When the Adolph Coors Company of Golden, Colorado, decided last summer to expand its network of beer distributorships into South, Central, and East Texas, it was almost as if Coors had announced plans to award perpetual-motion money machines. Never in the history of Texas business would so many try so hard to win something so ostensibly ordinary as the opportunity to sell beer.

The Coors Company was besieged with more than 4000 applications for the new distributorships, including entries by John Connally, Spiro Agnew, Allan Shivers, a string of professional athletes, and several men who have ridden rocket ships to the moon. Soon they and hundreds of other celebrities, politicians, businessmen, competing-brand distributors, and ordinary beer drinkers across the state and around the country found themselves in the midst of a competition many would later describe as the most grueling thing they’d ever endured.

They answered exhaustive personal, political, and psychological questionnaires. They compiled vast amounts of valuable local market data. They estimated. They interviewed. They sweated. And all the while, they eyed each other nervously as rumors about who already had a distributorship “in the bag” flew from tongue to print.

For all but a few, the effort and worry proved fruitless. Between mid-August and the end of December, Coors gradually revealed the selection of 29 groups of men to distribute its beer in Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Waco, and eighteen other towns from Laredo to Longview. As it turned out, many of the high and mighty previously rumored and/or reported to have won a Coors distributorship wound up empty-handed. Former Vice President Agnew even withdrew his application in the wake of adverse publicity.

Among the chosen few were a heavy sampling of astronauts, professional athletes, and men with useful political connections, including a number of present and former government officials. Contrary to its own publicly quoted statements, Coors also chose several men with prior experience in the beer industry, including at least five who had previous connections with the Coors Company itself. Of the 29 distributor groups, all were composed of political conservatives; only five included men with Spanish surnames; and none included women or blacks. But more surprising, the majority of new distributors were not even residents of the areas they were designated to serve.

These developments immediately provoked a great deal of controversy, ill will, and—not incidentally—free publicity. Local and national media played up the choice of men like moonwalker Alan Shepard and ex-Dallas Cowboy star Bob Lilly. Frustrated applicants all over the state alleged that the whole selection process had been predetermined from the outset, and that Coors had simply used the opportunity to collect some free market information. Black and Mexican-American leaders leveled charges of racial discrimination in the awarding of distributorships, and two Chicano groups announced boycotts of Coors. Others, including many successful applicants, simply expressed befuddlement over the types of criteria Coors used in making the selections. Meanwhile, executives of other leading national and Texas beer companies braced themselves for what one predicted would be a marketing “Battle of the Trenches.”

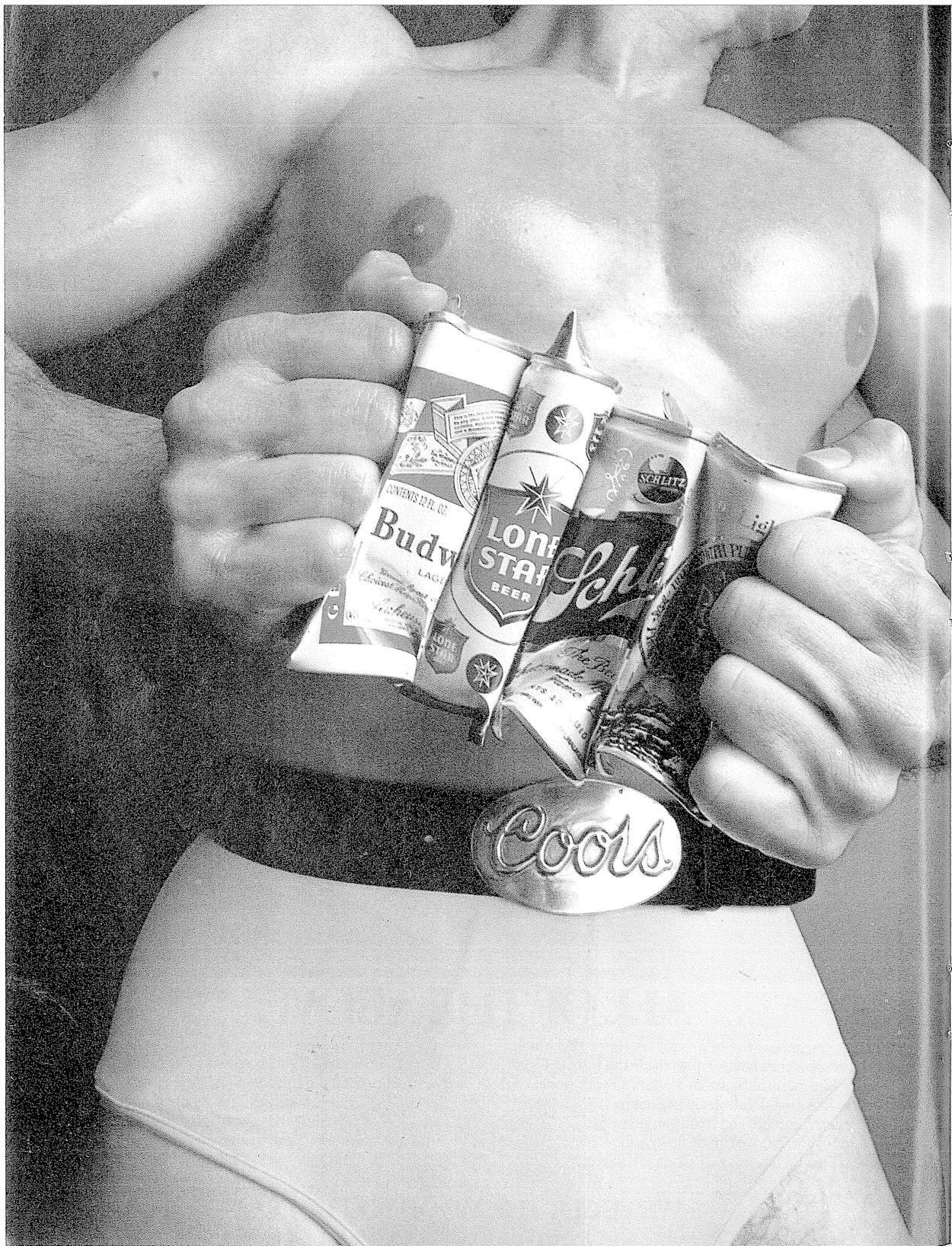

For the Colorado-based brewer, this brouhaha was hardly new. Though known in business circles as a “super straight arrow” organization, Coors’ iconoclastic financial and marketing practices have won it a reputation as the “brewery that breaks all the rules.” The company also has a long history of political turmoil revolving around the arch-conservatism of the founding family, and a standing feud with the press. Typically, its response to allegations of preselecting its new Texas distributors and favoring trustworthy conservatives continues to be a repeated “no comment.” But despite certain difficulties here and in other parts of the nation, Coors has had few problems selling its beer to consumers. Although Coors markets in only eleven western states, it is the country’s fourth-largest brewer, behind Budweiser, Schlitz, and Pabst, who distribute their beers across the country and around the world. In ten of its eleven marketing states, Coors is the number one selling beer, with market shares ranging from 40 to over 70 per cent. The eleventh state is Texas, where Coors already ranks third, ahead of such home brews as Pearl and Lone Star, despite having penetrated only one-third of the total market area. And all this sales success has been accomplished with less than half the paid advertising spent by the other leading brewers.

Coors, it seems, need rely only on word-of-mouth and the thousands of dollars of free publicity generated by aficionados across the country. It is, as has been written so many times, the favorite beer of Paul Newman, President Ford, Henry Kissinger, Kissinger’s bodyguards, Ethel Kennedy, the Boston Red Sox, the Miami Dolphins, and thousands of other less prominent “Coors runners” from coast to coast. In the East, where Coors is not officially marketed, beer drinkers pay as much as $15 a case for cans and bottles of the smuggled brew. A recent article in the New York Times described Coors as “the most chic brew in the country,” and it even remains the top seller in Chicano neighborhoods despite the company’s checkered history of minority relations and the diligent efforts of boycott leaders.

Coors’ recent expansion in Texas, while no doubt increasing the Coors’ myth, has also raised a number of intriguing questions about the way the Colorado brewer does its business. The most persistent questions concern Coors’ new distributors. How were they chosen? What are the stakes? How good a deal did they get after all? But before these are answered, an even more fundamental question must be considered: what makes Coors so special?

Most of the company’s competitors and a great many plain old beer drinkers attribute Coors’ enormous popularity to a kind of Rocky Mountain “mystique.” They say that Coors, or “Colorado Kool-aid” as it is sometimes called, is actually just another light, rather tasteless American beer; only its unavailability—the fact Coors is so hard to get in most parts of the country—makes it so much in demand.

Company president Bill Coors naturally takes issue with this point of view. “There’s no mystique about Coors’ popularity,” he has said on several occasions. “It tastes better than other beers, that’s all.” However, repeated blind taste tests sponsored by various newspapers and magazines have cast considerable doubt on whether the celebrated Coors’ taste differs at all from that of other premium American beers. In most tests, even prideful, experienced beer drinkers have been unable to distinguish Coors from such brews as Schlitz, Bud, and Miller High Life. Still, there are several things about the beer and the company that may make Coors leave a distinctive—and not always favorable—taste on the palates of beer drinkers and non-beer drinkers alike.

One is the emphasis on what Coors proudly calls “quality control.” The company is truly fanatic about it on several levels. For example, Coors has a longer brewing process and spends more on beer ingredients than any other major American brewer. Its barley is a special Moravian strain grown by its own special farmers with special certified seeds. Its rice and hops are also the best a brewer can buy, while its water is said to be “pure Rocky Mountain Spring Water.”

Part of the difference—if any—in Coors’ taste may be attributable to using slightly less of the tangy ingredients (malt and hops) and slightly more of the bland ingredient (rice) than is common among other leading American and foreign brewers. It is thus light-bodied, but it is not a “lite.” Coors has the same alcohol content (3.5 per cent by weight, 4.5 by volume) and calories (137 per 12-oz. can) as other leading beers like Bud and Schlitz. Coors does, however, have a longer fermentation and aging process. By means of chemical additives, some major American brewers have reduced their entire brewing time to less than three weeks. Coors takes about 70 days to complete its total brewing cycle, and nearly two months of that time involves the aging process alone.

At no time is Coors pasteurized, as are almost all other U.S. beers. Pasteurization involves killing the yeast culture by means of heat and thus may alter the flavor of the beer. According to the New York Times article, Coors stopped pasteurizing its beer almost twenty years ago when the company determined that “heat is an enemy of beer.” Consequently, Coors should be kept refrigerated until consumed in order to insure the proper taste and freshness. Unlike other brewers, Coors does not maintain a warehouse at its brewery, but immediately ships out each batch of beer in refrigerated railroad cars; the company insists that distributors and retailers keep the brew constantly colder than 40 degrees. If these “quality-control” steps are followed, the product the consumer gets in each bottle or can of Coors is tantamount to a draft beer, since it has been kept cold from the brewery to the beer drinker’s mouth. However, anyone who has traveled much in the western states may have noticed cases of Coors stacked about, unrefrigerated, in retail stores.

The Coors Company, meanwhile, is perhaps even more unusual than the beer it manufactures. In an industry characterized by the predominance of corporate giants and the folding of small independent breweries, Coors has remained for all intents and purposes a family-owned-and-operated company. In fact, it was not until last June, after receiving a $50 million dollar inheritance tax bill from the IRS, that the Coors family reluctantly decided to take public money. Even then, it merely issued Class B common (non-voting) stock, which insured that actual control of the company would remain firmly in the arch-conservative hands of the Coors family.

That is undoubtedly the way company founder Adolph Coors would have wanted it. He started the brewery 103 years ago as a young German immigrant, and passed the creation on to his American-born son Adolph, Jr., who in turn passed it on to his sons. Today, it is third-generation president Bill Coors, 59, and executive vice president Joe Coors, 58, who run the brewery’s day-to-day operations. (Their older brother Adolph III was killed in a kidnap-ransom affair in 1960.)

What the Coors family has built in the Rocky Mountain foothills west of Denver is nothing less than the largest beer-manufacturing plant in the world—capacity over twelve million barrels per year—and an almost completely self-contained $585 million corporate empire. The brewery in Golden stretches through the valley and around the side of the mountain, covering some 3100 acres in all. In addition to its beermaking crews, Coors’ local work force of 7500 includes a construction and engineering crew who are expanding the plant at a rate of 10 per cent each year. The company also owns its own bottle-making plant, rice mills, barley fields, and even some natural gas reserves to insure a power source.

It is also remarkably clean about the way it runs these facilities. Long before environmental protection became both fashionable and court-ordered, Coors established itself as the industry leader in ecology and recycling. It introduced the aluminum can way back in 1959 and has since developed and promoted a cash-for-cans program that has collected roughly 190 million pounds of discarded containers for all beer and soft drink brands, and pays out some $5 million to consumers each year. At the same time Coors has refined its engineering and production techniques to the extent that its own immediate plant wastes are merely a fraction of those expelled by other leading brewers. Coors’ traditionally sparse advertising contains no man-made objects other than the beer can itself: the rest of the picture is simply mountains and trees and bubbling streams.

This resolute environmentalism is not the picture of Coors that leaps to the minds of most organized political groups left of Ronald Reagan. Thanks in large part to the activities of executive vice president Joe Coors, the company has a reputation as being one of the most virulently right-wing enterprises in America. Joe Coors’ views first became publicized during the late Sixties and early Seventies when he served as a member of the University of Colorado Board of Regents. A contributor to the John Birch Society, he was so enraged by hippies, student activists, and other “pleasure-loving parasites,” that he financed an alternative student newspaper. Later, even that Coors-sponsored campus publication felt compelled to editorialize against him when he attempted to oust the college president because of a dispute concerning the Students for a Democratic Society. Incidents like that prompted one fellow University of Colorado regent to label Joe Coors—not the students—“the chief disruptive factor” on campus at the time.

Furious at the way the media handled the events of those years, Joe Coors decided to start his own television news service, Television News, Inc., which has thus far lost more than $5 million. One of Richard Nixon’s last official acts as President was to nominate Joe Coors for the board of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. President Ford later resubmitted the nomination, but the Senate Commerce Committee cited a possible conflict of interest, and members of the communications subcommittee tabled the nomination, effectively killing it. Among the factors working against Coors in addition to his ownership of TVN was the disclosure of two letters he had written the CPB board while his nomination was pending. One apparently sought to influence CPB editorial policy, while the other requested special CPB consideration for Coors’ attempts to set up an earth-satellite system to enhance his broadcasting enterprise.

Coors family politics have naturally had a major effect on life back at the brewery. For years black, Chicano, liberal, and labor groups have attacked and boycotted Coors for alleged discrimination in hiring practices and union paternalism. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission has twice found the company guilty of discriminating against black employees, and the Economic Employment Opportunity Commission is currently suing Coors for sex and race discrimination. According to the EEOC complaint, virtually all of Coors’ female employees are confined to secretarial-type jobs, and virtually all its racial minority employees perform semi-skilled or unskilled jobs.

Despite generally high pay and the existence of a union, ordinary white male employees do not exactly enjoy ideal working conditions either. Compelled to take lie-detector tests before being accepted for employment, Coors workers may be fired for any of 21 reasons, which include “making disparaging remarks about the employer” and doing anything “which would discourage any person from drinking Coors beer.” Such provisions presumably insure that “quality control” extends to the brewery workers as well as to the beer.

What the company would characterize as an attempt to extend the concept of “quality control” to distributors and retailers has recently landed it in serious trouble. Last fall, the Supreme Court upheld a wide-ranging complaint by the Federal Trade Commission that found Coors guilty of unfair marketing practices and restraint of trade. According to the FTC, Coors engaged in price fixing; intimidated retailers and distributors; refused to let certain retailers sell its beer; tried to maintain territorially exclusive distributorships; and attempted to keep people from selling and/or transporting Coors out of its eleven-state market area even after the beer had left Coors wholesalers. Part of the reason for some of the company’s behavior may be its concern that its unpasteurized beer be kept cold until consumed; Coors smugglers and dealers who fail to keep their supply refrigerated may spoil the taste, the company says. But this does not explain another practice discovered by the FTC: telling tavern owners they would not be supplied with any Coors unless they served no other draft beer.

Until last year, Coors had withstood all its trials and tribulations without any significant loss of revenue. Then the company suffered a new experience: an actual drop in sales. The chief losses were sustained in Coors’ rich California market, and in Arizona and New Mexico, where sales declined an average of 5 per cent. Was this because of boycotters? Or bad weather? Or bad salesmanship? Or has the Coors mystique finally begun to wear off?

“We’re not exactly sure what happened out there,” says one of Coors’ company spokesmen. “It’s the first time we’ve had a surplus of beer since World War II.” This surplus is what has impelled Coors to embark on its first major territorial expansion program in over a quarter-century: the recent move in Texas.

Coors has actually served parts of Texas since 1948, when it moved into El Paso, and later, portions of West and North Texas. In 1966, the company granted distributorships in the Dallas-Fort Worth markets and as far southwest as Brownwood and Del Rio. Still, company executives used to describe their domain as “ten states plus Texas,” since Coors had distributorships covering only 35 per cent of the total Texas market area. Then, last July, about a month after going public on the stock market, Coors announced it would complete its penetration of the third-best beer-drinking state in the nation.

Exact details of the way Coors decided to pick its new Texas distributors are hard to come by, since the company refuses to provide more than a general account of its procedures. And it appears that different approaches may have been used in different parts of the state. Still, a review of the forms and questionnaires sent out to applicants and interviews with those who succeeded and those who failed provide the following basic scenario:

Coors first sent letters to all those who had made prior written inquiries about the possibility of obtaining a Texas distributorship, and asked them to send a letter reaffirming their interest. The company says it had some 4000 such inquiries on file, many of them over ten years old, and that this first letter-only stage resulted in cutting the number of applicants in half. Next, Coors sent out questionnaires asking for detailed personal background information, and for such financial data as a complete projection of five-year cash flows, the type of financing to be used, the number of investors, and so on. These questionnaires asked that applicants frame their answers in reference to specific distributor areas whose boundaries had been determined by the Coors Company (for example, southwest Houston, northwest San Antonio, etc.). The questionnaires also asked about political and civic involvement, and if the applicant would submit to an attitude survey and a lie-detector test.

Estimates of the time and expense necessary to complete this initial questionnaire range from ten days and a few hundred dollars to a few months and several thousand dollars. One successful applicant said he put in three months of basic research, including one month of concentrated time spent on developing the questionnaire into a unified presentation; out-of-pocket expenses, he estimated, were in the neighborhood of $500. Another successful applicant with prior experience distributing another brand—and distributors of almost every Coors competitor applied for the new distributorships—said the questionnaire was “the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” He and other applicants familiar with various types of franchising operations agreed that the Coors questionnaire was far more exhaustive—and exhausting—than applications for any other type of franchise business.

After this questionnaire stage, the procedures varied from district to district, but a look at how the process was handled in Houston provides some idea of the overall design. According to one successful Houston applicant, each of the questionnaires was studied by two panels of people at the Coors brewery. For the Houston area, this task involved the perusal of some 800 sets of forms and presentations. By this sort of review, the number of Houston applicants was cut to 350, and then to 50. Next, the Coors selection team scheduled personal interviews with these 50 groups in Houston. Some applicants say the Coors people stressed questions about political involvement. Others, particularly the successful ones, say that the interviews essentially repeated and expanded upon the questionnaire.

At any rate, the Coors interviewers then handed out a 9-page, 114-question psychological attitude survey which they asked applicants to complete and return to the brewery. This test was designed to gauge personality motivation, attitudes toward authority, aptitude for leadership and authority, and other psychological traits. Among the yes/no questions answered by Coors applicants were the following:

• “Would you want a position of such high authority that many of your decisions would be certain to hurt some people?”

• “Do you get pleasure from the feel of a good tool in your hands?”

• “Do you feel most people will tend to misrepresent the facts if they have something to gain by doing so?”

• “Do you sometimes feel it necessary to act harshly in order to teach someone a lesson?”

• “Do thoughts about what you ought to be doing keep you from ever relaxing completely?”

Shortly after the personal interviews—too shortly to have had time to process the attitude survey, some applicants say—the Coors Company made another cut, reducing the number of groups still in the running for the six Houston area distributorships to twelve. These twelve groups then flew to Golden for another round of personal interviews at the brewery. A little over a week later, half of the twelve groups were recalled to the brewery and told they had been awarded Coors distributorships for the Houston area.

For some, it would turn out to be the best news since the building of the Manned Space Craft Center. For others, it meant frustration and failure. As the names of the new distributors for Houston and other Texas cities were announced, rejected applicants across the state charged that the whole selection process had been rigged from the beginning. Nowhere were businessmen more incensed than in San Antonio, where Coors interviewed just six out of 800 original applicants. Only one group of San Antonians was eventually selected for the four Alamo City distributorships; the other three went to runners-up from Austin. Coors simply passed over the cream of the Anglo business community, including such locally prominent applicants as former City Councilman Alfred G. Beckmann, former State Senator Nelson Wolff, and former Chamber of Commerce president and television executive Bob Roth.

“Looking back on it, these Coors people may be smarter than they have been given credit for,” one prominent San Antonio businessman remarked cynically. “By getting us to fill out all those forms, they got the benefit of several thousand dollars worth of research and information they otherwise would have had to pay for.”

Even more maddening to some San Antonians was the fact that Coors completely ignored the city’s Mexican-American majority. San Antonio’s one Mexican-American distributor is from Austin. Coors turned down men like Bexar County Commissioner Albert Bustamante, who applied in partnership with the city’s most successful Mexican-American businessman, Frank Zepulveda, known in some quarters as “Mr. West Side.” “I think what they did is an insult to the Mexican-American community,” Bustamante says. “Our group had a man [Zepulveda] who has built up an $18-million-a-year produce business. Just from a public relations standpoint, it would make sense to have selected him. But because Coors ignored the local community, they’re gonna find hostility in the community leadership. This is surfacing more and more. There is already a boycott by LULAC and the GI Forum. I don’t believe in boycotts personally, but I’ll let the organizations who want to do it go ahead. I just can’t understand why Coors did what they did. Why choose an outsider? Why import a Mexican-American? We’ve got quite a few of them right here.”

However, San Antonians were not the only ones to see local citizens passed over in the awarding of distributorships. As it turned out, the majority of men Coors selected were not residents of—and not necessarily applicants for—the areas they were eventually designated to serve. In fact, at least two of the state’s new wholesalers were not even residents of Texas at the time they were selected.

The announcement of the new Coors distributors also prompted charges of racial discrimination based on the fact that only 5 of the 29 groups chosen include men with Spanish surnames and none include blacks. “Obviously, Coors is right-wing, redneck, conservative, and Dixiecrat,” rails black State Representative Mickey Leland of Houston. “They’re racist—it’s as simple as that. A lot of black people applied, but they were obviously not given any real consideration. It should be incumbent upon the black community to boycott the hell out of Coors, but black people will probably drink a greater percentage of Coors than anyone else.” Among the black applicants for Coors distributorships was Dr. Marion Ford, a well-known Houston dentist and entrepreneur who applied with a group including former State District Judge Andrew Jefferson. Dr. Ford stops short of the language used by Leland, but agrees that black applicants apparently did not get fair consideration. “It’s really a problem with Coors,” he says. “I don’t think the government should tell them who to award their franchises to, but, at the same time, there has to be a sense of fair play. Many blacks buy and drink Coors, yet not a single distributorship was awarded to a black. And you had some super-blacks—what I call ‘super-niggers’—applying. This kind of thing is very bad. It perpetuates a certain negativism. Right now, I’m trying to decide how to handle an appeal to the company based on a sense of fair play.”

Is it true, then, that the whole selection process was predetermined from the beginning? As one frustrated applicant puts it, “It looks that way,” but a month-long investigation uncovered only hearsay evidence that a few of the most prominent new Coors distributors may have known early in the game that they had “the inside track.” At the same time, many of those previously rumored or reported to have obtained a Coors franchise (Agnew, Connally, former Governor Allan Shivers, House Speaker Billy Clayton, San Antonio businessman-politico John Monfrey) did not get one. Some people who were close to the Coors family (Alan Shepard, for one) ended up with a distributorship; other long-time friends ended up with nothing. Successful Coors applicants all deny that there was any sort of pre-selection; in fact, nearly all say they can only speculate on the reasons why they in particular were chosen since Coors never explicitly told them. The company itself will make “no comment” on the substantive aspects of the competition, except to say that it chose “the best” of the applicants and that the Coors family had no personal involvement in the selection process.

Still, a look at the list of 29 new Texas distributor groups reveals a number of significant patterns on Coors “quality-control” team. One is the choice of several men with high-level political connections. The company truly had its pick of the crop here, as nearly every name politician in the state had made application. The best known of those Coors finally selected is former Austin Mayor Roy Butler, one of the most powerful businessman-conservatives in the capital city. Coors granted Butler the sole rights to Austin and Travis County, the most sought after of all the Texas distributorships because of its size and large student population.

Less well known but no less well connected is the team of Ralph O’Connor, 49, and Manuel A. Sanchez III, 34, winners of one of the six Houston-area distributorships. By far the richest individual on the Coors team, O’Connor is the son-in-law and business associate of Brown & Root and Texas Eastern co-founder George R. Brown. O’Connor’s partner, Manny Sanchez, is a smooth-talking former regional director of the Department of Housing and Urban Development who was educated at the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton School of Finance. He is also a former high-ranking employee of Wilson Industries, a firm run by another George Brown son-in-law, Wally B. Wilson of Houston. Sanchez, however, says political ties really had little to do with his success; Coors selected O’Connor and him because, as he remarked, “We’re faithful, loyal, kind, obedient, true, and we drink beer.”

Also among the ranks of the politically connected members of the Coors team are William R. Jenkins (Columbus-El Campo), an aide to Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby and nephew of former top LBJ aide Walter Jenkins; Roland R. Nabors (San Antonio), the director of the Tax Records Division of the State Comptroller’s Office; and Austin attorney Charles Crenshaw (Beaumont), a former assistant attorney general who is the father of pro golf star Ben Crenshaw.

Then there are the publicity generators, the celebrities. Should Coors ever decide to market on the moon, they have two distributors who are already familiar with the territory: Alan B. Shepard (Houston), the first American in space and the fifth person to walk on the lunar surface; and Charles M. Duke (San Antonio), the tenth man on the moon. The Coors team also includes a professional football player, former Dallas Cowboy tackle Bob Lilly (Waco), and two baseball players, Bob and Ken Aspromonte (Houston).

Some of Coors’ selections, though not surprising in and of themselves, contradicted Coors own publicly quoted statements about the kind of men they were looking for. Last summer, Bill Coors told a meeting of New York stock market analysts that Coors seeks distributors “with no previous experience in the beer industry,” adding that “an experienced beer distributor would have a difficult time with us.” But, true to its image as “the brewery that breaks all the rules,” Coors awarded 9 of the 29 new Texas distributorships to groups which included men who had prior experience in the beer industry. In fact, at least 6 of the new distributorships went to men who had prior experience with the Coors Company itself. Again, the company had its pick of the crop, as at least one present or former distributor of every other conceivable brand made application. Among the more notable of those selected are Joe Polichino, Sr., and Jr.; the elder Polichino has been distributing beer in Texas since the Repeal of Prohibition and is a former president of the Wholesale Beer Distributors of Texas.

Of the 29 distributorships, then, only 12—or slightly less than half—went to groups of men who could be classified solely as small, independent businessmen with no major beer, political, or celebrity experience. And all of the new distributorships went to conservatives.

Not all of Coors’ more illustrious new distributors have proven themselves to be such outstanding businessmen, however. Take Alan Shepard. In 1969 he was the co-chairman of the board of the First National Bank in Baytown, and, along with two partners, held controlling interest in the bank. By the time Shepard was bought out, the bank had been the subject of considerable adverse speculation in banking circles and had suffered such a blow to its reputation that it changed its name and its charter from national to state. While Shepard cannot be tied directly to any of these problems, his stewardship did not set new records for good management.

Nonetheless, stars like Shepard and the other politically connected members of the Coors team may soon come in handy. In addition to its other battles, Coors expects to be skirmishing in the Texas Legislature. One of its pet bills will probably be legislation to permit sale of its seven-ounce can, or “split”; this smaller container has proven to be highly popular among Coors’ female customers in other states because each can has about half the volume and calories of a twelve-ounce can. Coors is also likely to push for approval of its newly developed plastic container.

Beer industry reaction to Coors’ move in Texas and its new distributorships has been mixed. “We don’t even speak the word of that . . . that company that brews out there in that western state,” storms Pearl beer executive Frank Horlock, who himself once applied for a Coors distributorship. “I’ve been giving them about all the free word-of-mouth advertising I’m gonna give them. People ask me at parties, ‘What do you think about Blank’ and I tell them how great Blank is, and what a nice guy Bill Blank is. Well, I’ve just decided to wise up.”

Those who will talk about Coors seem to be bracing themselves for what Lone Star executive Barry Sullivan predicted would be a marketing “Battle of the Trenches.” “In no case will the retailers be granting any more overall space in their stores to beer,” he explained. “Coors will have to get its space just like any other new brand that is introduced. That’s why it’s important for us to have people in there battling. For example, when Coors opened in Waco with fourteen trucks, we sent fourteen of our men to Waco and visited every account. It only makes good sense to protect what we’ve worked so hard to build.”

Executives of other brands, most notably Schlitz and Budweiser, said this so-called “Battle of the Trenches” is something that goes on every day. Coors, they said, would prompt no special response from them. Some even seem half-glad Coors has finally made its inevitable expansion here. “We’re ready to get it on with anybody,” says Houston Schlitz distributor Hal Hillman. “When Coors gets full distribution, they’ll be just another competitor. And its gonna be more competitive here in Houston than in any other market they’ve been in yet.”

Of course, Houston is the city where Coors has an astronaut, two baseball players (if a former Astro can be considered an asset), a long-time beer industry leader, and a relative of potentate George Brown. In most markets, Coors has done exceptionally well against the same type of brand competition it will face in its new Texas territories. After the initial “give-it-a- try” rush, Coors usually emerges with about 15 per cent of the total market the first year, then enjoys growth rates that eventually reach between 40 and 70 per cent of the market. Executives of other brands are quick to point out that this process took a little longer than usual in Dallas. Coors’ initial market share there was only 11 to 12 per cent, and it took nearly seven years for Coors to attain its present number one standing with 40 per cent. But that time lag is at best small consolation for the competition.

Who will get hurt the worst? Will home brews like Pearl, Lone Star, and tiny Shiner be forced out of business? Or will the majors bear the brunt of the loss? Schlitz, which holds over 40 per cent of the market, and Budweiser, which holds about 20 per cent, currently rank one and two in Texas. They have the most to lose. However, experience in other Coors states has shown that these two national beers remain heavy contenders, continuing to hold onto 20 and 30 per cent of the market. It is the smaller local beers and beers on a downward trend in sales which suffer the most. In Texas, this would likely mean Shiner and Pearl. Lone Star may perform slightly more successfully against Coors because of its current upward trend, and its youth-popular Long Neck bottle. Then again, it is in the youth market that Coors often scores its biggest gains. Of the other national beers, Millers may prove a surprisingly strong challenger. Its new Miller Lite is far and away the fastest-growing beer in the country; in fact, demand has been so great that wholesalers have been hard pressed for months.

While acknowledging the probable success of Coors in Texas, other beer industry sources express serious doubts about the success of certain of the new distributorships. The chief trouble, as they see it, is that Coors granted too many distributorships in large cities like Houston, where there are six (including Conroe), and San Antonio, where there are four. Other brands generally have only two Houston distributors (Schlitz has just one), and only one San Antonio distributor.

Although the Coors Company is characteristically close-lipped about its reasons for dividing territories, one factor it does cite is the enormous initial capital cost. Most of the new metropolitan distributors agree that a good ballpark figure for the total investment necessary is $1.2 to $1.5 million, including at least $300,000—and sometimes more—in cash. There is no franchise fee, since Coors distributorships are by appointment only, but this total investment figure is still considerably more—some say half a million dollars more—than what it would take to launch a distributorship of another brand. The primary cause for these extra costs is Coors’ insistence that warehouses and trucks be kept refrigerated to less than 40 degrees. Nor does the high cost of selling Coors end with capital investment. The need for constant refrigeration means higher costs for maintenance and, of course, utilities. If Coors had divided Houston into just two districts, the cost of the initial investment necessary would have risen to more than $3.5 million for each distributor.

Another reason Coors granted so many new distributorships may derive from the company’s recent sales decline in California. According to an investment analysis by Goldman Sachs, one of the factors behind this unusual decline was a failure of the large Coors distributors there to market aggressively—either because of the size of their territories or because they relied on the seemingly inherent success of the Coors brand. But Coors may have over-corrected. Under FTC rules, Coors distributors are free to cross the boundary lines of their territories, and neither the company nor competing distributors can do anything to stop them. Some optimistic rivals predict that if sales are slow, the new Coors distributors may find themselves in internecine battles to determine the survival of the fittest.

Coors’ largest wholesale outlet in Texas is the exclusive distributorship for Dallas, which was granted back in 1966 to a group led by Raymond Willie. According to Willie, his distributorship currently handles approximately six million cases each year. At a profit of $1 per case—the industry average in Texas—this rather easily translates into a cool yearly profit of $6 million. Still, the beer business is a low-margin business—8 per cent is a large profit by industry standards—and Willie’s huge earnings are directly related to his tremendous volume. None of the new Coors distributors is expected ever to approach the Dallas volume—none of them have anywhere near as large a territory. On the other hand, if each of them does only one-sixth as well—and this depends as much on the overall success of the brand as well as on their marketing skills—they will eventually become millionaires. Because of the size of the initial investment and the fickle nature of the beer market, it will probably take at least three years to tell whether Coors will prove to be a guaranteed bonanza for all 29 distributors.

Should a Coors distributor not do well, he may find himself faced with a largely unanticipated problem: how to sell out. Coors distributors are allowed to sell their businesses for whatever they can get. The hitch is that Coors must approve the buyer. Coors’ former Del Rio distributor, D. R. Dixon, is currently suing Coors, claiming that Coors refused to let him freely negotiate the sale of his distributorship. Dixon’s attorney says the distributor had a group of buyers who agreed to pay $300,000 for the Del Rio outlet; then the buyers went to Golden, talked to Coors, and returned to say they would pay only $200,000. After the papers were signed, the group paid only $100,000. Coors, as usual, will not comment.

Should one of the new Coors distributors get stuck with a losing business, he may well find himself with no viable means of support. Most, though not quite all, have resigned from their previous jobs and divested themselves of other franchises and time-consuming business interests. In general, Coors requires that the beer business be their distributors’ primary occupation—something Coors no doubt feels will enhance “quality control.” Roy Butler, for example, has had to sell his lucrative Lincoln-Mercury car dealership.

Not too surprising, however, Coors new Texas distributors voice absolutely no qualms about what they got and how they will do. They are, to a man, elated over their appointments. “I wouldn’t exactly call it a money machine,” says one. “I’d call it an opportunity machine. But if I work hard, I will make money.”

The only voices left to be heard are those of Texas consumers, and their most significant comments will be made at the cash register. Coors is already available at new outlets in Waco, Palestine, and Longview. Roy Butler’s Austin Coors is scheduled to open on April 1. The San Antonio and Houston distributors have set May 1 and May 15 as their target dates. The rest of the new outlets should be in operation by midsummer. Most expect to price their beer about the same as Schlitz and Budweiser or perhaps a little higher. They must, after all, maintain quality control.