On Monday, voters in Iowa will be the first in the nation to choose their candidates for this year’s Republican and Democratic presidential nominations. And in a week of reporting, I’ve come to two key conclusions about the 2016 caucus. First, the stakes are higher than usual—especially for Ted Cruz, who probably needs a decent showing given how conservative Iowa Republicans are. Second, no one has any idea what’s going to happen.

Because Iowa holds the first formal contest of the nominating process, its caucus always gets a lot of attention, but its influence is often overstated. Barack Obama’s victory in Iowa, in 2008, was unusually consequential: it was evidence that a freshman senator, with his liberal beliefs and exotic life story, could compete effectively in a state like Iowa, and field the kind of ground game that often proves decisive in this idiosyncratic context. But a win in Iowa that same year ultimately did little for Republican Mike Huckabee, or for Rick Santorum four years later. The state itself isn’t necessarily a good proxy for the nation as a whole and its electoral process is sui generis. The results of the Iowa caucuses are inevitably subject to interpretation, and may ultimately be dismissed, on the basis that they have little predictive power. That may be the case on the Democratic side this year. For all intents and purposes, there are only two candidates running for the party’s nomination, and it’s widely assumed that Hillary Clinton will be the eventually be the nominee, even if Bernie Sanders wins in Iowa, as he might.

On the Republican side, however, Donald Trump remains the clear frontrunner in a crowded field, followed by Cruz. The Iowa caucus represents an opportunity for candidates like Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, John Kasich, Chris Christie, and Rand Paul to emerge as someone who can plausibly compete with Trump or Cruz. Not the last chance, perhaps, but a potentially crucial one. A strong showing in Iowa would insulate a candidate like Rubio from criticism if he doesn’t medal in New Hampshire—in Rubio’s case, I think, it certainly would—and make it easier to persevere as the field narrows.

More importantly, the Iowa caucus gives Republicans a chance to address their party’s most pressing problem. As I predicted in August, Eeyore-ishly, Trump’s popularity has proven more durable than most observers thought it could. National polls show him with nearly twice as much support as Cruz and the same is true in most state polls. Iowa is the only exception. I’ve heard a number of people—national observers and Iowans alike—posit that that the caucus might be the GOP’s last chance to thwart Trump’s bid for the nomination. That seems plausible to me; as I wrote in November, I doubt that Trump is emotionally equipped to deal with being a loser.

Perhaps most importantly, the Iowa caucus will be a referendum on reality. The 2016 presidential primaries have been thoroughly bizarre. Clinton has some known baggage and serious vulnerabilities, and yet the only candidate who has made a serious effort to challenge her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination is a self-described socialist and staunch Second Amendment supporter. And that’s the sane presidential primary. Many Republicans, meanwhile, are still clinging to the hope that Trump’s status as the frontrunner is somehow an illusion, and that his support, as measured in hundreds of polls by dozens of pollsters, won’t translate into ballots. This year’s caucus may be a welcome relief, or it may be a bracing reality check. It will at least give us a set of facts to grapple with, rather than premises about American politics that have already been proven tenuous by the campaign at hand.

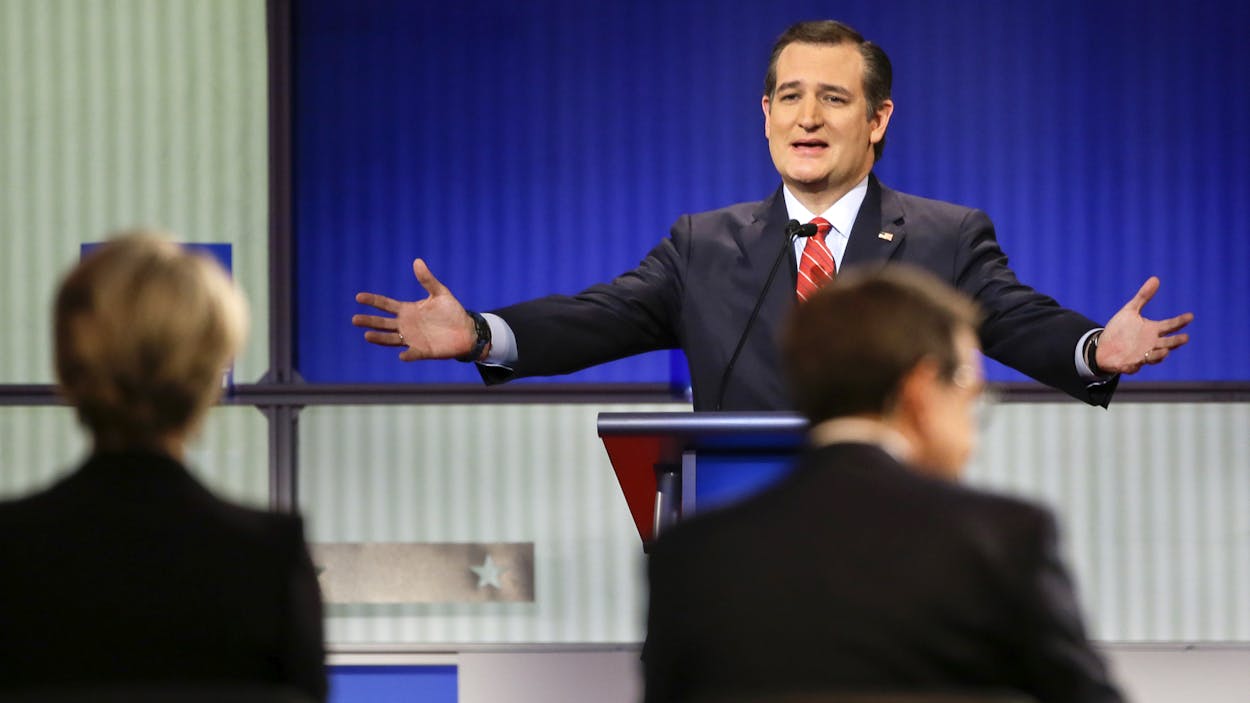

I assume it’s common for politicians, campaigning in Iowa, to talk about the heightened historical importance of the election, and to emphasize the state’s solemn and unique responsibilities in considering the candidates running for president. Since this is my first time covering the Iowa caucus, I can’t say whether they’ve been offering such exhortations more often than usual. But on Friday, when Cruz told supporters at a town hall in Wilton that Americans are “literally standing at the edge of a cliff,” I couldn’t bring myself to scoff at the melodrama, or even his misuse of “literally” in a state where I have yet to see even a steep curb.

With all of that in mind, it’s been unsettling to realize that no one has the slightest idea what to expect. The Des Moines Register’s final poll, released on Saturday, found that Trump had retaken the lead, with 28 percent. Cruz’s standing had slid to 23 percent, and Rubio’s had risen to 15 percent. The trajectories are plausible, in light of an outbreak of hostilities between the senators; Rubio had been on an upward trajectory even prior to that, and last week was hard on Cruz regardless. As it began, he was under attack from several rivals, including Huckabee, and Trump, whose fear-mongering about Cruz’s Canadian birth has had more resonance in Iowa than I would have expected, considering how snowy and civic-minded the state seems to be.

Still, the Register’s poll found that fully 45 percent of respondents were undecided. And one of the first things I learned, on my arrival in the state, is that it’s hard to be a pollster in Iowa: even the voters who have made up their minds are notoriously vulnerable to being persuaded during the carpool from the church, or being moved by a supporter’s pitch during the caucus itself. Even in normal years, the caucus involves an unusual amount of uncertainty. This time around, Trump’s campaign has created profound confusion across the nation. I would describe the mood, here in Iowa, as bewildered and, this being the midwest, stoical.

That’s my mood, at least. At the moment, it seems to me that America’s leading voices of reason are Iowa evangelicals, Bernie Sanders, and Fox News. With that said, I’d expect Cruz to win on Monday and, frankly, I hope he does. That has less to do with my perspective on Cruz, which is admittedly unusually sanguine, than with my concerns about the alternative. At the moment, a lot of Iowans seem to be wavering between Rubio and Cruz. That’s all well and good, but still: Trump is the national frontrunner, and I met an Iowan yesterday who told me that his only hesitation was that it doesn’t seem like a good idea to equip someone so quick-tempered with a nuclear button. Though it would be premature to say that Cruz is the only Republican running who can compete effectively in this context, he is the only one who has shown any capacity for doing so thus far.

With that said, I wouldn’t be surprised if Trump underperforms expectations Monday. I’ve heard a fair amount of speculation about whether his supporters will turn out; from what I’ve learned this week, I’m more curious about what will happen if they do. Trump’s appeal, in Iowa and elsewhere, has nothing to do with ideology, principles, or experience. It’s essentially emotional. His message resonates with Americans who feel that no one has been speaking to them, much less for them. His supporters may well be motivated to turn out to vote. To do so in Iowa, they’ll have to perhaps brave a snow storm to attend a caucus, where—per the state’s longstanding tradition—they’ll be seen, heard, and overwhelmed by the solicitous interest and concern of their neighbors. That may serve as a corrective. If so, the 2016 Iowa caucus will be illuminating indeed.