One morning in mid-April, Scott Sheffield, the chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, one of the largest oil producers in America, seated himself in the wood-paneled boardroom of his company’s headquarters in Irving, gazed into his computer’s camera, and begged a trio of Texas politicians for a lifeline. Over the past two months, oil prices had tanked 60 percent, effectively ending a years-long Texas boom and heralding what many in the industry were calling “the mother of all busts.” As an estimated 30,000 viewers around the world watched online, Sheffield beseeched the three members of the Texas Railroad Commission, the elected body that regulates the state’s oil industry, to limit production, in a bid he hoped would ultimately boost the global price of crude.

Sheffield’s message bordered on heresy. He declared that the same oil revolution that had transformed the United States from petroleum importer to exporter had brought the industry to the brink of financial ruin. “It has been an economic disaster, especially the last ten years,” he said in testimony that had the feel of a key witness turning state’s evidence. “Nobody wants to give us capital because we have all destroyed capital and created economic waste.” If the government didn’t swoop in to save Texas oil producers from their excesses, Sheffield warned, “we will disappear as an industry, like the coal industry.”

It was a stunning admission coming from a man who has done as much as anyone to engineer a geological and geopolitical bonanza, one that now looks like a bubble. But the request for government intervention was also a characteristically strategic play for self-preservation by one of the longest-serving chieftains of the oil business—an industry that, following decades of expansion, now appears on the cusp of a slow, long-term decline.

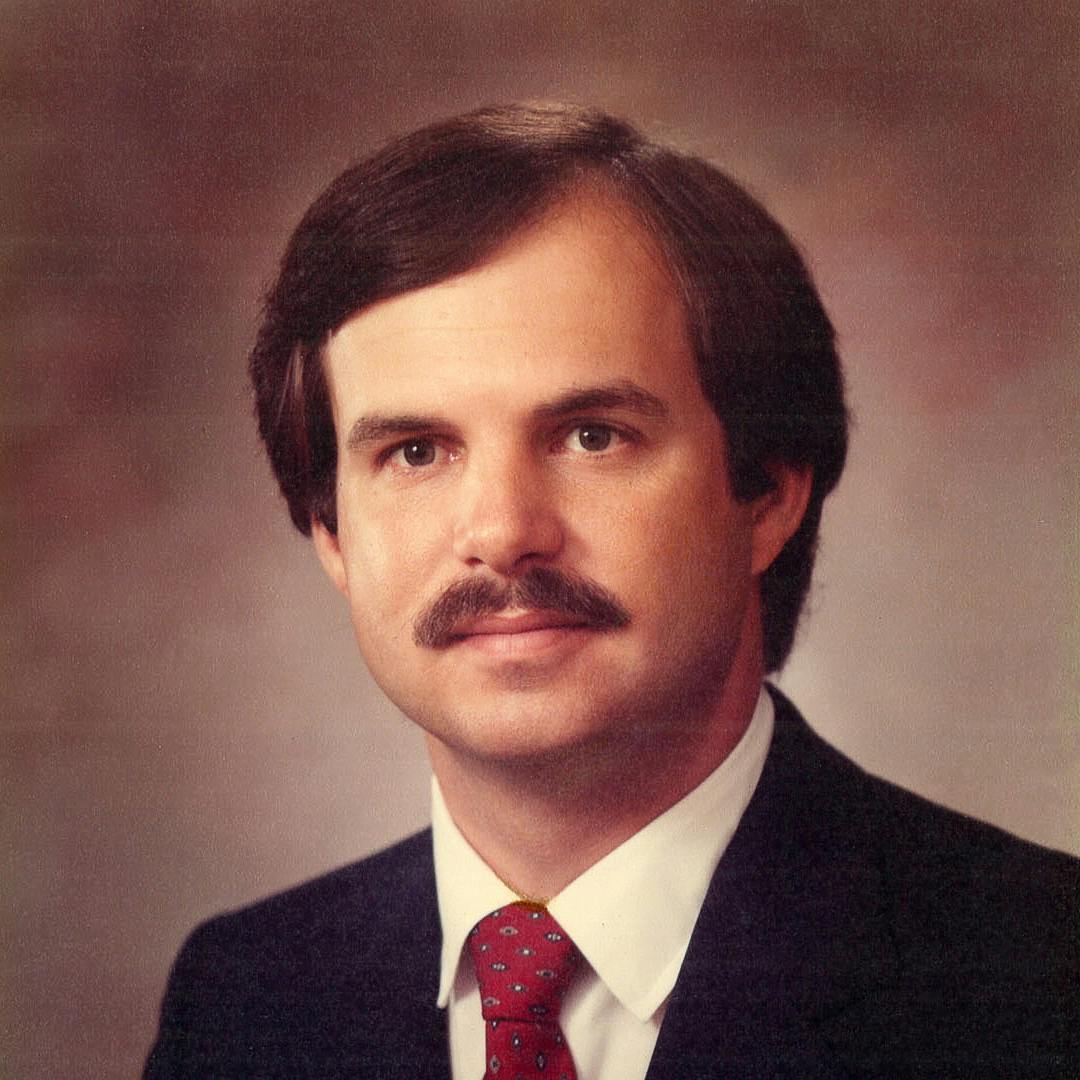

With a love of the limelight, a flair for the dramatic, and an instinct for the jugular, Sheffield, a 68-year-old native of Dallas, has had a hand in the Texas oil sector’s every major swing over the past 45 years: a surge during the oil shocks of the seventies, a falloff throughout the eighties and nineties, and a renaissance starting in the early years of this century as the world sought massively more oil products and Texas unleashed new drilling and fracking technologies to serve up those hydrocarbons. Today, as the oil industry contracts, Sheffield is at the vanguard of a fight for market share, and for survival.

Sheffield took a modest family firm and ballooned it into a publicly traded behemoth—one that, before this spring’s crash, was valued at $26 billion. He did it by pursuing a straightforward strategy: drill, baby, drill. Through Republican and Democratic presidencies, in peace and in war, and to the general delight of investors, Sheffield’s Pioneer pumped up its stock by pumping ever more West Texas crude. Blessed by profitable acreage that Pioneer and its corporate predecessor locked down decades ago, when few others wanted it, and aided by aggressive lobbying in Austin and Washington, D.C., Pioneer grew to become the top driller in the Permian Basin and one of the biggest exploration and production companies in the country. By 2019, the Permian accounted for almost 40 percent of U.S. oil production and fully 5 percent of the global total—an amount nearly equal to the output of Iraq, the world’s sixth-largest producer.

But the Texas boom paralleled other seismic shifts in the international energy market—developments that pose an existential threat to petroleum. Global oil-demand growth has been slowing, and investor concerns over the environmental costs of burning fossil fuels have been increasing. These twin trends have prompted a broadening consensus, even among industry veterans, that oil’s best days are numbered. Yet until recently, Pioneer and most other Texas producers kept cranking out more and more oil—partying like it was 2005.

Now the party’s over. The Texas oil patch and the global energy markets were knocked down this spring by what Sheffield called a “double black swan” event: the simultaneous arrival of a pandemic, which slashed global demand, and a market-share fight between petroleum giants Russia and Saudi Arabia, which flooded more oil into that cratering market. But sober-minded industry insiders see that downturn as far more than another cyclical swoon. They view it as hastening a structural shriveling and consolidation that was already underway—a contraction likely to continue even though oil prices, starting in late April, began to recover. The energy sector’s share of the Standard & Poor’s 500, a key stock index, has tumbled from 29 percent in 1980 to 3 percent as of early June. “The era of rapid growth isn’t going to come back anytime soon”—and probably not at all, said Bob Brackett, a former oil-company executive and now an analyst at asset management firm Sanford Bernstein. “Industries sometimes behave in odd ways as they move toward senescence.”

Oil runs in Sheffield’s blood; restraint doesn’t. Born in 1952, he spent his high school years in Tehran, the Iranian capital, where his father was stationed as a U.S. petroleum executive. When it came time for college, he picked the University of Texas at Austin, intent on becoming a lawyer. But in late 1971, during his sophomore year, he got word that he had flunked out, the result of “too much of everything but studying,” as he recounted in a 2016 speech to the graduates of the UT Cockrell School of Engineering. To shape him up, his father shipped him off for a six-month stint on an offshore drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1973, by which time the young Sheffield had returned from rig duty to campus and switched majors from pre-law to petroleum engineering, two political events occurred that would have a profound impact on his career. That October, OPEC members imposed an oil embargo on the United States and other countries that it saw as supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War, which had broken out earlier that month. By the time the embargo ended, five months later, global oil prices had nearly tripled. To counteract the OPEC stranglehold, Texas called it quits on its own system of oil-price support, one it had employed since the early thirties and that had served as a blueprint for the OPEC cartel. Under the Texas system, called “proration,” Austin had regulated the amount of oil that Texans could pump. With proration gone, Texas oil producers were free to pump at will without the specter of a government cap.

Later, Sheffield would come to find clear lessons in the events of 1973: he would need to master the intricacies of how governments shape oil markets, and he would have to get savvy at bending government to his advantage.

The most immediate lesson, though, was this: The Lone Star State was wide open for a young man to drill.

Sheffield graduated in 1975 and got a job with Amoco in Odessa. Four years later, he became the fifth employee of Parker & Parsley Petroleum, a Midland firm founded by his father-in-law. By 1985, Sheffield was Parker & Parsley’s CEO. In the early 1990s, and then in the mid-2000s, the company bought up oil leases on hundreds of thousands of Permian acres. “We paid nothing,” Sheffield recalled during one of the interviews he and I had this spring.

In 1997 he merged Parker & Parsley with Mesa Petroleum, a Dallas-based company controlled by that even-more-outsized Texas oilman, the late T. Boone Pickens. The goal was a heftier balance sheet, one that would work the “steady Eddie” oil fields in the Permian as a cash machine to help bankroll a hunt for bigger oil troves around the world—the “sexy stuff,” recalled Chris Cheatwood, who hired on as the firm’s exploration manager. The brash new company got a brash new name: Pioneer.

But after several years of exploring abroad, Pioneer returned to its home turf. The move was spurred by the advent of new technologies to coax oil out of shale, a type of rock previously thought too costly to tap. Pioneer bought up acreage in South Texas’s Eagle Ford shale before concluding that the company’s Permian land had an astounding 10 billion barrels of theoretically recoverable oil lurking below. “That,” Cheatwood recalled, “was the aha moment.”

Sheffield raced to assemble the war chest Pioneer would need to unleash modern drilling and fracking beneath its Permian land. The company raised billions from investors in India, in China, and on Wall Street. Between 2010 and 2014, when U.S. oil production jumped 60 percent, to 8.8 million barrels a day, Pioneer more than doubled its oil output, to about 90,000 daily barrels.

Behind the push was Sheffield’s conviction that OPEC would prop up prices, enabling Texas producers such as Pioneer to profitably expand their output. “I’ve followed OPEC closer than almost any CEO in the history of our industry,” he told me. Much of his bullishness “was based on pricing set by OPEC. We made all these decisions based on hundred-dollar oil between 2010 and 2014.”

But the cartel came to feel cornered by the surging U.S. shale industry. In November 2014, with oil prices plummeting, OPEC refused to cut production—an attempt, recalled Brackett, “to drive shale out of business.” Oil prices tanked further. So did Pioneer’s shares.

Sheffield fought back—by seeking government help. Along with other energy executives, he successfully lobbied Congress to lift a longtime ban on U.S. crude exports intended to minimize American dependence on foreign oil. Sheffield argued that in an era of surging Texas oil production, the ban was hurting the country and cutting into the profits of U.S. oil producers.

His bravado rankled some. David Einhorn, a prominent investor “shorting” Pioneer stock—betting the shares would fall—argued at a conference in May 2015 that Pioneer was spending too much for its growth. He dubbed Sheffield “the mother fracker.” Sheffield recalled that epithet gleefully in his 2016 UT graduation speech, asserting that Einhorn had “lost.” (Through a representative, Einhorn declined to comment.)

By the end of 2016, with Pioneer apparently in good financial shape, Sheffield retired. He moved with his wife to Forked Lightning Ranch, a 2,300-acre expanse on the Pecos River near Santa Fe that they had bought the previous year from actress Jane Fonda. The purchase price was undisclosed, but the ranch had been listed for $19.5 million.

Sheffield didn’t get much rest. In February 2019, he returned as CEO, replacing his hand-picked successor, Tim Dove. In late 2018, oil prices had fallen, and so had Pioneer’s stock. Investors were chafing at Pioneer’s rising corporate costs. Ominous clouds were gathering over West Texas.

Before the shale boom began, predictions of “peak oil” had dogged the industry. The notion held that growing demand, particularly in developing countries, would exhaust global supply, sending oil prices soaring and an energy-starved economy cratering. But by the time Sheffield returned from retirement, a consensus was developing about a different sort of oil peak: a maxing out of demand, not supply. Investors were coalescing around a view that while oil would remain in demand for decades—including for the petrochemicals used to make everything from fertilizer to solar panels—growth in oil consumption had already begun to slow and would, perhaps as soon as 2030, enter a gradual, permanent decline. To maintain profitability, oil producers would, much like tobacco companies, have to shift from growing their industry to managing its tail. Companies unable to do so would fail. In October 2018, a few months before Sheffield returned as CEO, Brackett, the analyst, issued a report declaring the oil industry’s dotage. Its title: “Act Your Age.”

One reason for the new bearishness about oil was an unexpected bullishness about electric cars. Once laughed off as baubles, they had begun to erode sales of conventional vehicles in some parts of the world. Sheffield told me that he has come to concur with projections that within two decades electric cars will account for as much as half of all auto sales. He himself has taken to driving an electric ATV around his ranch. “There will be an electric-car revolution,” he told me.

Another reason: profit-hungry institutional investors, which for decades had formed a key part of the oil industry’s shareholder base, increasingly fretted about climate change. They argued that carbon regulations, on top of the rising economic competitiveness of electric cars and of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, would make it difficult to profitably drill much of the petroleum still in the ground. The long-treasured “reserves” that shape oil companies’ valuations, they worried, would instead become “stranded assets.”

In March 2019, the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund, which is based in oil-rich Norway, announced it would divest its holdings in companies focused entirely on pumping more oil and gas. The fund, Pioneer’s seventeenth-largest institutional shareholder, hasn’t yet sold its Pioneer shares, but Sheffield told me that it’s only a matter of time. “There’s definitely a movement by funds around the world to move out of fossil fuels,” he said. “It’s causing less capital to flow into our industry.”

Upon his return last spring, Sheffield began downshifting Pioneer for the tougher road ahead. In late 2016, not long before his brief retirement, he had set an internal target to increase the company’s production by about a factor of eight, to one million barrels a day, over about a decade. While Sheffield was gone, Dove had gone public with that goal. But Sheffield, back as CEO, repudiated those ambitions. Instead, he launched a belt-tightening program that included asset sales, layoffs, and a drastically reduced target for annual oil-production growth. In hindsight, he told me, the industry had “added too much oil in an oversupplied market.” The good times were coming to an end.

Last year, Pioneer moved into its new Irving headquarters. The gleaming, ten-story complex, which the company leases from an investment consortium, features shops, running trails, and fishing ponds. On March 6, a glorious spring day in North Texas, Sheffield was sitting in his top-floor office when the bottom fell out of his world.

That day in Vienna, seven hours ahead of Irving, OPEC and other major oil producers (a group known as OPEC+) held a pivotal meeting. It did not go well. As the coronavirus threatened to stifle global demand for oil, Saudi Arabia and Russia vowed instead to ramp up production in a struggle over market share. West Texas Intermediate, the U.S. brand of crude known as WTI, fell 10 percent, from $46 to $41 a barrel. By the following Monday, it had tumbled another 25 percent, to $31. “I knew at that point in time,” Sheffield recalled, “that oil was going to fall to the mid-teens at least.”

American producers are particularly whipsawed by swings in oil prices. Producing a barrel costs more, on average, in the States than it does in other major oil regions, notably the Middle East. Though U.S. companies vary in their costs, they typically need a WTI price of at least $22 just to avoid losing money on the wells they already operate and as much as $55 to make sufficient returns to drill new ones, according to Brackett, the analyst. By contrast, the Saudi Arabian oil company Aramco can drill profitably with oil prices closer to $10. That’s why Texas is regarded in the global oil market as a “marginal” producer. When prices are high, Texas rocks and rolls. When prices are low, Texas takes it in the gut.

With oil prices in free fall, Sheffield gathered his top executives. They devised a two-front battle plan: shore up Pioneer’s balance sheet immediately, and push the government to boost oil prices longer-term.

Job one: slash drilling while preserving cash flow. On March 16, Pioneer announced it would reduce its planned capital spending for 2020 by 45 percent and halve its number of drilling rigs. But it would trim actual oil production far less: only to 2019 levels, or about 12 percent below the 2020 target it had announced before the crash. To protect itself, Pioneer went to Wall Street and bulked up on financial instruments known as hedges, widely used in the oil industry. Long an aggressive hedger, Pioneer opted for a variety that included a particularly complex type called a “three-way collar.” The effect of its hedges, according to Pioneer, is that the company will receive an average of $40 for each barrel of oil that it expects to produce through the end of the year, as long as Brent crude, an international benchmark oil, stays within a particular price range.

Job two: execute a grand play of political chess intended to reinflate oil prices. Antitrust law in the U.S. bars oil companies from colluding to cut output. “But there are legal ways for the government to tell us to reduce production,” noted Cheatwood, the Pioneer field executive. With OPEC+ having failed to prop up prices amid the Russia-Saudi spat, Sheffield and his deputies decided they’d ask the Texas Railroad Commission to reassert the role it had played until 1973.

On March 30, Pioneer, along with Parsley Energy, an Austin-based oil company founded in 2008 by Sheffield’s son Bryan Sheffield, submitted a request to the commission asking it to reinstate proration, Texas’s old system of production limits. Under Texas law, if “waste” is found to exist in the oil market, the commission must address it. In the thirties, when Texas initiated proration, that waste was physical: some Texans were dumping oil into aboveground pits so their neighbors couldn’t snag it themselves from underground reservoirs. Sheffield and Parsley’s chief executive, Matt Gallagher, argued that another kind of waste—“economic waste,” in which Texas producers were pumping beyond market demand, thus depressing prices—was just as problematic. “If Texas leads the way, maybe we can get OPEC to cut production. Maybe Saudi and Russia will follow. That was our plan,” Sheffield told me. “I was using the tactics of OPEC+ to get a bigger OPEC+ done. Let’s get the price of oil back into the $30s as quickly as possible.”

Sheffield played Washington too. In public statements throughout March and early April, he called on President Trump to pressure OPEC+ to curtail production. On April 12, Easter Sunday, following a weekend in which Trump said he had worked the phones, OPEC+ announced a production cut of 9.7 million barrels a day. Sheffield wasn’t impressed. “He didn’t get enough cuts,” Sheffield told me. The market agreed. By Tuesday, April 14, oil prices had fallen another 12 percent.

That morning brought a corporate fight for the ages. Before the Texas Railroad Commission, a 129-year-old tribunal whose typical deliberations pack all the suspense of a slowly rocking pumpjack, the teetering titans of the Texas oil industry faced off in a session that lasted ten and a half hours. That it occurred over the internet, thanks to the very shelter-in-place rules that had tanked global oil consumption, only added to the drama. At issue: which struggling oil companies would be helped by the state and which would be hobbled.

Sheffield, beaming in from his Irving boardroom, cast himself in the role of truth-teller. He argued that only a government production cap could save an industry that was, with irresponsible abandon, sucking oil from the ground and pouring it into a saturated market. To ensure that any production cut by Texas triggered enough tightening of global oil supply to significantly push up prices, he suggested that the commission predicate proration on cuts by other U.S. states as well as foreign countries.

He dismissed as self-serving blather the argument that many of his competitors had made: that a production cap would violate Texas’s free-market principles. “You have to be joking. After thirty-five years as a CEO, I’ve never seen a free market,” he testified. The big companies “have the worst track record” in financial performance, he said. “They are not efficient, and they are causing economic waste.”

Underlying Sheffield’s argument was a question of corporate financial discipline. Some Texas oil producers took on more debt than others to finance their expansions. Pioneer, largely because it had gotten its Permian acreage years ago, when it was cheap, needed to borrow relatively less than rivals that had ramped up in the Permian during frothier times. So Sheffield’s call for Texas proration played to his competitive advantage: Pioneer was better positioned to ride out a potential across-the-board production cut than what Sheffield called his “way-overleveraged” competitors.

Sheffield’s rivals argued that he was just trying to get an edge. “When a vocal minority takes a position in favor of artificial market manipulation that is so far removed from the consensus of a vast majority of operators, one can only surmise that their motives and objectives are primarily company-specific as opposed to broadly industry-supportive,” said Lee Tillman, the CEO of Marathon Oil, which since mid-February had lost 63 percent of its market value.

Other critics of Sheffield’s suggested that he wanted regulators to shield him from his own gambles. They pointed out that contracts with landowners and pipeline operators typically obligate producers to pump and ship a minimum amount of oil or pay a penalty. But the contracts also usually have provisions that release producers from those obligations in the event of external factors, such as government orders. Jim Teague, co-CEO of Enterprise Products Partners, a Houston-based company that operates pipelines and oil-storage facilities, suggested, without naming Sheffield, that the Pioneer CEO and other proration supporters were seeking the commission’s help “to get out of some of their obligations.” (Texas Monthly is owned by the chairman of Enterprise Products Partners and maintains editorial independence from that company.)

Sheffield had vocal support from other Permian oil companies. Without government action to buoy prices, “we’ll see record bankruptcies” in Texas, said Wil VanLoh, the CEO of Houston-based Quantum Energy Partners. The other large players were naive to think that the oil market would recover this time as it had in prior downturns, he said. “I sense a tone deafness to what is really happening in the world of energy right now.”

In the wake of the meeting, oil prices fell even further. On April 20, briefly but astonishingly, they turned negative. Two weeks later, on May 5, the Railroad Commission voted two to one not to hold a hearing on cutting production, effectively dismissing Sheffield’s proration request.

A few days before that denouement, Sheffield and I spoke. Since early January, the market had erased about $11.5 billion, or more than 40 percent, of Pioneer’s value. Like much of humanity, Sheffield had been rendered homebound. Unlike much of humanity, he was holing up in luxury. Over Zoom, I saw the vaulted ceiling of his hacienda-style New Mexico ranch house towering above him. His head was covered in a nest of gray hair that, he noted apologetically, hadn’t been trimmed in ten weeks. Alone at his computer, the man looked more the rumpled grandfather of eleven than the hard-charging oil CEO whose compensation totaled $13.4 million last year. He noted that of the six oil downturns he has survived in his more than four decades in the oil business, half have come in just the past eleven years. “The world is getting more volatile,” he said.

Sheffield sketched a restrained future for Pioneer. It will be operating in a slow-growing or shrinking industry, as electric-car sales surge and investor concerns about climate change mount, putting more and more pressure on companies to spin off cash rather than boost production. “I don’t think the industry will ever get back to where they were before the crisis,” Sheffield said.

In May, Pioneer disclosed its first-quarter results. Profits were down 17 percent. Spending on drilling and other capital expenses would fall even further than the company had told investors two months earlier. Unlike companies shutting down most of their production, Pioneer, leaning on its hedges, was turning off only a relative handful of its wells. But it was still pulling back, saying that it planned to produce slightly less than the average 211,000 barrels per day that it sold last year.

By early June, oil prices and oil-company stocks, including Pioneer’s, had recovered somewhat. Along with many Texas producers, OPEC+ had continued dialing back production. But the underlying forces threatening the industry long before this spring’s crash continued unabated. “We’re not out of the woods yet,” said Sheffield, who by then had gotten a haircut. Although Pioneer wasn’t trying to get out of any pipeline or pumping contracts, he said, it was exploring whether to sublease portions of its partially empty headquarters. After years of relentless growth, the biggest driller in the biggest basin in the biggest economy on the planet had a new plan for corporate success: easy does it.

Jeffrey Ball, previously an editor and reporter in the Wall Street Journal’s Dallas Bureau, has written for such publications as Fortune, Mother Jones, and Foreign Affairs.

This article originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- Business

- Longreads