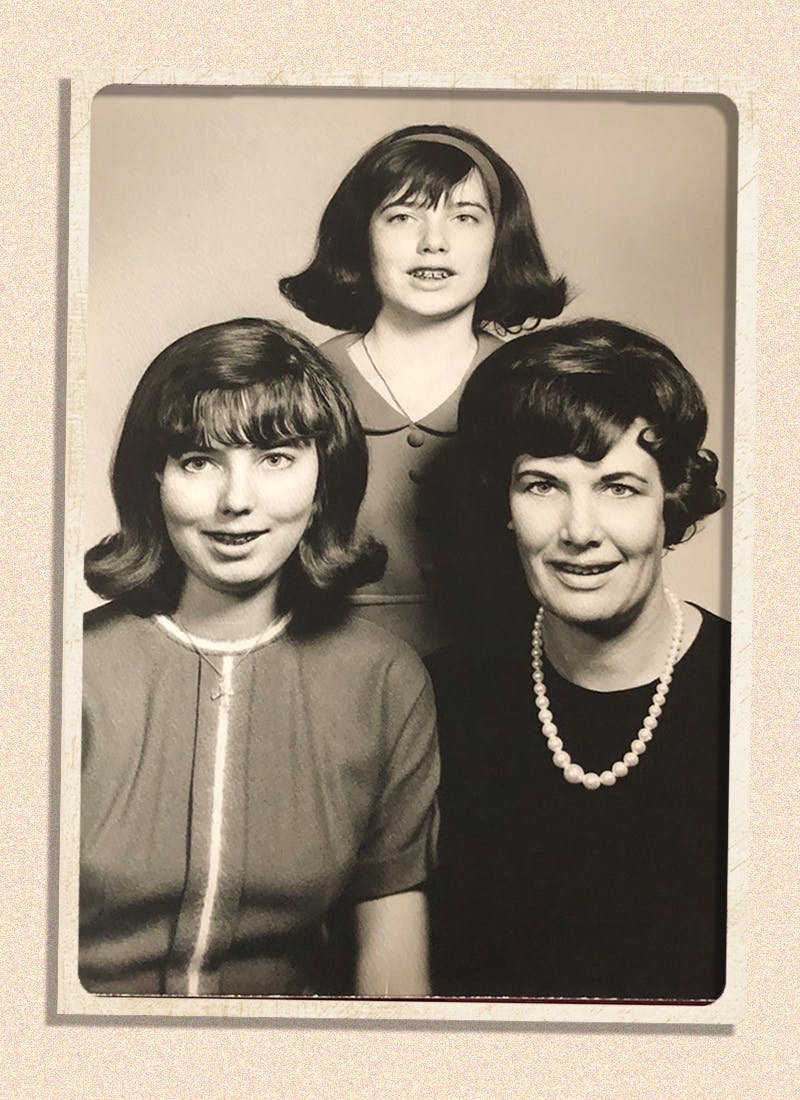

We read through blistering summers and gray winters, through our parents’ bitter disappointments and Mother’s blackest depressions. Jane, who was three years younger, insisted on reading the same books I did—which annoyed me. After all, she got to be the pretty daughter, with shiny dark hair and vivid blue eyes, while I was a grade-school train wreck, plump and buck-toothed, with smudged glasses that slipped down my nose. Obviously, I deserved to be the smart daughter. But no.

In my occasional moments of brutal self-assessment, I had to admit Jane was as smart as I was. Maybe smarter, which really killed me. God, life was unfair. Sometimes, I watched Oral Roberts on TV, squeezed my eyes shut, and prayed for Oral to cure me of having to wear glasses so I could be pretty, too. It didn’t work. Oral healed the lame and the halt, but he bailed on a ten-year-old with an astigmatism. No wonder I lost my faith.

Daddy worked as an accountant, which he never liked to talk about. He didn’t rise, he didn’t fall; he just worked steadily then came home and watched TV for hours into the night. Mother cooked and cleaned and took to her bed for days when depression overwhelmed her. Twice, she had to be hospitalized for a week or two.

Our parents were strikingly attractive, and they had a passionate attraction for each other. But over the years, sour disappointment settled in, something you could almost smell. She was a smart, mercurial woman married to a man without curiosity or much ambition. He was a man who valued calm and predictability wedded to a complicated, restive woman whose volatile moods scared all of us.

In 1965, we moved to Midland. A rich town, we heard, and we weren’t rich. In fact, we were barely clinging to middle class. Daddy once had a tooth pulled since it was cheaper than a filling, Mother told us. That was so Jane and I could get braces and music lessons, even though we weren’t loving sisters like our better-behaved cousins who sent us their hand-me-downs once a year.

On the drive to Midland, Mother sat in the backseat with Bouncer, our foul-tempered fox terrier. For years, Bouncer had often bitten Jane and me. Mother said we provoked him. This time, Bouncer bit Mother for the first time. She started sobbing. The other three of us stared straight ahead, silent. That was always the safest thing to do.

Once we got to Midland, Bouncer disappeared after a visit to the vet. We pretended not to notice. Jane announced she hated her first name and, in a new city, would go by her middle name, Ellen.

Ellen, now 12, was different from Jane. She gave up the violin, which her teacher in Abilene said she’d shown a rare genius for. She dyed her hair black, she wore darker colors, she reeked of strange perfumes. She ignored her schoolwork and got hauled into the principal’s office again and again.

Months passed. Ellen skipped school, she ran away from home, she became notorious around town. She drank and she smoked and she was “wild”—code for promiscuous in a religious, conservative town in the sixties. West Texans weren’t known for holding nuanced views of female behavior.

We were a respectable, conventional family who went to the Methodist church and Sunday school every week. We held hands, prayed before meals, and used good grammar. We might have had problems, but they were private, whispered about when the windows were closed and doors locked. Ellen, with her outrageous appearance and behavior, had blowtorched a massive hole in the front wall of our tidy rancher.

For me, though, all the noise and upheaval were mostly background. I was practiced at living in my own head, reading and daydreaming, removing myself from the unhappy world around me. In my mid-teens at a public high school, I was painfully introverted and lonely. My grades were good and my appearance improved with time, but so what? I was a social zero without boyfriends or prospects, which was how my family defined teen girl success. Worst of all, I developed a full-blown social phobia about speaking or performing in public. Like my sister, I was a mess. But I was a quiet mess.

Occasionally, I sneaked into Ellen’s room when she was gone and read her diaries—spiral notebooks filled with her slanted, intense scrawl. It was as if I were looking at something written by a stranger. Ellen had always been “high-strung,” as Mother said, overly sensitive and emotional. But now she was someone else, foreign to me.

Did she still seek comfort in books the way I did? I don’t know. During those dark, confusing days, Ellen and I rarely spoke; what would we have said? She was having sex at a very young age, and, three years older, I was pretty sure my virginity was the only thing going for me. Was she as appalled by me—her timid, boring sister—as I was by her? And what kind of pitiless, stone-hearted person feels “appalled” by her own sister?

Mother was frantic, always planning some intervention, some miracle cure. She and Daddy sent Ellen to therapists. They had her institutionalized briefly in a nearby state hospital. She was diagnosed and re-diagnosed. She was impulsive, hypersexual, and/or manic-depressive. Whatever the diagnosis, nothing changed. At fifteen, she dropped out of school. Months later, she knocked the top off her GED test. That intrigued the examiners, who gave her an intelligence test. Her IQ was in the low 160s.

“You know what I tell Ellen?” Amy, a social worker who was my sister’s longtime therapist and her great admirer, once said. “I tell her that with her brains and passions, she’ll either be a stunning success or a miserable failure when she grows up. Nothing in between.”

But, you know, adult life—real life, daily life, with its head colds and bills, its dirty laundry and to-do lists—usually wears down the most melodramatic predictions. Most of us don’t turn out to be extraordinary successes or failures; we trend to the mean, the great in-between. But Ellen never had any use for moderation.

After taking her GED, she went to a radio school in Dallas. She lost her Texas accent, learning to speak in precise, clipped syllables. She worked as a deejay in Midland, then in radio administration in El Paso. She married a lovely man, but that didn’t last long.

In our twenties, she and I were close again, swapping book recommendations and comparing family stories about our hapless parents, the way adult children do. She wrote me letters that were corrosively funny; she was one of the most wickedly comic writers I’ve ever known.

When we were together, we focused on what we had in common: unhappy childhoods with the same parents, books and more books, caustic humor, politics. We never talked about the obvious differences: I was married with two children. My husband and I were ambitious and educated. We were middle-class, homeowners. We fit into a world that Ellen didn’t. She lost jobs, struggled financially, dressed strangely in flowing dresses with billowing sleeves. She still drank heavily and lived recklessly.

Ellen fell in love again in the mid-eighties in Dallas. Bill was overbearing and made constant sexual references. He was bipolar, it turned out, and resisted medication. A relentless salesman, he talked up a series of businesses, including ads in toilet stalls, which he was especially keen on. When Bill’s ex-wife sued him for child support, the judge gave him two weeks to come up with $10,000 or go to jail. Instead of going to jail, Bill went to Israel.

Once there, he sent for Ellen. Since she wasn’t Jewish, they married by proxy, over the phone, so she could settle in Israel. Israel—a country that was more like a distant rumor than a real place when you’re from a family that lived in Texas and took vacations in Oklahoma. Mother sobbed over the phone, begging her not to go. But nobody ever stopped Ellen from doing anything she was intent on. She sold a few possessions and stored what was left in our garage.

I don’t remember saying good-bye before she left. She was my sister, and I loved her. But I had my own life and ambitions. I was writing for newspapers, magazines, and public television and radio in Dallas, and I had begun to write books, too. I was busy, overcommitted, with work and family. The truth was, Ellen embarrassed me and unsettled me. I didn’t know how to weather her turbulence and unpredictability. In more ways than I wanted to admit, her leaving was a relief to me.

Ellen lived in Israel for two decades, into the early years of the new millennium. She worked steadily as a proofreader for a patent attorney. She loved the new country and its people, taking on its beliefs and struggles like another skin. But she never converted to Judaism; by then, she was a passionate Russian Orthodox, spending any spare money on religious icons.

She visited the U.S. every couple of years. She had become a blonde, but her most striking feature was still her vivid blue eyes. Her appearance was more exotic, even though she wore the same long, flowing dresses she had for years. She had become another nationality, an expatriate, more comfortable at a distance of thousands of miles. It seemed easier to be herself in another country.

My son and I visited her and Bill in 1999, traveling around the tiny country in a rented van with them and another couple. We saw Jerusalem and the Dead Sea, Haifa and Masada, the antique and the modern. “Do you realize,” one of her colleagues asked me one day, “that your sister is the best-loved person in our office?” That remark was puzzling. When had Ellen ever fit in anywhere? Hearing it was as confusing as traveling thousands of miles to Ellen’s home in Beersheba and realizing that her part of Israel looked just like West Texas.

After Bill’s years on lithium, which managed his mood disorder, his kidneys failed. He died a few days later. Ellen was sick with grief, deeply depressed. She had lost her job and was desperate to find work. I assumed—we all assumed—she would come back to the U.S.

She didn’t. She moved to Poland in 2008.

Some of Ellen’s new friends, other widows on an Internet site, had assured her she could make a living teaching English in northern Poland. “It’s a lovely city,” Ellen told me. “Gdynia. It’s on the Baltic, close to Gdansk.”

“How can you move to Poland?” I asked her accusingly. “I thought you and I were going to grow old together.” But that wasn’t true. I was just saying it to make her feel guilty. I never really thought we’d grow old together. Our lives were too glaringly different. We had grown used to having an ocean between us.

Ellen had never taught before, but she loved it, tutoring younger students in coffeehouses and adults in their workplaces. She taught her students good grammar and carefully enunciated swear words, recommended books, worried about their lives and futures.

Even though she chose to live at a distance, I always knew Ellen loved me. When I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1995, she had come to Dallas to stay with us. She and I spent afternoons watching my favorite movies on TV. I was so exhausted by chemotherapy that I always fell asleep on the couch before the movie was over. When I woke up, she was sitting there, watching me to make sure I was all right.

But she usually didn’t show up. After Mother’s death, she wasn’t around to look for care facilities when Daddy developed dementia. Money was always a problem for her, but so was living a marginal life in another country. She couldn’t come to Daddy’s funeral because her passport had expired. She missed our daughter’s wedding because of immigration problems.

In 2012, she married an American she’d worked with in El Paso in the seventies. They wed in Kentucky, where he had lived for years. She returned to Poland alone, and for a year, they argued about where they would live. Finally, he joined her abroad. No one was ever more stubborn than Ellen.

In 2015, around the time our first grandchild was born, Ellen was diagnosed with stage IIIB breast cancer. She was furious about being ill and confined, and didn’t want me to come to visit. Instead, I sent her a wig, wool sweaters, hats, worried she wouldn’t be warm enough. Maybe warmth was the only thing I could offer her. She went through chemo, then surgery, then more chemo and radiation. She kept working.

In the fall of 2017, when we talked or emailed, she mentioned she was in pain. The pain moved around her body. She couldn’t really locate it. That winter, a few days before our second grandchild was born, Ellen went to the hospital with a broken leg. Doctors told her the cancer had metastasized to her bones and liver. Her life was contracting into pain and disease just as mine was expanding.

I flew to Poland with Maria, a cousin I’m close to. I almost didn’t recognize my sister. She was so much smaller, huddled in her bed in the apartment. Her hair was short and brownish and her eyes had faded to a dull gray-blue. But it was her face, shrunken and drawn, that shattered me. She looked exactly like our mother at the end.

Maria and I stayed there a week, walking the gray January streets close to the Baltic, bringing Ellen her favorite fish soup from across town. We sat in her small bedroom for hours as friends came and went. One told us the hospital had been amazed by how many visitors Ellen had had—friends, colleagues, students, acquaintances. “Do you know what her nickname is?” another said. “We call her Nokia because she loves to connect people so much.”

One night, I watched as she chatted with a group of friends, her head against the pillow. She talked about changes in Poland’s government, fears of Putin and Russian aggression, the outrages of the Trump presidency. She told of traveling to Romania, to Ukraine, even to Moldova (most recently notorious for being the world’s unhappiest country. Moldova! Who goes to Moldova?). I couldn’t stop watching her, my little sister, Oklahoma born, West Texas bred, the youngest member of a family that never went anywhere. She had no formal education, no credentials; all she had was an endless curiosity about the world and an openness to other people. In some ways, I was seeing her for the first time, understanding her better than I ever had before.

Over the next year, I emailed her drafts of a novel I was writing. Hurry, she kept pleading. Write faster. I also mailed her a package of books every month—novels and biographies, other nonfiction. She particularly loved Elizabeth Strout’s novels like Olive Kitteridge and Robert Caro’s volumes of LBJ’s biography, Paulette Jiles’s Enemy Women and News of the World. She carried a book with her everywhere, she said. When she read, the harsh world around her disappeared—as it always had for both of us.

I visited her again in July, then in November. Ellen was hobbling around by then, leaning on a single crutch. She and I went to restaurants and coffee shops, talking about our painful childhoods, the books we loved, our parents, our pasts, our lives, and now, death.

She told me again of the times she had been visited by the newly dead. Bill had appeared in their small apartment, raging about his death. Our mother and father had each come to her in vivid dreams. Another close friend had visited her during a difficult time. “You are tough as nails,” he had whispered to her, as he had in life. Nothing like this has ever happened to me, but I always believed in her other-world experiences.

We spoke about everything, large and small, except for what we had never talked about: why had she changed so dramatically in adolescence? Had she been sexually abused, as some of my friends have suggested? Why did I never ask her to explain? And why had she and I chosen lives so different they were almost a rebuke to each other? Or was choice just an illusion? “I don’t regret my life,” she said one day. It was an answer of sorts.

Ellen died December 18, 2018, four days after she taught her last class.

I got email after email, all from friends ravaged by grief. Several people told me she had changed their lives. “I could tell her anything,” one said. “She never judged me.” Students wrote how much they loved her and had learned from her. Her rare empathy and compassion were mentioned over and over.

We had been sisters for 65 years. We didn’t have an easy or simple relationship, but she was my sister and only sibling, my blood, my past. She knew my earliest stories, found humor in the same bleak landscapes, knew me in a way no one else ever will. When she died, I lost one of the great loves of my life and the greatest puzzle I’ll ever know.

When was the moment her fierce intelligence, her willfulness, her crazy impulsiveness, her endless empathy were extinguished, and why couldn’t I feel the change in the air when it happened? Will she come to me now, return for just a few minutes from all her travels, so we can finish the talks we never had?

“I can’t imagine the world without you in it,” I told her on our last visit. Or maybe I couldn’t imagine who I would be, the surviving sister, once she left me.

Ruth Pennebaker is an Austin-based novelist whose essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other publications.