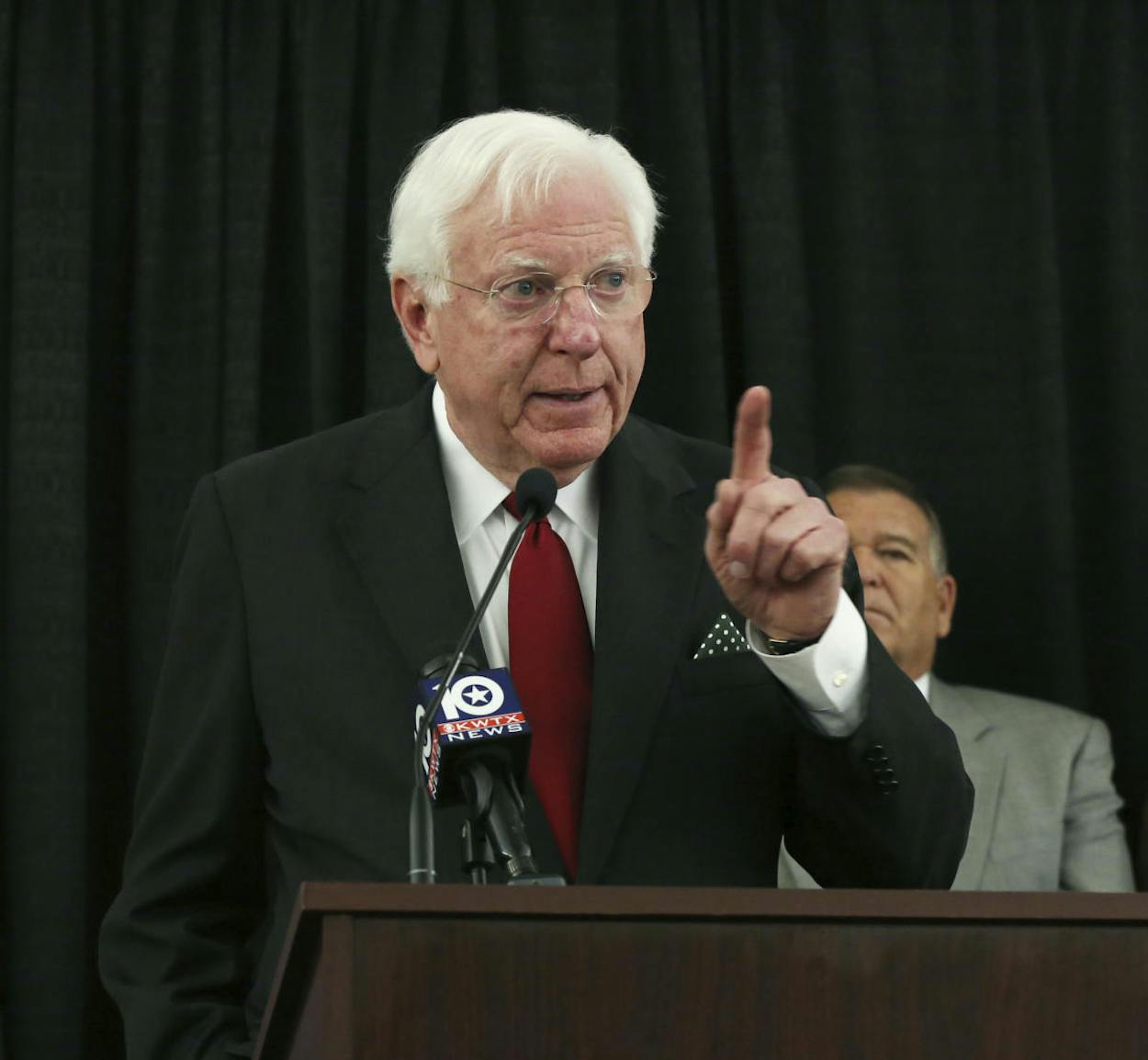

Former governor Mark Wells White Jr. won the state’s top office by promising to put a housewife on the state commission that regulated utilities, overseeing major reforms in public education, and insisting both on raising taxes during an economic downturn rather than gut higher education and taking the blame for doing so.

White died of a heart attack Saturday at his home in Houston, according to the Houston Chronicle.

A Democrat, White defeated incumbent Republican Governor Bill Clements in the 1982 election, and then Clements made a comeback to defeat White in 1986. White made a final effort to win the office again in the 1990 Democratic primary, but he came in third behind Ann Richards and Jim Mattox. “I didn’t pledge perfection,” he said in defending his term as governor. “I pledged commitment. The schools are better today than when I took office. You can’t give credit for that to anyone or anything else other than the time I spent there.”

White presided over state government at one of the most tumultuous times in modern history, when the reality set in that the state’s oil-based economy was going to become cyclical with euphoric highs followed by hangover lows.

Born in Henderson County in 1940, White was the son of a teacher. During World War II, his family moved to Houston, where his father worked in a shipyard. Mark White and his future wife, Linda Gale, met at Baylor University. He was a law student, and she was in her senior year. “From day one, we talked about government and serious issues,”Linda Gale told me. “And that was sort of a twist on my dates.’”

When White was named Texas Secretary of State in 1973, he placed a Baylor rug in the foyer of his office. Baylor President Abner McCall administered White’s oath of office as attorney general in 1979. As governor, White turned to Baylor graduates time and again for appointments to head state agencies. When he made his come-back bid in 1990, however, he lost the Democratic nomination to two other Baylor graduates, Mattox and Richards.

In the closing era of Democratic domination in Texas, White won the attorney general’s office in the 1978 election by defeating future U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, even though Clements won the governor’s office in that election. White became the Democratic foil to Clements for the next four years. White sued coal companies in an effort to lower Texas utility bills, and when he ran against Clements he did so by promising to name a housewife to oversee the state commission that set utility rates prior to deregulation. White also promised teachers a pay raise.

As governor, White had to exercise diplomacy with House Speaker Gib Lewis of Fort Worth and Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby of Houston–both of whom supported White’s goals on education. But Lewis made it clear that he would not support a teacher pay raise without accountability. The result was a one-time teacher literacy test in exchange for the pay raise, which caused resentment among White’s political base.

But White pushed through $4 billion in tax and fee increases to pay for improvements in public education. The most controversial aspect of his reforms, however, was the “no-pass, no-play” rule that had a devastating impact on Friday night football in the early years.

White might have survived that if Saudi Arabia had not glutted the oil market in 1985. Texas was undergoing a massive boom in office building construction that was financed by the recently deregulated Savings and Loan industry by President Reagan. Oil was the collateral. Gambles were the thrift industry’s investment strategy. And overnight it all vanished like the devil’s ghost. Oilmen went bankrupt. Thrifts started failing. And the state suddenly found that more than $1.6 billion in spending that had been appropriated earlier in the year no longer existed.

White went before the Legislature and quoted one of Texas’s founding fathers, Sam Houston, “Do right and risk consequences.” White told the lawmakers that if they needed someone to blame for a tax increase, “Blame me.” They did, and so did the voters.

“So much for guts and glory,” White joked after his 1986 election defeat.

It would be easy to look upon Mark White’s single term as governor as a failure because of his re-election defeat. But student athletes perform better today because no pass, no play forces them to, class size was reduced to make teaching more effective, and the Legislature increased education spending 26 percent to equalize state public spending statewide.

At the end of White’s term, the state paid 67 percent of all education costs in Texas. Today, the state’s share is down to 38 percent. One could reasonably argue that local property taxes are rising in part because no politician today has the courage to say, as White once did, “Blame me.”