Of all the tamales made by San Antonian hands in May 1961, one was destined for a place in history.

The tamale, according to an account from the time, was made of “pork, pimentos, garlic and other spices” surrounded by masa and, for logistical reasons, was wrapped in cellophane rather than corn husks. The Associated Press reported it weighed seventeen pounds.

News of the behemoth ran in papers in cities from Miami to Indianapolis to Bridgewater, New Jersey. Reports described a fiesta honoring “the biggest tamale in the world,” after which the miracle of maize was placed in an armored car and taken by motorcade, with “colorful Mexican charros riding honor guard,” to the San Antonio airport. Its airwaybill on Eastern Air Lines carried instructions to “deliver immediately on arrival.”

It was headed to the White House, a birthday gift for President John F. Kennedy “on behalf of Citizens of the United States of Latin Heritage.”

Papers quipped that the Boston-bred president was more of a fish–and–baked beans sort of guy. “JFK May Need Bromo on 44th Birthday,” read one headline. Roberto L. Gomez, Esq., president of the San Antonio Social Civic Organization, which had sent the tamale, told a reporter he wasn’t sure what sort of reception the tamale would receive.

It had been seven months since Mexican American organizers in “Viva Kennedy” clubs turned out the votes to carry Texas for Kennedy in the election of 1960. The corn colossus would be an unmistakable reminder of that fellowship, and of the president’s indebtedness. Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, who resurfaced the story of Gomez and his jumbo food campaign in 2018, wrote that the gift was “done tongue-in-cheek, but also as a reminder to presidents: We Mexicans have political power, too.”

The political heft of the gift was clear. But then came a mystery: the tamale disappeared. Three days after its grand send-off from San Antonio, the Tampa Tribune declared the “Giant Tamale for Kennedy Has Gone Astray.” On May 26—less than a month removed from the Bay of Pigs invasion, and one day after Kennedy announced plans to put a man on the moon—White House reporters pressed the administration for answers about the tamale’s whereabouts.

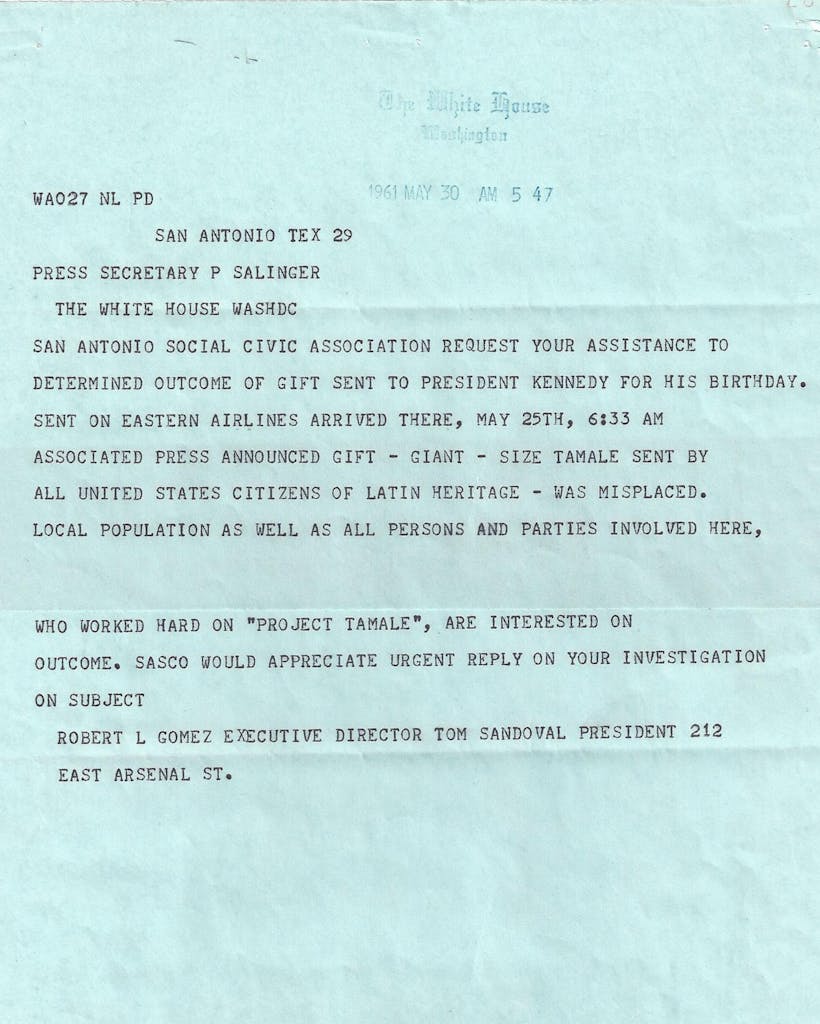

Gomez sent a telegram to White House press secretary Pierre Salinger: “Local population as well as all persons and parties involved here, who worked hard on ‘project tamale,’ are interested in outcome,” it read.

“Tamale for Kennedy Is Missing,” announced a Kansas City Times headline. “A king-sized tamale which was supposed to warm President Kennedy’s palate couldn’t be located today,” the AP reported, adding, “That takes quite a bit of doing, since the presence of a tamale can be detected at a considerable distance.”

Like Amelia Earhart and D. B. Cooper, the comestible marvel seemed to be gone without a trace; in its place were speculation and a growing legend. Only Gomez, Geppetto to the jumbo tamale, claimed to know its fate.

Gomez had come to Texas in 1953 from Ottawa, Kansas. His hometown paper later suggested readers might remember him as the “Bobby” who’d worked at a large hotel in the center of town. Gomez said he had also been employed by the Kansas governor as an emissary to officials in Mexico.

Sam Alvarado, a 92-year-old San Antonio civil rights leader and attorney, says he first knew Gomez as a tamale vendor on the city’s West Side. He also recalls Gomez getting hassled at one point by city inspectors who said his mobile operation was unsanitary—a common excuse, Alvarado recalls, to run Mexican Americans out of business. By 1961, Gomez was supervising the cafeteria at USAA headquarters, the largest cafeteria in South Texas, Gomez said. He went on to be a manager at Mario’s on South Pecos Street, then at outposts of a local chain called Take-A-Taco and at the Taco Territory restaurant downtown.

But his true passion seemed to lie in the city’s social scene. In San Antonio, Bobby from Kansas became Roberto L. Gomez, Esq.—the title being an abbreviation of his mother’s family name, Esquivel. In the society pages of the San Antonio Express-News, he appeared as an official of the San Antonio Social Civic Organization, or SASCO, hosting society balls, fundraisers, and holiday parties.

After penning a column in which he reported his own resignation from the group, Gomez continued as a columnist for the Express-News. He also became a sort of recurring character in Paul Thompson’s columns on the paper’s front page, sometimes sharing a bit of political humor from the city’s West Side.

In April 1961, Gomez ran in a four-way race for San Antonio City Council, a seat which was at the time elected at large. It was a system designed to guarantee Anglo control of the largely Hispanic city and lasted until the advent of single-member districts in 1977. Gomez lost his bid for City Hall but pivoted quickly to his plan to send a big tamale to the White House.

Alvarado recalls the Kennedy tamale was inspired by a conversation with Congressman Henry B. González. As a teenage altar boy at the San Fernando Cathedral, Alvarado says he witnessed a conversation between Gomez and the congressman. “[González] actually told Mr. Gomez to do that,” Alvarado says. “He’s the one who said to do that because we need the political power that they have.”

The answer to who, if anyone, ate that tamale may be lost to history, but on June 9, 1961, Kennedy replied directly to Gomez and SASCO President Tom Sandoval. Skirting the question of its consumption, Kennedy thanked the group for “remembering my anniversary in such an interesting manner.”

The next year, when Kennedy got a birthday song from Marilyn Monroe, he also got a red, white, and blue donkey piñata filled with candy from Gomez and SASCO. This time, González personally intervened to ensure the gift’s safe arrival. González did so again in 1963, when the group sent a Texas-shaped birthday cake with a replica Alamo, plus “the world’s largest piece of Mexican praline candy.”

The birthday cake would be Kennedy’s last, but Gomez was just getting started. He continued to honor politicians with large-format Tex-Mex foods well into the next decade on behalf of the National Taco Council, which he formed in 1965. “Its goals,” the Los Angeles Times later wrote, “include creating in Mexican-Americans a greater pride in their own cuisine and enhancing the reputation of Mexican food and culture everywhere.” Gomez and his Taco Council led the promotion of the first National Taco Week, coinciding with González’s birthday on May 3.

In 1968, the year of the World’s Fair in San Antonio, the council’s Taco Week proclamation decreed: “No finer monument could be given by the nation as the acknowledgement of a food such as the taco, so much loved and recognized in this region of the country, than to know that it does stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Hamburger or Hot Dog.”

“No matter how seemingly superficial or frivolous, it was history,” Arellano says. “It was early advocacy work, telling the president of the United States, ‘We have rights; our culture exists; our people exist. We deserve the same rights as everyone else.’ ”

Gabriel Quintero Velasquez, a West Side activist, artist, and youth mentor, says he doesn’t remember Gomez’s restaurants or the Taco Council among the centers of San Antonio political movers, but he says Gomez’s gleeful promotion of taco culture would have been a revolutionary act.

“I remember when we were kids in elementary school, in the second half of the sixties, we would get our bread and stuff the meat in them like tacos, and the teachers would come and tell us we couldn’t eat that way,” Velasquez says. “To watch the change has been beautiful. . . . Being proud of your food is such a loving act.”

John Bustamante, whose father, Albert Bustamante, was once honored with one of Gomez’s giant tacos, says his dad employed his own brand of “taco diplomacy” when he was elected to Congress in 1985. “Mexican food was still a novelty at that time in Washington, D.C.,” he says. His father had trays of Mexican food driven from San Antonio and threw fiestas for his Capitol colleagues. “The food was a way to break into circles that would not have been available otherwise,” he says.

Like the Taco Council stunts, these events were meant to impress Anglo politicians with Mexican American culture while asking them to step only slightly beyond their comfort zone. There were margarita machines and photo ops in serapes and sombreros. “You look at it, and it’s a little too archetypal, a little too stereotypical for what we think of as proper representation now,” Bustamante says, “but it was an introduction. What it really was was effective.”

Arellano says it’s important to remember the context before judging too harshly. “That’s just a history of ethnics in the United States. The pioneers have to do things that the people who follow them are probably going to cringe at,” he says. “But we were not there. We were not the ones trying to make breakthroughs at a time when it was far harder than today.”

Inspired by Gomez, last year Arellano became a founding member of the International Taco Council along with a group of journalists, poets, cooks, and scholars “to spread the joy of the taco in earnest and in jest,” according to the organization’s manifesto. The effort to resurrect the organization was spearheaded by Texas Monthly taco editor José R. Ralat and a small group of writers from Detroit to California.

That spirit of playful appreciation, the bombast mixed with heartfelt pride, is evident in the original Taco Council’s exploits. Gomez promoted Taco Week “with literature which says that eating tortillas makes hair grow,” as well as with the story of a San Antonio professor who lost six pounds in a week of eating only tacos. Years after the Kennedy tamale went missing, the Taco Council said it had in fact been “lost at the White House Kitchens.” Originally listed at 17 pounds, the tamale was later described as a “gustatory whopper monster” weighing 48 pounds.

At some point in the 1960s—the year is uncertain—Gomez and the Taco Council delivered their next overture to Washington: a 55-pound taco for President Lyndon Johnson. Paul Thompson remembered it as “the World’s Largest Taco” in an Express-News column in 1973, and Gomez later referenced the taco in reports from the AP and United Press International.

But Gomez never seemed to get his story straight when it came to Richard Nixon. In January 1972, Gomez announced plans to send Johnson’s successor an even bigger taco, “a delightful 95-pound Mexican morsel.” But by January 1980, Gomez said he’d sent Nixon a “Big Enchilada” instead, a joking reference to an infamous line in the Watergate tapes. And just months after that, Gomez told the AP that, in fact, the Taco Council hadn’t sent Nixon a thing. “We telephoned the White House and they said ‘Go ahead and keep it. The president doesn’t want it,’ so we said to hell with you,” Gomez said.

The record is clearer on his gift to Gerald Ford in July 1976, a few months after the president visited the Alamo and tried to eat a tamale with its husk still on. The council, of course, sent Ford an oversized tamale. But unlike the one for Kennedy, this one came wrapped in 165 corn husks. Sources variously listed its weight as seventy, eighty, or one hundred pounds. Prepared by Goas’ Tamale Factory and displayed in a six-hour ceremony before being shipped via air freight, the tamale was never acknowledged by the White House. But both Ford himself and the giant tamale were acknowledged with Bum Steer Awards from this magazine.

In October 1976, Jimmy Carter made a campaign stop at the Alamo, and the Taco Council prepared a 110-pound chalupa for him, filled with 10 pounds of beans, ten heads of lettuce, and 5 pounds of Georgia peanuts. Henry B. González had intended to present the chalupa to Carter personally, but it got “lost in the shuffle,” Albert Bustamante told the Express-News. Before Carter could receive it, the paper reported, “people at the Alamo tore huge chunks from the giant chalupa.”

In 1980, when the Taco Council made a 150-pound taco and auctioned it for charity, a reporter asked what Gomez might send Ronald Reagan, but Gomez shook his head. “I don’t know,” he said. “We’ve done about everything.” There had been talk of sending a 150-pound burrito, he said, but only talk. Three years later, Gomez died at age 49.

Texas Monthly inquired at presidential archives seeking clues to what happened to the Taco Council gifts sent to Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford, but, with the exception of the 1963 Kennedy cake, only staff at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library found mention of these large foods. Among the library’s records is a shipping bill for the 1961 tamale, including its intended recipient, “President J. Kennedy,” and its weight, recorded at 15 pounds.

That evidence of the tamale’s actual weight does not seem to have been reported anywhere else before now. In fact, long after its disappearance, the Kennedy tamale only seemed to grow in the popular retelling. First, the press listed it at 17 pounds in 1961, and later at 48 pounds, it was eventually recalled to have weighed “about 175 pounds” in a 1972 Express-News column by Paul Thompson. Gomez, Thompson wrote, “always has insisted the late president no doubt ate ‘at least half of it.’ ”

To Arellano, Gomez and his feats of food represent a folk history with a truth that’s deeper than the facts. “If he was fibbing over the years, it’s because he was proud of what he did,” Arellano says. “Look, a seventeen-pound tamale is still a big-ass tamale.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Tacos

- Tex-Mex

- Tamales

- JFK

- San Antonio