In 1986 a young reporter named Jason DeParle received a scholarship that allowed him to spend a year studying urban poverty in Leveriza, a bustling slum in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Soon after arriving, he moved in with Tita Comodas and her five children, who hosted him off and on for eight months. Tita, the eldest of eleven children, had quit school as a teenager at her father’s insistence and moved to Manila from the countryside to work in a factory; her husband, Emet, worked in Saudi Arabia as a pool maintenance man. Emet hadn’t wanted to leave his family, but with the expense of raising a large family bearing down on them—their eldest daughter, Rowena, required costly care for a congenital heart condition—the couple decided that their meager salaries wouldn’t do. Cleaning pools abroad paid Emet ten times the wage he had been earning in Manila.

DeParle returned to the United States a year or so later and has spent the decades since reporting on the plight of working people for the New York Times. Over the years, he stayed in touch with the Comodas family as various members traversed the globe in search of a better life. All five of the Comodas children followed their father into overseas work, spending time in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Qatar, and the U.S. Seven years ago, DeParle once again immersed himself in the family’s life, reconnecting with Tita and Emet’s daughter Rosalie and her family in Galveston, to document the agonies, triumphs, and transformations of migrant life in the twenty-first century. His new book, A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century (Viking), uses their example to argue for the value of immigration to the immigrants themselves, to the countries that receive them, and to the countries they leave behind. It’s an admirably sober and sympathetic treatment of a topic that right now evokes the worst impulses in many Americans, though it may, in the end, be too sympathetic to see its subject as piercingly as it needs to.

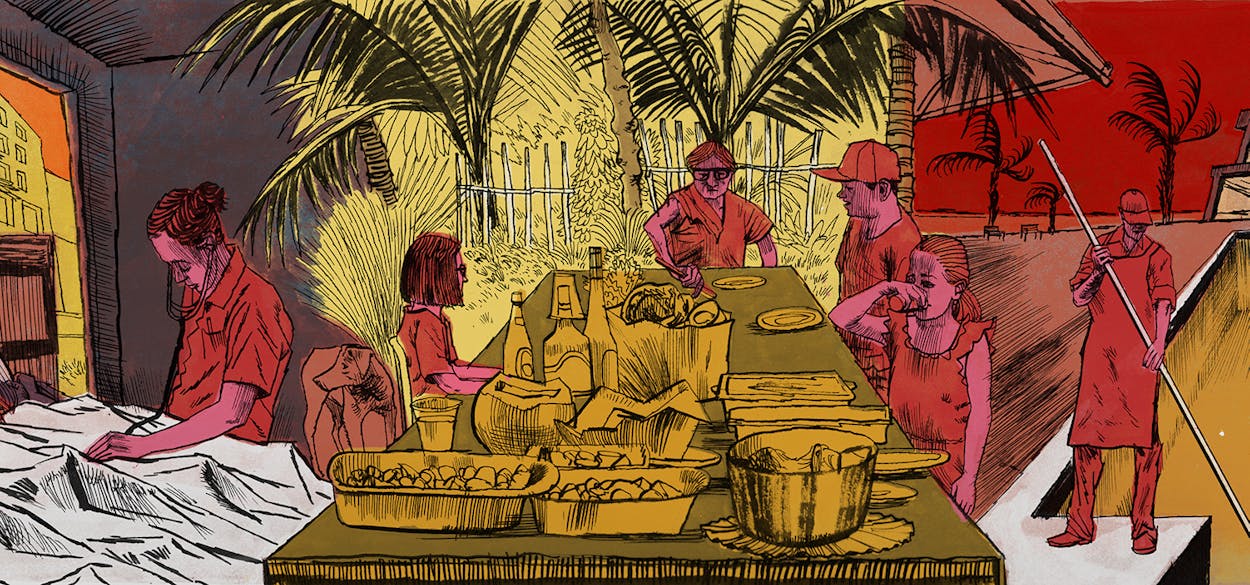

What makes DeParle’s book stand out is its focus on women immigrants, who tap into reservoirs of resilience, ingenuity, joy, and grit as they make their way in foreign, often hostile lands. While DeParle’s narrowly economic take can at times feel pat—migrants, in his view, are law-abiding, productive people and therefore worthy of inclusion in the great American story—he has leveraged his unusually close-up access to trace a fascinating narrative of female empowerment against the merciless machine of globalization.

To tell the story of the Comodas family, DeParle takes us back to his time in Leveriza, which he describes as a cauldron of poverty, filth, and corruption. In response to such destitution, in 1974 Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos instituted a program to place his citizens in temporary contracts with overseas employers. Saudi Arabia and its neighbors in the Persian Gulf hired educated Filipinos to build and operate airports, power plants, hospitals, and shopping centers. Marcos believed that Filipinos working abroad—many of whom would send most of their earnings home, a form of subsidy known as remittance—would raise incomes and stabilize the nation. “No country does more to promote migration than the Philippines,” DeParle writes. “The $32 billion that workers send home accounts for 10 percent of the GDP,” making migration the country’s “civil religion.”

After an agonizing visa process, Rosalie arrived in Galveston—“a humid curiosity with a silty beach,” in DeParle’s assessment—to work at the UT Medical branch.

In Manila, DeParle got to know the serious-minded Rosalie when she was fifteen years old. She eventually went to nursing school, traveled to Saudi Arabia in her mid-twenties to work, and met and married a kindhearted Filipino cement-factory worker named Chris Villanueva. In 2004 the couple moved to Abu Dhabi, and then, in 2012, after an agonizing visa process, Rosalie arrived in Galveston—“a humid curiosity with a silty beach,” in DeParle’s assessment—to work at the University of Texas Medical Branch, which was looking to hire foreign nurses to staff a new medical-surgical ward. (There were twelve Filipinos in Rosalie’s cohort of hires.) Upon arriving, Rosalie and her fellow nurses agreed it was “not a place you’ll be excited to see.” Rosalie worked the night shift for $30 an hour, and after her immediate family joined her in America, Chris took on much of the responsibility for raising their three children.

UTMB’s demand for foreign nurses reflects a long-running trend in the American health-care system. In the nineties, poor working conditions, spurred by cost-cutting, had dissuaded Americans from pursuing careers in nursing. Meanwhile, the need for nurses spiked thanks in part to the explosive growth of the elderly population, forcing clinics and hospitals to look abroad. “In the beginning of the twenty-first century, about a third of the [nursing] workforce growth, fifteen thousand nurses a year, came from overseas,” DeParle writes.

Following the daily lives of Rosalie and her family, DeParle displays his empathy and ethnographic skill. In one passage, he observes Rosalie during a night in the ER, when she deals with a patient who had lost a foot to diabetes and feared losing the other. “Rosalie raised [the foot] to avoid swelling, eavesdropped on his bowels, and checked the feeling in his remaining toes, of which there was little.” After the patient compares his suffering to that of the Biblical figure Job, she reminds him that “God is just,” which seems to comfort him. DeParle’s belief in her power as a caretaker, a healer, and a woman of faith shines through.

Rosalie’s entry into the overseas workforce coincides with what DeParle calls the “feminization” of migration. As DeParle tells it, this shift occurred as the demand among rich countries for caregiving labor—supplied disproportionately by women—jumped. The Philippines demonstrated this change in stark terms: in 1975, women made up 12 percent of the Filipinos who left the country to work abroad; by 2005 that number had shot up to 72 percent.

But even as migration has raised the income and status of Filipino women, it has serious downsides as well. Many Filipinas who travel abroad are assaulted, psychologically abused, and even murdered. Domestic tension is common, as men feel themselves displaced as the breadwinners by their wives and often act out in troubling ways. (DeParle witnesses Rosalie in a particularly bitter mood after she has a fierce argument with Chris, who hasn’t managed to find good, steady work in the U.S.) And those who move to foreign countries—ironically, often as caregivers—frequently miss their own offspring’s childhoods.

As virtually all immigrants in America come to know, it’s the formation of communities and networks that allows them to thrive and to bridge the gaps between their new and old lives. In one revealing episode, DeParle recounts Rosalie’s children participating in a lemonade stand project sponsored by the Galveston chamber of commerce. They offer Filipino snacks and halo-halo, a sweet, condensed milk–based Filipino dessert. When bad weather and fatigue threaten to dampen the adventure in entrepreneurship, the local “Filipino grapevine” bands together to pitch in, and the stand ultimately clears a profit. “What started as an effort at Americanization became an exercise in ethnic solidarity,” DeParle concludes.

DeParle further examines the process of assimilation by observing how Rosalie and Chris’s children adjust to life in Texas. Rosalie’s daughters Kristine and Lara struggle to learn English and pass the STAAR test while maintaining Filipino values, which the family defines as speaking Tagalog at home, respecting one’s elders, practicing religion, and staying close with other Filipinos. “Independence and free thinking, American traits, were not Filipino values,” DeParle notes. Yet it’s clear that the children’s new lives in Galveston give them outlets for expression. At school, the popularity-obsessed Kristine learns to navigate the tricky waters of friendship hierarchy, consisting of “ ‘sisters’ at the top, followed by ‘best friends for life,’ then ‘baes for life’ and ‘ride or dies.’ ‘Your ride or dies are like your best friends but not your best-est friends,’ ” she tells DeParle. Lara, meanwhile, eventually excels at school, showing a flair for writing and what DeParle characterizes as a very un-Filipino appreciation for challenging authority.

Throughout the book, DeParle’s decency feels like a balm in an era when the rhetoric—not to mention the policies—surrounding immigration has become so toxic. But while the multigenerational story of a Filipino family offers a powerful rebuttal to the loud anti-immigrant voices ascendant during the Trump presidency, it’s unclear whether the story of a Christian Asian family is an effective counter to xenophobia: Most of our current policies have been aimed at Latin American and Muslim immigrants. Asian immigrants have largely been spared the worst, though it seems likely that at some point they too will take their turn under the microscope.

And though DeParle acknowledges and vividly describes the flaws in our global migration system, A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves lacks the sort of deeper interrogation that the Indian American writer Suketu Mehta offers in his recent book, This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. Mehta, himself an immigrant, argues that the importation of foreign workers—now demonized in much of the political discourse—replicates an earlier age, when rich countries built their economies with stolen resources and exploited labor through colonial plunder. “They needed us to fix their computers and heal their sick and teach their kids, so they took our best and brightest, those who had been educated at the greatest expense of the struggling states they came from, and seduced us again to work for them,” he wrote in a recent piece for Foreign Policy. “Now, again, they ask us not to come, desperate and starving though they have rendered us, because the richest among them need a scapegoat. This is how the game is now rigged.”

In the face of such a thoroughgoing critique, DeParle’s argument that immigrants are worthy of our acceptance largely on economic grounds—they work hard, tend to assimilate, respect the law, and modestly ameliorate the poverty in their home countries—seems like weak tea. Immigrants, some argue, shouldn’t have to prove their right to build a life here; America has always been a nation of immigrants. One would think we would have learned from the grotesque outbreaks of xenophobia in our past—the violent reactions against Jewish, Irish, and Chinese immigrants, for instance—that our worst fears about new arrivals always turn out to be false.

Yet perhaps that argument is too naive. When racial hatred is the order of the day, maybe idealistic nostrums simply won’t get the job done. Perhaps rigorous, deeply reported, immersive journalism, aimed not at hard-liners but at moderate readers who are persuadable, is exactly what Americans need.

Just up the road from the Villanuevas’ home—by the end of the book they’ve moved to Texas City—lies Houston, a place that is celebrating itself of late as a city of immigrants. “Nearly as dependent on immigrants as it was on oil, Houston embraced its majority-minority status with business-class boosterism, while Hindu temples rose in the suburbs,” DeParle writes. And, indeed, for those looking to eat food from distant lands or take in a first-rate cricket or soccer game, there is much to celebrate. And one can find many immigrants who have achieved professional success in Houston that would have been difficult to achieve in their homelands. DeParle’s book, flaws and all, is a reminder that behind many of those success stories—and behind the stories of the many who don’t succeed—there often lies a tangle of regret, sacrifice, suffering, and family ties strained to the breaking point.

Sugar Land native Siddhartha Mahanta is a features editor at Insider, based in New York City.

This article originally appeared in the September 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “An Immigrant’s Song.” Subscribe today.