Years ago, as the sun set over my Dallas neighborhood, taqueros rolled stacked trompos onto its sidewalks with the solemnity of a saint’s feast day procession. The vertical spits were slowly spinning, resembling fire-roasted lighthouses. They beckoned drivers and pedestrians hankering for the vermillion-hued pork. The taqueros dutifully served the meat in griddled tortillas topped with chopped cilantro, white onion, and chile de árbol or creamy, jalapeño-based green salsas. Eventually, the flames were snuffed out and the trompos retreated from the sidewalks, but the impact of the cooking instruments and their tasty products lingered.

For the uninitiated, the term “trompo” might cause some confusion. Sometimes it refers to the cooking device—the vertical roasting spit, similar to what you’ll see gyro meat cooked on. Other times it refers to dishes featuring meat cooked on a trompo, as in tacos de trompo (or the anglicized trompo tacos). The ingredients and names can vary regionally. For example, Mexico City’s tacos de trompo are called tacos al pastor. Other interpretations include tacos de adobada and tacos árabes. And although these classic preparations are certainly popular, the art form of the trompo taco continues to evolve, with taqueros incorporating nontraditional proteins and marinades. In an effort to ease the perplexity, I’m breaking down the different tacos, dispelling myths, and considering the future of the trompo.

Tacos Árabes

Tacos árabes, considered the first trompo tacos, got their start in the early twentieth century, after successful waves of Lebanese immigrants settled in Puebla, Mexico, after decades of political and economic upheaval in their native land at the hands of the Ottoman Empire and a series of wars. With their arrival, the transplants brought their ingredients and culinary traditions, including the vertical spit used to prepare shawarma, or roasted meat. Mexicans adapted the contraption, christened it a trompo (“spinning top” in English), and replaced the lamb favored by their new neighbors with locally popular pork. The marinade (adobo) employed was light in color, with a base of vinegar and citrus bolstered by various herbs. The traditional pita was also tweaked, into something more closely resembling a flour tortilla. When they were done, the Poblanos (residents and natives of Puebla) had transformed shawarma into tacos árabes (Arab tacos). By the thirties, the tacos, typically finished with a chipotle salsa, were served at Tacos Árabes Bagdad and Antigua Taqueria La Oriental.

Although tacos árabes are available in Texas, they are a rare find. Milpa in San Antonio is one of the few taquerias that lists them on its menu. The marinated pork—light almond in color with nutty notes to boot—is served in thin slices on a flour tortilla and garnished with tart crema, mild salsa de chile de árbol, and refreshing cucumber and cilantro. These tacos árabes illustrate how a taqueria can distinguish itself by using a traditional preparation without veering too far from the foundation. Milpa chef-owner Jesse Kuykendall first tasted tacos árabes while attending culinary school in Mexico. The Laredo native was moved by their flavor, certainly, but more important by how mainstream taco culture often erases immigrant contributions. “I really wanted to capture what other people have given to Mexico or have given to [the world],” she says.

Tacos al Pastor

It wasn’t long after tacos árabes were invented that the vertical spit appeared in Mexico City, two and a half hours northwest of Puebla. The Mexico City version took on the name “tacos al pastor”—literally, “shepherd-style tacos”—after the idea that the Lebanese were predominantly pastoral workers and that the spit was used by shepherds in the fields. But the tacos adopted more than just a new name—they underwent a recipe change. The subtle flavors of tacos árabes were turned up a notch with an adobo of achiote, citrus (sour orange is a popular ingredient), and a blend of herbs and spices such as cinnamon, which gives a sweet, comforting finish. The marinade imparts a reddish-orange hue to the stacked slices of pork, which slowly renders until the layers fuse into a luscious cone with a block of pineapple on the top end and an onion on the bottom. The theory is that the citrus juices run down the pork and the onion’s aroma wafts upward.

Two Mexico City taquerias, El Huequito and El Tizoncito, claim to have invented this idealized version of tacos al pastor in the sixties. No matter where they started, tacos al pastor are now ubiquitous. On Calle Lorenzo Boturini, taquerias specializing in tacos al pastor dominate stretches of road. A Boturini taco spot is often the first stop for Chilangos (residents or natives of Mexico City) on the way home from the airport. “The taco al pastor is life,” says Markus Pineyro, owner of Urban Taco in Dallas and a native of Mexico City. Pineyro’s taqueria was among the wave of upstarts that brought Dallas high-quality, traditional trompos on nixtamalized corn tortillas. When he was growing up, Pineyro recalls, his family would visit El Farolito, a popular taco al pastor taqueria, once or twice a week. “I remember my uncle would meet us there. Friends would show up. It’s what everyone did,” he says. “Tacos bring people together.”

Another version of the taco al pastor is the gringa taco. This variation features a flour tortilla bearing pork al pastor and queso blanco. El Fogoncito in Mexico City claims to be the birthplace. As the story goes, in the seventies, two white American women (ergo “gringa”) frequented El Fogoncito and asked for tacos al pastor served that way. Eventually, the option was placed on the official menu, but it’s not necessarily considered a classic Mexico City style like its predecessor.

There are myriad takes on tacos al pastor. Not every taquero applies the same adobo—achiote isn’t a requirement, despite what purists believe. Achiote-free meat is brownish in color, and closer in appearance to that in tacos árabes. Pineapple is also not a requisite for a taco al pastor. The trompo taco at La Pingüica in Mexico City is prepared with alternating layers of pork and white onion. It gives the filling a pop of caramelized sweetness that is juxtaposed with the spicy salsa de chile morita. Regino Rojas served his version of La Pingüica’s al pastor in June and July at his new Revolver Taco Lounge Gastro Cantina in Dallas’s Deep Ellum neighborhood. It was a near dead ringer. Ever the perfectionist, Rojas was unhappy with the result. “Pingüica’s recipe is irreplicable,” he told me. The taquero developed his own recipe by placing some charcoal briquettes beneath the trompo, giving the finished product a unique smokiness.

Tacos al pastor don’t even need to be made with pork. Beef trompos are becoming more popular in Mexico City and San Antonio. The latter city’s best example is the wonderful sirloin trompo at El Pastor Es Mi Señor. “Very few people know that trompos de sirloin are a thing,” says co-owner Brenda Sarmiento.

Tacos de Adobada

This Tijuana specialty translates to “marinated tacos” and could, if you want to be literal, refer to any filling seasoned with adobo. “Tacos de adobada” is mainly a regional term for tacos al pastor, but there are two differences in the cooking and preparation: these are pineapple-free and usually topped with plops of runny guacamole-like salsa. I say guacamole-like because some taqueros take a shortcut by using more tomatillos than avocados. This is considered cheating. I have yet to find Tijuana-style tacos de adobada in Texas.

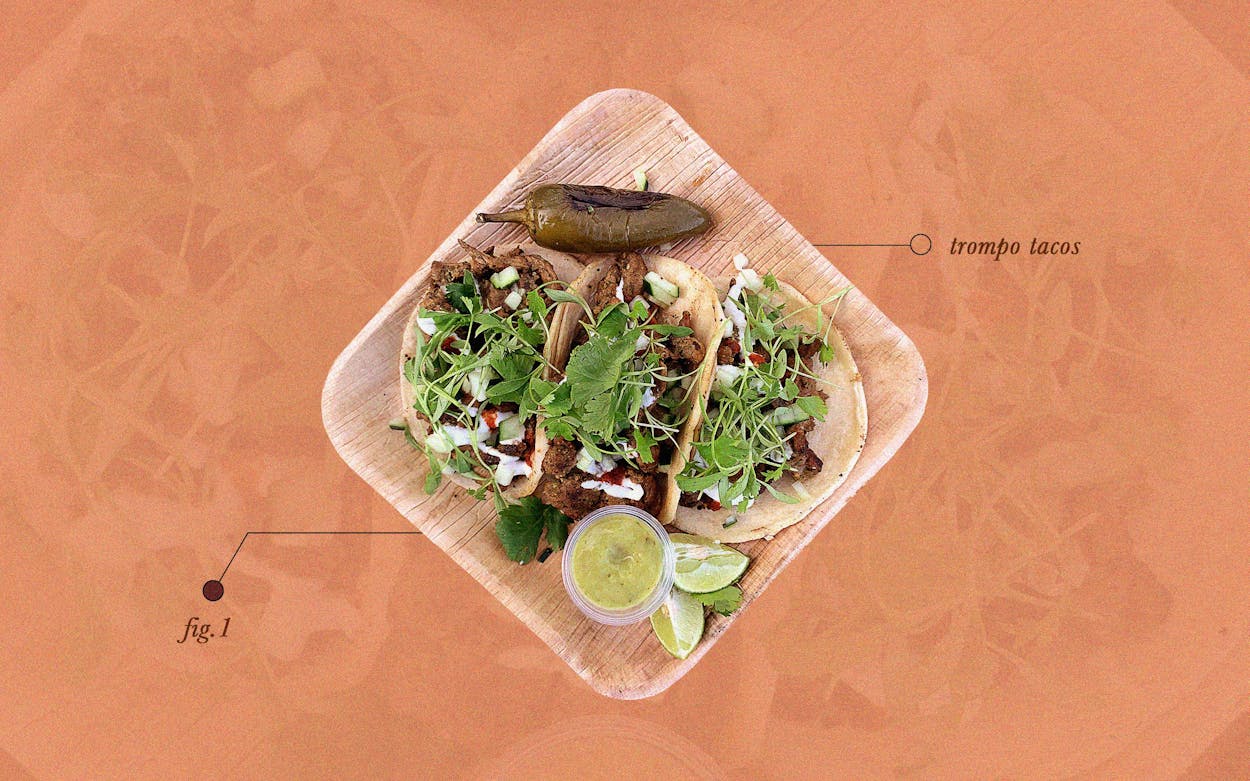

Tacos de Trompo

This cousin of the taco al pastor hails from Monterrey, in the border state of Nuevo León. Its name, taco de trompo, is straightforward, but it went through several permutations before it was formalized. According to scholar Domingo García Garza, tacos de trompo were introduced to Monterrey in 1962 by taquero Julio Reyna. The preparation also was called tacos griego (from gyro and Greek) and tacos Doneraki (from doner kebab and Doner Iraki), their Middle Eastern provenance front and center. It wasn’t until the 1980s and ’90s that tacos de trompo cemented their permanence in northern Mexico and subsequently in Texas cities like Houston and Dallas, which have large populations with roots in Monterrey.

The pork is usually seasoned with a paprika-heavy adobo, giving it a showstopping orange color and a smoky, slightly spicier flavor. The taquero places sliced pork onto well-oiled tortillas on the griddle. After a minute or two, he flips it pork side down, allowing the meat to further crisp and adhere to the tortilla. Perhaps the prime example of the style in Texas is at Dallas’s Trompo. Owner Luis Olvera, a native of Oak Cliff with parents from Monterrey, says that while tacos de trompo are a staple of the neighborhood now, they were a rarity when he was young. “I ate them growing up, spending summers and holidays in Monterrey, but they were absent in Dallas until the late nineties and early aughts,” he says.

Tacos de trompo are not garnished with pineapple, but they do get a flurry of chopped raw white onion, cilantro, and a salsa of choice. I prefer Trompo’s orangey chile de árbol.

The Future of the Trompo

The use of pork instead of beef and the doing away with an achiote-based adobo were only the beginnings of the growing diversity of trompo tacos. As featured in Netflix’s Taco Chronicles, restaurant owner Roberto Solís created al pastor negro in 2012 and began serving it at his taqueria, Kisin, and his restaurant, Mercurio. The blackened tower of pork is marinated with recado negro, a Yucatecan adobo composed of charred ingredients, including dried chiles and burned tortillas. It’s visually stunning. Since the release of the show, the black-hued trompo has become popular. Jaime Hernandez served it at his now closed taco trucks La Fonda de Jaime 2.0 and Aroma in San Antonio.

Vegetarian-friendly trompos are also popping up. One example is Urban Taco’s mushroom version, marinated in the same adobo as the taqueria’s standard trompo. Its chew is uncannily similar chew to that of pork. “Customers kept asking for a nonmeat version, so we tried something that mimicked the texture of meat,” Pineyro says. Another option is the cauliflower trompo at Taconeta in El Paso. The stacked whole cauliflower heads are drenched in a brilliant poblano chile–based adobo. The aroma is floral but the bite is very much like meat.

In 2013, at Revolver Taco Lounge, Rojas invented the octopus trompo, which he finished with a blowtorch. It has been replicated at Evil Cooks in Los Angeles for its Poseidon taco, and in Mexico City at Daniel Silva’s restaurant, Mariscos El Paisa. “I need to push myself. I need to experiment,” Rojas says when asked what inspired the octopus trompo. It’s this spirit that gives tacos de trompo—and Mexican food in general—the tentacle-like reach to burst boundaries and surprise.

- More About:

- Tex-Mexplainer

- Tacos

- Mexico

- San Antonio

- El Paso

- Dallas