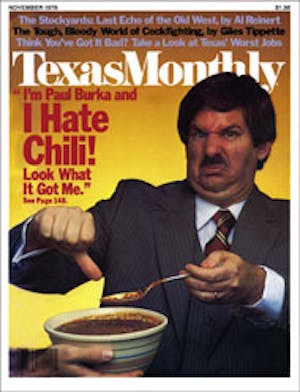

Don’t get the wrong idea. In the right place, which is my kitchen, and at the right time, which is about once a year, I rather enjoy the stuff. In recommended frequency, degree of culinary achievement, and level of enjoyment, it belongs in a category with beef liver: on the right side of the line dividing edibles from inedibles, but barely so. No, the loathsome thing about chili is not the concoction itself—how can mediocrity be dignified by loathing?—but chili lovers, a small but fanatical tribe whose uniting characteristic seems to be that they were born without a sense of taste. Not content with chili’s tiny footnote in the annals of gastronomy, they travel the country preaching their false gospel: that chili is an art form, that it has magical qualities, that it is our last link to the legends and ways of the Old West. To further their ends they promote the most insalubrious of Texas festivals, the chili cookoff; they glorify their unworthy subject in books and magazine articles and even publish a chili newspaper; they are attempting to revive chili parlors, a Texas institution that mercifully was on the verge of dying of natural causes; and, worst of all, they have inveigled that notorious body, the Texas Legislature, into declaring chili our official state dish.

The trouble with all this is that chili is third-rate swill. It violates every principle of good cookery. Imagine opening a Paul Bocuse or Julia Child cookbook and coming across a recipe calling for flavoring the grease and using the meat only for texture. Sacre bleu! It is true that the French sometimes elevate the sauce above the meat, but there any resemblance to chili ends. A French sauce is truly a merging of science and art, a Cartesian triumph resplendent with order and subtlety. It challenges the intellect, leading the epicure not only to savor the taste, but also to speculate how the delicate mixture was made. Handed a bowl of chili, our same gourmand would only wonder why. There is no pretense of subtlety. The cardinal purpose of this sauce is to assault the beef until it is subdued into a tasteless mush.

Another shortcoming of chili: it paralyzes the taste buds. Unlike other hot dishes—the peppery treats of southwestern China, the pungent curries of India—chili deadens rather than stimulates. Ten minutes after a bowl of chili, the mouth’s memory of the event is erased; but half an hour after, say, a serving of spicy bean curd with ground pork, the surface of the tongue still tingles with delight.

By this point unreconstructed chili heads, as they style themselves, undoubtedly will have concluded that I was born in the Bronx and put beans in my chili. Wrong. For a decade now I have upheld the honor of this state at an annual chili party co-hosted by, God help him, a pinto bean devotee from Missouri. In fact, it was in preparation for the most recent of these gatherings that I began to suspect the awful truth about chili. My rival vowed to prepare his recipe from scratch. He used only fresh herbs and spices: garlic, oregano, cilantro, cominos. He bought fresh chile peppers, dried them, ground them, and plunged the residue into his pot. He harvested tomatoes from his garden, ran them under the broiler to bring out the flavor, peeled them, and added the pulp and liquid to the bubbling mixture. I, on the other hand, used bottled spices, commercial chili powder, canned tomatoes, and a secret ingredient, about which more later. Yet my fast-food chili was the overwhelming choice of our guests.

When the euphoria of victory wore off, it occurred to me something was wrong here. Doesn’t Bocuse, acknowledged to be the world’s greatest chef, instruct would-be followers the world over to start with the best ingredients? If prefabricated chili can outshine the homemade variety, then either Bocuse or chili is on the wrong track.

I turned to Bocuse for additional enlightenment. “One must allow foods their proper flavors,” he writes. “It is a question of striving to retain the original taste of the food.” Yes, that sums up perfectly the difference between chili and the rest of the culinary world. While everyone else is trying to enhance natural tastes, chili obliterates them, offering not a taste but a sensation more closely related to the sense of touch—heat. I suspect that most diners would get as much sensual satisfaction from spending fifteen minutes in the August sun in downtown Dallas as they get from a bowl of chili.

To appreciate how little chili contributes to civilization, consider the recipe for the traditional Texas bowl of red. Start with coarsely ground lean beef, but never veal or U.S. prime—remember Rule No. 1 of chili cookery: the better the ingredients, the worse the chili. Using rendered beef suet; sear the beef until it whitens.

At this point the authorities diverge. Purists insist on using chile peppers, which violates a corollary to Rule No. 1: never use fresh what you can get out of a can—in this case, chili powder. I’ve heard it argued that chili powder leaves a cloying taste, but since cloying suggests too much of a good thing, the word would hardly seem to apply to chili. At any rate, if you’re committed to authenticity, stem and seed dried Jap-style peppers, then boil them in water for half an hour, or until the skin comes off easily. Grind the pods to a pulp and reserve the water. Then combine beef, suet, ground peppers, and water, bring to a boil and simmer for 30 minutes. Season to taste, adding oregano, salt, cayenne, and chopped garlic. The amounts don’t matter; you’re not making hollandaise. Bring the mixture again to a boil, cover, and simmer for 45 minutes, stirring occasionally.

At this point you will notice that you have prepared grease stew. Do not despair. Former Texas Governor Allan Shivers is credited with the recipe for salvaging this situation:

Put a pot of chili on the stove to simmer. Let it simmer. Meanwhile, broil a sirloin steak. Continue to simmer the chili and eat the steak. Ignore the chili.

If, however, you feel you’ve invested too much time to turn back now, you can skim the grease, even though the old-timers didn’t, or disguise it with a thickener like masa harina (Mexican corn flour), which would impart a tamalelike taste if it weren’t utterly lost among the peppers.

That is all there is to Texas’ heralded bowl of red. Now will somebody please justify how that glop could be passed off as . . .

The Official State Dish of Texas

Over the years the Texas Legislature has done just about everything man can dream up to do to his fellowman. In the not so recent past, for example, we have seen the Sharpstown scandal, a resolution honoring the Boston Strangler, simultaneous efforts to tax bread and exempt natural gas, and a reapportionment bill with districts in shapes and sizes unknown to geometry. But never has the Legislature so abandoned its sworn duty to enhance the public welfare as when it certified chili as the official state dish.

This nefarious scheme was hatched in the mind of an otherwise honorable legislator from Marshall by the name of Ben Grant. If the name sounds familiar, he was the author of a death-by-injection bill to provide more humane capital punishment—a matter someone responsible for making chili the state dish has good reason to be concerned about. Grant’s initial purpose was to immortalize the farkleberry as the state berry, but when this proved too much even for the Legislature, he started his chili crusade.

Now this kind of nonsense goes on all the time in legislative bodies. Usually it is quite harmless. New Mexico lawmakers, for example, have named both the chile pepper and the pinto bean their state vegetables. Jack Garner of Uvalde once tried to have the prickly pear cactus declared the state flower instead of the bluebonnet. He failed, but he was known thereafter as Cactus Jack and went on to become vice president under Roosevelt. Perhaps Grant harbors similar ambitions and hopes to become known someday as Greasy Ben.

The record shows that the resolution passed the House with a minimum of controversy. There were a few attempts to amend the proposal—some South Texans tried to substitute menudo, a member from Port Arthur offered gumbo, and Craig Washington, from Houston’s Fifth Ward, made a pitch for chitterlings. But ultimately it passed, 70 to 36. Since the Senate forfeited any pretense of acting in the public interest years ago, chili was over the last hurdle.

All this could be considered rather innocuous and in good fun were it not for the fact that there is a food with a valid claim to the title of official state dish, and it is not chili. I am speaking, of course, of barbecue.

The case for barbecue is overwhelming. It is the food most identified with Texas in the public mind. When West German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard came to the LBJ Ranch, what did Lyndon serve? Not chili. (And if he had, Erhard wouldn’t have gotten the traditional bowl of red. Johnson’s recipe called for tomatoes and onions.)

Furthermore, barbecue is aesthetically pleasing. What should Texas place alongside Virginia’s magnificent Smithfield ham? A raven-black brisket, sliced to expose gently flowing juices? Or a bowl of what appears to be a failed beef stew? Barbecue is capable of endless variety, depending on wood, sauce, and type and cut of meat. But despite the many recipes for the original bowl-of-red type of chili, ultimately they all taste alike, varying only in torridness. Barbecue cookery is truly an art, requiring such skills as fire building, wood choosing, pit knowledge, sauce manufacture, and carving. The hardest thing about preparing a pot of chili is finding someone to eat it. Finally, the process of natural selection has proved barbecue’s superiority over chili. Most restaurants of less than the highest pretensions offer something they call chili, but it is next to impossible to get a true bowl of red in a restaurant these days. Chili parlors, once the scourge of the land, have all but disappeared. In the Dallas Yellow Pages, for example, there are 109 listings under barbecue, but only 2 under chili. The public has spoken. Why wasn’t the Legislature listening?

I raised this point to Greasy Ben recently, and he admitted to some twinges of conscience over barbecue. But he claimed to have done research demonstrating that barbecue did not originate in Texas, while chili did. So what? Stephen F. Austin didn’t originate here either, but we named our capital after him.

I suppose I should pause here to make what politicians call a full disclosure, before some vengeful chili head accuses me of concealing a conflict of interest. I am a member, indeed a founding member, of the Texas Barbecue Appreciation Society. Our organization was established in 1973, and its first official action was to propose a legislative program that included changing the state seal to a brisket surrounded by a sausage link and exempting barbecue entrepreneurs from air pollution regulations. Unfortunately, the six founders split soon after the society’s inception into sauce-on-the-side traditionalists and sauce-on-the- meat revisionists, and we have thereafter been unable to add any members or transact any business. That was all the opening the powerful chili lobby needed.

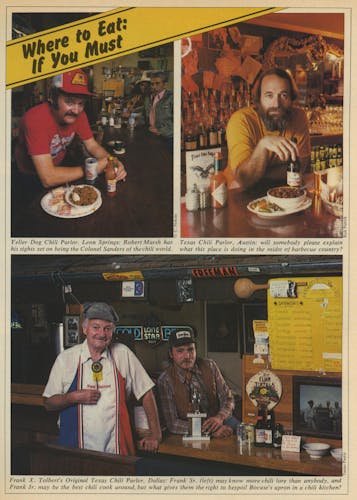

Scoff not. There really is a chili lobby. Check the records of the 1977 legislative session and you will find a Robert Marsh of San Antonio registered in favor of House Simple Resolution 18. With financial contributions from Chili’s Restaurants and the manufacturers of Wolf Brand canned chili, Marsh brewed what he claimed to be the world’s largest pot of chili to feed to the members of the Legislature: 259 gallons weighing over 2500 pounds. Marsh also persuaded Pearl to donate 24 cases of beer, which several lawmakers told me had more to do with the bill’s ultimate success than the taste of the chili. I am happy to report, however, that there remain some standards in the world. Marsh submitted evidence of his largest pot of chili to the editors of the Guinness Book of World Records, but they wrote back that they did not consider it a significant achievement.

As for Grant, let it be noted that justice works in strange ways. The man who started the chili boom now suffers by his own hand. As a minor celebrity in the chili world, Grant is called upon to eat more bad chili than anyone in Texas. He is highly sought after as a judge for . . .

Chili Cookoffs

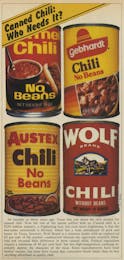

The main thing you have to understand about chili cookoffs is that most of the people who organize them care no more about chili than the exchange rate of the lira. This has been true from the very first cookoff, held in the Big Bend ghost town of Terlingua eleven years ago. While chili heads would have the rest of the world believe that the contest was designed as a test of Texas-style chili against chili as it is known in the rest of the world (stocked with tomatoes, onions, and beans), in fact it began as just another public relations gimmick. A year earlier Dallas Morning News columnist and Texana authority Frank X. Tolbert had written a book called A Bowl of Red, incorporating everything one could want to know about chili, which apparently wasn’t much. In that golden age of chili antiquity, the public hungered neither for the dish nor for knowledge of its past. Then somebody hit upon the idea that a chili competition between Wick Fowler, Texas’ acknowledged chili master, and California restaurateur Dave Chasen, who kept Hollywood plied with vegetabled chili, might stir up enough free publicity to boost sales of Tolbert’s book.

At that point providence took a hand. Chasen was sidelined by illness and New York author H. Allen Smith was persuaded—some would say tricked—to take his place. Smith’s credentials, in the eyes of the Texans, were limited to two: he had written an article for Holiday magazine that summer proclaiming Nobody Knows More About Chili Than I Do, and he’d published his chili recipe, thereby revealing himself as an easy mark. Smith did not win the cookoff, which ended, appropriately, in a dead heat, but he did go on to write a book and numerous magazine articles about the match. Fowler went on to build his Caliente Chili Company, which markets his spice mixture, into a $1 million company before his death in 1972. But the real winner was Tolbert: his book is still being printed in hardcover editions and he’s opened his own chili parlors in Dallas.

Terlingua proved so successful that chili cookoffs began to proliferate. The attraction was not just the chili but a unique camaraderie shared by 2000 or so chili heads—most of them male, middle aged, and middle class. At a time when the United States was going through Viet Nam, black power, and student protests, the cookoffs were one of the few rituals left in which America’s past could be celebrated without fear of drawing picketers and demonstrators. The San Marcos Chilympiad, the Texas state championship, started in 1970; when it barred female entrants, a Hell Hath No Fury cookoff sprang up in Luckenbach. Today chili cookoffs take place from Hong Kong to Scotland, but Texas is still the epicenter. Someone who started on July 4 of this year could have followed the chili circuit to Comfort, Alice, Floresville, Llano, Victoria, Schulenburg, Houston, Pleasanton, Thorndale, Austin, San Marcos, Junction, Houston again, Plano, Beeville, and Flatonia, before heading for Terlingua on November 4 for this year’s world championship. I have attended more of these than I like to count—two—and as a result, I’ve developed a short list of survival rules for chili cookoffs.

(1) If you value your health, don’t eat chili. This advice is somewhat superfluous since hardly anyone goes to chili cookoffs to eat chili. It is hard to imagine anything less appetizing, for example, than the San Marcos Chilympiad. The event was held this year in mid-September on a malarial weekend after several days of heavy rain. Officially the temperature was in the low nineties, but the combination of the sun’s rays reflecting off the white gravel, which reclaimed the cookoff site from swampy fields on all sides, and the heat unleashed by 245 Coleman stoves and wood fires drove the heat factor close to a hundred. Everyone seemed much more interested in the beer concession than in chili, leading me to suspect that the only people really enthusiastic about chili cookoffs these days are beer wholesalers. (The Corsicana cookoff last spring is believed to be the first ever held in a dry town.) Spectators shuffled from booth to booth, trying in vain to distinguish one porridge from the next. Finally I saw a reporter from an Austin TV station, obviously acting out of a sense of duty, ask for a taste at a booth labeled Dippers Chili.

“You got somethin’ funny in this chili,” he said to a ten-year-old girl who was staffing the booth. “Tell the truth. What’s in it?”

“Dog shit!” the child fired back.

Aside from recalling Barry Goldwater’s accusation that Texans don’t know their chili from leavings in a corral, the exchange says a great deal about what has happened to chili and chili cookoffs over the years. Their rationale has evolved from little more than an elaborate prank shared by friends into a deadly serious commercial venture for local organizations. (With an estimated 50,000 spectators who attended the Chilympiad paying $1 apiece, not to mention entry fees, the cookoff grossed a tidy sum for a San Marcos civic organization.) The camaraderie and good feelings that once distinguished them are missing. Cookoffs have gone the way of rock music festivals: from love feasts to obscenity and violence. The Thorndale cookoff ended this year in a free-for-all with several spectators suffering stab wounds, and the Terlingua event had to be relocated to a nearby desert inn to aid security after motorcycle gangs invaded the 1975 championship. The older chili heads don’t travel the circuit anymore—“Some of these people have gotten really nuts,” says Tolbert, who didn’t make it to San Marcos—and in their place are thousands of urban cowboy types driving RVs and wearing T-shirts with legends like Linda Lovelace Gagged on My Chili.

With the old chili heads relegating themselves to the sidelines, chili cookoffs have taken an ironic twist. Originally conceived to praise the sainted bowl of red, they have all but obliterated it. Realizing how little variety there is in straight chili, contestants have tried desperate measures to catch the attention of judges. In San Marcos I saw Hawaiian chili with pineapples and pork, and gumbo chili with okra and spinach. Tolbert, a braver man than I, has tried mushroom chili at Lake Tahoe, sour-cream chili in New Jersey, butterbean chili in Ohio, alligator chili in Louisiana, and has seen first prize at Terlingua captured by a chili with limes and sweet bell peppers. This lunatic fringe seems to grow each year. Even those who claim to be traditionalists are suspect. Walking around during the hours when the chili was being prepared, I saw the following heresies: sweet bell peppers, Rotel tomatoes, rosemary, chicken broth, cheese, and a can of Gebhardt’s Chili-Quik.

(2) Never under any circumstances listen to anything that’s said over the public address system. At the Chilympiad spectators were continually under siege from an announcer whose job was to whip up what he perceived as the crowd’s lagging enthusiasm. “Come on now, folks, it’s time for the egg toss, entries closing in ten minutes.” Chili cookoffs are not very exciting—watching someone cube and brown beef is not likely to replace pro football as the nation’s leading spectator sport—but when the weather is mild and the surroundings are special and the mix of people is just right and enough of them know each other, a cookoff can be a considerable improvement over a tavern. It is the announcer’s aim to insure that this situation does not develop; he substitutes for the nagging waitress who’s always trying to sell you another beer. “All right, on the count of three, let’s all yell, ‘Yea, Rattlers!”’ There is no peace. One of the mike men fancied himself a regional Howard Cosell; he narrated the egg toss using Cosell’s strange syntax and stilted rhythms. The purpose of the contest is to see which pair can throw a raw egg the greatest distance and catch it without breaking the shell; one failure was described thus: “It decides to completely disseminate itself at the point at which it was intended.”

(3) Ignore the judging. There are two kinds of chili judges: fixed and biased. Organizers of chili competitions have run into the same kind of problem the government faces when it tries to regulate a controversial industry like natural gas: you don’t want someone who doesn’t know anything about the subject, but anyone who does is certain to have prejudices set in concrete.

“Tell me who the judges are and I’ll tell you who’s going to win the cookoff,” says one chili head who claims to have won 38 competitions and apparently knows a lot of judges. The bowls that go to the judges are not supposed to be identifiable, but often there is a distinguishing characteristic, such as the limes that carried a Californian to an early Terlingua championship. In fact, Terlingua has a terrible reputation for shenanigans. Judging panels in the early days were stacked, and, though Tolbert in a revised edition of his book headlines a chapter “Honest Judging at Last,” rumors of judicial favoritism persist.

So you can’t count on getting a bowl of championship chili at a cookoff, even when it’s certified as such. As chief of counterinsurgency for the Barbecue Appreciation Society, I’m convinced that the shady judging tactics that go on at chili cookoffs are a deliberate attempt to protect the chili mystique. After all, if it were possible to identify a particular batch of chili as indubitably the best, the truth about chili would be exposed like the emperor’s new clothes. This way it is always possible to maintain that a better bowl exists. Don’t play into their hands. If you want to make an honest judgment about chili in a controlled situation, try one of Texas’ new . . .

Chili Parlors

The origins of chili are as mysterious as the esteem in which it is held. There are almost as many theories as there are recipes, but the most likely is that it developed from a North American Indian staple known as pemmican: dried beef pounded fine and mixed with rendered suet. All the authorities agree that chili cannot be blamed on Mexico, for it is unknown in Mexican cookery. In A Bowl of Red, Tolbert even cites a modern Mexican dictionary that describes chili con carne as “a detestable dish sold from Texas to New York City and erroneously described as Mexican.”

Whatever its origins, chili was refined in San Antonio during the nineteenth century into the dish as we know it today. Just as the fiery Chinese dishes of Hunan descended from kitchens of peasants who could afford pepper but little meat, so chili got its start among the very poorest San Antonians in the years before Texas independence. The first chili parlors did not appear until the 1880s, however, and even then they were just open-air U-shaped tables set up in Military Plaza by women who quickly became known as “chili queens.” This tradition survived for more than half a century, until Mayor Maury Maverick in 1943 chased the chili queens off the plazas for health reasons.

It did not take long for chili to penetrate the land. Texans traveling to San Antonio brought back word of the confection to their hometowns, but the Typhoid Mary of this plague was the proprietor of the “San Antonio Chilley Stand” at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Thereafter chili spread to the Midwest, though usually in an adulterated form. Cincinnatians, for example, still put lettuce and spaghetti noodles in their chili. In Illinois, more than the form is adulterated: Springfield claims to be the “Chilli [sic] Capital of the World,” perhaps to insure that it will have no rival.

For a time chili parlors were so prevalent in Texas that Will Rogers is said to have judged towns by the quality of the chili. The parlors seemed to go along with other Texas traditions: a chili parlor sat across the street from Neiman-Marcus in downtown Dallas and another was located near the headquarters of the King Ranch in Kingsville. But those emporiums are years gone. I asked a number of chili heads if they knew of any old-time chili parlor that survives. Not even Tolbert could name one.

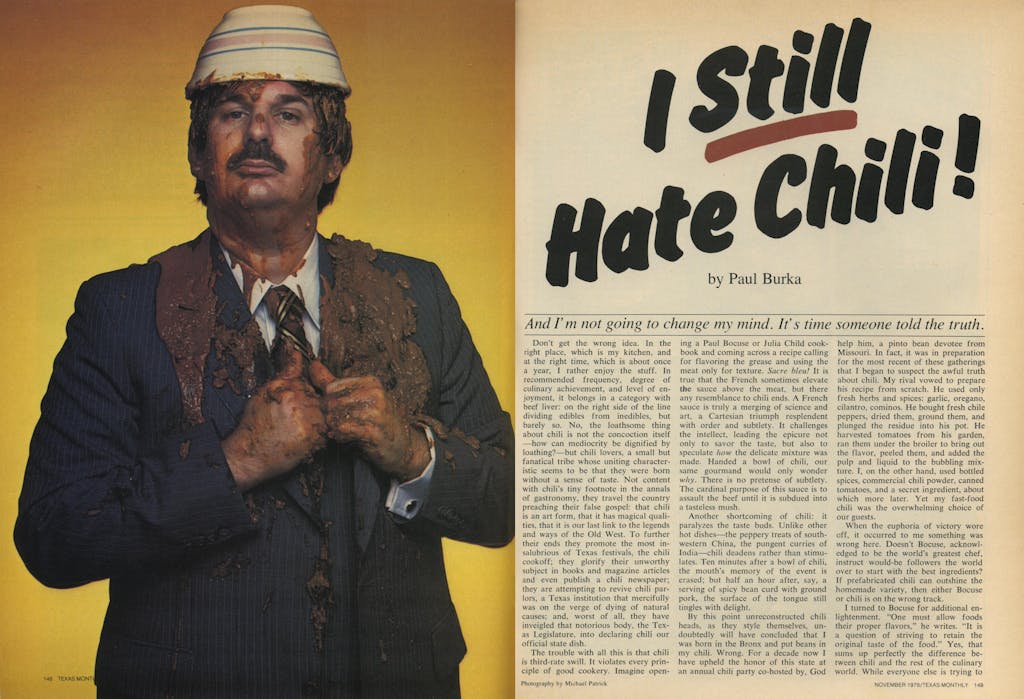

However, Tolbert stubbornly insists on doing his part to keep the tradition alive. His Frank X. Tolbert’s Original Texas Chili Parlors in Dallas (3802 Cedar Springs at Oak Lawn and downtown at 802 Main) offer the best bowl of red that can be bought in Texas today—for whatever that’s worth. The meat is tender, but still chunky enough to offer some resistance. The peppers don’t overwhelm the other seasonings, though they come closer than they should; you can restore the balance by adding Tolbert’s homemade hot sauce to the potion, for the salsa imparts the slightest hint of sweetness that more than makes up for the increased heat. The consistency is just right: no thickener, but an ample proportion of meat to chili that makes one unnecessary. Finally, the color—a deep purplish red, not a soggy reddish brown or a telltale tomatoey cardinal—bespeaks authenticity. The only trouble is the medium itself. Like a painting where the artist used lubricating grease and ox blood, one asks of Tolbert’s chili: it’s interesting, but is it art?

The downtown location is more reliable, for the Tolberts (Frank Jr. is the head chef) don’t often get out to Cedar Springs to make the necessary mid-course corrections in the family formula. I had bowls on consecutive days at Cedar Springs and found them wildly different in both flavor and consistency. Unfortunately, the downtown parlor is open only on weekdays and only for lunch.

The Cedar Springs parlor is designed with the cocktail trade in mind: clean, dark wood tones; split levels; immaculately framed posters advertising previous Terlingua cookoffs; and intimate lighting. When my bowl of red arrived, the dim light glistened on the grease like gas flares dancing on the Houston Ship Channel. At the time I wished I could have inspected it more closely, but my next venture was to Chili’s (7567 Greenville and 4291 Beltline in Dallas and 5930 Richmond in Houston), where the greenhouse-style decor allowed me to see all too well. The chili was so thick I thought it had been topped off with epoxy, and as I churned it with my fork, I occasionally exposed white things that didn’t look like they belonged there. It proved to taste uncomfortably close to canned chili, though there was extra beef and such an excess of cumin that I briefly thought about investing in cominos on the commodities market. The tipoff on Chili’s is that, despite its name, its T-shirts feature a large picture of a hamburger.

The Texas Chili Parlor in Austin (1409 Lavaca, no relation to Tolbert’s) falls somewhere in between the Dallas extremes. The chili—actually the chilis, for there are three degrees of hotness, each from a different pot—is passable but unremarkable, and the spices seem to be competing among themselves for supremacy.

The fourth and last parlor that has been spawned by the chili revival is in Leon Springs, a tiny community twelve miles from San Antonio’s northwest fringe just off Interstate 10. This peaceful Hill Country setting seems an unlikely place to start a national business, but if the Yeller Dog’s Chili Parlor thrives, the wooden saloon that is its home may one day be as famous as the golden arch in Des Plaines, Illinois, that marks the spot of the original McDonald’s. At least that’s the hope of proprietor Robert Marsh, the one-time chili lobbyist who now hopes to do for chili what Ray Kroc did to hamburgers.

“You can bet there’s going to be a national chain of chili parlors soon, and I hope it’s gonna be mine,” Marsh said as he spooned some chili into a bowl. “If this place flies, we should take off in a year or so. We’re already marketing our chili mix.” Marsh produced a red and yellow package labeled Yeller Dog’s Hoot ’n’ Holler Certified Texas Chili Fixin’s. I noted the phrase at the top: “Chili! The official state dish of Texas!” Along with the spice package comes a recipe for “Prize-winning gourmet-type chili,” calling for pinto beans and sour cream. (“You can put cooked beans in your bowl of chili if you want,” I recalled Tolbert saying, “but never cook them together. The chemistry’s all wrong.”)

Marsh laughs about the chili-lobbying incident—it never occurred to him that he was technically a lobbyist until a newspaper reporter, no doubt a barbecue lover, called to ask whether he’d registered—but he’s serious about chili. He even has what he and one San Antonio radio station call a chilicast with sports scores and news of chili cookoffs. His own chili involves no shenanigans. When I asked him about tomatoes, he winced: “That’s Yankee influence. They wanted it to taste like spaghetti sauce.” Marsh uses no tomatoes, no onions, no thickener. Not very hot, his chili leaves a pleasant aftertaste, but to compare his chili to Tolberts’ is like comparing Tolbert’s to . . .

The Best Chili in the World

Mine, naturally. But before I reveal the secret of its creation, I must dispense with one last myth:

There can be no such thing as a recipe for chili.

My advice is to give up trying to codify the outcome of a pot of chili. It can’t be done, and what’s more, it shouldn’t be. Chili should be approached the same way I once heard a sculptor describe his profession: you take a block of marble and chip away everything that doesn’t look like David. In preparing chili, take the necessary ingredients—amounts are immaterial—and chip away at the beef until you get something that tastes like chili.

The recommended ingredients are: browned beef, beef fat, garlic, chili powder, cumin, cayenne, paprika, salt, white pepper, oregano, basil, and—taste taking precedence over tradition—canned tomatoes and onions. The idea is to keep adding elements in whatever quantities are necessary until the flavors are neutralized. The only rule I can offer is that too much cumin or cayenne will ruin the pot just as surely as too little garlic or onions. When your taste buds are no longer able to detect the dominance of any one spice, the proper point has been reached. You are now ready to transform your creation into chili with the addition of the secret ingredient.

The peppers that are supposed to be used with chili are incapable of working in harmony with natural flavors. What is needed is something that will set off the spices so that they fuse together in a burst of heat and light and flavor, as though a nuclear explosion had suddenly occurred in the pot. After years of experimenting, I have discovered that the Chinese red pepper is the uranium of the picante world. A bottle of Szechuan paste with garlic, available in any Oriental market, will enhance every taste in the mixture even as it adds a fiery hotness.

Just writing about it makes me hungry. In fact, I think I’ll go have a bowl—of sauce. Along with my barbecue.