This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Who’d have thunk it? Texas, bastion of cowboys and crude oil, has become the fifth-largest wine-producing state in the nation. In 1975 Texas had a mere 2 wineries; now it boasts 28, scattered from the High Plains to the Hill Country, from the Mexican border to the Louisiana state line. That a land so thoroughly imbued with the wild and rugged ethic of the West could embrace such a symbol of refinement and taste as winemaking is an intoxicating irony—but that very irony is a large part of the success of the state’s most unlikely industry.

Since the mid-eighties, the Texas Department of Agriculture has aggressively promoted viticulture, even declaring in one press release that “an old-fashioned Texas backyard barbecue is not complete without a bottle of Texas wine.” Other boosters include George and Barbara Bush, who served the wines of their adopted state to the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev and Queen Elizabeth II. Less-visible celebrities, in the guise of restaurateurs and chefs, do their bit by sponsoring wine competitions and festivals all over the state. But the two main sources of support are the mystique of the name “Texas”—which attracts repeat buyers, from loyal natives to Western-happy Japanese—and the impressive qualities of the wines themselves.

Historically, Texas has long had winemaking ties. In 1662 missionaries brought grapevine cuttings here from Mexico, and a century later the first vineyards were thriving. By 1819, one map noted, near the El Paso area, “excellent wines made here.” German immigrants arriving in Central Texas throughout the nineteenth century further bolstered the industry. During Prohibition, Texas wine production dwindled, and it remained inconsequential until agricultural experiments in the mid-seventies revealed the affinity of Texas soil and viniferous grapes.

In 1991 the wine industry poured $97 million into the state’s economy, a figure that represents tons of grapes harvested, number of jobs provided, total sales of finished wines, and even the industry’s secondary but significant role as tourist attraction. While few Texans would choose to tour a slaughterhouse or a cannery, the cachet of viticulture lures hundreds of thousands yearly. No agency keeps statewide figures, but Messina Hof in modest-sized Bryan attracts 50,000 visitors alone, and 20 percent of Hill Country wineries’ sales come from tasting-room purchases.

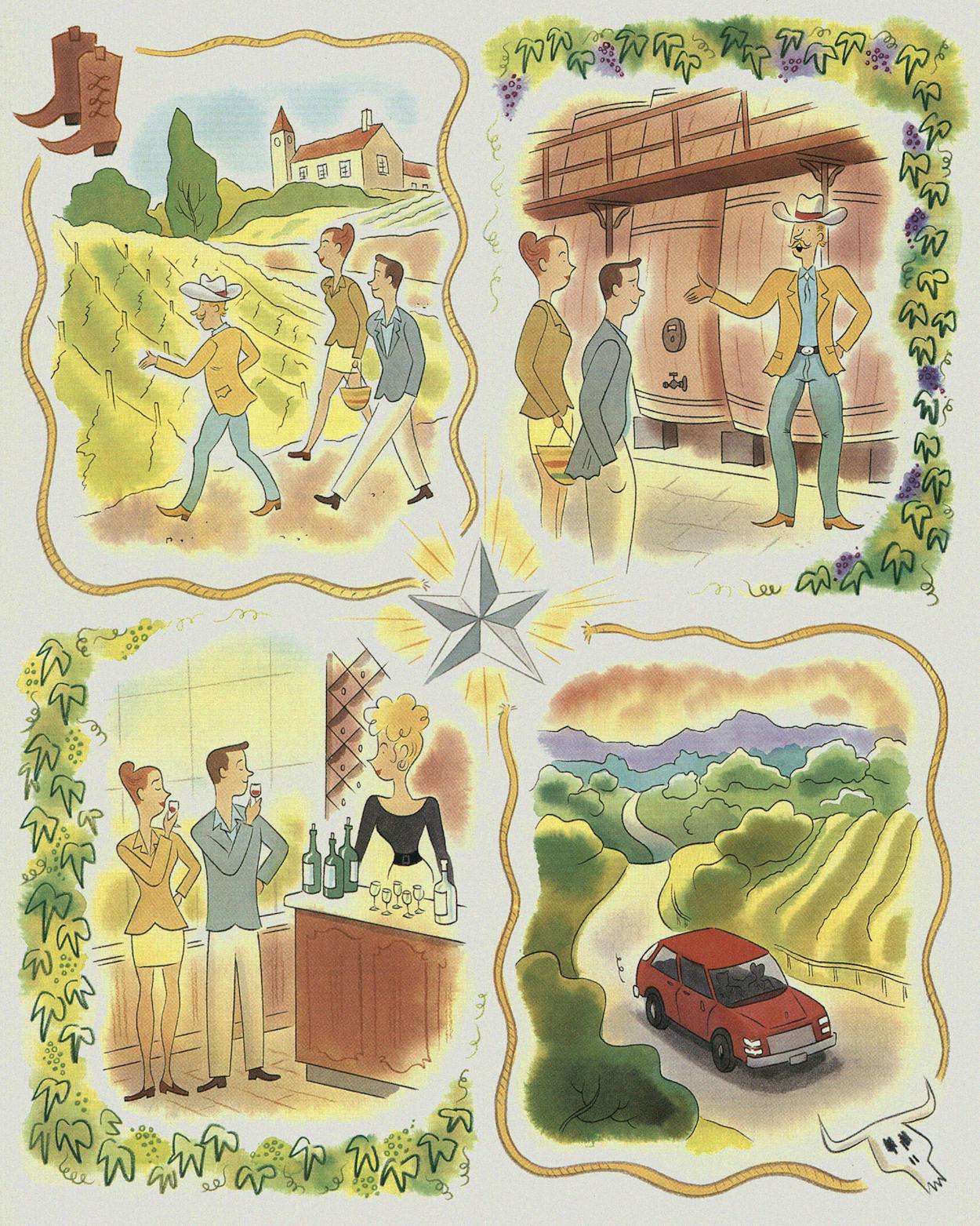

Still, unless you are a confirmed oenophile, a trip to one or two wineries is plenty. I know; I visited ten. Diverse as the physical settings may be, and as much as the wines vary, the day-to-day (or rather, season-to-season) workings of a winery remain much the same anywhere. Late July and August are the best times to plan a trip, since the ongoing grape harvest keeps the machinery humming. Some partisans favor spring—especially in the Hill Country, which offers the added charm of wildflower viewing—but, except for grafting in the early fall, the industry is essentially dormant for the rest of the year. Regardless of when you visit, though, make sure the winery is open; most offer tours only on weekends.

A winery tour is essentially a short course in winemaking. You’ll learn an assortment of vini-facts, largely centering on the differences between reds and whites in both taste and production. Guides range from young matrons in pearls to good ol’ boys in gimme caps. Wineries with vineyards attached are more fun; you can visit your future beverage in its infancy. Inside, expect to see a welter of medals and awards on display, curious machinery such as the stainless-steel press (reminiscent of the Spanish Inquisition), and giant fermentation and storage vats, often thinly coated with ice. The rooms are chilly, which I found refreshing in hot weather, but if you are cold-natured, bring a sweater. Tours close with a tasting, generally of two whites and a red—a breakdown that reflects Texans’ overall preferences in vino (we red-wine fanciers need a lobby). If you are young, or young-looking, expect to show an I.D. And don’t worry about your ability to drive home; you’ll likely sample less than a full glass altogether. At nearly all Texas wineries, you can acquire a few bottles for your home cellar as well as various vinicultural souvenirs—and a changing opinion of Texas culture.

Below, my favorite quartet of Texas wineries, plus six more especially worthy of a visit.

Messina Hof

Four miles east of the intersection of Texas highways 6 and 21, Bryan; 409-778-9463 or 800-736-9463. Paul and Merrill Bonarrigo’s Messina Hof, named for their ancestral hometowns (in Sicily and Germany, respectively), combines a pretty setting, bright workers, and a tasteful gift shop. Originally quartered in a mobile home surrounded by corrugated-steel shacks, Messina Hof now occupies a 1901 Ursuline girls’ school, which the Bonarrigos dismantled, moved, and reassembled on their property. The winery’s annual yield has similarly expanded, from 5,000 gallons in 1983 to an estimated 75,000 gallons this year.

Our personable guide first walked us into the vineyards—43 adjacent acres dotted, fittingly, with wine-cups—to show us the then-tiny grapes and then urged us to return in late July or early August, when the public is invited to help harvest the mature fruit and to participate in its annual grape stomp (call first to confirm dates). Besides offering a straightforward explanation of the making of reds and whites, our guide finished our tour with a thorough minicourse in wine tasting (sparkling grape juice was provided for minors). She explained, among other things, how to read a wine label and how to “slurp and cluck”—as she put it—to enhance the taste and smell of any vintage. (After sampling a dry white, she joked, “Was it good for you too?”) She encouraged tourists to ask questions, assuring us that no query could be sillier than her all-time favorite: “Does that year on the label mean the date the wine expired?” An A&M alum, she proudly showed off Messina Hof’s Aggie Tradition label, which depicts a generic Reveille next to a pair of corps boots.

After the tour, visitors are welcome to linger on the winery’s sunny decks or picnic by its small lake. The resident deli offers fresh breads, patés, cheeses, and chocolates. (Try the venison paté and the truffles made with Messina Hof’s port, which, our guide assured us, is also great over Blue Bell Homemade Vanilla.) Surprise gifts for the folks at home might include grape-cluster salt and pepper shakers, a grapevine-patterned afghan, and a selection from the staggering array of grape-theme jewelry.

Ste. Genevieve

Twenty-seven miles east of Fort Stockton, off Interstate 10 east; 913-393-2417. Ste. Genevieve’s television commercials tout it as “all that is Texas,” when in fact it is half that is France. Texas’ biggest winery, in terms of both acres planted (1,016) and gallons sold (697,000 in 1992), Ste. Genevieve occupies land owned by the University of Texas Land Systems and leased to Domaine Cordier U.S.A., an American offshoot of an established French firm that also operates half a dozen wineries back home. This intercultural combination of expanses and expertise enables Ste. Genevieve to produce wines that are tasty but inexpensive; most Texas wineries are too small to price their products as cheaply as Domaine Cordier does. (The company expects to sell 160,000 gallons of Sauvignon Blanc this year in France alone.)

For $8, visitors can hop Fort Stockton’s Roadrunner Bus for the half-hour drive to the vineyards, a huge if undistinguished compound familiar to regular travelers along Interstate 10. Startling a white-tailed deer, we bucketed over the rutty field roads and disembarked for a quick lesson in grape varieties; our cheerful middle-aged guide informed us that since Texans declined to buy French Colombard, the winery has now phased out that variety in favor of the nonvintage Texas Chardonnays its customers prefer. She discussed pruning and grafting, pointing out that Ste. Genevieve imported experienced French workers for its first few years until locals became skilled enough to take over. Because Ste. Genevieve grows grapes so close to the winery, the fruit can be pressed within thirty minutes of being picked. An elaborate drip-irrigation system fueled by eleven irrigation wells provides appropriate moisture—though a sign warns, “Do Not Drink the Water.”

Tours close with a tasting, generally of two whites and a red—a breakdown that reflects Texans’ preferences.

Inside, the winery is a study in opposites: concrete-floored, windowless hangars dominated by massive, blinking control panels that are worthy of the starship Enterprise. Reading the labels on various vats and presses—“matériel d’embouteillage,” “certificat de jaugeage”—offers a chance to revive your college French, yet because the seasonal workers here are largely Hispanic, some signs are trilingual: “Women/Damas/Femmes.” A framed poster pays homage to the winery’s namesake, a fifth-century nun who became the patroness of Paris.

Ste. Genevieve has no gift shop; to its corporate staff, the operation is strictly business. (“He’s French,” our guide said of the winery’s director. “He doesn’t think like us Texans.”) With no corkscrews, T-shirts, or similar goodies, the closest thing to a souvenir is a dead vinegarroon in the parking lot. Yet the wine flows freely—another Gallic-inspired difference. Our group of twelve finished six bottles, then reeled to the waiting bus, thankful not to be at the wheel.

Fall Creek Vineyards

Two and two tenths miles northeast of the post office, on FM 2241, Tow; 312-476-4477. Although the High Plains are generally acknowledged to have the most ideal growing conditions for viniferous grapes, the Hill Country is Texas’ wine stronghold, with ten thriving operations. The oldest and largest, and arguably the prettiest, is Fall Creek Vineyards, on the northern edge of Lake Buchanan in scenic Llano County. Genteel Fall Creek feels like a transplanted slice of the French countryside. Owners Ed and Susan Auler, recognizing the area’s similarity to several wine-wise regions of France, first planted grapes on their cattle ranch in 1975. Today 65 acres of healthy vines flourish atop root stock from a hardy Central Texas variety called Champanel, which was first developed by an unsung agricultural whiz, Thomas V. Munson of Denison. A century ago Munson exported the sturdy roots to France, where their arrival bolstered that country’s ailing vineyards; today the Aulers habitually graft preferred varietals such as Chardonnay onto a new generation of Champanel roots. They raise a total of eighteen types of grapes, including the relatively uncommon Sémillon.

This agricultural slant affects Fall Creek’s entire operation. Though tours are somewhat perfunctory, our elderly, slow-talking guide emphasized the arability of the land and reeled off statistics: grapes should be picked when their sugar content is 22 percent or so; plant diseases such as cotton-root rot, mildew, and fungus kill grapes “like toxidiosis kills chickens.” Inside the tank fermentation room, a pungent and yeasty odor lingered. (“Pee-yew!” exclaimed a pint-size tourist, while the adults breathed in deeply.) The adjacent barrel room was chapellike, down to the cool darkness and the stained-glass window showing laden grapevines; the heavy oak door came from a stable of the nineteenth-century Louis Pasteur Hospital in Paris, and a plaque engraved with a Pasteur quote adorns its wood: “Wine can be considered, with good reason, one of the most healthful and the most hygienic of beverages.”

At the end of the tour, our guide turned us over to the chatty tasting-room staff. We sipped three whites and two reds and then a blush—“an all-purpose wine,” one pourer explained. Engaging in stereotypical (that is, slightly hokey) vino lingo, the same staffer offered a thumbnail personality profile of each wine: One was “floral, a bit grassy,” another “not too tart or oaky.” She also recommended specific pairings of vintages with victuals, such as Fall Creek’s Chenin Blanc with crabmeat Alfredo. Another energetic employee urged us to return on August 14, 21, or 28 for Fall Creek’s annual grape stomp, which includes chamber music, hayrides, and a cork toss for kids.

Llano Estacado

Three miles east of the intersection of U.S. 87 and FM 1785, Lubbock; 806-745-2258. The High Plains’s preeminent winery sprang from an agricultural experiment by two Texas Tech professors in 1976. Today it exports wine to 28 states and 5 European countries; a framed certificate in its spacious wood-floored tasting room attests that its Chardonnay was the first Texas wine sold in Russia.

Our tour guide, a Tech senior, was full of good humor and useful information. She congratulated a member of our group for correctly pronouncing “Gewürztraminer,” a German grape, and she was the only person at any winery who mentioned the threat of Phylloxera, a tiny licelike insect that has devastated French and California vineyards and that vintners fear might migrate to Texas. She explained the color-coded bottle system (dark green for reds, clear for whites and blushes) and the different tastes created by the complex procedure of flame-treating the inside of oak barrels (the French and the American methods differ considerably). Recognizing that preferences differ, Llano Estacado offers tasters a “yuck bucket” to dispose of a wine they don’t like; many wineries expect you to drink up. A gift shop in the tasting room offers such specialties as Cabernet Sauvignon raspberry fudge sauce and can provide personalized labels for weddings, gifts, and more. Feeling bountiful? Pop for the $275 five-liter bottle of Cabernet.

Bell Mountain/Oberhellmann Vineyards

Fourteen miles north of Fredericksburg, off Texas Highway 16; 210-685-3297. It pays to call ahead; a vineyard employee, asking where I was coming from, suggested a route via FM 1323: “It’s a real pretty drive.” She was right, and Bell Mountain Vineyards was a fitting finale, with oceans of verdant vineyards, picnic tables in a copse of live oaks, and a sprawling châteaulike house (or perhaps I should say Schloss-like, since the owners and the region are very Germanic). All vintages are estate label—that is, made on the premises solely from the produce of the winery’s own vineyards, 55 acres strong.

Bieganowski Cellars

5923 Gateway West, exit Trowbridge Drive north, El Paso; 915-775-0842. Bieganowski is named for its owner, a psychologist/neurologist/acupuncturist whose office is next door. Whenever there’s time, a mini tour is available from an employee—likely the winemaker himself, Ken Stark, a former farmer-rancher from Hereford. The winery has a pleasant tasting room, with original art and wine-stained floors—meaning the wood is stained a burgundy color, not that visitors were careless. Close to the airport, Bieganowski is a convenient stop for a last-minute hostess gift.

Cap-Rock Winery

Just east of U.S. 87, at Woodrow Road, Lubbock; 806-863-2704 or 800-546-9463. Cap-Rock is housed in an attractive mission-style building with vine-entwined trellises and pergola outside and grape-patterned sofas and a grape-hoisting Caddo Indian statue inside. Our tour guide, a Tech student, was admirably enthusiastic; he referred to the press as the “robo-stomper” and imparted some fascinating nuggets of information, such as the fact that corks must be imported from Portugal and cost a startling 19 cents each. Cap-Rock’s label, which sports an expressionist mesa in sunset colors, is a contender for the most Texan design.

Hill Country Cellars

Eight tenths of a mile north of the intersection of U.S. 183 and FM 1431, Cedar Park; 512-259-2092. Twenty minutes from Austin, Hill Country prides itself on its historic limestone building, its unexpectedly bucolic setting (just off a busy highway), and its immense two-hundred-year-old native grapevine. As I drove up, a busy gardener dropped his edger, followed me inside, disappeared behind the counter, and reappeared with clean hands and shirt as the wine steward. Another employee was enjoying a glass of Hill Country’s Chardonnay with his Whataburger at the winery’s picnic tables overlooking its fledgling vineyards, which are expected to yield usable fruit in one to three years for the winery’s first estate labels.

Moyer Champagne

Suite 209B, 3939 Interstate 35 south, in the VF Factory Outlet Mall, San Marcos; 210-396-1600 or 800-328-2259. Here is a winery of a different flavor. Visitors will learn about the méthode Champenoise, by which the bubbly is fermented in the bottle; every day for at least eighteen months workers carefully administer a quarter turn to each of Moyer’s thousands of bottles. Like Ste. Genevieve, Moyer has a strong French connection—in the form of its owner, Henri Bernabé. He imports cases from his family’s vineyards back home, so you can buy a real Beaujolais or Burgundy if you prefer your wine genuinely Gallic (the former was touted as “a great pizza wine”). You can also acquire champagne peach vinaigrette or even champagne soap.

Val Verde Winery

100 Qualia Drive, Del Rio; 210-775-9714. The oldest winery in Texas, Val Verde was built around a nineteenth-century adobe structure in what is now a lovely residential area. It opened in 1883 and survived Prohibition by switching to table-grape production and wine for medicinal uses. “I imagine the local doctors filled quite a few prescriptions back then,” said owner Thomas Qualia, whose grandfather, a native of Italy, founded the business. Val Verde specializes in sweet and potent Tawny Port, which is fortified with grape brandy. For one 23-year period Val Verde was Texas’ only winery. “Used to be I’d call up California wineries asking for some technical advice,” recalled Qualia, “and they’d say, ‘Who? Where?’ or never call me back at all. Now those same wineries send people down all the time to try and sell us services or supplies or whatever. Things have changed.”

- More About:

- Libations

- Wine

- TM Classics