Someone came up to me recently with some hot news. “Hey, did you hear about Jerry Rubin? He’s selling wallpaper on television.”

He had taken at face value an NBC Saturday Night parody of a commercial in which Rubin, the ex-yippie leader and Chicago Seven defendant, does a huckster spiel for a special line of sixties wallpaper, complete with peace, love, and protest motifs. It’s obviously a spoof, but no doubt many people believe it—partly, of course, because commercial advertising is not something you fool around with, but mostly because so many people want to believe that the radicals of the sixties have sold out. Surely those devout, committed, self-righteous children of the years of defiance have come to their senses at last and are out hawking insurance.

Well, Jerry Rubin for one isn’t. In fact he is promoting his new book, Growing (Up) at 37, a sequel to his earlier Do It!, which advocated, along with some things less lawful, not growing up. He is also reportedly trying to raise $2 million to start a weekly newspaper in Los Angeles. Others of the Chicago Seven have taken their diverse courses: Rennie Davis became a convert, a disciple of the adolescent Guru Maharaj Ji. Tom Hayden, the intellectual mentor of what used to be called the New Left, married actress Jane Fonda and ran, unsuccessfully, for the Senate in California this year. Abbie Hoffman is underground eluding a cocaine rap.

These were the headliners of the sixties, but in a sense their fate is only of marginal interest. The upheaval of the last decade was much more than the media adventures of a handful of interesting characters. Beneath the courtroom antics and the peace marches and the slogan chanting and draft card burning, profound changes were occurring in the United States and the world. At the cutting edge of that change was a group of young people who called into question the American Dream and rebelled against assumptions and goals taken for granted by previous generations.

Perhaps we can gain some insights into the sixties by revisiting a few of the people who spent those years on the front lines. These are people who seldom made headlines, whose names were known mostly to their friends and assorted police undercover agents, but who were nevertheless committed members of what they called the Movement. These were the people whom Time named collectively “Man of the Year” for 1967. “This is not just a new generation but a new kind of generation,” wrote the editors. “Today’s youth appear more deeply committed to the fundamental Western ethos—decency, tolerance, brotherhood—than almost any generation since the age of chivalry.”

Almost ten years later it is appropriate to look back and ask whether Time in its wisdom was right—or whether time in its wisdom has voided the high-flown rhetoric of that very different era. Certainly this so-called new generation left its imprint on history at a younger age than any other: it helped topple a president, end a war, revolutionize the campus, introduce drugs to the middle class, and raise questions in people’s minds about everything from sexual mores to whether their government lied to them. It all seemed so momentous at the time, so apocalyptic. Now, as we have gained at least a little distance from those frenetic days, we can start asking the larger questions. Such as: Did it make any difference? Did this generation indeed leave its mark on the world? Or, for that matter, did it even have any permanent impact on itself?

Well, who knows? Most of us who lived through it are still trying to sort it out for ourselves. I have no intention here of constructing some grandiose analytical overview of the sixties explosion. Instead I have tried to arrive at some tentative answers by preparing sketches of several of my friends who were Movement organizers: what they did then and what they’re up to now. It’s an arbitrary but rather homogeneous group. They are white, thirtyish, and come from moderately affluent family backgrounds. Most are native Texans and all were in the state during the middle and late sixties. All made substantial commitments to the Movement: they threw away their comfortable lifestyles and lived a marginal, even spartan, existence. Most worked with the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the organization which, before it succumbed to internal bickering and hardening of the ideological arteries, most nearly embodied the ideals of the American New Left.

Before I go on to tell you who these people were and are, I should first make clear who they were not. They were not peace-and-love hippies, though they shared with that group the new social and cultural preferences of the day. They were instead serious political radicals who had visions of a better world and dedicated themselves to building it—both in their own lives and in society at-large. Just as they were not flower children, they were likewise not cerebral ideologues, spouting Marxist rhetoric to telephone poles. For the most part the radicals, like the rest of their generation, grew long hair, experimented with drugs, attended love-ins, lived together out of wedlock, and indulged in rock music. But these things were not seen as ends in themselves; the radicals also discussed political theory, conducted seminars, planned demonstrations, and published underground newspapers. Hippies spoke of love; radicals spoke of love and power.

A second important negative: none of the people whom you are about to meet is black or brown. Although the New Left was inspired by and supportive of the activities of those minority groups, in the end it was almost exclusively the province of whites, and middle- to upper-class whites at that. Ethnic radicals were removed by substantially different circumstances; but that is a different story, and one I am less qualified to tell.

It is the people now between the ages of 28 and 32 who were most deeply caught up in the dynamics of the sixties. A recent New York Times survey by psychological specialists found that large numbers of people who grew up in the sixties are currently suffering a “generational malaise.” These psychologists report an increase of people in this age bracket committing suicide, becoming alcoholic, seeking psychiatric help, or turning to kooky cults. Movement activists may have been the worst hit, and I know many who underwent heavy periods of despair and depression.

But other studies are more hopeful. A Florida State sociologist sought out former civil rights activists to learn whether, as studies of former political radicals in Japan have consistently shown, they had become “slaves to materialism.” The people he tracked down “were still active politically and were still committed to institutional change.” They had neither dropped out of society nor gone corporate. This is also basically true of the men and women with whom I’ve talked. Most have mellowed and made their peace with society, but they have retained their Movement values, if not its rhetoric.

Judy Gitlin, Dennis Fitzgerald, and I all graduated from Houston’s Bellaire High School in 1963. Judy and I were acting partners in drama; Dennis was the wiry, curly-headed editor of the student newspaper who talked of writing the great American novel. Even then Bellaire was vaguely feeling the tremors of the advancing youthquake.

The three of us went off to the University of Texas to seek whatever one goes off to college to find, including, if it fit in, a formal education. It didn’t: none of us would finish school. Dennis and I shared an off-campus room our first semester; then he dropped out of school—it was still too early to talk of dropping out altogether—and left Austin for San Francisco. There he found the youth of the Bay Area in turmoil; that turmoil would soon erupt on the Berkeley campus into the Free Speech Movement led by Mario Savio. Word filtered back that Dennis had been arrested in a civil rights demonstration at a San Francisco hotel.

The campus Dennis had left behind was far from a hotbed of student activism. Fraternities and sororities continued to be a major social and political force on campus, and the Greek-dominated Representative party only a year earlier had lost its long grip on the UT student body presidency. A large majority of students were openly hostile to the small activist element, who agitated for civil rights and urged UT to take a leading part in the left-leaning (but, later we would learn, CIA-funded) National Students Association. Judy and her friends learned the words to freedom songs, located a small place called Viet Nam on a map, and joined a new organization called the SDS. Though they were 2000 miles apart, Dennis and Judy found their worlds changing together; they began to see themselves in the vanguard of a sociocultural revolution.

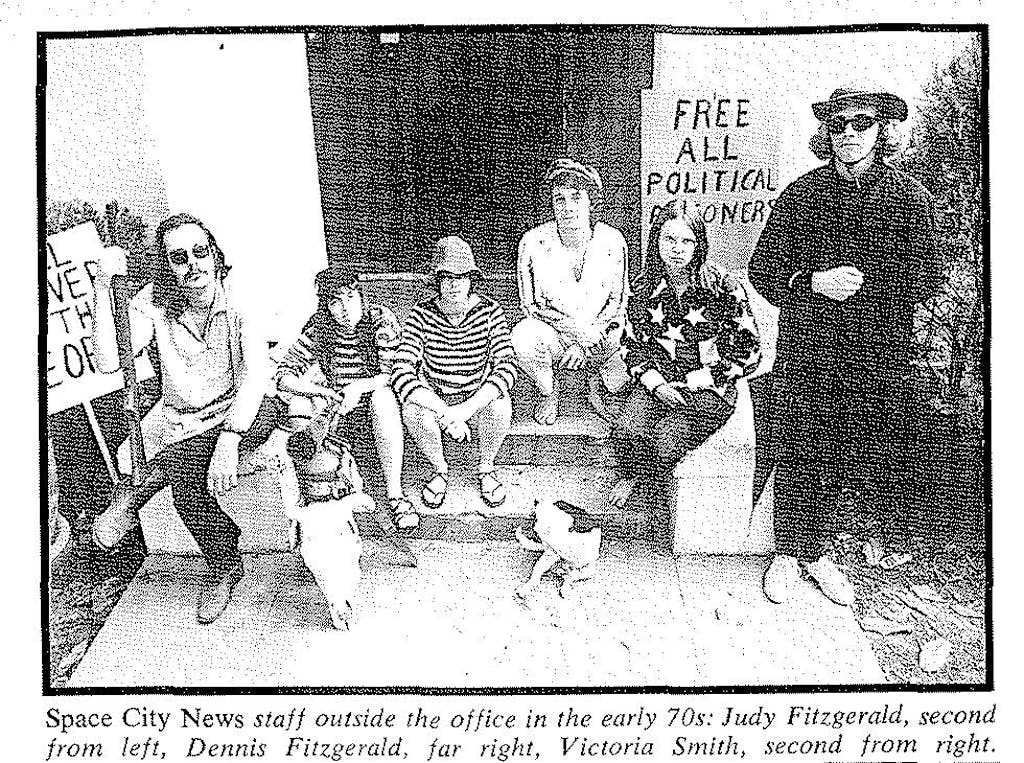

In the summer of 1965, Dennis returned to Texas. Several months later he and Judy got married. They even had a ceremony—something of an unusual event, since by that time most couples in the Austin counterculture just lived together. Dennis and Judy were two of the primary movers behind the Rag, Austin’s underground newspaper, and three years later, behind its Houston counterpart, Space City News.

Dennis was one of the most literate writers in the underground press; his work had clarity, originality, and solid analytical perspective. He also had a propensity to get beat up by cops and other hostile parties. He was bloodied by police during a demonstration against Spiro Agnew in January 1971, and once, while he was peddling Space City News on a Houston street corner, an unfriendly soul flashed a gun and then slugged him in the nose.

Weary of the urban struggle, Dennis and Judy joined a group of Texas radicals at a commune in rural Arkansas in 1972. “We didn’t have to shuffle with ideology,” recalls Judy, “just dig up the garden.”

Judy remembers the country experiment as “a blind leap of faith—everybody closed their eyes and jumped in.” She and Dennis viewed the move as a long-term commitment, not just a momentary idyll. “We were trying to recapture some kind of lost intensity,” says Dennis. They wanted to simplify their lives, to get closer to the earth, and to establish a stable community in the process. But it ended in failure. In practice it was hard to resolve such issues as individual commitment to the group and what the basic concept of the commune should be. People came and went, tensions developed, and, in one communard’s words, it became “a psychological pressure cooker.” For Dennis and Judy it was the end of innocence, the realization, as Dennis says, that “interdependence among friends wouldn’t work, that we were not as close as we thought. It’s freeing now, not having so many expectations of other people.”

Judy and Dennis and their six-year- old daughter Kelly are back in Houston now but they hope soon to return to a more rustic setting. (“I still want that rural experience,” says Dennis. “It feels good outdoors, doing things, with your hands.”) Judy is working at a bookstore and has been attending classes at the University of Houston. Dennis has returned to journalism, but with an ironic twist: he has just completed a stint as assistant city editor for the Houston Chronicle, which even by seventies standards can fairly be described as the establishment daily. Dennis stepped down from the editorial position because he wanted to do more writing. Dennis has no career ambitions at the Chronicle, though, and in fact he and Judy are currently considering a move to the Pacific Northwest, possibly even Canada.

“A good while ago I quit trying to reform the Chronicle,” he says. “Now I see newspapers—as an institution—as more pluralistic. They’re as good or bad as the people doing them. I’m not sure the editorial stance of a newspaper is so important in shaping public consciousness. The ownership sets the boundaries and tone, but it doesn’t say what facts go in on a daily basis.”

As a fifteen-year-old high school sophomore in Fort Worth, Gary Thiher was briefly infatuated with Barry Goldwater’s brand of Republican conservatism. Then he began to read Kerouac. Later in high school, he and a group of friends formed an iconoclastic organization they called the Dharma Bums Club, where “we’d sit around beating on bongo drums and reading dirty poetry.”

At the University of Texas Gary was a charter member of the Austin SDS chapter. He studied philosophy, history, and government, and in 1965 made a kamikaze run for president of the student body. The Thiher campaign gave a somnambulant student body the first notice of the Movement’s growing presence. Its tactics included a lively morality play performed on campus during class changes, a campaign song written and bellowed, by local folksinger John Clay (“We know he cannot win, ‘cause he’s advocatin’ sin”), and a platform that included hitherto unheard-of issues like student power and free birth control pills in the Health Center.

Gary was endorsed by the unlikely combination of the Young Democrats, the Young Republicans, and the Young Americans for Freedom: they were so intrigued by a candidate running on issues instead of grade-point average and fraternity affiliation that they accepted his then outrageous positions and style. And of course it was still early, before the escalation of the Viet Nam War, before the succession of riots in the urban ghettos. The Movement was still in its innocence and was not yet regarded as a dangerous adversary. To no one’s surprise, Gary did not win the election—he got 2448 votes, roughly 25 per cent—but his campaign set the tone for an Austin-style activism which would always incorporate an upbeat theatrical approach with its serious discussion of issues. Five years later SDS veteran Jeff Jones, campaigning openly as a radical, swept to the UT student body presidency.

Gary read widely and wrote prolifically and was a major contributor to the Rag. He finally deserted Austin for New York, where he briefly edited Rat, the underground tabloid founded by fellow UT SDS member Jeff Shero, then went to Houston where he was news director for the noncommercial radio station, Pacifica, whose transmitter was damaged by bombings during his tenure.

As the sixties wore on, Gary, like other early radicals, was confronted by the souring of the revolution which had begun in such idealism. The Movement, though peaking in energy, support, and influence, was on the verge of collapse, plagued by bitter struggles from within and government harassment from without. A series of political trials exhausted time, energy, and what little money the radicals had, and infiltration by the CIA, FBI, and other intelligence agencies exploited the ideological divisions that were threatening to tear the Movement apart. In Houston Gary tried to define the Movement’s goals in a manifesto he wrote for a yippie-like group called the Red Coyote Tribe:

“The new culture is important because it bears traces of a better way of living . . . It would break down the barriers that separate men and women from each other’s love and help. It would eliminate the notion that individual conquest of people and things is the only proof and justification of existence. Beyond the possibility lies the dream: the challenge of taming this techno-marvel and putting it in the service of all the peoples of the globe.”

That was mid-sixties rhetoric, but this was the late sixties. Lofty visions were fading fast; the old SDS was no more, and radicals were divided into warring factions of violence freaks and tedious ideologues. Assassination, riots, the war, Nixon, Agnew, Kent State: violence was the order of the age. It was a time of disillusionment and transition—he had won, but he had lost—and so, like Dennis and Judy Fitzgerald, Gary went the communal route in Arkansas. But that too fell apart. Then he moved to Santa Fe, where he cultivated the craft of carpentry that he had developed in Arkansas. Now he does contract construction work in Houston and Austin. Despite his academic background, his experience in broadcasting and writing, and the breadth of his reading, he says he now finds gratification only in working with his hands.

“I still feel it’s an unjust and authoritarian society,” Gary says, “but I have more questions than before. As for our Movement, the book is closed on it.” And he sounds more than a little relieved that “I no longer feel the weight of my shoulder on the wheel of history.”

In 1968 Barbara Cigianero was on the verge of becoming a nun. After two years at Our Lady of the Lake Convent in San Antonio, she was a novice and wore a habit. But not even a convent could be insulated from the turbulence of the times, and many of the women, including Barbara, were asking more and more questions.

“It was a very restrictive setting,” says Barbara, “and I got to the point where I questioned everything. Their answers were always, ‘It’s a matter of faith.’ I had always thought that people could be persuaded by rational, logical argument. But I saw that in the Church it didn’t work that way.”

She decided not to take her vows and fled the convent. After attending Texarkana Junior College, she enrolled at the University of Houston in the fall of 1969. She didn’t know much about politics, but the same desire to help people that had steered her toward the convent now led her to volunteer for Cesar Chavez’s United Farmworkers Organizing Committee. She dropped out of school and spent two and a half years working full-time for the farmworkers and learning the rich history of the American labor movement.

“It’s hard to imagine anyone working with the farmworkers and not being radicalized,” Barbara says. She began to oppose the Viet Nam War and to work with feminist and environmental groups. She came to perceive these social problems not as isolated mistakes or unrelated malfunctions but as symptoms of a far more basic ailment, an inherent affliction of the American political and economic structure. This was a path traveled by many: from an idealistic involvement with a single issue—the war, civil rights—to a radical analysis that named the System the culprit.

Barbara became a militant feminist and to make a point took a job as the first woman apprentice in a machine shop. She got four raises, but after a year she was ready to move on, and she says she couldn’t have been happier about leaving: “I never wanted to relate to a machine again for the rest of my life!”

Now 28, Barbara is an administrative secretary with the State Board of Pardons and Paroles in Angleton. Her responsibilities range from traditional secretarial work to checking out community rehabilitation programs and doing background research on inmates seeking parole. It’s the kind of job she or her friends might have sneered at during her years in the Movement, but she now considers it consistent with her past and scorns those purists who chastise anyone for working within the system.

“What do you say to people who are oppressed?” she asks. “ ‘You just have to wait for the Revolution’? No. We can take some of that crap off their backs right now. We’ve found errors or mix-ups in some cases and it’s made the difference in someone going free.”

Barbara acknowledges that her post-Movement expectations are lower (“You no longer think that you can somehow personally end the war or that you’ll be on the cover of Time”), but she believes that former activists have a special edge in her line of work. “People with experience in the Movement have learned that they can make a difference,” she says. “They are less likely to be overcome by the sense of futility that bureaucracies nurture. Every once in a while a case comes up where my being there makes a real difference for someone. The Movement instilled in us a sense of hope that we carry with us in the real world.”

Barbara Cigianero went from religion to activism; Victoria Smith took the opposite course. She grew up in Minneapolis, attended the University of Minnesota, and graduated with a degree in journalism in 1967. She worked for a short time as a reporter, but her interest in radical politics, acquired while she was in college, drew her to the national SDS headquarters in Chicago. She visited there in late 1967 and decided to stay. Soon she was running the print shop—an uncharacteristic job for a woman, even in the supposedly liberated New Left where liberation all too often meant that women participated freely in sex, but when it came to work, might be confined to typing and making coffee.

The print shop was a scene of constant activity, churning out strident leaflets, flashy posters, political brochures, and New Left Notes, the SDS monthly tabloid. But the headquarters was the scene of constant tensions and vicious personal quarrels, and by the summer of 1968 Victoria was ready to move on. She spent the next year in New York working for Liberation News Service (LNS), which provided Movement news to underground, community, and campus newspapers throughout the country. In Austin the Rag subscribed to LNS and so did the UT student newspaper, the Daily Texan. At its peak the underground press had a combined circulation of nearly two million; it opened up the traditional media, forcing coverage of stories that otherwise would have gone unreported, and had a lasting impact on journalism in the United States. LNS was the nerve center of this heady effort. But it was also the scene of the ideological struggles and psychological tensions that increasingly hounded the Movement. It was just what Victoria had left behind in Chicago, and she looked for a calmer place. Dennis and Judy Fitzgerald, Victoria, and I met in New York in 1969 and decided to start an underground paper in Houston. That was the beginning of Space City News. The paper quickly became a major force in the Houston counterculture. It was run by a collective that shared responsibility for the paper’s editorial direction and workload. But Victoria was the backbone of the paper, a writer, editor, and organizer. For the next three years, she held the paper together and helped it expand beyond its radical audience.

But once again things didn’t last. Financial malnutrition sapped the energy of the newspaper (by this time named Space City!), and the inevitable personality conflicts manifested themselves again. In August 1972 the paper finally collapsed, just as the Movement itself was on the verge of collapse, and Victoria, like many of the committed radicals, went through a tumultuous period.

Now, after a brief fling at traditional journalism, a stint with an ad agency, and a job as a waitress, she is still in Houston. But there is a major change in Victoria Smith’s life: she has found religion. Once an avowed atheist, she is now a member of the Episcopal Church; she sings in the choir and does volunteer public relations work. She says she had faith all along but was repressing it.

“I finally had to acquiesce in the belief that things are working toward a purpose, that it’s not just chaos. The most important thing in my life now is my prayer life and my spiritual growth.”

Her basic political beliefs are unchanged (“I’m a firmer believer in communalism—communism—than ever before”), but she regards the failure of the Movement as a spiritual one:

“This little group of people, we thought we could move the world. It was a time of tremendous freedom and exhilaration, but we never had any sense of temperance, of moderation. I used to be raw nerves to everything.”

“We were running on some incredible energy, and our batteries were running down—and we had no generator. Hope and faith: there’s a generator.”

Just a few years back Mike Kinsley did a lot of drugs, was active in SDS, and sold underground newspapers on Houston street comers. Now he is a county commissioner of Pitkin County, Colorado, home of Aspen and John Denver.

Mike is one of a large cadre of sixties, activists now involved in electoral politics. Many hold public office. One of the Chicago Seven, John Froines, is a state health official in Vermont. His codefendant, Tom Hayden, ran for the Senate in California. Former antiwar mobilizer Sam Brown is Colorado state treasurer, and onetime radical Paul Soglin is mayor of Madison, Wisconsin.

They have joined forces with others who call themselves progressives or populists, hoping to pool experiences and create a political network that some envision as evolving into a political party. The National Conference on Alternative State and Local Public Policies is their organizational focus and, despite its tedious name, its several gatherings to date (including a national conference in Austin last summer) have proven fruitful and, some participants say, even exciting. The rhetorical excess and venom which marked sixties conferences are notably absent. In their place are seminars on taxation, environmental management, and utilities regulation.

Such a development was unthinkable in the sixties, when a survey of radicals would probably have rated electoral activity well below apathy on a scale of acceptable behavior. And no wonder: a radical was someone who believed that even progressive politicians couldn’t make meaningful changes, for the real problem lay in the nature of the system. Liberals created only the illusion of change.

Mike Kinsley is one of the “new pragmatists,” as they are tagged by political analysts. He attended the University of Houston in the mid-sixties and was involved with SDS, but in the beginning he was more a yippie-style cultural revolutionary than a theoretical political radical. During large protests on campus, he and his friends would blare out recorded rock and roll music, smoke marijuana, and urge bystanders not to go to class. “If you’re gonna have a revolution, you gotta have fun,” was Mike’s philosophy.

The environmental movement accelerated Mike’s political radicalization. He wrote a paper on water pollution and then saw human feces floating in Buffalo Bayou. “That’s when I really understood there was a problem,” he recalls. He peddled copies of Space City! on Main Street near the Shamrock Hilton and was involved in a riot at Texas Southern University. But he was never a theoretician like Gary Thiher, and he maintains that the Movement did little to prepare him for electoral politics, because he never really had an ideological basis to accompany his radicalism.

Just as the Bolsheviks of 1917 were certain that all of Western Europe would follow their lead, so many radicals in the sixties really believed that the United States was on the verge of revolt. They set their stakes so high that nothing short of total revolution could be seen as a victory—hence they guaranteed themselves continual defeat and frustration. It was a lesson Mike Kinsley took to heart.

“It’s very scary to win,” he says. “It’s fun to lose; it’s easy to lose. I won, and I don’t know what to do with it. When I was out trying to shut down the university, we had only one focus. Now I’ve got to figure out things like which mental health clinic to fund.”

David Mahler came to Austin in 1965 from a small conservative college in Pennsylvania. He was a graduate student and a folk musician. At folk festivals he’d had minimal contact with hippies and radicals, but by his own description he was straight arrow. He knew almost no one in Austin and remembers those first few months at UT as the loneliest, most miserable time of his life.

Seeking companionship as much as political enlightenment, he went to a meeting of SDS, an organization he’d read about in Playboy. He liked the people he met and they invited him to a party at the Rag office, which was about to publish its first issue. There was a local band jamming like crazy and a colony of artists, dopers, and political ideologues crowded into the cluttered frame house on Rio Grande Street. The energy was intoxicating. Within a few weeks he had dropped out of graduate school to work fulltime on the Rag. That phase of his life lasted four years, during which time he became active in SDS, eventually serving a term as chairman of the local chapter.

In 1969, about the time that the movement’s influence peaked in Austin, Dave and several other SDSers interested in education moved into rural Travis County to start an experimental school called Greenbriar. The school is still functioning, making it something of a rarity: a sixties alternative institution that is still thriving. It is organized as a free school; 50 to 75 students, who range in age from five to seventeen, determine for themselves when and what they want to learn. Tuition, which is set by a committee of parents and staff, is $20 to $100 a month and is based on ability to pay. The school is not accredited by the Texas Education Agency.

Dave Mahler is one of two founders still at Greenbriar and one of the first to temper the revolutionary rhetoric of the sixties. When the school started, he says, “We were reducing our expectations. We didn’t think we were going to change the whole country right away. But we knew that we were a little integral piece, and at least we could change this piece. And if everybody would change their own piece, then America would change.”

Like many other sixties radicals, Dave describes himself as mellower, more tolerant. He remains, however, a staunch advocate of “kid’s rights” and considers children to be “bar none, the most oppressed class in the United States. In this society we teach kids they don’t have any rights, they don’t have any control over their lives.” This philosophy led him to run (unsuccessfully) for the Austin School Board last April. “The longer we’re around,” he says, “the more we realize the extent and depth of the changes we’re advocating, and the more we realize the length of time it will take to make those changes.”

In many ways, Jeff Shero’s story epitomizes the history of the Movement and its people: he began as a conservative high school student in Bryan; gradually awoke to the injustice he saw around him; embraced, then rejected, liberalism; became a radical leader, first locally in Austin, then nationally; found himself hopelessly enmeshed in the violence and trauma of the Movement’s death throes; turned to spiritualism; and finally emerged in the midseventies with a job that could not have existed before the revolution in which he played a part.

As a freshman at Sam Houston State Teachers College in Huntsville in 1962, Jeff developed an instinctive aversion to Jim Crow laws. Though he considered himself a conservative and an anticommunist, he found himself active in the sit-ins and demonstrations that were part of an abortive local integration struggle. The civil rights movement was led by a minister who backed down when the school administration threatened to kick his Bible classes off campus. That was the end of the first attempt by a black student to enroll at the college, and it was also the end of Jeff’s respect for liberal methods.

When he came to UT in 1963, Jeff found Austin alive with sit-ins and other forms of racial protest. His growing radicalism became focused when he attended the national SDS convention in 1964. Jeff helped build the Austin SDS chapter—one of the organization’s early outposts—into the largest and most active chapter in the Southwest; later he served a term as SDS national vice president. He was a leading theoretician in the Movement, stressing grass-roots organizing and the cultural aspects of the youth revolution. He moved on to New York in 1968, founding Rat, and was active with the yippies nationally.

But New York was the end of the line for Jeff Shero. All the ideological and psychological problems that haunted the Movement seemed to become magnified there. He became disgruntled with the direction and tactics of the New Left; all around him friends and colleagues were urging violence, bombings, going underground.

“I ended up fighting for things I didn’t believe in,” he says. “The Weathermen got started, and people were bombing things—and it didn’t seem to me that the tactics were effective.” Much of the activity, especially in New York, turned out to be battles over turf. “The slogan was ‘The streets belong to the people.’ I remember fighting for Saint Marks Place, down on the lower east side. Then all of a sudden I realized, ‘I don’t like this street. It’s ugly and tawdry. I’m not happy on streets.’ The goal was stupid; it symbolized the craziness of the whole thing.”

His personal life became a nightmare. Many radical couples suffered traumatic breakups as the Movement fell apart. It coincided with the peak period of feminist anger, and Jeff was caught in the vise. He describes his wrenching break with a female companion of long standing: “There was a slow unraveling of the relationship as she got more into women’s consciousness. Things I thought were leadership qualities she said were ego, macho. In the end she had me convinced I was a terrible man, a terrible human being.”

In retrospect, Jeff feels that much of the craziness of those Nixon years was symptomatic of a growing sense of powerlessness that led people to turn on each other. Lyndon had resigned, the country was looking for a way out of the war—but things didn’t seem any better. “You couldn’t hit J. Edgar Hoover in the nose, so you would take all the frustration out on the people around you.”

After the breakup, he had a short flirtation with Guru Maharaj Ji’s Divine Light Mission; Guru devotee Rennie Davis was an old friend. Jeff ultimately found the Guru’s message facile, but he still believes in spiritual alternatives. “I can’t conceive of a healthy movement where people aren’t spiritual.”

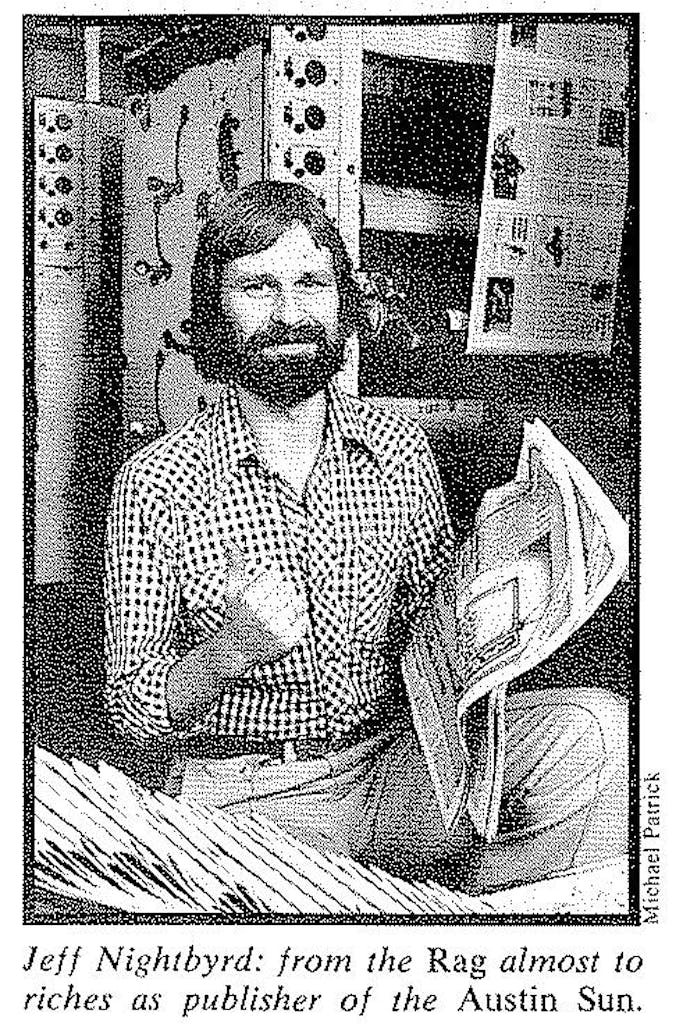

Jeff Shero—now Jeff Nightbyrd—is back in Austin, sharing a cluttered house with his dog Shagnasty. He is publishing the Austin Sun, a splashy community biweekly with a bigger budget, slicker format, and calmer editorial style than the underground papers he worked with a decade ago. The Sun carries thoughtful political analysis, photo features, gossip, a sports column, and coverage of the Austin cultural scene. The paper, which drew national attention recently when Jeff printed an in-Texas interview with fugitive Abbie Hoffman, has seen its circulation grow in two years from 6000 to 18,000. “I expect there’ll be big movements again and I’ll organize again,” he says. “But right now I’m in business.”

For the most part these sketches represent a sampling of my former associates. I have avoided the “one of each” approach of creating arbitrary categories (junkie, jailbird, gay activist, politician) and then filling the slots. I will admit, though, that I did make a significant effort to locate at least one heavy-duty sell-out, someone who has made the symbolic leap to the pinnacle of financial power, preferably a stockbroker or banker or junior executive in the family business.

Well, I found none. I have no doubt that there are people in such positions who were on the fringes of the Movement—who smoked dope and wore bell-bottoms and joined a demonstration or two. But none of my friends from the New Left has made such a turnabout, nor do they know of anyone who has.

I did find Walter White, though. His story offers sharp contrast to the trends I’ve encountered. Walter, now 35, was active in civil rights demonstrations as early as 1959 and vocally opposed the Viet Nam War long before it was popular to do so. He was in Naval ROTC, and when he left school in 1962 the Navy tried to ship him over. He marched down and informed them he wasn’t going. He got away with it too. The Navy let him out of his obligation, and Walter became a founding member of the Houston SDS chapter and helped organize the early peace vigils at the LBJ Ranch.

When I visited Walter recently, he was manager of marketing and sales for Schmidt Manufacturing in Houston, a firm that produces sandblasting equipment. Since that time he has left the company “under duress,” a victim of a corporate battle in which Walter, a minority stockholder, was on the losing side. At press time he was working with a Houston painting contractor but still owns stock in the company.

Walter was pulling in more than $25,000 a year at Schmidt, in addition to his piece of the business. Comfortable, but far from financial upper crust. He stressed that his firm was a leader in safety standards, paid its employees well, had a black foreman, and staffed the reception room with a black man “instead of a pretty girl.” And he pointed to his personal support of the Big Thicket Association and other causes and to his work for politicians like Barbara Jordan and George McGovern. But, he said, he found himself “less willing to stick my neck out, and I have less time. And I have practical considerations now—I have a family, I am responsible for the welfare of five people.”

In any event, Walter says he never was an ideological leftist. “I really hated that goddamn war,” he says, “but I’ve never been concerned with the way the United States is organized in general.” Just the same, Walter White is proud of his involvement with the Movement and thinks the country will see another period of heightened radicalism before too long. “If there were another movement,” he says confidently, “I would be involved in it.”

“At least, I hope I would.”

In his scholarly history of SDS, Kirkpatrick Sale summed up: “. . . though it achieved none of its long-range goals, though it ended in disarray and disappointment, it left a legacy. . . of deep and permanent worth. It shaped a generation, revived an American left, transformed political possibilities, opened the way to changes in the national life that would have been unthought of in the fifties. . . SDS stood as the catalyst, vanguard, and personification of that decade of defiance.” Pollster Louis Harris wrote three years ago that the Peace Movement “succeeded beyond its wildest dreams.” In 1967, according to Harris, a majority of the American people considered the following types to be dangerous or harmful to the country: atheists, black militants, student demonstrators, prostitutes, and homosexuals. In 1973, the bad guys were people who hire political spies, generals who conduct secret bombing raids, businessmen who make illegal campaign contributions, and politicians who use the CIA, FBI, and Secret Service for political purposes.

If there are any final words, perhaps it’s best if they come from the radicals themselves. Jeff Nightbyrd says the Movement failed in the sense that total revolution was the goal. “The dream got so grandiose—our definition was a new world order, which has never come about, anywhere.” Then he details concrete victories. “We built a movement that had a very direct effect on our war effort. The TJ.S. military could have used nuclear bombs, nerve gas agents, and much more biological warfare. If it weren’t for our movement, Viet Nam would have been destroyed.” About cultural values Jeff says, “America was tight and intolerant. The acceptable levels of activity have changed. The United States is finally becoming a little bit cosmopolitan. Different lifestyles are tolerated.” To Gary Thiher, “The most gratifying thing is that, when you look back on it, we were absolutely right on just about everything. Nobody was being paranoid. To the contrary, we were naive. We figured we were being watched and wiretapped, but we never guessed the true extent of it.”

Dennis Fitzgerald is less optimistic in his assessment. “It was a pendulum swing more than a revolution, a reaction to a distorted and exceptional period in our history. Kids were reacting against the excesses of their parents, the first true-blue suburban Americans. To a large extent it was a media event. I question the extent to which it changed American society. No doubt it changed my life. Maybe all of us are not so good or revolutionary as we thought we would be, but we are better than we would have been otherwise.”

Perhaps the person who best put the Movement in perspective was Dallas underground editor Stoney Bums. “Looking back on it,” he told me, “we struggled so much, hard work and struggle, but it was exciting. I’m glad I was involved. It was really historic. I sure had fun.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads