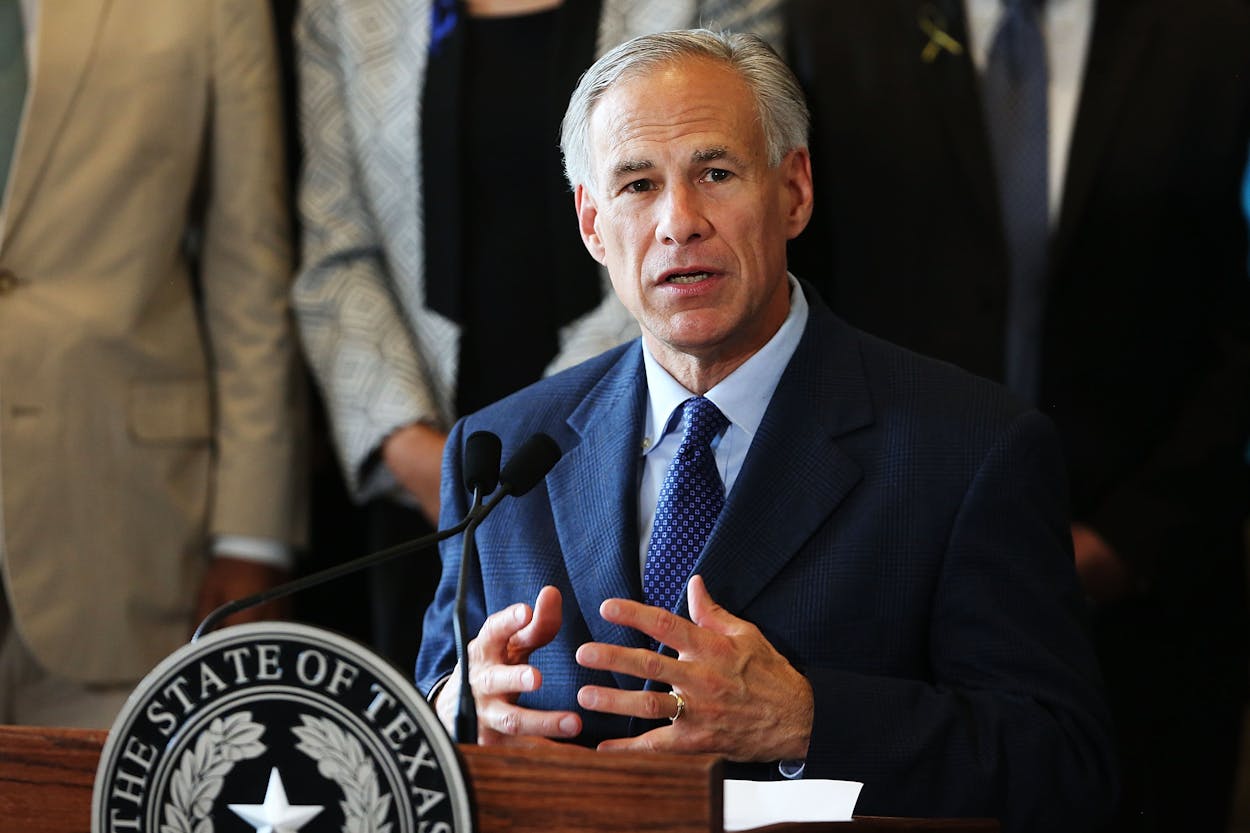

Governor Greg Abbott stole the spotlight from his allies and thwarted protestors, the news media, and Democrats Sunday evening by signing the “sanctuary cities” bill into law on Facebook Live. The video has been viewed more than 640,000 times, which exceeds the combined daily circulation of the Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, and San Antonio Express-News. It also prompted conservative commentator Glenn Beck to declare Abbott “a boss” of social media. Hosting Abbott on his talk radio show, Beck noted some were complaining about Abbott using Facebook for the bill signing. “What a coward, or a genius. You decide,” Beck said.

The actual policy behind the sanctuary city bill aside, in those five minutes and ten seconds of live streaming, Abbott and his aides took a major step in this year’s efforts by Texas Republican leaders to bypass the state’s mainstream media and obtain unfiltered access to the public. By signing the bill unannounced, Abbott’s staff denied protestors the opportunity to gather outside so that they could be heard chanting in opposition in the background. Abbott also avoided questions from pesky reporters who might want to know how he could sign a bill that is opposed by every major city police chief in the state. And though Abbott acknowledged the hard work of Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Speaker Joe Straus, and bill sponsors Senator Charles Perry of Lubbock and Charlie Geren of Fort Worth, he grabbed sole credit by not having them stand behind him as he signed the bill.

From the start of this legislative session, it has been obvious that the state’s socially conservative Republican leadership has been trying to create a new normal for dealing with a news media that is viewed as both hostile and liberal.

The Texas Senate moved first with a “decorum” enforcement that required journalists to sit only at a press table, and if the table was full, they would have to move to the Senate gallery for overflow. If a journalist wanted to interview a senator, then they had to submit a written request on a blue slip of paper, and interviews were barred in the foyer outside the chamber. Most socially conservative senators declined interview requests or delayed answers until past most reporters’ deadlines. The crackdown on journalists was decided upon in a closed-door caucus of the Senate, which would have been a violation of the state’s Open Meetings Act if done by a city council or a school board. Texas senators, like members of Congress, often are exempt from those types of rules.

Restrictions on the news media like those adopted by the Texas Senate have in the past been declared by a federal court as a violation of First Amendment protections of a free press. Long before he was The New York Times Washington bureau chief or the editor of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Bill Kovach was a young reporter for the Nashville Tennessean covering the state’s Senate. When a Senate committee attempted to meet in secret, Kovach, with the permission of his editors, refused to leave the committee room. The Tennessee Senate retaliated by banning reporters from the chamber and blocking the doors of the Senate chamber to require them to watch the proceedings from the spectator gallery. The Tennessean went into federal court and had its floor privileges restored.

The Senate rule, wrote Chief Judge William E. Miller, “represents an unreasonable prior restraint upon plaintiff’s freedom of the press and freedom of speech and is itself unconstitutional and void under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.” Miller went on to write that newspaper access to the Senate floor was not just a matter of whether it was ‘convenient for the Senate.” Whether it is a right or a privilege for the press to have a place on the Senate floor, “it cannot be plausibly denied that the interest involved insofar as a newspaper is concerned is one of real if not indispensable value. It gives direct, immediate and effective access to an important and vital source of state news. Denial of such an opportunity…would place a serious handicap and burden upon any newspaper which could not be materially alleviated by access to the Senate gallery.”

The point of the Texas Senate enforcement was not to punish journalists but to set the stage to bypass them in favor of advocacy groups like Empower Texans and Texas Values, which often give unchallenging video interviews to legislators and public officials who support the bills they are backing, particularly on socially conservative legislation involving gay rights and opposition to abortion.

James Cardle runs a conservative news site called Texas Insider, which he said has 172,000 email subscribers. Cardle said he and his staff try to give his audience news conservative coverage based on issues rather than agendas. Many of the politicians who agree to appear in his videos or on an associated talk radio program do so because they have a perception that they will get a “fairer shake” than from the mainstream media. “All we’re trying to do with Texas Insider is truly reflect the Texas populous, because that’s our customer,” Cardle said. “You look at the Supreme Court justices last time, every stinking one of them got 59.8 percent to 61 percent (of the vote). That is the baseline of the Texas Republican, I would call them conservative … That is who the news customer in Texas is.”

Conflict between the news media and the powers that be is nothing new. Union General William Tecumseh Sherman thought the Civil War reporters covering his campaigns against the Confederacy were nothing more than spies whose reports were ”false, false as hell” and the people who read them were “the non-thinking herd.” Sherman’s frustration arose in no small part from his version of the internet, the advent of news reports spreading rapidly because of the telegraph. The Confederacy might not be receiving the dispatches directly, but soldiers on the front line were trading southern tobacco or northern coffee and newspapers.

In the presidential campaign of last year, the campaigns of both Democrat Hillary Clinton and Republican Donald Trump took shots at the mainstream news media. Since becoming president, Trump has turned attacks on the media into a form of deconstructing art in an effort to destroy the credibility of those who question his administration.

The effort to isolate the news media in Texas is a phenomenon of just the past several years. Governors Bill Clements, Mark White, and Ann Richards were available to the news media at least weekly and often daily during legislative sessions. Governors George W. Bush and Rick Perry did not hesitate to talk to reporters covering their events. Past lieutenant governors routinely met with journalists at the press table. But Patrick has almost completely halted that practice, and Abbott rarely meets with journalists and his communications office has a closed-door policy and usually only wants to communicate by email. (I sent his press secretary an email today asking simply why Abbott did the bill signing on Facebook and received no reply.)

In the days when the Texas Capitol news media could catch a governor on the front steps, the interactions were so natural that the Clements administration formalized the gatherings at lunch when the Legislature was in session. Pigeons cooed on the ledge above, and tourists stopped to snap pictures. Television camera crews jostled for position, while the pen pushing print reporters strained to hold their tape recorders close to the governor. Asked whether he preferred the outdoor news conference to the ones in his reception room, Clements replied, “I think it’s lovely. Maybe we’ll get some pigeons with us.”