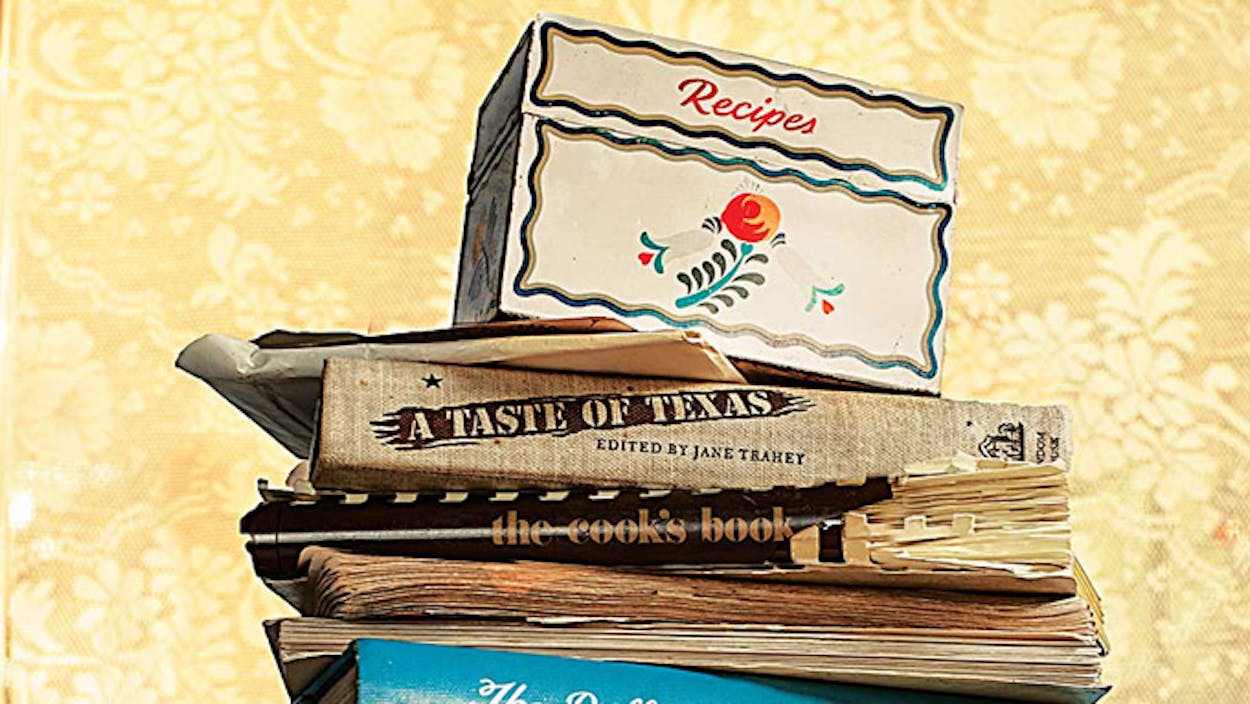

From time to time, I launch a campaign to deaccession or “depileate” some of the clutter that accumulates when one has lived more than thirty years in the same house. The library is too daunting to tackle, but the pie safe, stuffed with cookbooks, old Gourmet magazines, and a flutter of yellowed recipes torn from newspapers, seems doable. Stylish kitchens, I’ve observed, feature a single shelf of pristine autographed cookbooks from the likes of Jacques Pépin, Barefoot Contessa Ina Garten, and other television celebrity chefs. They do not have Hey Mom, What’s for Supper?, a 1982 yarn-tied collection from McCulloch Middle School; Tried and True: Recipes From the Wadley Regional Medical Center Auxiliary Tasting Luncheon; or a blue Junior League of Houston cookbook with the back cover chewed off by our counter-surfing Lab who smelled the banana-bread drippings on page seventy. Out with them! When am I actually going to serve “Meatball Yummies,” “Polish Mistakes,” or “Hester’s Horseradish Salad,” a dish requiring Eagle Brand condensed milk, crushed pineapple, horseradish, cottage cheese, mayo, and chopped pecans, all floating in two boxes’ worth of Jell-O?

Making these recipes would require a pantry stocked with Jell-O in all colors and an assortment of items I haven’t bought in years: canned asparagus, Le Sueur peas, Velveeta cheese, Knox gelatin, mandarin oranges, oleo, yeast cakes, Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup (essential for any recipe with the words “supreme” or “divan” in its title), Miracle Whip, Cool Whip, Mrs. Tucker’s shortening, Pet evaporated milk, marshmallows, and more maraschino cherries than you might think.

But as I thumb through the pages one last time, I pause. How can I discard these lovingly collected recipes? They are now historical. The earliest ones, such as the 1943 edition of Irma S. Rombauer’s Joy of Cooking, reflect Great Depression–era economies and World War II rationing (in her preface Rombauer refers to “our mighty weapon, the cooking spoon”). They are also often humorous. “If you can’t find pinto beans, canned pork ’n’ beans will do nicely,” reads one. Another recipe, titled “Danish Dessert,” employs four cups of that old Scandinavian pantry standby: crushed Kellogg’s Corn Flakes.

Some, from my hometown of Texarkana, suggest the fifties cook’s longing for more exotic climes. If you lived in East Texas and couldn’t escape to Colorado in the summer or go sailing in the Caribbean during the holidays, you could just whip up some “Tropical Snowballs” and pretend. Or how about something recalled by a husband stationed in Italy after the war and labeled “Resota”? And then there are the directions for “Neopolitan Spaghetti,” which note “1 Tbsp. olive oil for flavor (optional).”

The church cookbooks in my pile have a decidedly denominational slant. The Baptist ones invariably include a recipe for a happy home (requiring ample cups of love, loyalty, forgiveness, hope, and tenderness, several quarts of faith, and a barrel of laughter). I also see “Scripture Cake,” which can be baked only by those with solid training in reciting the books of the Bible in order and a taste for figs and honey (“4 1/2 cups I Kings 4:22,” “2 Tbsp. I Samuel 14:25,” and so on). No cooking sherry required in these recipes. In Holy Chow, my St. James’ Episcopal (Texarkana) cookbook, by contrast, I find “Eggs Arnold,” with sausage, cheese, spinach, and bourbon. The recipe concludes with a confession that it was concocted one Saturday morning using ingredients on hand.

But the real reason I can’t part with the old cookbooks is the names associated with the recipes. They are all people from my life. There’s orange date cake from Veva Nicholson, the director of First Baptist’s primary Sunday school department, who never doubted that eight-year-olds could memorize enormous passages from the King James Bible. There’s sweet potato casserole from Miss Edna, whose hair matched the dish. The front room of her house was the beauty parlor where I had many a smelly perm. Even the sounds of the names attached to these recipes—Virene, Edna Earl, Thelma, Winnie Mae—offer a nostalgic trip to a gluten-filled time when most women banked their reputations on what they served their company, brought to potluck dinners, and carried to their sick friends. I toss them back in the “keep” pile because they speak not only of people who had a hand in my upbringing but of spontaneous hospitality and generous gestures that shouldn’t be lost.

Creating that warm sense of hearth and home requires more than a recipe, of course. Some people do it with apparent ease. I have a friend who still sets the breakfast table for her family as if they were honored guests. I think my father grew up in such a household. “Do you fancy squirrel, Reverend?” my Victorian-era grandmother Susie is reported to have asked the family’s luncheon guest as they chatted politely in the parlor while servants laid a bounteous platter of the fried critter, tented with linen cloths, on the sideboard. “Madam,” the Methodist minister replied, “I’d as lief eat a rat.” Lunch was delayed a bit while chickens were quickly slaughtered in the backyard.

I don’t have my grandmother’s recipes for fried squirrel or chicken. Despite the foodie injunction to “eat local,” I have yet to see squirrel or coon and collards on a hip urban menu. My grandmother died the year I was born, so I never stood beside her on a stool in the kitchen with a dusting of flour on my nose observing the sifting, stirring, and kneading that created the traditions of a hospitable home. I knew her sister, my great-aunt Mattie, and Mattie’s seven children, grown-ups when I met them: Ben, Paul, Mary, Ruth, Carrie, Susie, and Forrest (known as “Son” and eventually “Uncle Son”). Their childhood home, in Clarksville, gave me an indelible image of East Texas hospitality in its purest state.

That image is coconut cake.

The fluffy cake, with its luxurious icing, moist crumb, and freshly grated, lightly toasted coconut is displayed on a glass stand with one slice already missing, which means it’s not going to the church or to a bereaved friend. It’s for you. Even if our relatives hadn’t heard we were coming, someone had always just baked a cake. And we could eat it regardless of the time of day.

But it wasn’t just the cake. It was my cousins’ indomitable party spirit and wit, which remained undaunted even during the Depression. When they couldn’t afford food for a crowd, I was told, they made everybody smile by putting out a tray of salt and a gallon pitcher of water, inviting guests to have a finger lick of salt and then dance themselves thirsty enough for a gulp of water.

With such a lineage, how did I become the sort of woman who, thinking only of her family of five, headed to the store, bought five pork chops, and simply couldn’t cope when an unexpected guest arrived? The traditions of food and open table derailed when my father, a reporter at the Texarkana Gazette, married my mother, a reporter and women’s editor in the same newsroom. As newlyweds, they ate the large noon meal then known as “dinner” in East Texas at a boardinghouse not far from the Gazette offices. They worked to fill not one but two editions of the local paper—the Gazette in the morning and the Daily News in the afternoon. Exhausting. If they entertained, it was with cocktails and cigarettes.

While other women in town were building their reputations on “Tropicana Chicken Divan” or “Make Ahead Company Nut Thins,” my mother openly admitted that the worst day of her life was when I learned that most children did not eat Cheerios for supper. She had no illusions about herself as a cook. She didn’t even figure in a gossipy discussion of Mrs. Edwards’s unfortunate pale fried chicken or that Yankee newcomer who—heaven forbid—put dark meat in her chicken salad. When I asked my brother what foods he remembered from our childhood, he replied, “None. I could have only concocted an oxygen sandwich from what was in our refrigerator.” If the supper table in our home was lively, it was the insider newsroom conversation, not the food, that spiced things up.

In my Baptist cookbook Favorite Recipes From the Kitchens of Our Senior Adults, “Mock Filet Mignon Supreme” has my mother’s name attached to it, a fact that surprises me to this day given how, at family gatherings, my mother was always relegated to the simplest of kitchen tasks. When she mindlessly daubed the cranberry molded salad with chicken fat instead of the homemade mayonnaise, she was demoted to picking up rolls at the local bakery. She cooked, but her heart was never in it, and she left me with no fading handwritten recipes for tea party cucumber sandwiches and, for that matter, no food traditions to uphold. I have no recollection of this mock filet mignon ever being served in our home, and I suspect she kiped the recipe from the Wadley Hospital cafeteria while volunteering in the emergency room.

My brother and I didn’t have rickets, so I’m sure our nutritional needs were met. Our mother did make a decent pot of chili. She also served a dish I knew as “Hoppy Chom Pulley.” I think I’ve seen something like it in a few of my Southern cookbooks under the more accurate name “Hoppin’ John Poulet.” It was a concoction of chicken, black-eyed peas, tomatoes, corn, and okra. I remember it mostly because of the slimy okra, which my father ate with such relish that I could hardly remain at the table. When I protested the slime, he’d say, “You know, okra slips down your throat so fast that if you feed it to a dog, he’ll bite the dog behind him” (for stealing his treat). I wanted to feed a lot of what was served at our table to our dog.

Fortunately, the more domestically talented women in Texarkana were generous. Mrs. Shipp, who lived next door, felt so sorry for my father that she routinely doubled her chicken and dumplings recipe and sent over what we called “care packages.” She also made green-tomato chowchow, for which my husband developed an addiction on later visits to my parents. Miss Fanny Eldridge, across the street, loved to bake, and she often brought us her chocolate cake bountifully laden with cherries. The McDaniels treated us to festive champagne and a plateful of champignons et oeufs on Christmas morning (or was it New Year’s?). And religious devotion was not the only reason we spent so much time at the First Baptist Church. The Baptists were usually good for at least two free meals a week.

My mother, a child of poor German immigrants, was unfailingly lavish in her attention to the truly needy. She offered rides to strangers at the bus stop and sometimes, without consulting us, gave our back bedroom and second bath to out-of-town relatives of patients receiving treatment at the hospital. Generosity, in her book, had nothing to do with indulging what she regarded as her already indulged family. I admired her intelligence, financial acumen, and ability to puncture pomposity in all forms. But I still wonder what it would have been like to grow up in a house I saw described in a recent obituary. “Grannie’s house,” it read, “will always be remembered for the smell of chocolate, pecan, and coconut pie filling the air and divinity so light and fluffy it was like eating a cloud.”

I wanted more of that for my family, hence the overstuffed pie safe. I’ve worked most of my adult life and often rely on my husband’s sous chef skills, but I still think it important for women to occasionally appear in our historical roles, providing comfort in the kitchen. For lack of a model, I had to improvise. Many of my friends came to their married lives already equipped with signature dishes; if there is a birthday in my friend Anne’s family, for example, every member hopes not for cake and candles but for her banana pudding, its creamy custard filling topped by the airiest meringue. Anne’s mother’s dinner rolls were so prized that a few years ago, when her mother was approaching one hundred, Anne gathered all the daughters-in-law to videotape a training session on how to make them.

Cousin Paul’s daughter, another Anne, still has the handwritten recipe notebook that contains my great-aunt Mattie’s chess pie and a legendary jam cake as well as the coconut cake and “Seven Minute Icing” of my childhood visits. All of them call for enough sugar to make your teeth ache. The 10-cent composition book from Duke & Ayres, with its fragile pages and careful script, is an important link both to the family’s generous habits—sometimes their guests stayed all summer—and also to their stories. Whenever a descendant makes the boiled custard (homemade eggnog), a recollection of times past resurfaces. The recipe makes no mention of bourbon because that ingredient was traditionally served in a pitcher beside the punch bowl, to be dispensed according to the partaker’s tolerance. Of course, tolerance was frequently misjudged, and the windiness of the Christmas blessing by Cousin Ben after an afternoon of boiled custard reportedly caused Mary Deavers, a helper in the kitchen, to comment, “Lawd, ain’t nobody gonna hear that prayer.”

Alas, all happy families are not alike. If you asked my three grown sons what special dishes they anticipate during the holidays at Mom’s house, I think you’d draw a blank stare. It isn’t that I’m not a pretty good cook or that I didn’t cook during their childhood. I did. I have brined and roasted a turkey at Thanksgiving and fussed over standing rib roast at Christmas every year of their lives. I have made Yorkshire pudding, squash casserole with Ro-Tel, and mountains of mashed potatoes; I have peeled and meticulously deveined grapefruit and oranges for ambrosia. What do they remember? The gumbo that I pick up on Christmas Eve from the S. & D. Oyster Company and the Sister Schubert’s dinner rolls from the freezer aisle at Kroger. My homemade chocolate chip cookies, made with real butter, were always too full of nuts and too crispy; they preferred chewy with no nuts, even better if they were packaged Chips Ahoy.

Two of the three will express some pleasure over a lemon Jell-O cake, a specialty that requires no culinary skill other than combining a box of yellow-cake mix with a box of Jell-O. My sons have called it “white-trash cake” ever since they spotted a variation of it in the Elvis Presley cookbook I picked up years ago at Graceland. My sons knew friends with kitchens that always seemed to have a pantry stocked with snacks, a ham and a turkey waiting to be sliced for sandwiches, or tasty leftovers from a huge party—a far cry from the stingy stir-fry I might make to use up the pork chop one of the boys had eschewed the night before. My mother is still very much in me. If required to draft my obit, will my sons mention the aroma of burnt toast or the mess I made when I left an egg boiling while I was engrossed in a book?

My grandchildren do stand on a stool beside me in the kitchen and don’t seem to mind that we are making blueberry muffins or pancakes from a box mix (for the record, I add fresh blueberries). If their praise is lavish, I suspect it’s because I bake their muffins in silly rubber muffin cups with legs. But when they’re a little older, I hope we’ll tackle that coconut cake, with its Seven Minute Icing. We’ll share a slice, and then we’ll display the rest on a glass stand on the kitchen counter, in case someone drops by.

- More About:

- Texas History