This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

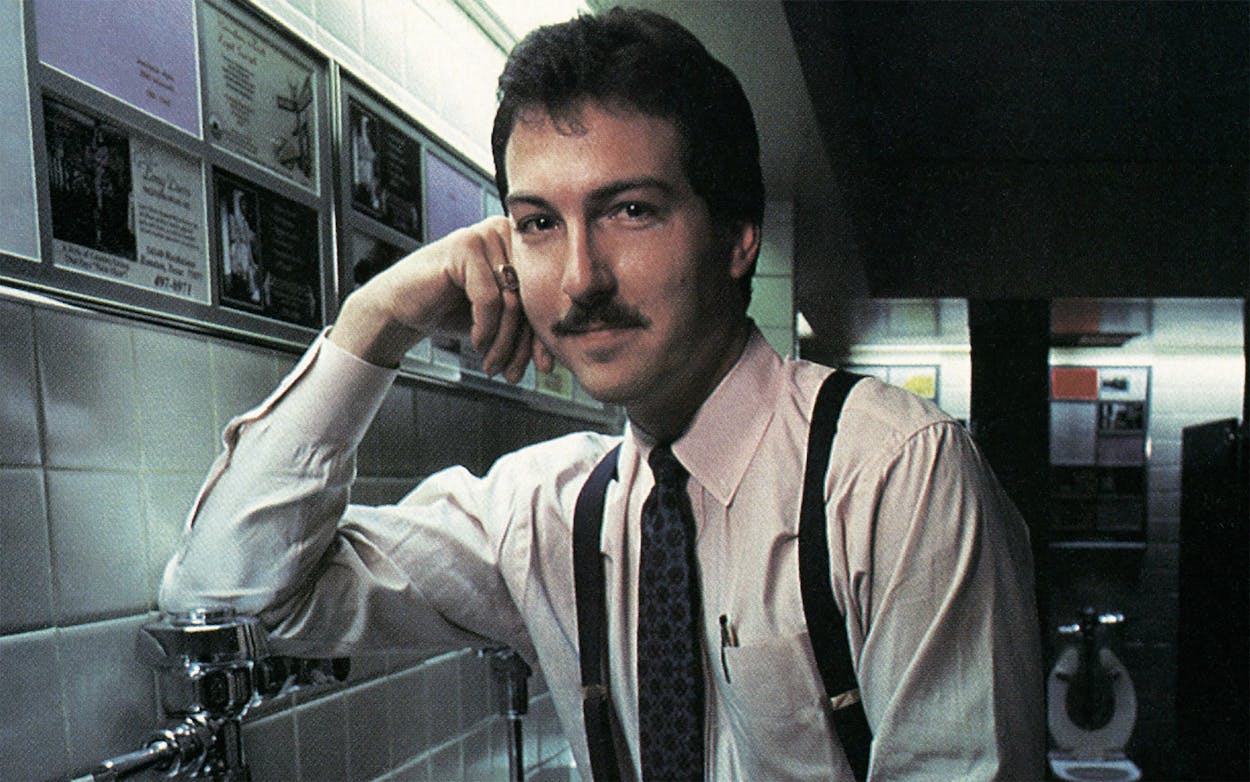

The Whiz

An entrepreneur exploits the ultimate captive audience.

As happens with many men, Mark Evetts had a brilliant idea while standing in the men’s room of a bar, relieving himself of the beers he had just finished drinking. He was in Birraporetti’s, where the front page of the Wall Street Journal is posted above the urinal. Evetts was reading the paper distractedly when a light dawned.

“ ‘Why am I reading this?’ I said to myself. ‘I never read the Wall Street Journal.’ I realized then that I’d read virtually anything they put up there,” he says. “So I figured, why not advertising?”

That was in February 1987. Within eight months Evetts had incorporated Stalltalk and raised $75,000 from private investors who also wondered, Why not? —the question that underlies every great entrepreneurial venture. Today there are 112 boards—fancy-framed advertisements for Chevrolets and health clubs—above urinals in the Summit. Hundreds more are scattered around men’s and ladies’ rooms in Houston bars and restaurants. Evetts’ company, which does business as Headlines USA, received $80,000 worth of new accounts last August alone.

And that’s just in Houston, where twenty people work in the new corporate office. There is also an office in San Jose, California. The company has sold local franchises in Dallas and Fort Worth, in Orange County and San Diego, California; in Atlanta and Macon, Georgia; in Tampa Bay and Orlando, Florida. Evetts is negotiating with the National Basketball Association to put ads in the rest rooms of every sports arena by next season. He has found what advertisers always dream about, a captive audience. And he has found that clever ideas can thrive—even in a bust.

Al Reinert

What the Doctor Ordered

If oil-field valves aren’t selling, try heart-valve gauges.

Everybody talks about diversification. But a small Houston manufacturer named EGC Micromet did something about it. During the boom Micromet produced plastic products for the oil patch: pump and valve parts and electrical housing and outlet boxes used in offshore drilling. After the rig count began to decline, Micromet’s sales plummeted to barely half the previous year’s level. They dropped another 10 percent the following year. The company’s largest customer went 22 months without placing a single order.

The firm cut hours and pay for its 25 employees and started looking for different markets. An obscure new Houston company, Compaq, began ordering plastic parts for the computer it was making. By 1985 Micromet president Rob Myers and his salesmen were calling on semiconductor manufacturers in Massachusetts, California, and New York. Micromet emerged with contracts to make all-Teflon pumps that handle the ultrapure acids needed to make computer chips.

Its next target was the biomedical industry, a natural user of plastics and one of the few sectors of the Houston economy that had money to spend. Among Micromet’s products are a disposable blood-pressure monitor used in open-heart surgery and a set of gauges surgeons use to size heart valves ticketed for replacement.

When the petrochemical industry began to surge in 1987, refineries began to order valves again. But Micromet is a different company today. Its sales are 60 percent above the best boom year, and its work force is up to eighty employees. By January 1 Myers expects to go to around-the-clock operations. Soon he will have to expand his unprepossessing 30,000-square-foot north Houston plant. Five years ago 70 percent of Micromet’s business was petrochemical related. Now 70 percent is nonpetrochemical—products Micromet did not make for customers it did not have five years ago. Vows Myers, “We will never again be dependent on any single industry.”

Tom Curtis

Taking Off

At long last, aerospace manufacturing comes to Houston.

John Mockovciak arrived in Houston in the fall of 1987, but he is exactly the kind of man local boosters were expecting when the Manned Space Center came to town 27 years ago. In their opinion he was long overdue.

Economically speaking, the Houston outpost of America’s space program has always been just that: an outpost. It has provided glamour and prestige, to be sure, and eternal honor—“Houston,” began the first known extraterrestrial call home—but still there has been this lingering bottom-line disappointment. Of the approximately $11 billion spent each year on the space program, most of it was spent elsewhere. Houston owned the heart and soul of the manned space adventure, but the pocketbook remained in Washington, D.C. Hence the yearly tribulations of the Johnson Space Center. The flighty moods of mere politicians determine the center’s strength and morale—to say nothing of its purpose—with predictably erratic effects on the local economy. NASA has been a real drag nearly as often as it has been a big boost.

That isn’t at all what the early enthusiasts had in mind. As the Grumman Corporation’s man in Houston, John Mockovciak isn’t entirely the answer to their dreams—he has his own political problems—but he is a big step in the right direction. He is a symbol that aerospace manufacturing has come to Houston at last.

Nearly all of the major aerospace companies have branch offices in the Houston area. They employ from half a dozen to several hundred people at any given time, depending on what NASA contracts they might be holding and which of those contracts, if any, might be currently funded. But none of the companies does any manufacturing here. Whenever they wangle a contract to build something, they invariably do it “back home,” wherever that may be. That is where the real money goes. Manufacturing implies a local commitment and stability that Houston and the space center have never enjoyed—until this year.

Mockovciak has worked for 38 years for the Grumman Corporation, a company with $2.5 billion in yearly sales headquartered throughout its history in Bethpage, New York, close to the center of Long Island. For half a century Grumman has been the largest supplier of combat aircraft to the U.S. Navy. Mockovciak, who was born and raised on Long Island, was one of the chief designers of the A-6 Intruder, which has been the Navy’s main carrier attack aircraft since the mid-sixties and promises to be around for another two decades. Grumman’s sprawling Bethpage plant has built hundreds of Intruders, providing employment for thousands of workers.

Grumman holds two major NASA subcontracts: one for the crew quarters of the space station and one for an orbital maneuvering vehicle. Both will be built in Houston under Mockovciak’s direction. Last summer Grumman leased and optioned 150 acres at Ellington Field, a decommissioned Air Force base halfway between downtown Houston and the Johnson Space Center. The company intends to build a manufacturing plant on the site as soon as Congress turns loose of the funds already appropriated for the project. Two thousand people should be working there by 1992, unless the politicians get neurotic again. If they do, that could delay the project for a year or two or three. No one can be sure where politicians are concerned.

“We’re literally starting a new business here in Houston,” says Mockovciak. “Grumman isn’t going to leave Long Island, but the high cost of doing business there, that close to New York City, was affecting our ability to be competitive. We just couldn’t attract the talent we need to move into the future.

“The attitude of people here is considerably different than in New York. You can really get things done here. Houston’s a perfect place to build spacecraft. I think some other companies are going to have to come here too, if they want to be able to compete with us.”

A.R.

Glad Scientist

A transplanted Yankee grows rich tinkering in Houston.

For years biologists around the world have been trying to wish into existence a device that can photograph tiny cellular structures without destroying them in the process. The lack of such a tool had been holding back life-science research for decades. Giant corporations and institutions had tried to build such a device but never succeeded.

But John Linner, working in a makeshift basement laboratory in the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, built one. If, as the dream wills it, high technology will one day be as important to Houston as oil, there will have to be a lot more John Linners. Maybe there is hope after all, for in many ways Linner is reminiscent of the archetypal Houston oilmen and developers. He was an outsider lured to Houston by money, uncredentialed for his work yet free to pursue it.

Linner was typical of the high-tech Yankees who arrived in the boomtown days. The Texas Medical Center in the late seventies had grants and endowments to spare, which it used to raid medical faculties across the nation. The University of Massachusetts, for instance, which in 1979 was considered one of the world’s five best teaching hospitals, lost several top staff doctors to Houston in one raid. Linner came from Iowa, where he had a reputation as a brilliant cell biologist. In Houston he developed a passion for margaritas and homestyle chili and a dwindling interest in teaching at the Health Science Center. So he became what he was naturally inclined to be —a basement-lab scientist.

Linner, a huge man (six feet five inches and three hundred pounds) who favors gimme caps and casual clothes, was intrigued with the problem of photographing the tiniest details of cell structure. He had none of the qualifications in engineering or physics that solving it required—but Hugh Roy Cullen didn’t have to be a geologist to find oil. A tolerant dean found the basement storeroom that became Linner’s laboratory. Linner picked up crucial equipment by lurking around loading docks on evenings and weekends, rummaging through dumpsters. He acquired essential knowledge by studying NASA engineering reports. He stayed on the UT payroll and was released from his lectures because his dean believed he was onto something and gambled on him in traditional Houston style. That went on for five years.

“I couldn’t have done it anywhere else,” says Linner. “On the East Coast you’ve got all these committees and red tape, everybody worrying about whose grant category you fit under. On the West Coast it’s all reputation and whose career are you going to step on. None of that really matters around here. In Texas you can go in and talk man to man with your dean and make something happen. They listen to crazy ideas around here.”

In 1986 Linner unveiled the prototype of a device he called the Molecular Distillation Dryer. It was held together with rubber bands and duct tape and relied on a K-mart hair dryer as a key drying element. It nonetheless created a vacuum equal to outer space while producing supercold flashes (minus 320.8 degrees Fahrenheit). The device was essentially a freeze-dry machine the likes of which hadn’t been seen before. Most important, though, Linner’s machine yielded photomicrographs of fine cell structures that until then had been visualized only in theory.

It was the long-sought tool that the biological sciences had been clamoring for. The National Institute of Health—the Pentagon of medical research—ordered one immediately. Other requests poured in even before Linner’s results were published. It quickly became obvious that his patents were worth millions.

The University of Texas, which owns those patents, approved the formation of a private company to make and sell the device and did research on further applications. More than $5 million was raised practically overnight to fund a company and to build a new above-ground laboratory for John Linner. The corporation, called Lifecell, is one of a dozen or so companies spun off from the Texas Medical Center in the past four or five years. They are collectively capitalized at nearly $100 million, and they are all growing fast.

John Linner, newly rich, went out and bought a big fancy luxury car and then sold it and got an even fancier one. “I love it here,” he says. “Houston is where it’s happening.”

A.R.

Gambling on Gambling

A union boss turns bingo king.

It isn’t glamorous and it isn’t high tech, but Chuck Bertani isn’t complaining. Just as the high priests of diversification advise, the onetime union boss took a gamble when times got rough. His chosen new profession: bingo entrepreneur.

In July 1983, as the president of the local machinists union, Bertani saw its membership plunge from a peak of 4,300 toward its current low of 700. His $14-per-hour machinists turned into $3.35-an-hour hamburger flippers when the oil economy soured. For fourteen years Bertani had run bingo games at local union halls, “when it wasn’t legal, so to speak,” he says. He knew that in 1981 Texas voters had authorized nonprofit groups to run bingo games. Better than most people, Bertani understood that the organizations allowed to hold games (groups like the Texas Paralyzed Veterans and the Texas Wheelchair Bowling Association) needed somebody to run them—someone who understood bingo’s money-raising potential, preferably someone who could provide a place to play as well as food and drink. Early in 1984 Bertani opened his first bingo hall, leasing a closed supermarket in northwest Houston and christening it the Family Bingo Center. He rented space to nonprofit groups and handled the food and drink concessions. The money rolled in. He now calls himself a multimillionaire.

In May 1987 Bertani converted a defunct dinner theater into Bingo Wonderland. Bingo, he has found, is virtually a recession-proof business. The poor especially seem eager to risk their last ten bucks—the minimum at Bertani’s halls—on ten $500 jackpots. “Almost everyone in the poverty level plays bingo,” Bertani says. “You can see people bringing out their rolls of pennies and counting out their dimes.”

And so the union leader has become capitalist. One problem he is unlikely to have, however, is labor unrest. Not with eleven well-paid family members working in his enterprise.

T.C.

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Space

- Houston