At La Morena, you wrote your own order. This was how I learned to scribble mine: reg. – kitchen sink – wet – mild – Wallace. And Lord help you if you screwed it up. Greg Revelez, the owner of this tiny Tex-Mex joint, was the orneriest—and to many, the most beloved—restaurateur in Andrews, my hometown in the heart of the Permian Basin oil patch. You could be sure that Greg would give out to you if you left off your name or the size of the burrito you wanted or, worst of all, you forgot to include your spice preference. That pretty much guaranteed you were gonna get burned.

After you jotted your order and tore it from the notepad on the counter, you took it past the bright red “EMPLOYEES ONLY” sign into a small kitchen. There, you traded holas and smiles with Maria, who was always bustling over bubbling pots of carne guisada, her arms dusted with flour from tortilla-making. Using a wooden clothespin, you hung the ticket on a piece of twine strung up over a slow cooker full of asado de chile colorado. Next, you opened the oven door and pulled out a warm basket of fresh, paper-thin chips. After grabbing a bowl off the counter, it was over to the fridge, to scoop salsa out of two big Tupperware containers: one red, one green. I preferred what Greg called Christmas, two scoops of mild red with a plop of the fiery green in the middle.

Once you’d dropped these off at your table—there were maybe twenty seats in the place—you fetched your own drink. Big plastic glasses were stacked by the dishwashing sink and ice was scooped from a deep freezer located in a back room filled with Greg’s granddaughter’s old toys and other sundry artifacts. Cold beverages were snatched from the ancient, Pepsi-branded sliding glass doors. There was Mexican Coke and glass-bottled Fanta. On the bottom row was tea and lemonade, which Greg made himself and served in old milk or juice jugs. I grabbed one of each to fix an Arnold Palmer.

About the only thing you didn’t do yourself was bring out the food. When a few orders were ready, Greg would rise—grudgingly, it seemed—from his designated seat at the table nearest the kitchen and would return bearing steaming plates of enchiladas or chiles rellenos or bowls of caldo de res, but, for the high school kids, mostly burritos. This was when you’d pray that you hadn’t messed up your order or that your buddies hadn’t conspired with Greg to get you burned.

Being “burned” meant having your burrito made superhot with one of the specialty salsas Greg would tote home from trips to San Francisco. The unsuspecting victim would take a bite or two, and then a few seconds later you could almost see smoke pouring from their ears. Most of Greg’s high school customers, myself included, had been burned at some point. It was an initiation of sorts—a rite of passage usually instigated by someone informing Greg that he had a new customer. Getting burned was part of becoming a regular at La Morena. And it was always wise to take that first bite with caution.

Spice and heat were part of the culture at Greg’s. On the rare occasions he did take your order, he always asked if you wanted your burrito “spicy” or “Gerber.” I tend to like my food on the warmer end of the spectrum, but at La Morena, “spicy” was often too much for me to handle, especially when I had football practice a few hours later. I’d hang my head as I told him, “Gerber.” He’d respond with a disappointed grunt.

At some point, another tradition formed around Greg’s love for peppery heat: the toothpick challenge. Anyone who was curious about the infamous bottles of ghost-pepper salsas Greg picked up on the West Coast was allowed to dip a toothpick into the liquid and taste it. (Greg refused to sell the stuff to customers under eighteen, for fear of what they might do with it.) For most who tried a “toothpick,” that was all their tongues could stand. But one brave or very dumb soul decided to attempt several in a row. This quickly evolved into a contest to see who could do the most toothpicks in a row. Names were recorded on a piece of paper, with tally marks indicating how many each person had managed. Eventually, someone would come along and try to set a new record. I was there for one of the unsuccessful attempts.

I had brought my friend, Sergio Flores, to lunch at La Morena. He’d never been there before and asked about the list of names taped up behind the counter. After I explained the toothpick challenge, Sergio was sure he could beat them all. Sergio was a big dude, a lineman on the football team with an ego to match. Greg brought out a special bottle. Sergio dipped a toothpick then licked it clean. Before he could finish his second dunk, his face turned red. He started to sweat. His face screwed up in pain, as if he’d been shot in the belly. He ran outside to the parking lot and puked. Sergio’s name never did make it onto the list.

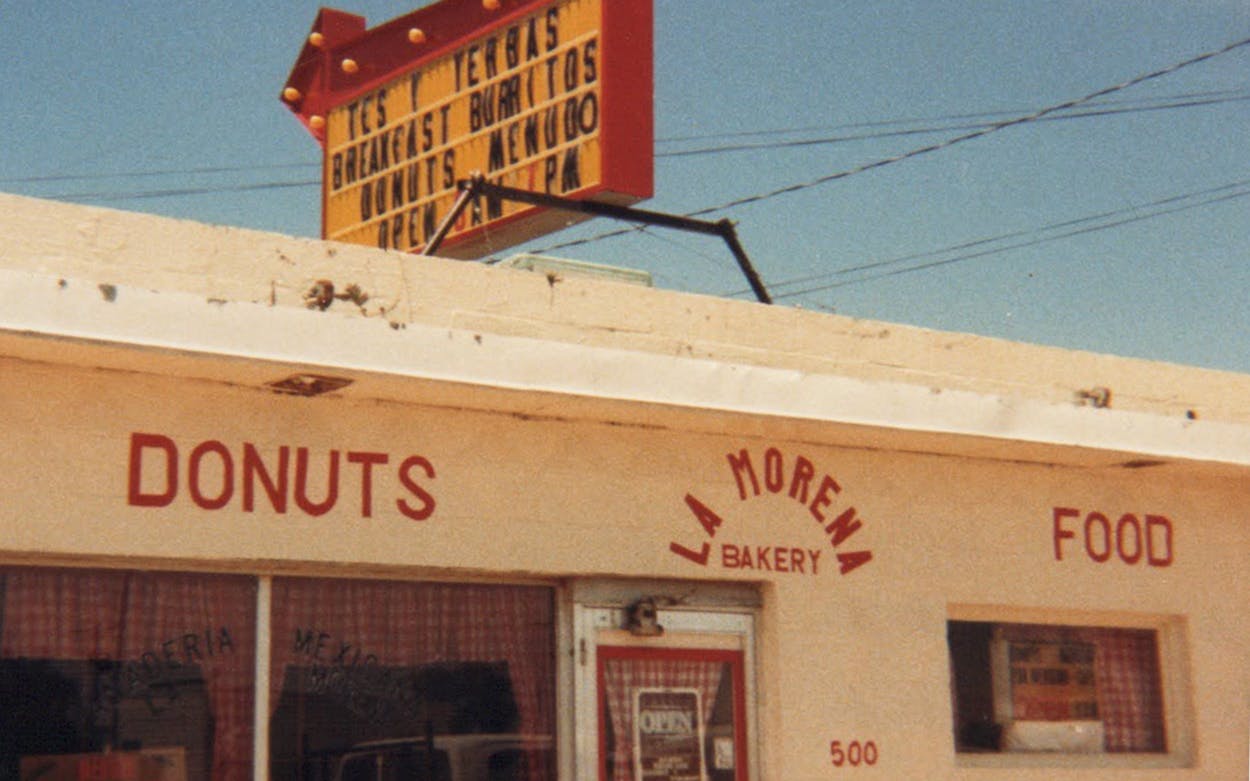

These traditions—toothpicks, waiting on yourself, getting burned—all evolved naturally over the course of four decades. Greg’s mother and aunt opened La Morena as a bakery in 1982. Greg joined them shortly after and eventually took over the business. He transitioned away from baked goods, he said, because he grew tired of waking up at 3:30 every morning. Greg’s mother, Santos Revelez, played a huge role in shaping the menu that La Morena would use for almost forty years. “Ninety-nine-point-one percent of the recipes we used came from my momma,” Greg told me.

Greg’s parents had been migrant workers, and he’d grown up all over West Texas, with stints in Chicago, Idaho, and California. The Revelez family had picked cotton in Lamesa and Tarzan, and when one crop ran out for the season, they’d leave for the next: carrots, potatoes, onions, cucumbers. Because they were constantly on the move, Greg once attended nine different schools in a single year. Though there were hardships and long hours in the fields, Greg enjoyed his itinerant childhood. He said it was peaceful.

After high school graduation, Greg moved to San Francisco, where he lived and worked in upholstery for 25 years. Greg moved to Andrews in the early eighties because he wanted to be near his aging parents. Santos was cooking at La Morena, so Greg joined her there. He remembers how fond the customers were of his mother—not just of her cooking. “A few of the guys who came in called her Mom,” Greg said. “They would eat their food in the kitchen with her.”

Santos had passed by the time I started spending my high school lunch breaks at La Morena, but her recipes lived on. All the traditional items on the menu were excellent, but I was most fond of two slightly unusual dishes she created: the wet Kitchen Sink Burrito and the Mexican Burger. The Kitchen Sink was so called because the burrito included “everything but the kitchen sink”: refried beans, french fries, rice, cheese, and some sort of cubed meat, though exactly what kind varied day to day. The brown gravy that smothered the whole thing made it “wet.” The Mexican Burger had the same gravy poured over an open-faced cheeseburger served with a pile of refried beans. I’d put either dish up against the best thing I’ve eaten anywhere else.

But La Morena wasn’t just about the food. Customers wanted to be there because Greg was there. If he wasn’t holding court—usually discussing the latest Andrews Mustangs game—he’d be in his seat reading the Andrews County News while Judge Judy or a telenovela or Maury played on mute on an old TV in the corner. Greg was dapper in a purely West Texan way. His gray-white hair was always neatly combed back in an understated pompadour. He sported a Clark Gable mustache. And every day he wore a crisp, solid-colored pearl-snap shirt tucked into his jeans. In fact, I remember going to a thrift store in high school and buying a couple of pearl-snaps because they looked like shirts Greg would wear.

Greg’s grumpiness was the stuff of legend. You almost felt like you should apologize for inconveniencing him with your patronage. The whole order-for-yourself thing had started because, as he told me, one day he was too lazy to wait on a regular. “Here,” he told him, “write your own damn order.” Not everyone found this system charming. The health inspector, for one, didn’t. (Greg ordered everyone to stay out of the kitchen if an inspection was imminent.) And once, an old woman came in and sat wide-eyed as she watched other customers come and go from the kitchen with chips and salsa. Greg caught her look and told her, “Stick around, honey; we’ll teach you how.” She didn’t come back.

There was also a softer side to Greg. You’d see glimpses when little kids would come into the restaurant with their parents and run to Greg for a big hug. He wasn’t boastful about his good deeds or kindness, but it wasn’t uncommon to hear that he had helped a family member or customer when they fell on hard times. It was well-known that under that gruff exterior, Greg was a good man.

Mostly, though, he did things his own way. For instance, the burritos came in two sizes: super and jumbo. I could never remember which one of the two was smaller, so I wrote “reg.” on my ticket. La Morena was also cash-only, and prices seemed to fluctuate with Greg’s mood. Ten bucks might cover you one day, and the next day you’d be a few cents short—even though you’d ordered the same thing. Whatever money Greg made, it didn’t seem like too much of it was being invested back into the ramshackle building.

The decor might be described as “eclectic.” A large print of da Vinci’s Last Supper hung on one wood-paneled wall. Across the dining room, a framed painting of two reclining jaguars kept watch over one of the red vinyl booths. And there were a few yellowing pieces of paper taped to the walls with sassy sayings, like this one: “If you are grouchy, irritable, or just plain mean, there will be a $10 charge for putting up with you.” (I always thought the sign could be applied to Greg as much as his customers.) The building itself was cinder block and sun-faded, with one big window facing Main Street. The restaurant had once boasted a drive-through window, but after Greg got divorced, his ex-wife bought the empty lot next door and forbade anyone from parking or driving on it. During the peak lunch-hour rush, the tiny caliche parking lot out front turned into a crowded mess of mud-spattered company trucks and gleaming high schoolers’ vehicles.

After most of the restaurants in Andrews banned smoking, La Morena remained one of the few holdouts. As high schoolers, we’d sit in a booth and light up our Camel Blues—for the nicotine kick, sure, but mostly because it felt transgressive, made us feel like adults. Then one day, without warning, the red plastic ashtrays disappeared from the tables. And behind Greg’s seat appeared two new signs: “NO SMOKING” and “PROHIBIDO FUMAR.” Greg, who had smoked a pack a day for some fifty years, had quit cold turkey. “If you’re smoking in here,” Greg warned us, “you’d better be on fire.”

Turns out the change was better for his health and his bottom line. More families started to dine inside after the clouds of tobacco smoke dissipated. My family had been ordering burritos from Greg’s since before I could remember. I had grown up with my dad telling stories about the place, like the first time he tried menudo. Back in the mid-eighties, my dad was working on a roustabout crew in the patch. He was younger and wilder then and showed up to work one Saturday morning still sloshed from his Friday-night antics. His crewmates knew he’d be worthless that day if they didn’t do something, so they took him to Greg’s. They slid him a bowl of the red, broth-y stew. My dad took one bite and pushed it away. “There’s no way I’m eating that,” he told them. “Look, güero,” one crewmate said, as he added chopped onions and cilantro, tossed in some tortilla strips, and squeezed a lemon in. “That just changed the whole flavor,” my dad later recalled. He downed the whole bowl and was able to “make a hand” that day. Two decades later, I would find myself in the same booth, eating the same menudo, trying to ease a throbbing head before work.

This intergenerational connection to La Morena went well beyond my family. Alison Revelez, Greg’s granddaughter, is the same age as me. She and Greg were close. From the time she started kindergarten till she started driving herself, Greg took her to school in the mornings and picked her up each afternoon. Every regular knew Alison, had watched her grow up in the restaurant, playing in the back room or chatting with diners up front. When school was out, and when she was old enough, Alison started working there as a waitress.

At first it was strange not to write your own order, but it proved a welcome change. Alison was friendly and warm, the perfect foil to her grandpa’s surly demeanor. After graduating high school and leaving town for college, Alison and I both came home to work during the summers. She was at La Morena, and I was working on an electrical crew. I’d arrive for lunch in a sweat-drenched T-shirt, sawdust sticking to my arm hair, smelling worse than a locker room, but Alison greeted us all with a smile. I probably ate more meals at La Morena during one of those summers than I have at any restaurant before or since. But those days are long past now. Alison met the love of her life and settled in a town near Abilene. “When Alison left, that took a big chunk out of me,” Greg told me. But he knows that’s just the course of life, and he’s happy for her. On Alison’s wedding day, he walked her down the aisle. I was told he even shed a tear.

Earlier this year, Greg shut the doors of La Morena. The restaurant had weathered four decades of booms and busts in the oil field, but the business had struggled through the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially without a drive-through. Greg is 82 now, and one of his knees has been giving him problems. He needs surgery, and he felt like he couldn’t keep up with the restaurant anymore. “I don’t miss getting up at five o’clock,” he told me. “But I really miss the people.”

I went back one last time this summer. Alison was helping Greg sell off the equipment and told me I should come grab some mementos. I bought a couple of the plates they used to serve Kitchen Sinks and Mexican Burgers. I stared for a while at the jaguars and the disciples sharing their last supper, but in the end, I asked Alison if I could have the coffee-stained piece of paper stuck to the wall with the quip about grouchy customers. It seemed like the perfect reminder of Greg.

Andrews won’t be the same without Greg’s restaurant. But this past weekend, while I was in town for a funeral, I noticed a sign in its window: “Abierto.” A new taqueria had just opened. At some point, I’ll stop in and try it. But today I’m missing La Morena.