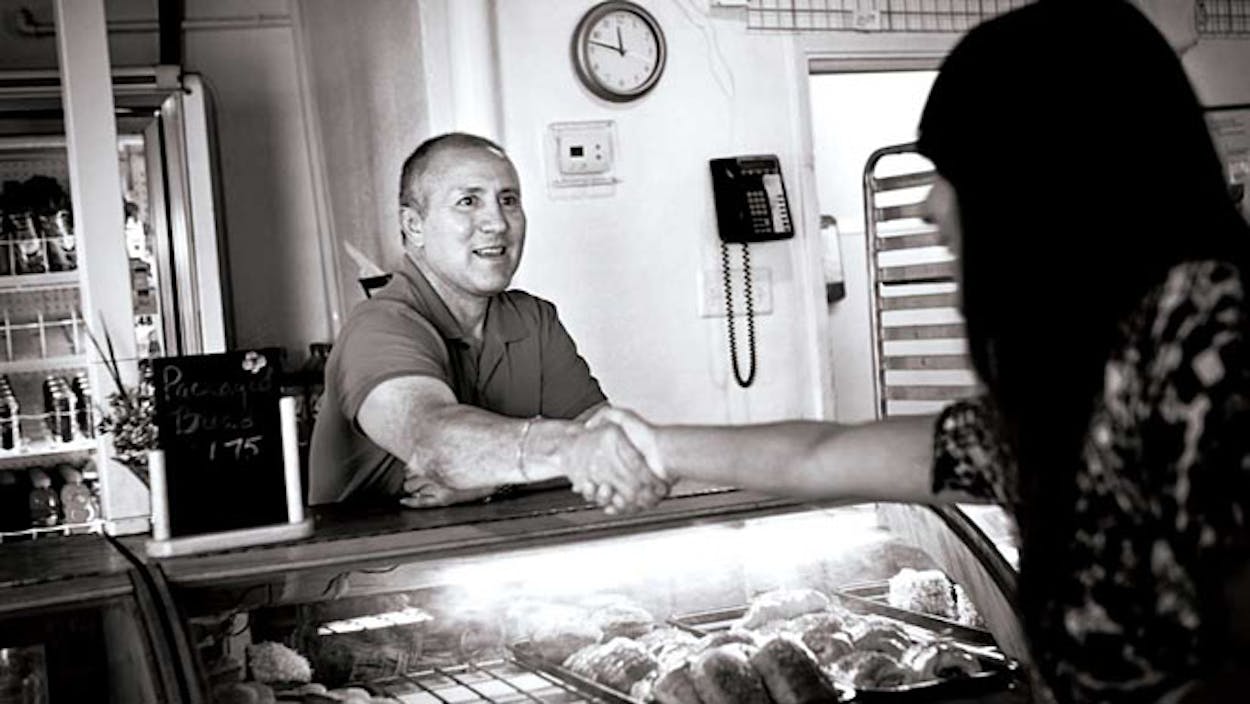

Marquez, who’s lived most of his life in El Paso, spent his childhood at a bakery his parents purchased in 1971, when he was five. Today Marquez owns and operates two of the family’s three bakeries (his brother owns the other), which are known to have some of the best pan dulce in the area.

I was a little kid when I started working in the bakery—and I’ve never done anything else. Forty-something years later, I’m still hanging out in the kitchen.

My dad grew up working at a bakery too, in Mexico. And he even baked his own bread and pastries, in an adobe oven in his house, and sold them from a basket on the street in his hometown of Sombrerete, Zacatecas. He knew his way around some dough, so after my parents settled in El Paso, they bought a little place called Bowie Bakery—really just a tiny little room—at the corner of Seventh and Park, in the oldest neighborhood in the city. At that time, it mainly sold cookies and pastries, but my dad wanted to bake his recipes from back home.

I was about five and the youngest of four kids when my parents started their bakery. My parents were really struggling back then. Well, I guess we all were. We lived twelve miles away, outside El Paso, and we didn’t have a car. We took the bus back and forth. The bakery would close at ten at night, and sometimes the bus driver would wait on us to close so we could catch the bus. Other times we would all sleep on the floor there. My mom would put blankets and pillows down on flattened cardboard boxes for us to sleep on, and we’d sleep for a few hours, then my dad would get up at three to start mixing the dough. That place was our business, our living room, and our bedroom. Heck, it was my nursery.

Slowly, things got better. Our products really caught on, our typical Mexican pastries. The people of El Paso began to love our homemade conchas, gingerbread piggies, and empanadas—the very things my dad grew up baking and selling on the street.

I watched everything that went on from my perch in the kitchen. My dad would have me stand on a box and give me scraps of dough to play with. I would put on this enormous apron and mirror what he was doing. He would roll the dough for me a little bit and have me finish it. I would make whatever he was making but in miniature size. I was making the samples, you see, but to me they weren’t just samples. To me, I was one of the bakers. And if a customer wanted to buy the samples, I would get mad because my dad was actually selling the things I baked. I wanted to eat them! Dad taught me how to work—and not eat up all the profits, I guess. It was my first lesson in business.

As I got older, I began to realize that this bakery, this place filled with huge machines and wonderful smells, was not just something for me to do after school—it was my future. Through the years leading up to college I did all kinds of jobs there: I baked, I decorated cakes, I worked in the office. I learned everything I could. Eventually I became more interested in the business side, and I decided I wanted to run the place one day. So after studying management at the University of Texas at El Paso, I got to do that.

When my dad passed away several years ago, we got letters from all over—even President George W. Bush sent us a letter of condolence. My dad left me the bakery, and I run it just the way he did: with love. A lot of our bakers have been with the family fifteen or twenty years, and they make everything by hand, the way my dad trained them to. For example, we make a Mexican puff pastry called paloteado, which is formed by rolling out the dough and folding it over and over again. It has so many layers, it looks like

an accordion.

Most days I arrive at work a few hours after the doughnuts are made. The bakers get there at three, just like in the old days when we slept on the floor. When we open, we have everything ready, hot and fresh, because there are people lined up to eat it. I had a stroke a few years ago, so I don’t bake much anymore. But first thing every morning I do a run through the bakery, talk to the bakers and see what they’re up to, make sure everything is okay. Basically I’m quality control—after my childhood, I’m the best there is. I know what everything is supposed to look like when it’s coming out of the oven. After I talk to the bakers, I place the day’s order for ingredients. And then I get to chat with the customers. They tell me that when they walk in they smell the butter and sugar and it makes them feel like a kid again.

As told to Jason Sheeler on April 2, 2013

- More About:

- Working Life