The new tax bills that have recently passed the U.S. House and Senate are not an easy read—for senators or for the average taxpayer. (The Senate bill alone is 479 pages.) And hardly anyone seems to know what the final version will look like once the two congressional houses vote to reconcile the two different versions of it.

That uncertainty extends to the energy industry—the bills outline provisions that could impact both the oil and gas and renewable energy industries.

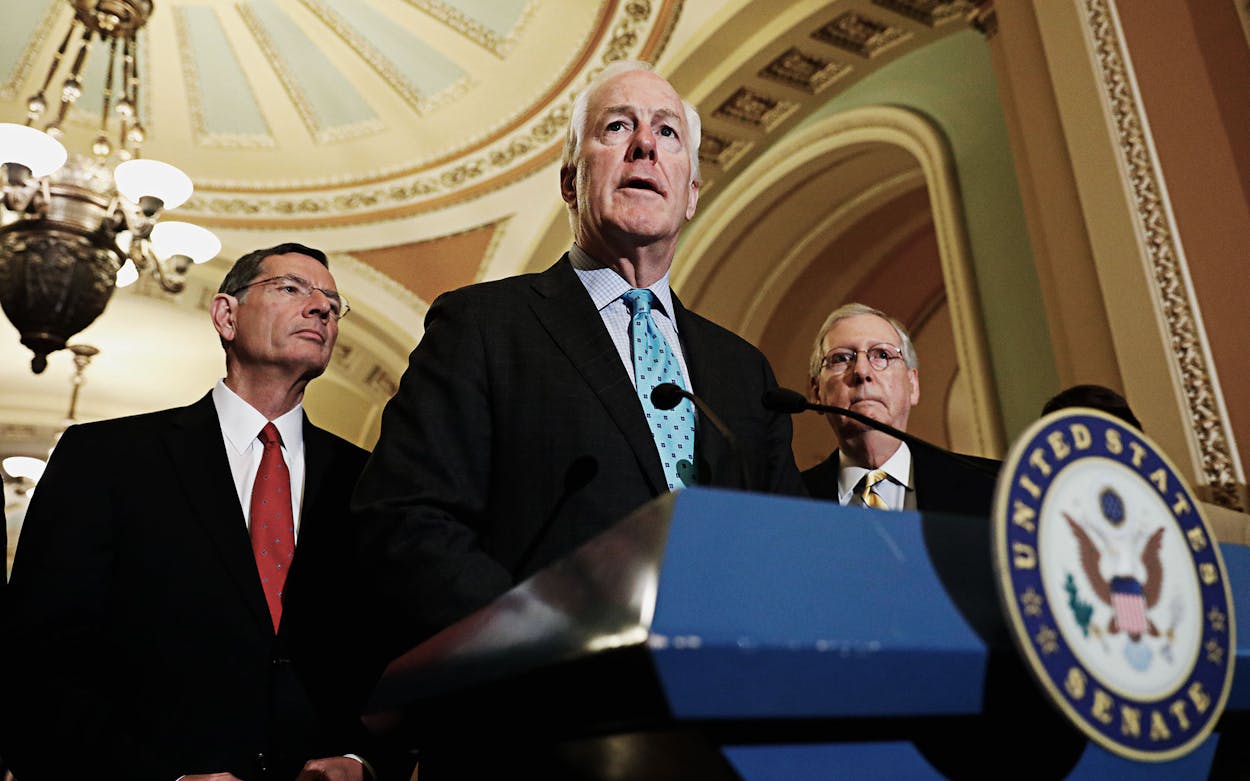

Texas senator John Cornyn added a last-minute amendment to the Senate bill that would effectively allow oil and gas companies classified as “master limited partnerships,” a type of publicly traded partnership, to “pass through” income to their investors.

“A corporation is taxed on its income, and that income is distributed to its shareholders as a dividend, and that dividend is taxed again,” explains Chauncey Lane, a Dallas-based lawyer in the energy sector. Essentially, profits from a regular publicly traded partnership have a “double taxation.” Master limited partnerships, or MLPs, which are mostly oil and gas extraction industries, avoid the double taxation, says Lane. “The income flows through [the MLP] and and is only taxed once it is delivered to investors or owners,” he says.

The pass-through provision generally supposed to help small businesses, but most publicly traded partnerships are “are no one’s idea of small business,” says John Gamino, the director of the accounting program at UT Dallas’s Naveen Jindal School of Management. Since they are publicly traded entities, these companies draw from a large pool of investors and capital.

“Under current law, publicly traded master limited partnerships (MLPS) are taxed as pass-through entities, and this amendment simply preserves that status in the new bill,” says a spokesperson from Senator Cornyn’s office. According to the Wall Street Journal, Cornyn’s amendment carved out a provision for the oil and gas industry’s MLPs, which might have been blocked from a lower pass-through rate otherwise.

Gamino says that the amendment—and the existing tax structure—ensures that “the actual tax-dollar benefit [goes] to the partners or investors.” The partners in these companies pay lower tax rates on their investments, therefore making the company itself more attractive as an investment.

“Senator Cornyn’s amendment aims to benefit investors in two ways,” he says: there’s a year-to-year deduction that partners could use on their own tax returns, and the amendment would also reduce the tax rate if an investor makes a profit by exiting the investment altogether. “Combining them is as good as it gets, short of a flat-out tax exemption,” says Gamino.

While Cornyn’s amendment could help the oil and gas industry attract investors, provisions in the House versions of the tax bill could make it that much harder for wind companies in the state to do the same. The bill disrupts a planned phaseout of the production tax credit, which has been a primary driver of investment in wind power. The wind industry is advocating that the phaseout stays intact.

“The wind industry has been preparing for those credits to go away, and they’ve been able to work that into long-range planning,” says Joshua Rhodes, a postdoctoral researcher at UT Austin’s Energy Institute.

It might takes years to plan a wind farm, says Rhodes—everything from land rights to transmission connections—even though the construction of a large project can take less than a year and a half. “When you have multiple years to deal with in getting projects off the ground, having multi-year certainty on what your tax structure is going to be, and the rebates and incentives, can help you get the deals to go and build the [project],” he says.

The renewable energy industry might take another hit in tax equity investments and even foreign investments if the Senate and House bills’ provisions make it to the final version. Tax equity investing allows investors to trade tax credits likes the wind and solar production tax credits. “If those tax credits go away, then the tax equity market dries up as well,” says Lane. “Investors have less incentive—in fact, they probably will not invest in renewable energy projects if they lose that tax credit.”

The Senate’s Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax, which is aimed at preventing companies from evading domestic tax liabilities, might turn away foreign investment in renewable energy, says Lane. Clean energy industry leaders have publicly expressed concern about the impacts of the tax on wind and solar industries, which they say generates $50 billion annually in U.S. investment.

Even without the BEAT provision, says Lane, the other factors already in the bill could cause investments in wind and solar to drop. “To the extent that investing in U.S. renewable energy projects becomes less attractive domestically, it’s equally less attractive for foreign investors.”

- More About:

- Energy

- Wind Power