Eleven years ago brown baggers in Texas carried their liquor, not their lunch. Selling liquor by the drink was illegal, and those of us who wanted a cocktail had to haul a bottle into restaurants and dance halls and order setups, which consisted of ice and a mixer. Although beer was available by the glass, bringing your own bottle was the only legal way to drink hard liquor in a public place. Those days weren’t so long ago, but they belong to a different era. The coming of liquor by the drink changed the social climate of Texas more profoundly than any other event of the seventies.

Liquor has been a hot topic in the state since the mid-nineteenth century, when temperance forces first began their battle against the bottle. Texas drinkers managed to hold out over the drys until 1919, when Prohibition settled the issue for a time. Fourteen years later Repeal arrived, and the issue of whether or not to sell liquor by the drink went to the state’s voters. In South Texas, where fun-loving Germans and Mexicans had settled, the people favored the sale of mixed drinks, but they were outvoted by Texans in the northern half of the state, where strict Protestant ethics held sway. Into the state constitution went an amendment specifically forbidding “open saloons,” and each county was given the option of outlawing all liquor sales. Texans in wet counties could stock up in a package store, but purchases were strictly cash and carry. Drinkers in dry counties had to drive to the nearest wet area, where they bought a fifth at the liquor store and then paid 75 cents or a dollar for a setup at the beer hall—almost as much as a complete mixed drink cost in other states.

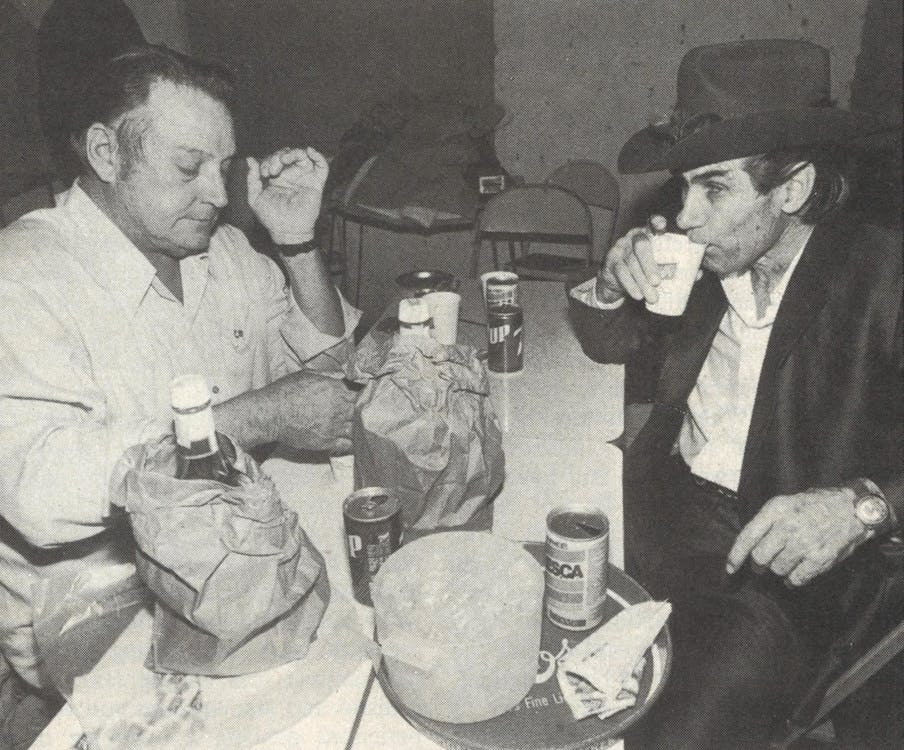

But most Texans didn’t view the situation as a hardship; it was just the way things were, and it was certainly no hindrance to socializing. Author and playwright Larry L. King says of his early years in West Texas: “I lived in Midland, where there was beer but nothing hard. Odessa was wet, though, and there was Pinky’s liquor store just across the county line, only twelve miles away. On Saturday night there were a hell of a lot of cars on old Highway 80 from Midland to Pinky’s. You’d meet half your damn friends there.”

In 1959 the wets got a break with the Supreme Court ruling in Myers v. Martinez, a landmark suit argued by Austin attorney and liquor-law expert Mary Joe Carroll. The decision allowed individual precincts and incorporated cities within a county to vote themselves wet, even if the county itself was dry, and it saved a lot of people a hundred-mile round trip for a night on the town. But it was still liquor by the bottle all across the state until 1961, when the Liquor Control Board (now the Alcoholic Beverage Commission) began licensing private clubs. Technically, members of a club pooled their liquor and paid for it in advance, so all they paid for on the spot was the setups and the service. But in truth, by paying a yearly fee, private club members were getting liquor by the drink. Soon restaurants and motels, most of which maintained private clubs on their premises, latched onto the idea of a temporary membership that allowed guests to belong to the club for a single night. Thus private clubs were essentially open saloons, and their blatant circumvention of the state’s liquor code was what eventually brought liquor by the drink back to the state.

“The hypocrisy of the clubs really got my ire up,” says Joe Christie, former state senator from El Paso and the father of liquor by the drink in Texas. “The only qualification to belong to one was to be warm to the touch.” Then-governor John Connally agreed, calling the private clubs’ procedures a “subterfuge.” Both men also recognized the important boost that mixed drinks would give tourism and business across the state. That point was driven home in 1967, when Connally tried to lure the National Association of Homebuilders’ 50,000-delegate convention to Houston, only to be told there was no way the conventioneers would meet in a state so uncivilized that a man couldn’t even buy a drink.

Says Christie, “John decided then and there that Texas would get liquor by the drink. He gave the convention his promise, and he came back and asked me to take up the fight. I was a freshman senator then, and I felt that the governor was bestowing a great honor on me. I discovered later that he’d asked several other senators and they’d turned him down flat. They weren’t about to take it on.”

No one else thought liquor by the drink had a chance, either. Newspapers routinely ran pessimistic headlines (Long Uphill Fight for Liquor by Drink Indicated). Mary Joe Carroll remembers, “I said, ‘People aren’t going to pay a dollar and a half for what they know is only forty cents’ worth of Scotch.’ I was wrong.” Fletcher Boone, co-owner of the Raw Deal, a popular Austin watering hole, says, “I wouldn’t say that I’d vote against liquor by the drink today—I’m enjoying it, and so is my business—but I wasn’t in favor of it then. I didn’t care what New Yorkers said about us, and if it kept them and Californians from using this state as a tourist spot, good!” But the biggest obstacle of all was that drinking was still seen as a moral issue, the way it always had been. Legislators simply weren’t willing to risk incurring their constituents’ wrath, and so early efforts to pass liquor by the drink in the Legislature bombed. One embarrassing attempt was the mini-bottle bill, which would have permitted bartenders to open a jigger-size bottle, like those served on airlines, for each drink. “That almost got us laughed out of the Legislature,” Christie says. “Pretty soon I got tired of getting my tail beat, and I decided that to get liquor by the drink we’d have to change the constitution.”

Then the fur really began to fly. Churches leapt into the fray, taking the term “demon rum” out of mothballs. A coalition of Baptist preachers ran dramatic ads warning, “Think, Mr. and Mrs. Texan! Which is more important, money or people?” and stressing the huge increase in highway deaths, alcoholism, and divorce that, they said, liquor by the drink would bring. Christie himself came under attack. “Fortunately,” he says, “I had been a strong law and order candidate from the beginning, and I passed some strict law enforcement measures—one against drunken driving, as a matter of fact. So the drys couldn’t paint me as a loudmouthed drunk.

“The election was in November 1970, and the first votes to come in were from Dallas, Fort Worth, Wichita Falls—everything north of Waco. It looked bad. The reporters were calling and saying, ‘Senator, are you going to concede?’ I said, ‘Let’s wait till Harris and Bexar and the rest of the South Texas counties are in.’ It was close, but we won it. And look—now even Waco and Abilene and Irving are wet.”

Liquor by the drink became law in April 1971, and its impact has been measurable and considerable. Highway deaths rose, from 3560 in 1970 to 4424 in 1980, but since Texas’ population grew from 11 million to 14 million in that time, the death rate barely increased. The number of alcoholics, on the other hand went from 425,076 in 1970 to 788,277 five years later, according to the Texas Commission on Alcoholism. The revenue generated by mixed drinks is staggering: in fiscal year 1981 alone, permit fees and taxes on liquor totaled $248 million, compared to a piddling $58 million in 1970. Liquor by the drink has brought in inestimable tourist and business dollars. The National Association of Homebuilders, for instance, whose reluctance to convene in Texas prompted Connally to take up the banner, has already met here eight times and is scheduled to return six times in the eighties, bringing with it some $22 million on each visit.

Liquor by the drink has changed the drinking habits of Texans radically, particularly the type of liquor they choose. “Before liquor by the drink,” Mary Joe Carroll recalls, “you ordered a setup—Coke or ginger ale—and poured in your Scotch or bourbon. Maybe someone drank gin, but that was about it. No one ever drank vodka, much less anything more exotic.” Todd’s in Houston, one of the city’s biggest bars, claims its most frequently ordered drink is the basic Scotch and water, but the Filling Station in Dallas names as number one the piña colada, which was unheard of ten years ago. The beverage that has shown the greatest increase in consumption is wine: Texans drank up 3 million cases in 1971 and 6.5 million cases in 1981.

Of course, the omnipresence of white wine and piña coladas is merely an indication of the urban sophistication—or, some would say, homogenization—that followed close behind the legalization of liquor by the drink. Eleven years ago there were few fancy places to eat in the state and no bars; now elegant restaurants vie with steakhouses for the dining-out dollar. Liquor by the drink has meant more to businessmen than merely the availability of a quick one on the way home: several Northern companies—including American Airlines and Diamond Shamrock—have transferred their headquarters to Texas in the last few years. That would have been unthinkable in the sixties because a dry state, even one with a hefty population, was completely outside the sophisticated corporate world. Liquor by the drink moved Texas into the twentieth century.

Nevertheless, 74 Texas counties remain totally dry. If you find yourself driving down the wrong highway when an urge to wet your whistle strikes, you might as well forget it. If, for example, you head east from Muleshoe on U.S. Highway 70, you can go 216 miles to Vernon and never see a bar. If you turn south on U.S. 283 and drive to Albany, 110 miles along, then east for a couple of hundred miles to Seminole on U.S. 180, and finally north on Texas Highway 214 back to Muleshoe, 110 miles away, you’ll never even sight a swizzle stick. In Ochiltree County you’re closer to Oklahoma bars than Texas booze, and in Gaines County it’s quicker to drive into New Mexico than to reach the nearest Texas bar.

Some dry counties aren’t that bad. You can keep liquor at home, even if you can’t buy it in your hometown, and in a good-sized place like Plainview, in the dry county of Hale, you can still get a drink in a private club. “We’re about the wettest dry county in the state,” says Sheriff Charles Tue. “We’ve got about ninety bootleggers and fifteen private clubs, and if that’s not enough there’s Nazareth [in wet Castro County], twenty-two miles away.” Then again, there are counties like Sterling, where the total population is around one thousand and there’s nary a private club. “It’s pretty quiet around here,” says Sheriff David N. Daniel. “’Course, it’s pretty isolated, too. Sure, it makes a difference that the county’s dry, but if people around here want a night out, they head to San Angelo or Big Spring, same as always. I figure that as far as actual drinking goes, if people want it they are going to get it, one way or another.”

And it’s now easy for Texans to get it, provided they are of legal drinking age—which the legislators had agreeably dropped to eighteen in 1973, once they were over the major hump of legalizing mixed drinks, but which eight years later they raised to nineteen in a fit of concern over teenage drinking. Texas liquor laws are surprisingly liberal as far as the adult drinker is concerned. Texans can drink in public in most places, as long as they don’t become disorderly, and they can drink in their cars, unless they become drunk. Drinking in cars is a luxury few other states permit. In California, for example, a driver can be fined for having an open can of beer in the passenger section of his car.

The 158-page Alcoholic Beverage Code is incredibly detailed and bewildering to the uninitiated, and a lot of misconceptions about it remain. Nearly everyone, including many retailers, thinks it’s against state law to have a bottle of liquor in public unless it’s decently clad in a paper bag—a belief that just shows the moral issue hanging in there. “There’s nothing in the code that prohibits carrying a bottle down the street in plain view,” says Mike McKinney, chief of staff at the Alcoholic Beverage Commission (ABC). “But on the other hand, I wouldn’t do it, would you?”

The code does contain some curious rules. For example, lounge cars on trains may not serve wine and beer while passing through a dry county (a rule somewhat difficult to enforce). Minors are barred from entering package stores, but they are free to go into mixed-drink establishments. Package store owners may not hang anything in a store window that will “obstruct the view of the general public,” a law left over from the den-of-iniquity days that now has the modern advantage of discouraging robberies. Adult Texans may make two hundred gallons of wine every year for home use, but they may not distill liquor—moonshine is, as always, illegal (though hardly a problem anymore; last year the ABC closed down only one still). But these days, with a bar on every corner, who needs to brew his own?

- More About:

- Texas History

- Libations

- Larry L. King