Mexican food brims with delicacies. A few examples are cow’s eye, chapulines (roasted grasshoppers), and escamoles (ant larvae). Too often these are dismissed as “exotic” or as “novelties” by those, including food writers, who aren’t familiar with the components. This does nothing but marginalize traditional ingredients and further reinforce stereotypes, making it difficult for restaurants, importers, and diners to increase their knowledge, expand their palates, and perhaps gain a new favorite snack (chapulines tossed in a bag with Valentina hot sauce are a delightful, crunchy treat). One of these underappreciated, misunderstood delicacies of Mexico is huitlacoche.

As Regino Rojas, owner of Dallas’s Revolver Taco Lounge and La Resistencia puts it, huitlacoche is a treasure. “You should consider yourself lucky to have found some,” he says. “Get it on the spot. Don’t even ask for the price, just get it.”

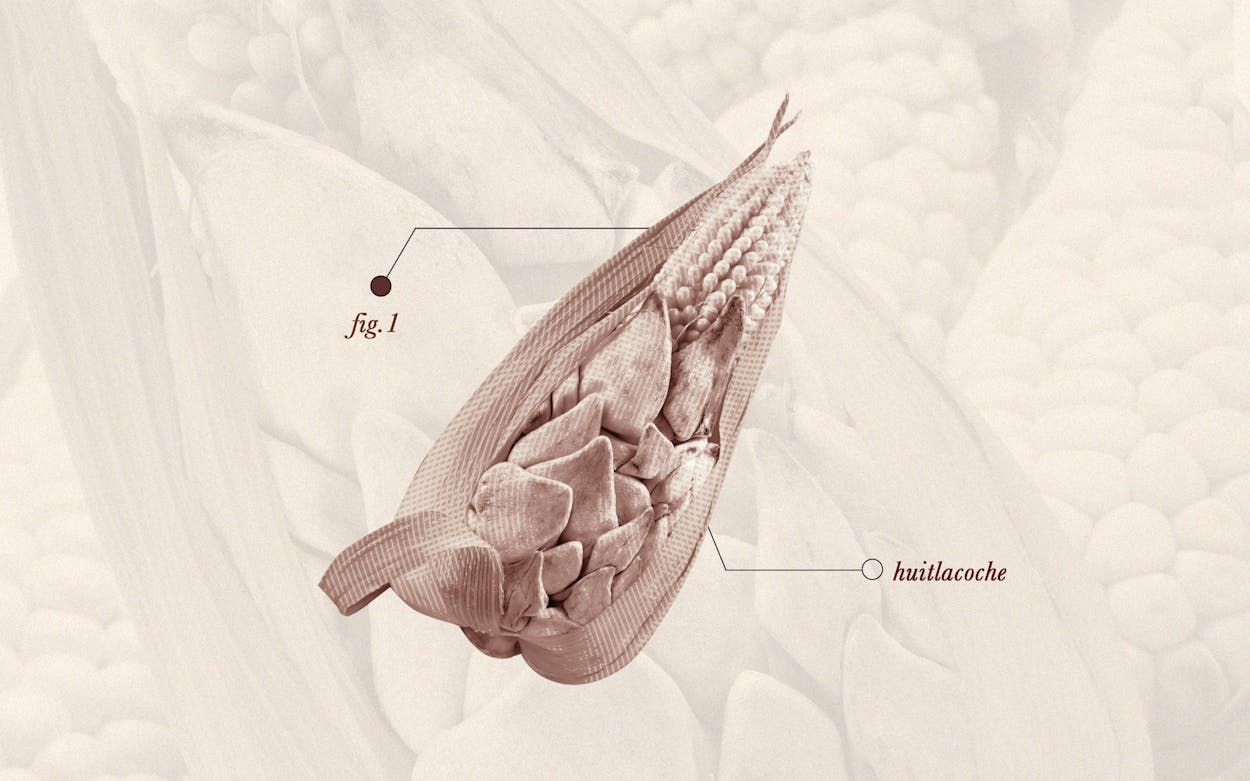

Huitlacoche is a parasitic fungus that blooms from and engulfs kernels of planted corn. But in Mexican cuisine, the fungus (also called cuitlacoche) isn’t considered a nuisance that ruins crops. Instead, huitlacoche is a prized edible delight. Its price on the market—about $15 to $20 per pound—reflects huitlacoche’s culinary status. (You can buy it canned for cheaper, but you shouldn’t: that version is slimy and flavorless.) “It’s black gold,” says José Leyva, owner of Houston-based importer Agropa LLC, a purveyor popular among Texas’s finest Mexican restaurants and chefs. A native of the state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, Leyva gets his huitlacoche weekly from a single family in the town of San Martín Tilcajete, also in Oaxaca.

Leyva recommends clients order only enough for a week. “If you keep it longer, it’s not the same. You can freeze it, but the taste is different.” Although commonly available year round, the ingredient is in season during the rainy months ranging roughly from July to September. “It’s just like wild mushrooms popping up after several days of rain,” says Agropa client Juan Rodriguez, owner and chef of Magdalena’s catering and supper club in Fort Worth.

In the United States, farmers used to view huitlacoche as a threat to be eradicated—an attitude conveyed by pejorative nicknames like “corn smut” or “devil’s corn.” The USDA has studied ways to eliminate “corn smut disease.” More recently, however, U.S. growers have started collaborating with chefs and recognizing the economic and culinary potential of the fungus. A 2016 study led by University of Texas–Rio Grande Valley researcher Alexis Racelis explored the feasibility of cultivating the crop in Texas. “Huitlacoche is potentially a highly profitable crop,” the researchers concluded. If the economic possibility and smoky, nutty flavor aren’t enough for you, huitlacoche is healthy, too—it’s rich in protein, fiber, and lysine, an essential amino acid. Indigenous people in Mexico and Central America figured this out long ago, of course; huitlacoche has been consumed in some cultures for thousands of years, and its name comes from the Nahuatl language, which is spoken today by nearly 2 million people.

Huitlacoche is bulbous or tumorous in shape. When fresh, it is white to silver in color; over time it darkens into shades of blue and eventually into a shimmering ebony when ripe. Like fresh mushrooms, it has a slight earthy smell and a sour, woodsy flavor that evokes truffles when cooked. Huitlacoche is not consumed raw. “If it’s too soft, mushy, and has a strong smell, it has been bruised or it has been too long since harvested,” says chef Iliana de la Vega, co-owner of El Naranjo, a Oaxacan restaurant in Austin. She uses the product for El Naranjo’s empanadas de huitlacoche: golden brown and flaky fried corn masa turnovers stuffed with stewed huitlacoche and cheese and served with a ground tomato-serrano salsa.

But there are myriad dishes in which huitlacoche is used. Perhaps the most ubiquitous is a quesadilla with stretchy, milky quesillo (a.k.a. queso Oaxaca) that bubbles and melts into a rich truss. Huitlacoche is equally delectable cooked in a medley of onion, chiles, and tomatoes with a side of corn tortillas. “You can also use it in soups, or make sauces,” adds de la Vega, another Agropa customer.

Huitlacoche remains relatively rare on Texas menus, but creative chefs across the state have had success with it. Gabe Erales, executive chef of Comedor, serves it in a quesadilla mixed with Texas mushrooms. The dish is one of the restaurant’s top three sellers. “It is something that is an eye-opener for guests who are typically nervous to venture out with new flavors and products from Mexico,” he says.

Hugo Ortega also likes to experiment with huitlacoche, using it in desserts from time to time. The co-owner and executive chef of H-Town Restaurant Group, which includes Oaxacan-inspired modernist Xochi in downtown Houston and Hugo’s in the city’s Montrose neighborhood, was Agropa’s first customer. He describes huitlacoche in a reverent tone that mirrors Leyva’s black-gold remark: “When it’s fresh, it’s like white truffle.”

- More About:

- Tex-Mexplainer

- Tacos

- Mexican Food

- Houston

- Fort Worth

- Dallas

- Austin