When Maurice Mikeska received a call asking if he could prepare enough barbeque for 18,000 at a Labor Day picnic near Bay City, he didn’t hesitate before answering yes. He wasn’t worried that the largest function he had ever catered was for less than half that number in Corpus Christi a few years back. He knew that he could handle the order by simply picking up the telephone, dialing a few numbers in small Texas towns, and enlisting the aid of his five brothers—barbecue specialists every one.

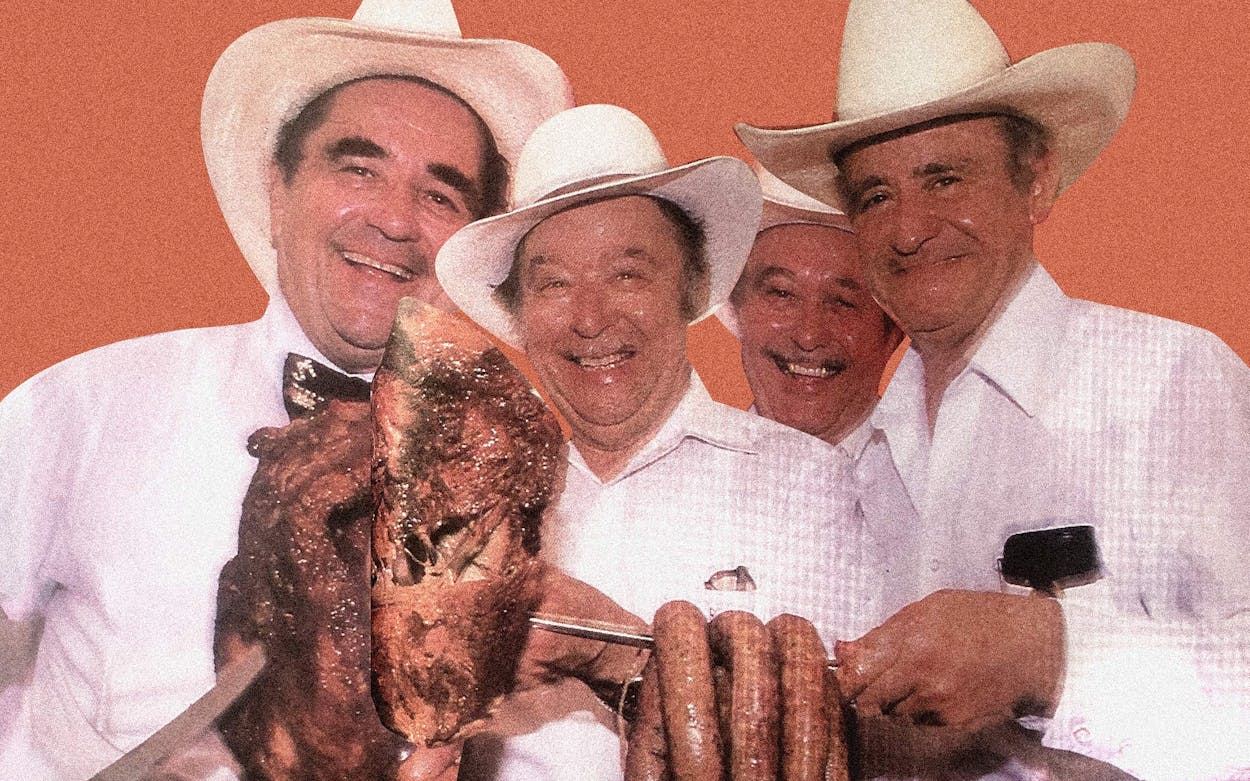

In Central Texas, where the subject of cooking meat over fire arouses as much passion as football, sex, or politics does, the Mikeskas are the first family of barbecue, with more than 150 years of professional experience under their sizable belts. The brothers range in age from 57 to 70, and four of them currently operate restaurants and catering businesses under the family name. Rudy runs one that looks like a large red barn in Taylor, a community of 10,000 that is often cited for having the best barbecue establishments in the world. Jerry works out of a tidy storefront in downtown Columbus, and Maurice’s restaurant sprawls across three buildings in the heart of El Campo. Clem, the baby of the bunch, operates his eater off I-35 in Temple. The oldest brothers, Mike and Louis, who barbecued in Smithville and Temple, respectively, are retired.

Each brother runs his business independently, employing his own philosophy about meats, seasonings, sauces, and trimmings. But this Czech clan shares a family credo of sorts: Get the finest-quality meats (the beef is usually from Colorado, the pork from San Antonio), and make your trimmings from scratch. Take your time (“You might as well throw your watch away in this business,” Clem advises”), and enjoy the meats of your labors—to a man, the Mikeskas eat barbecue daily. Finally, maintain a little family pride. “Now we’re humble about this,” Clem contends. “We may not be the best, but we’re so close to being the best that is makes whoever is the best real nervous.”

When asked why they have dedicated their lives to stoking the pits, each brother will testify, “Daddy was a meat man.” The late John Mikeska taught his six boys (there were also three daughters) his meat-cutting skills. A farmer who worked a small plot of land near Taylor, Mikeska Senior organized what was known as a meat club, a cooperative in which several families would share a cow by splitting the various cuts of meat. Whenever he had butchering to do, he took his youngsters along to show them how it was done.

A task born of necessity eventually turned into a thriving business for Mikeska’s offspring. After World War II the brothers used their butchering experience to get meat-market or food-service jobs, first around Taylor and later in other towns. “Fooling with meat was better than working in the cotton patch,” Jerry says. Within a two-year period each brother owned a meat market only a few hours from home. “We felt that one city was not big enough for all of us,” explains Clem.

The Mikeskas began the barbecue business as a sideline. Before the unsold meat spoiled, they cooked it in pits behind their stores. Less-than-choice cuts were ground into sausage. The brothers started developing a barbecue clientele by word of mouth, and soon their cooking talents became as well known as their carving abilities. Before long, they were serving up meals at weddings and other social functions. In the mid-fifties, when supermarkets and self-service meat counters threatened the butcher business, the Mikeska brothers made a shrewd decision: they abandoned the raw-meat business in favor of barbecue restaurants and catering. As always, they worked together, with Rudy and Maurice passing on tips they had picked up while working in the Army’s food services.

Through it all, the men—who could pass for cowboy matinee idols or Dennis the Menace’s neighbor Mr. Wilson—have shared an unanswering loyalty to each other. They meet frequently at the Bastrop home of their 92-year-old mother, Francis, to talk family and talk shop, and they converse daily on the telephone. “When we get together, we pool our resources,” says Clem. “It’s strictly business. ‘Where do you buy your pork this week?’ Or maybe someone’s sauce needs spicing. Every time my brothers come in, the first thing they say is, ‘Let’s eat.’”

The most obvious tipoff that the Mikeskas are related are the hand-painted-wooden signs, commissioned by Maurice, which are prominently displayed in their eateries and which list all the Mikeska’s Barbecue locations. Cafeteria-style serving lines are standard, as are the mounted wild-game and fish trophies that decorate the walls of each dining area. The meats are cooked in the gas-fired rotisserie pits; the gas is a necessary evil for uniformly cooking copious amounts of meats, Rudy says. (Maurice also uses the original 55-year-old brick pit that he started his business with.

Mikeska’s barbecue is no prefab chain operation. Subtle differences abound. No brother publicly criticizes another, though after some prodding, each will admit to a slight competitive edge over the others. Rudy is the only Mikeska who serves lamb ribs, and Clem swears by sirloin instead of brisket. Since El Campo is in the heart of the rice belt, local farmers demand Maurice’s tangy rice salad. Jerry doesn’t use garlic (“I just don’t like it”), and Clem’s country-style half-pork and half-beef sausage is smoked over hickory sawdust. Clem says it’s not as spicy as Rudy’s. Jerry and Maurice grind their sausages more finely than Rudy or Clem does. The seasoning is a family secret. Clem’s managers, Virgil Lake, says, “The man makes it himself. I don’t know how he does it. It’s good on everything but waffles.” Live oak provides the smoke in Temple and Taylor, while pecan fuels the fires in Columbus and El Campo. All the barbecue brothers, however, disdain mesquite. “You’ve got to make up your mind what you want to eat—wood or meat,” Clem says. “It smells like diesel fuel.”

With his proximity to Austin, Rudy caters many political affairs. He has served two presidents and cooked for Bill Clements’ 1979 inaugural at the state capitol. For the last eight years, Clem has fed Congress on behalf of Congressman Marvin Leath. Jerry and Maurice rely on Houston for a substantial amount of their catering jobs, even though neither would think of relocating there. “Man, I’m a country boy,” says Jerry.

The Mikeska will remain synonymous with barbecue for at least one more generation. Daughter Mopsie and son Tim are already active in managing Rudy Mikeska’s. Clem is handing over the reins to Stephen, Angela, and Anna. Maurice’s sons, Nick and Gary, and his son-in-law, Jody Vacek, work behind the counter in El Campo, and his daughter, Laurice, does the books. Still, the value of experience cannot be denied. Maurice’s wife, Georgia, explains that the El Campo sons wanted to tear down the funk “old pit restaurant” and its unair-conditioned, grease-encrusted modern dining area to expand the more modern dining room next door. “Over my dead body,” Maurice told them. And it’s a good thing he did. The old building is the only place where the local health inspector will eat.