Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla ignited the Mexican War of Independence with his Grito de Dolores on September 16, 1810. The priest’s impassioned speech on that date, which we now know as Mexican Independence Day, called for the Spanish colony’s self-determination and freedom. Hidalgo didn’t live to see the end of the conflict in 1821. But General Agustín de Iturbide, who initially fought for Spain before aligning himself with revolutionary forces later in the war, did live to see a free Mexico and was later crowned the first ruler of the sovereign nation.

His reign was short. General Antonio López de Santa Anna (yes, that Santa Anna) broke with his former military superior and declared the country a republic. The conflict that followed led to Iturbide’s abdication and exile ten months later. But first, Iturbide performed at least two notable acts. The first was signing the land grant for Stephen F. Austin’s American colony in modern-day Texas. The second—and for our purposes, the most important—was feasting on chile en nogada during a visit to a nunnery in the east-central Mexican city of Puebla.

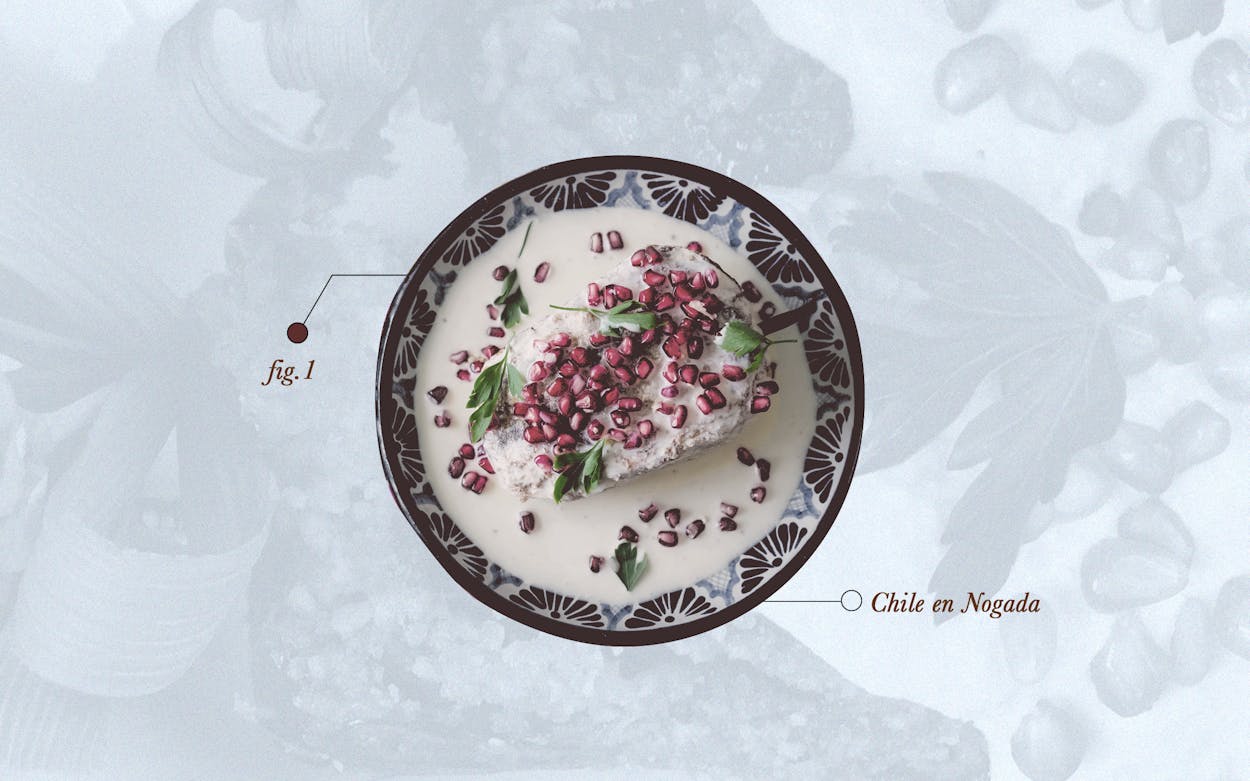

The meal, among the finest of Mexico’s iconic dishes, is traditionally a chile poblano stuffed with a picadillo of beef, pork, and finely chopped vegetables and fruits. Then it’s bathed in a white walnut sauce (nogada) and garnished with parsley and pomegranate seeds. Its colors are those of the Mexican flag. While chile en nogada is available from August to early October, it’s most commonly consumed during the weeks surrounding Mexican Independence Day. That’s especially true in Puebla, where the dish is said to have been created.

Like most origin myths, this one is short, sweet, and probably not entirely true. In 1821, soon after signing the Treaty of Córdoba, which ended Spanish colonial rule, Iturbide visited the Convent of Santa Mónica in Puebla, home to nuns of the Order of Augustinian Recollects. To honor the war hero, whose appearance coincided with the August 28 feast day of Saint Augustine, the sisters feted Iturbide with a banquet—most of whose dishes he refused to eat, since he feared being poisoned by his political enemies. There was one dish, however, that he couldn’t resist. According to a creation story offered by Ricardo Muñoz Zurita in his definitive tome on Mexican cuisine, Diccionario Enciclopedico de la Gastronomia Mexicana, among the preparations was an edible tribute to the new flag’s colors. Entranced by the velvety mixture of sweet and savory notes, Iturbide couldn’t help himself. He cleaned his plate, and thus, the story goes, the patriotic dish was born.

Dig a little deeper, though, and it seems likely that chile en nogada has been around much longer. “Even though I love the nun story, I know it is not true,” says Iliana de la Vega, executive chef and co-owner of El Naranjo in Austin. “Many stories said that [the dish] was created for the independence treaty in 1821, but it seems that there is an earlier recipe from a family cookbook,” she continues, referring to recipes dating back to the eighteenth century. Muñoz Zurita mentions the existence of those recipes in his 2010 book, Los Chiles Rellenos en México, including a version by the Traslosheros family.

Regardless of when the dish originated, one thing is for sure: cooking and eating it in season is key. The patriotic month of September, also called el mes de la patria (the month of our country) in Mexico, is when walnuts ripen. “They need to be fresh, as the thin brown skin needs to be removed to create a white sauce,” de la Vega explains.

Recipes for chile en nogada vary. Some call for the battering and frying of the chiles. But at El Naranjo, the poblano is unfried and is filled with a picadillo mixture that blends more than a dozen flavors: pork and beef, tomatoes, onion, garlic, almonds, raisins, peaches, pears, apples, plantains, pink pine nuts, olives, parsley, and a very important ingredient: acitrón, or candied cactus made from the endangered bulbous biznaga succulent. The nogada sauce is made with peeled walnuts, goat’s milk queso fresco, and milk. The one commonality among all versions of the recipe is a white walnut sauce.

Hugo Ortega, executive chef and co-owner of multiple Houston Mexican restaurants, including Hugo’s and high-end, modernist Xochi, grew up on the border between the states of Puebla and Oaxaca. He believes that the nuns created the dish from the abundance of foods around them, all of them in season, and with a lot of tinkering. For Ortega, working with what you’ve got is just what a good cook does. “It’s so important as a local cook to look at what is around you,” he says. “The nuns went wild creating these beautiful recipes [like chile en nogada].”

For Ortega, it’s a deeply personal dish, not just because he’s Mexican and not just because the dish is a symbol of national pride and Mexican heritage. For him, chile en nogada also evokes childhood memories of traveling through Puebla and seeing children peel walnuts in small bags filled with milk for a little money or candy. Ortega and his staff soak walnuts in hot milk, peel them individually, and then freeze them. The time-consuming process begins in June or July, just ahead of the season for the ingredients. “It takes hard work to understand the dish,” Ortega explains. By the time chile en nogada goes on the menu at his restaurants in September, dozens of people have collectively put in hundreds of hours of work to make it possible.

As with all celebratory dishes, the preparation time is long (at Ortega’s businesses, cooking the dish takes a full day), involves a large group of people, and has rules that extend to proper serving. Regarding the latter, there are two camps: whether the dish is plated tableside or not. Chile en nogada is served at room temperature. “It is very important or the sauce will break,” says de la Vega, who does not believe the chile should be plated in front of the diner. “Let’s be clear on this: the chile en nogada is a dish that was and is prepared and served for the family. Traditionally, the family gets together and prepares the dish. This may take six hours or more to clean the walnuts, and then they feast on it.”

The effort is worth it, says Francisco de la Torre, consul general at the Mexican Consulate in Dallas. The foreign service member reiterates what de la Vega says about family. “I remember helping my grandmother Angelinita in the September preparation of chile en nogada,” he says. “[It’s] a dish to share with the family, with friends in a large celebrating table with tequila, and at the same time a dish to share with the world.”

Want to take on the challenge and make your own? Texas Monthly’s version of the recipe (first published in 2016) is a streamlined version pared down for home cooks, but it still has ample flavor.

- More About:

- Tex-Mexplainer

- Tacos

- Recipes

- Houston

- Austin