It was one of the finest marketing slogans ever hatched from the mind of man, a simple, unmistakable declaration of pride and resolve: “Long live long necks.” Fittingly, it seemed to just float into view, conceived over cold Lone Stars in the parking lot of Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters sometime in early 1974.

Jim Franklin, the concert hall’s wild-eyed resident artist and occasional master of ceremonies, was unwinding not far from the backstage apartment he shared with a boa constrictor and a chicken. His conferee was Jerry Retzloff, Lone Star’s local district manager, and talk had turned to the beer business. Retzloff was a reluctant newcomer to Austin, having been abruptly transferred from the brewery’s San Antonio headquarters the previous summer. Budweiser had started taking huge bites out of Lone Star’s Austin sales, in large part by targeting college kids. Retzloff knew that Lone Star president Harry Jersig, a first-generation German Texan and beer man of the old school, was unwilling to court the youth market. Their long hair sat ill with Jersig’s buttoned-up sensibility, and he didn’t want to appear to encourage underage drinking. And even if Jersig eased up, Retzloff would still have Lone Star’s long-standing image to contend with. Its slogan at the time, as voiced in commercials by Ricardo Montalbán, was “The Beer From the Big Country.” It was a rural, outdoorsman’s beverage, a beer for cattle pens, deer blinds, and bass boats.

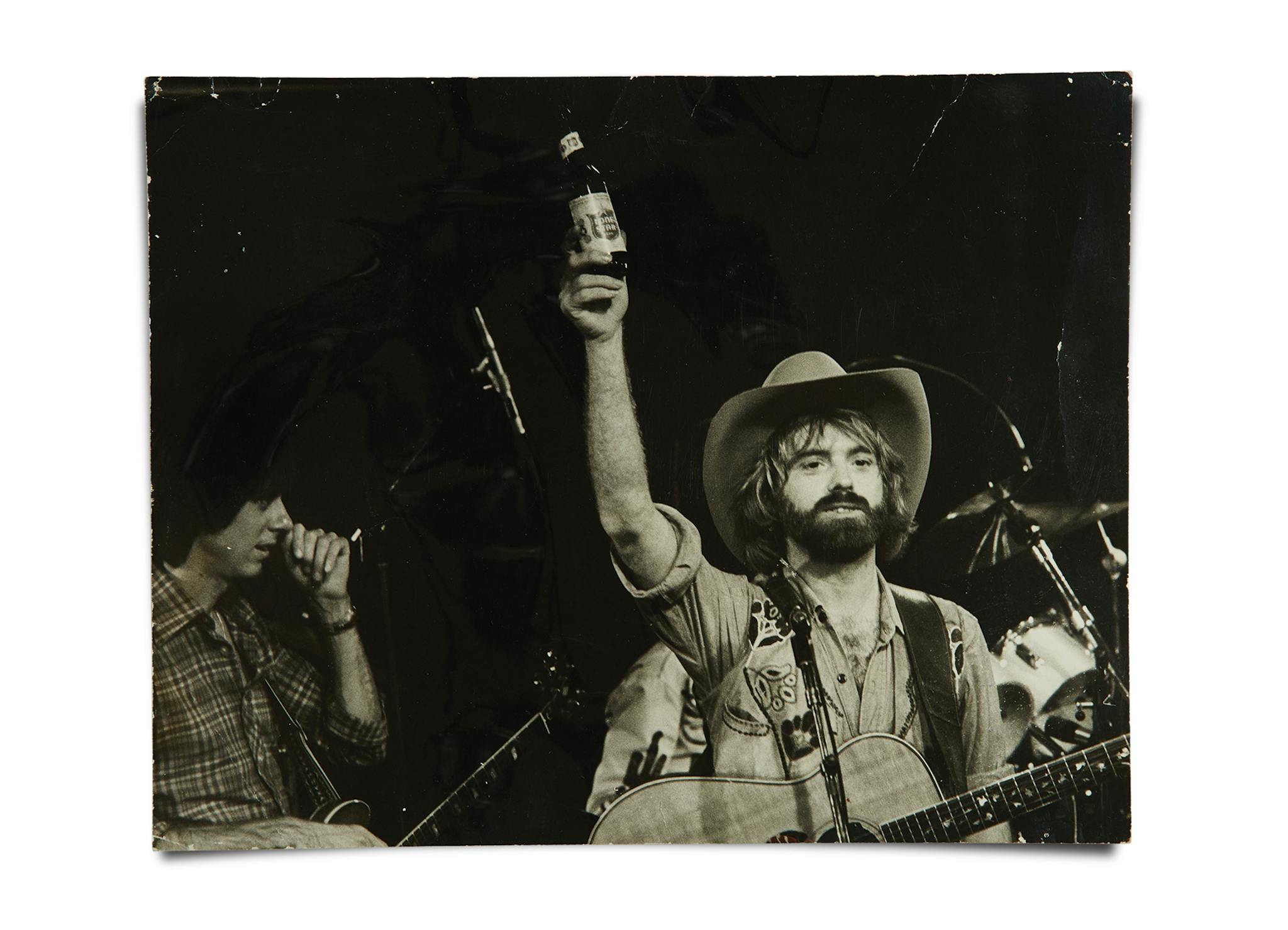

But when Retzloff arrived in Austin, he saw a surefire new angle emerging. He spent his days cultivating relationships with the distributors who brought Lone Star to town and the bartenders who sold it. His nights, however, were spent listening to music in the city’s budding progressive country scene, and he noticed an ungodly amount of Lone Star being drunk at its epicenter, the Armadillo. A check of the books at the brewery confirmed his impression: more Lone Star draft beer was sold at the ’Dillo, capacity 1,500, than any venue in the state except the 44,500-seat Astrodome. Whether it was a Texas nativism that even a hippie couldn’t shake or some precursor to modern-day hipster irony, the longhairs were threatening to make the cowboy beer their own.

Retzloff persuaded his superiors to let him pursue them. He brought the vice president of marketing, a thick-necked Canadian named Barry Sullivan, to the ’Dillo to hear the scene’s golden boy, Michael Murphey. When Murphey opened the second verse of his anthem, “Cosmic Cowboy, Pt. 1,” by singing, “Lone Star sipping and skinny-dipping,” every hippie in the room raised a Lone Star toward the rafters and screamed. Sullivan was sold.

Then Retzloff went to work on Jersig, who’d instructed him to grow Austin sales by 15 percent in the coming year. “I went back to Mr. Jersig and said, ‘How about I give you thirty percent?’ ” recalls Retzloff, now 74. “ ‘But you’ve got to let me do it my way. I’ve got to get rid of this coat and tie and get me some cutoff shorts and grow a beard’ ”—all of which were forbidden by strict Jersig policy—“ ‘because I can’t sell beer to these kids that way. I’m in there moving kegs around in a tie? They think I’m a narc! I’ve got to become part of the in-crowd.’ ” Jersig acquiesced—and let Retzloff know his job was on the line.

So Retzloff started thinking about a strategy, and that’s what he was doing, out loud, with Franklin in the ’Dillo parking lot. In his ten years with Lone Star, he’d worked in the plant, the front office, and the field, and he knew that to prod a meaningful uptick in sales, he’d need something to promote other than the beer itself, something that made it seem new. He remembered the Handy Keg, a twelve-ounce can painted to look like a keg that had helped Lone Star to its first year of more than a million barrels sold, in 1965. He looked at the bottle in his hand. It was skinny, with an extended neck, which in the industry was known as a returnable, as opposed to the stubbier bottles that drinkers could throw away. Budweiser didn’t push those longer bottles in Austin because it was too costly to ship them back and forth for refilling.

Studying the bottle, Retzloff recalled a recent sales visit to a bar in Dallas, where he’d bought returnables for some SMU sorority girls. “Oh, look,” one had gushed. “Longnecks! Just like we get when we go down to Luckenbach.” Her excitement surprised him, and so did her description. “Longneck” was a term he’d heard only in a few small South Texas towns. He kept thinking. “Something about those returnables had always stuck in my head,” he says. “When I worked in the plant, our first beer break was usually at nine a.m., and we had about five places around the brewery where we could drink free beer. It’d be either in cans, returnables, or snub-nosed disposables. For some reason, the employees would always call around and see which spot had returnables, then go take their break there. I also knew, from my time in the accounting office, that eighty percent of the beer that employees took home was returnables.

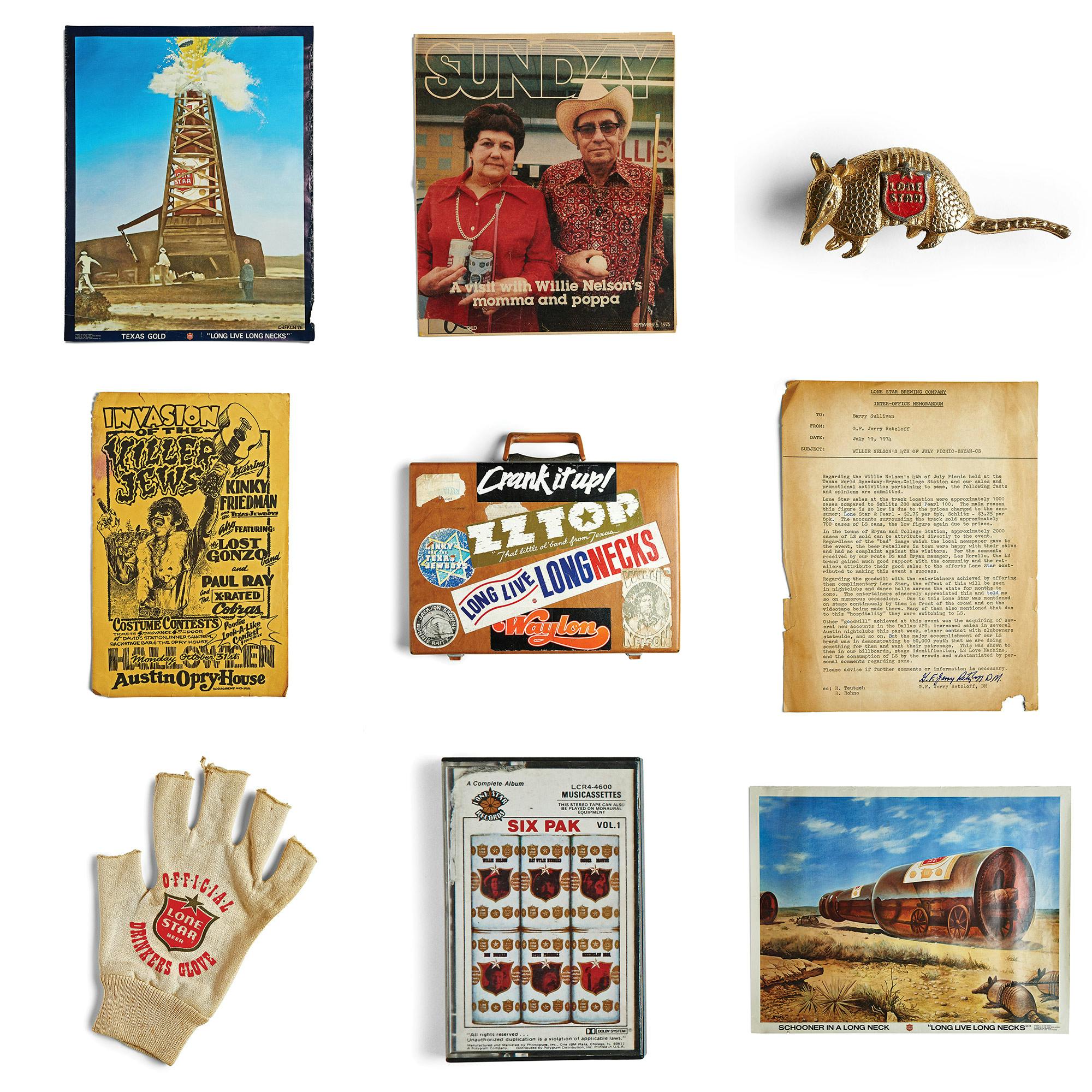

“So I told all this to Franklin. I said, ‘These are beer people. They don’t give a darn if you come out with cans that fit in your back pocket, socks, purse, or whatever. They will forever be drinking returnables.’ ” That was all Franklin needed. His wonderfully warped mind had already made the lowly armadillo the mascot of the Austin counterculture, and he went to work on a poster design that would similarly elevate Lone Star. “Do you remember that first poster?” says Retzloff. “The atom bomb had just hit and blown everything off the landscape. The only two things still standing, the things that were absolutely invincible, were the armadillo and the Lone Star. And then he came up with that slogan: ‘Long live long necks.’ ”

This was a campaign that would march. Lone Star paid Franklin $1,000 for that first poster and asked him to design three more. A “consulting firm” made up of ’Dillo employees and patrons who were working with Sullivan on hippie-friendly radio ads designed “Long Live Long Necks” bumper stickers, modeling them after the über-patriotic “America: Love It or Leave It!” stickers that rednecks and reactionaries affixed to their pickups. And Retzloff became Jersig’s unofficial liaison to the music world, the guarantor that Lone Star would be the on- and offstage beer of every act passing through Austin.

The efforts paid off beautifully. In 1975 Lone Star turned around five years of declining sales. The increase was only 2 percent statewide, but it owed entirely to a 46 percent jump in Austin. And as the Austin music scene started to gain wider attention, as the ’Dillo became a nationally known venue and its cosmic cowboys morphed into Nashville’s country outlaws, Lone Star’s profile rose with it. Now a beer drinker could order a “longneck” anywhere in the state, and a bartender would know he wanted only one thing. Slowly but surely, Lone Star, which was available exclusively in Texas and a few scattered juke joints in western Louisiana, was becoming the coolest beer in the United States.

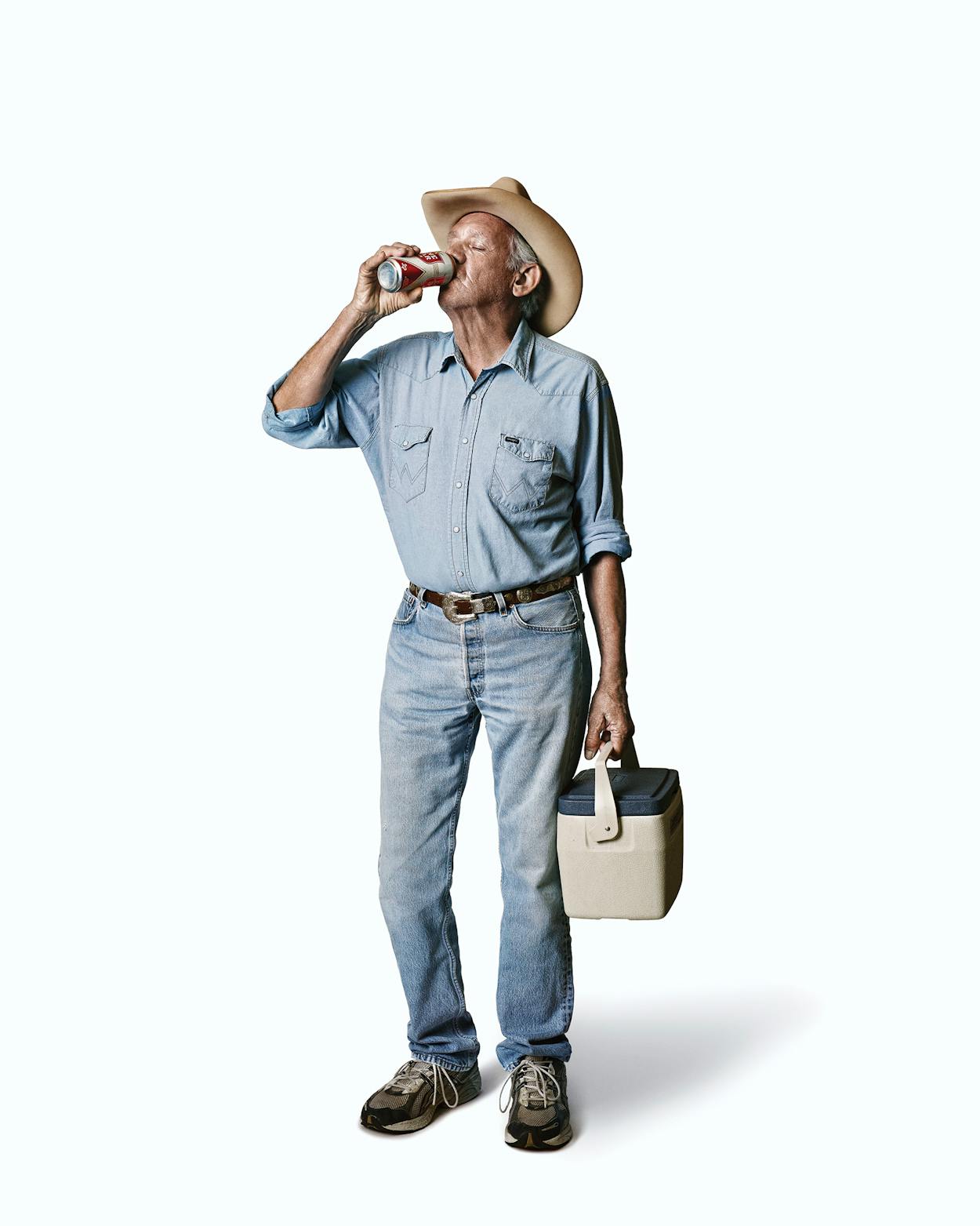

Jerry Retzloff loves Lone Star. Not with a salesman’s puffed-up affect but with a genuine, abiding passion that runs so deep he sometimes seems to believe it’s contagious. I met him two years ago when I was working on a story about the evolution of so-called outlaw country music. We talked over the phone about the Armadillo days, and I happened to mention I’d be interviewing Willie Nelson later in the week. “Cool,” he said. “Just tell me when and where, and I’ll be there.” Huh? That wasn’t part of my plan, and I politely declined. But clearly his old connections were still intact, because when I showed up in Luck a few days later, there they were: Willie, Jerry, and a cooler full of Lone Star.

And that’s Jerry Retzloff. Few are the occasions he’d deem inappropriate for breaking out a six-pack of what he calls “canned goods,” even if he’s not necessarily invited. Note, though, that he’s not just a beer drinker and certainly not a drunk. He’s a Lone Star man. And more than the silver hair poking out from under his ball cap, more than the week’s worth of white stubble typically seasoning his cheeks, even more than his snap-button denim work shirts that appear to date back to his first nights trying to fit in at the ’Dillo, the thing that pegs him to a bygone era is his absolute allegiance to his brand of beer. Ask him simply, “Why Lone Star?” and he’ll fire back with a logic as obvious to him as gravity’s pull: “That was Daddy’s beer.”

When he talks about his life, every key event has a Lone Star somewhere in the frame. “I was born the same year as the brewery,” he begins. “I came in January 1940, and it came in April.” He grew up just four miles from the plant in San Antonio, where his dad had a radio repair business, but he spent summers in Port Aransas, where his dad owned party boats and a bar on the beach. Jersig would rent his dad’s boats to fish tarpon, and young Jerry would cut bait for him. In the fifties, Jerry’s older brother liked to go swimming in a pool Jersig built at the brewery, but Jerry preferred listening to blues in San Antonio’s black nightclubs. “I always had a quart of Lone Star between my legs when I headed out at night in my ’46 Ford.” After one short year in college, he spent two long years in the Coast Guard Reserve in San Francisco—“All my friends sent me Lone Star labels and bottle caps; it made me homesick”—and then came back to San Antonio, where he soon met a girl. “I was a confirmed bachelor when I met Sally, but she could outdrink me on Lone Star. Our first date was to some guy’s house, and we ended up doing that hula-hoop dance, the twist, on the roof. It took me a year to finally get a job at the brewery to make enough money to marry her.”

That job was in the accounting office, and it started in 1963. The beer business was still largely a regional concern, which explained Jersig’s swimming pool, as well as the picnic grounds, well-stocked catfish tank, and museum he opened near it. A local product needed to matter to its community, and Lone Star did. In those years, it was the top seller in San Antonio, Austin, and South Texas, while Pearl owned Dallas and Houston. But by the end of the sixties, breweries with a longer reach were moving in, chiefly Schlitz and Bud. Retz-loff was one of the guys handpicked by Jersig to rise through the ranks in that era. Armed with a marketing degree from St. Mary’s University that Lone Star had paid for, Retzloff went out into the field, first working points west of San Antonio, and then Austin.

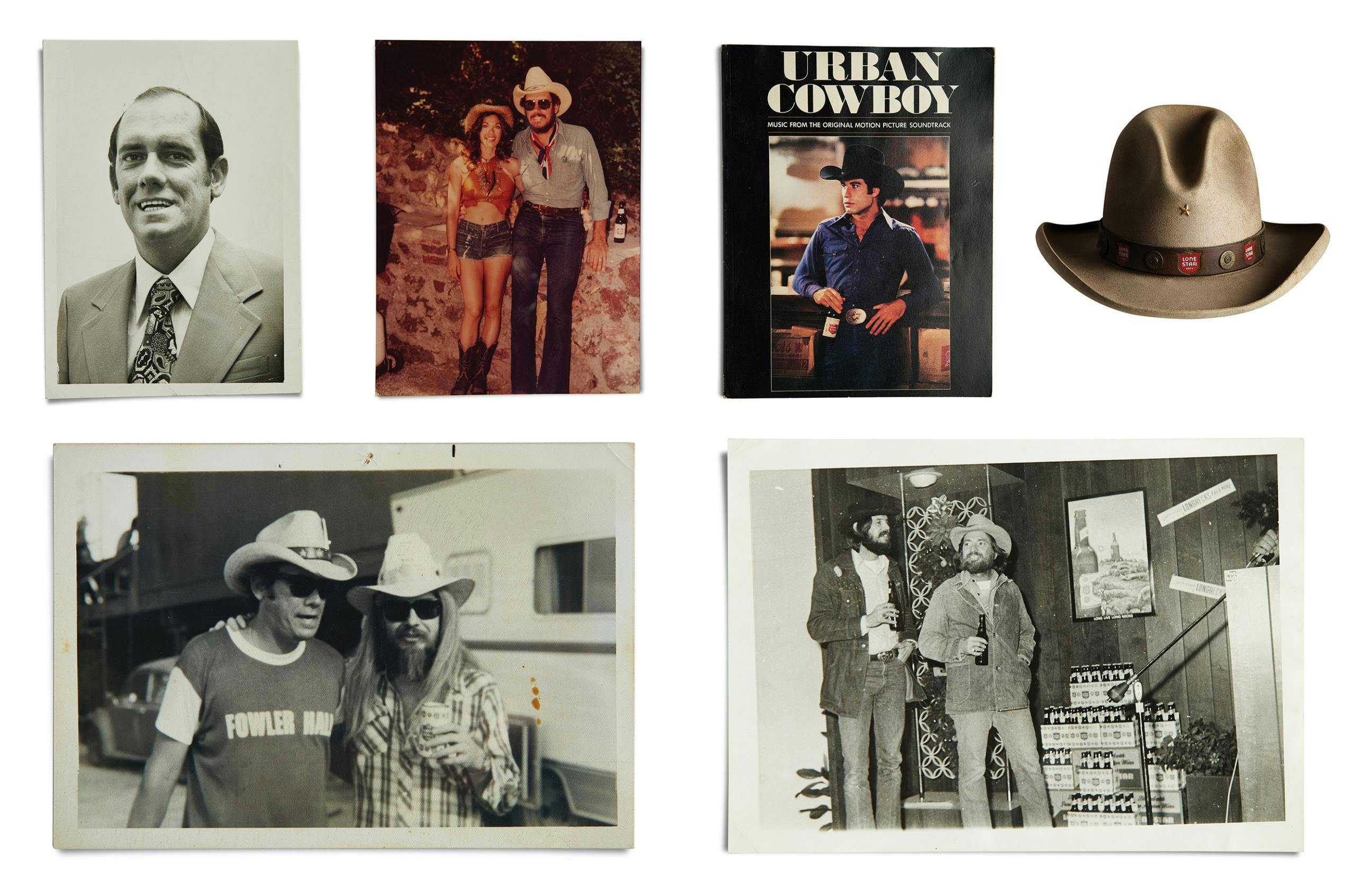

He insists, though, that the Austin success was a team effort, and he contends that Jersig’s truly essential move was the 1973 hire of Barry Sullivan. A onetime journeyman hockey player who’d appeared in exactly one NHL game in eight years on the ice, Sullivan had recently changed the fortunes of Narragansett, a small Rhode Island brewery, with a subversive strategy perfectly suited for Retzloff and his new friends in Austin. In the summer of 1969, Sullivan’s two sons had gone to Woodstock, and the stories they brought home intrigued him. His boys were hippies, so he knew the crowd was antiestablishment and disinclined to consume products they were told to. But he also knew there had been 400,000 of them at Woodstock. So Sullivan started to subtly connect their music to his beer. He sponsored concerts by acts like Led Zeppelin and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. Sometimes Narragansett wasn’t even sold at the shows. It was enough just to have its logo on the posters and its beer in the hands of performers.

When Retzloff took him to see Murphey in early 1974, Sullivan knew he could work that magic again. He and Retzloff enlisted the Armadillo consultants to create one-minute radio spots. After two initial efforts featuring a comedy team, they settled on a sole guiding principle going forward: spotlight the music. Their next ad opened with local Rolling Stone writer Chet Flippo describing the burgeoning scene—“Sometimes it’s called cross-country, sometimes progressive country, and it sounds like this”—before giving way to a pedal steel and the Lost Gonzo Band, the backing musicians for both Murphey and Jerry Jeff Walker. They played an abbreviated version of a new song that contained a single reference to Lone Star.

That summer, Lone Star commercials flooded the airwaves, but only in Austin. “We didn’t want it to drift into places like Schulenburg,” says Retzloff, “because we didn’t want those drinkers thinking we were a college beer. Old folks were so touchy back then.” But they did not limit their ad buys to country stations, and the exposure over rock radio brought the Gonzos new fans. And most important, Lone Star had radio audiences to themselves. Budweiser had chosen not to advertise while UT students were out of school.

There was another key moment. One night between Sullivan’s epiphany and Retzloff’s confab with Franklin, Willie Nelson approached Retzloff with a plan of his own. Just like Lone Star, Willie was chasing the youth market. Why not team up? Not with a formal endorsement deal or ad campaign, but something more organic. “It wouldn’t work,” recalls Retzloff, “if Willie looked like some bought-off whore.” So Retzloff made sure that Willie always had plenty of Lone Star, and so too the famous friends who played with him, performers like Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Leon Russell. As Willie grew from local hero to national icon, Retzloff either rode with him or, at a minimum, made sure his bus was loaded with Lone Star. Fans around the country started clamoring just to get their hands on Willie’s empties.

The tone for the next seven years was set by those Franklin posters, the best of which were paintings of landscapes dominated by giant longnecks. One bottle was enclosed in a Spindletop oil derrick and spraying literal liquid gold. Another had a covered wagon inside—think ship in a bottle—and was being dragged across the desert by a team of harnessed armadillos. For Retzloff, life became nearly that surreal; he went with Willie to the White House. Charlie Daniels showed up unannounced in a limo at the brewery one day; he was performing in Austin that night but wanted to see the place where longnecks were made. Another time Kinky Friedman called and asked Retzloff to smuggle some Lone Star to a taco party he was hosting in Hollywood. Retzloff took two cases on the next flight out and arrived at the stately Sunset Tower to find a hotel suite packed with one hundred of Kinky’s nearest and dearest. People like Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, Tom Waits, members of the Band, and one Rolling Stone. The cool guy, however, was the one who brought the longnecks.

That was in 1976, by which time Retzloff had sole control of the brewery’s music marketing. With sales at their peak, Jersig had cashed out his Lone Star stock and retired, and the new owners, Washington State’s Olympia, had parted ways with Sullivan. But Retzloff plowed on. Performers now begged to record a radio spot, acts with national hits, like Freddy Fender, Sammi Smith, David Allan Coe, and Asleep at the Wheel. Friedman recorded one with the Band backing him. Retzloff produced all of those, as well as four episodes of a music program that he syndicated to television stations around the state. When the Lone Star Cross-Country Rock Show proved too costly to continue, he shut it down and redirected part of his marketing budget to Austin PBS affiliate KLRU, making Lone Star the crucial first underwriter of Austin City Limits.

And then things got really weird. In the summer of 1980, the film Urban Cowboy did for cowboy boots and country music what Saturday Night Fever had done for wide white lapels and disco, kicking off a nationwide craze for Texas chic. The film’s signature image, the one used in movie posters and on the cover of its million-selling sound track, was star John Travolta leaning against a bar in a big black Stetson with a longneck in hand, the label facing out. It was one more by-product of Retzloff’s legwork. “Anytime a movie production came to Texas,” says Retzloff, “I’d find the prop master and offer some Texas hospitality, some free beer. And then I’d say, ‘I can help you make this look like a Texas scene.’ ”

Between Willie, ACL, and Urban Cowboy, Lone Star became a bona fide pop-culture phenomenon, not just hip with the college kids but sought out by the jet set as well. When the Kennedy family foundation threw a high-society, Texas-themed fundraiser in Manhattan—it was a chili cook-off at Bloomingdale’s—Retzloff booked the band and, of course, supplied the beer.

Lone Star’s golden age ended sometime in the mid-eighties. In 1983 Olympia sold out to G. Heileman, of Wisconsin, and the new owners brought a different strategy. They’d made Old Style beer the top seller in Chicago by pricing it on the cheap, and that was their plan for Lone Star. Retzloff pitched the idea of working with an up-and-coming country singer, George Strait, but Heileman balked. They shut down the endorsements and scaled back the advertising, investing instead in a price drop. Lone Star’s image descended with it.

His duties curtailed, Retzloff went back to work at the brewery, eventually running the gift shop and museum. In 1997, shortly after another new owner, Michigan’s Stroh, closed the San Antonio plant and moved production to Longview, Retzloff retired, ending his beer man’s career after 34 years. He received a little bit of glory in 2003, when Merriam-Webster included “longneck” in the eleventh edition of its Collegiate Dictionary. But by then he was making his living building boats.

Still, he remained a Lone Star man. He never quit drinking it, and he never let go of the heyday. In each of the three places where he now spends most of his time—his San Antonio home, his fishing place in Rockport-Fulton, and his nephew’s river house in Gruene—he created little shrines, filling them with Franklin posters, Willie photos, and novelty merchandise he helped design, like a belt buckle that doubled as a bottle opener and the Lone Star Dude cowboy hat sold by Austin hat maker Manny Gammage. In his closets and garage, Retzloff kept bankers boxes stuffed with bumper stickers, backstage passes, marketing memos, newspaper and magazine clippings, cassette tapes of radio ads, and videos of Willie shows.

Then this summer, Retzloff got a call from Austin writer Bill Wittliff, the namesake of an archive at Texas State University that focuses on literature and photography of Texas and the Southwest. The Wittliff Collections include manuscripts and personal papers by writers like Cormac McCarthy, Sam Shepard, and Bud Shrake, as well as items like the paddle John Graves used on the canoe trip that became Goodbye to a River and props and costumes from Wittliff’s own production of the Lonesome Dove miniseries. But the archive also has a music component, built around handwritten songs scrawled out by an eleven-year-old Willie Nelson.

Wittliff had been thinking for a few years about expanding those musical materials, and he asked Retzloff to donate his keepsakes. “We are interested in the human aspects of Texas, in the music, art, and customs, raunchy or not. Maybe preferably if they’re raunchy. His collection is a wonderful part of that. I had a lot of those things. I was hanging around Willie back then too, and if people weren’t handing you that stuff, you were grabbing it. Well, Jerry thought all that stuff up. And it’s the Texas that all Texans want to be part of.”

In late June, Retzloff sent more than a thousand items to San Marcos, or what an archivist termed “approximately twenty linear feet of artifacts.” I called him that afternoon, a few hours after they’d shipped. He answered but immediately handed the phone to Sally, who talked to me for about ten minutes before Jerry returned.

“Sorry about that,” he said. “I’d just gotten out of the shower and was dripping water all over the place, but everything’s okay now. You ready to talk?”

I told him I was and readied myself for more stories about the heady mystique of the national beer of Texas. Jerry was ready too, in his way.

“Hey, before we get started,” he said, “I got a quick question for you: You ever drink a Lone Star in the shower?”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Willie Nelson