It is the farthest corner of Texas, if not physically then at least in spiritual and psychic terms. Here, where the mighty Rio Grande pirouettes upward, shifting its trajectory from the south toward the east, cutting through ancient mountains on its six-hundred-plus-mile run to the Gulf of Mexico, is the big bend that defines this majestic, stark land, a country whose lofty peaks and dramatic canyons and dazzling striations beg exploring and belong to no one. Though people have passed through these reaches for more than 10,000 years, from Clovis-era tribes and nomadic bands of Chisos Indians to the Comanche and eventually Anglo ranchers, the area defies all human claims on it. It’s of no surprise that sixteenth-century Spanish explorers, confronted with the region’s vastness, labeled it el despoblado. The uninhabited. It could have been difficult to imagine this wild country as a park, let alone a national one—its plants are too thorny, its washes too otherworldly, its buttes too strange-looking. But for certain Texans during the late thirties, such as Walter Prescott Webb, who worked as a consultant with the National Park Service, this “earth-wreck,” as he described it in 1937, deserved precisely that demarcation. “If it were thickly settled, it would be out of the picture,” he wrote. “Because it seems to be made up of the scraps left over when the world was made, containing samples of rivers, deserts, sunken blocks of mountain and tree-clad peaks, dried up lakes, canyons, cuestas, vegas, playas, arroyos, volcanic refuse, and hot springs, it fascinates every observer.” A state park already existed in the area, and the Civilian Conservation Corps had been working on trails; soon fellow boosters, like Amon Carter, had persuaded Texas legislators to purchase 600,000 more acres of ranch land and turn it over to the feds. Big Bend National Park was established in 1944. Seven decades later, it is one of the least visited national parks in the country—beauty notwithstanding, it’s just so damn far away from everything. But that distance from civilization is what makes its hold so powerful; I know, because after more than ten years of visiting the park, I am still compelled to return, over and over again. In fact, early this year I spent nearly three weeks in Big Bend with the goal of putting together a field guide that would inspire every Texan, from casual adventurer to seasoned backpacker, to get out and visit (or revisit) this natural resource of ours. A few others who know of Big Bend’s wonders—Matt Bondurant, Sterry Butcher, James H. Evans, Naomi Shihab Nye, and John Spong—also contributed firsthand experiences. Because we all know this: whether you’re pausing at the famous Window or climbing up Pinnacles Trail or navigating the rapids of the lesser-known Mariscal Canyon, this land of cracked earth, of dancing shadows, of endless skies, will change you.

Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive

Given the hours it usually takes to drive to Big Bend in the first place, it may seem counterintuitive to encourage more time behind the wheel. But the thirty-mile Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive, named after the park’s first superintendent, offers such a spectacular sense of the terrain that you may forget you’re even in the car. Maxwell, who helped design the route, knew this. In 1968, sixteen years after leaving his post and moving to Austin, he wrote that no visit to his old stomping grounds could be complete without a drive west of the Chisos Mountains.

The open desert of the Sierra Quemada and its striking formations—Mule Ears Peaks, Goat Mountain, Burro Mesa—are indeed stunning, as I saw for myself one afternoon in early spring. The sinuous road took me over hogbacks and around hoodoos, the shifting shadows and post-rain blooms adding surreal splashes of color. Big Bend bluebonnets nodded in the breeze. Coyotes ventured out, in search of that evening’s meal. Dusk and dawn are the best times to spot native denizens, and as daylight faded, I was treated to a safari of golden eagles, scaled quail, jackrabbits, roadrunners, javelinas, and even a fat black bullsnake on the sun-warmed blacktop.

The abandoned structures of a couple of homesteads (Sam Nail Ranch, Homer Wilson Ranch) as well as a few roadside exhibits gave me an excuse to stretch my legs. I made a mental note of the many trails—such as the lowlands path to Mule Ears Springs—that I would have to investigate another day, steering instead toward the Castolon Historic District, a former cavalry outpost where I’d be able to buy a cold drink. On my way back, I pulled over for one final stop, at Sotol Vista Overlook, a high bluff with a 360-degree view. To the southeast, the land is dominated by spiny-bladed sotol plants, whose bulbs are sometimes roasted for food; sotol also gets distilled into the eponymous alcohol, a relative of tequila. I might not have been drinking, but the orange-and-purple sunset left me intoxicated all the same.

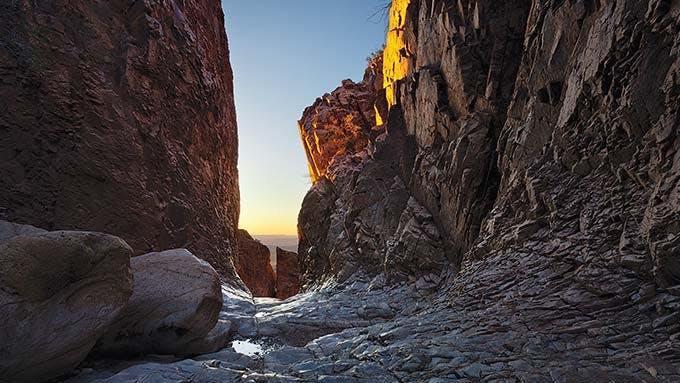

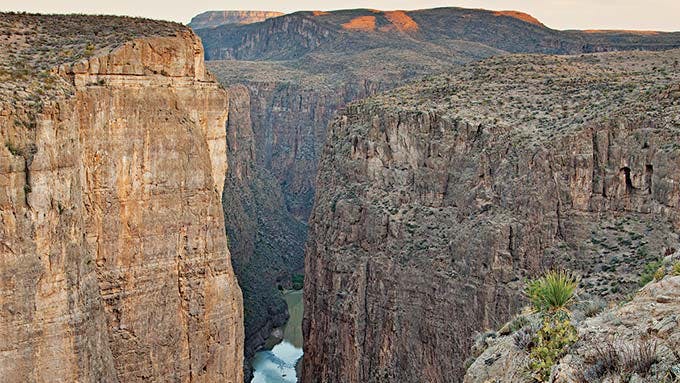

Santa Elena Canyon

Few sights rival the view upstream into the 1,500-foot gorge known as Santa Elena. Its limestone cliffs and rocky depths deterred explorers until 1899, when geologist Robert T. Hill, working on behalf of the U.S. Geological Survey, headed to Big Bend to take on the “longest and least known” stretch of the Rio Grande. He and a team of five made their way through the canyon by dragging boats over rock slides; it took three days to cover seven miles.

Fortunately, modern-day outfitters have simplified canyon exploration, and today you can sign up for a catered float from Lajitas or rent a canoe and paddle the slot independently. (At low water, you can “boomerang” from just downstream to a small side canyon two miles upriver and back.) But there’s also the easiest approach: on foot, which is how I got there. The trailhead lies at the end of Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive; after a quarter mile I joined an ad hoc crew of hikers—from Louisiana, China, Germany, and who knows where else—marching merrily up the concrete path. We came over a bluff, where seashell fossils dotted the rock wall, a reminder that the ocean once covered much of this region. The path then turned to dirt and dropped to the river, prompting oohs and ahs that echoed off the canyon’s walls. Swallows and songbirds hung in the breeze. I found a spot to sit among the river-worn boulders and listened to the gurgling lullaby of the Rio Grande.

Hot Springs Historic District

“The desert will scour your soul,” wrote the cantankerous environmentalist Edward Abbey. But not everybody who comes out to Big Bend, an area Abbey knew well (his classic Desert Solitaire can be purchased at Panther Junction), is looking to get roughed up. Fortunately, there is the Hot Springs Historic District, where channeling the spirit of the wild is as easy as stripping down to your swimsuit. Here, at the end of a short hike, you will find a primitive spa of sorts, where a spring pumps a steady stream of 105-degree mineral water into a tank on the banks of the Rio Grande.

The tank and a few abandoned cabins are what’s left of a resort developed by J. O. Langford in 1910 and sold to the park in 1942; the Mississippi native sought out these therapeutic waters near Tornillo Creek to help cure his recurrent bouts of malaria. Judging from the rock art in the area, he was not the first bather; pictographs and the stain of smoke on the surrounding fissured cliffs attest to centuries of others. When I arrived, after exploring the nearby overlook, I found a prim young couple and a middle-aged RVer already bobbing in the water. But they soon left, and I basked alfresco all alone, my soul and muscles restored.

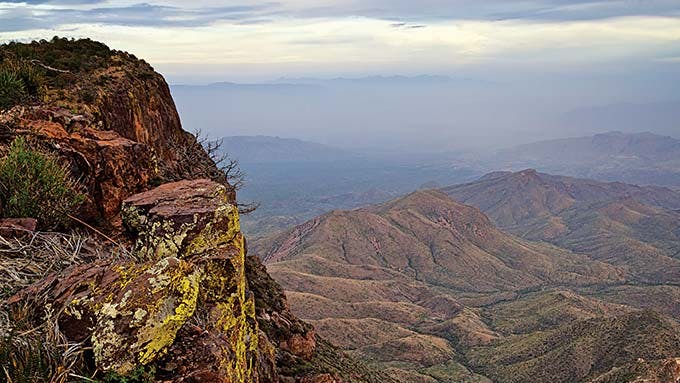

Emory Peak

At 7,832 feet, Emory Peak is not the highest point in Texas, but it is the highest in Big Bend, which means it should grab every capable hiker’s attention. Yes, it’s a steep, five-mile climb not for the faint of heart, but the bird’s-eye perspective from this stark lookout, reached by an ascent that begins just off Pinnacles Trail, is so ridiculously sublime that you’ll quickly forgive the radio antennae and solar panels that cap the peak (yeah, they’re ugly, but ultimately beside the point).

Returning from an overnight in the mountains, I stowed my backpack in a bear-proof box at the Pinnacles split, grabbed a water bottle and a pocketful of snacks, and started up. Black clouds loomed to the east, but I kept my eyes on the trail, surprised to see Cretaceous snail and clam fossils similar to those at the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon. Rising above the tree line—and I’ll admit I was huffing and puffing by now—I was greeted by rays of sun slanting through the rolling cumulonimbus on the horizon, a painterly scene worthy of J. M. W. Turner. Then it was a rough scramble over a stack of fractured boulders to the peak, where my efforts were rewarded with an eternal view. Like the extinct Quetzalcoatlus northropi, a giant flying reptile that once thrived in Big Bend,

I felt myself a creature of the sky.

Lower Burro Mesa Pour-Off

Thanks to Big Bend’s past—volcanic activity, persistent tectonic pressure, erosion—each of its canyons is as unique as a fingerprint. At the Lower Burro Mesa Pour-Off, a one-hundred-foot seasonal waterfall has washed away the tuff, or solidified volcanic ash, leaving behind a spectacular, easy-to-reach box canyon. The area was once home to wild donkeys, which explains the name; access is by a dusty half-mile march across the pebbly, low-lying Javelina Wash.

On my visit, wildlife was in short supply and the pour-off was dry, but the vertical canal still testified to the area’s geological history. Slowing to a stroll, I scanned the red-skirted rocks, carefully avoiding Spanish dagger—an aptly named pointy-leafed yucca—and marveling at the stubbornness of mesquite, whose taproots can reach down more than a hundred feet, an insurance policy against the scorching sun. I was then happily interrupted by two tykes piling rocks near the trail; as I pondered the deposition of the canyon’s fault lines, they appeared intent on seeing who could build the taller tower. When I ducked into the shade of the canyon walls, they, along with their parents, joined me, and our eyes traced the walls together. There was no climbing, no complaining, just shared wonder.

Lost Mine Trail

For a lot of my neighbors in Houston, the very notion of climbing 1,100 feet over two and a half miles is reason enough to have one’s head examined. But what do they know? Lost Mine Trail’s terrain may be rugged, but you don’t have to be an expert to tackle it. Switchbacks lead up through a cool forest of mixed oak, pine, and red-bark madrone—a line of trees that marks the start of a mountain ecosystem unique to Big Bend—and loaner booklets available at the trailhead offer lessons on the other flora and fauna you’ll encounter, including the drooping (or weeping) juniper, a wilted-looking specimen found nowhere else in the U.S. Then there’s the exhilarating finale: a wide stone saddle at 6,850 feet, from where you can stare out in all directions.

There’s so much territory to cover in the park that, as a general rule, I avoid retracing my steps, but a recent visit to this apex prompted me to rethink my strategy. To the southwest rose the backside of Casa Grande, a massive volcanic butte that stands guard over the Chisos Basin; to the southeast stood Lost Mine Peak, where rumors of secret stores of gold and silver ore, discovered by the Spanish and then hidden by Indians, have prompted many (fruitless) searches. Exhilarated by the jutting cliffs and top-down view into lush Juniper Canyon as well as by the sudden appearance of a red-tailed hawk, I quickly reversed another rule: my moratorium on selfies.

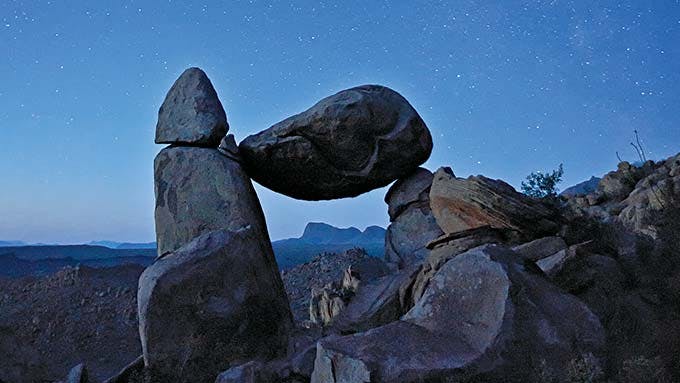

Balanced Rock

Exploring the park’s rugged landscape can sometimes take more determination than your average second grader can muster. Not so when it comes to Grapevine Hills, where jagged outcroppings and a field of misshapen rocks evoke the worlds of Dr. Seuss. A six-mile drivable dirt road drops you at the trailhead, no sweat, and then it’s just a mile hike to Balanced Rock, an east-west window created by an Econoline-size boulder that’s poised atop two stone pillars. From up here, you’ll catch sight of an army of mineralized rock figures basking in the sunshine like lopsided Bar-ba-loots waiting to march west across the arid Tornillo Flat; the Dead Horse Mountains rise in the distance, so named by an early surveyor who lost his favorite horse when it fell from a cliff. (The sun can be brutal, so bring water.) There are plenty of natural benches for resting, but given the trippy, lunar-like appearance of the eroded laccolith (the dome-shaped igneous rock that makes up these hills, related to the much taller Devil’s Tower that figured in Close Encounters of the Third Kind), you’ll be tempted to scamper around like a mountain goat—or a seven-year-old.

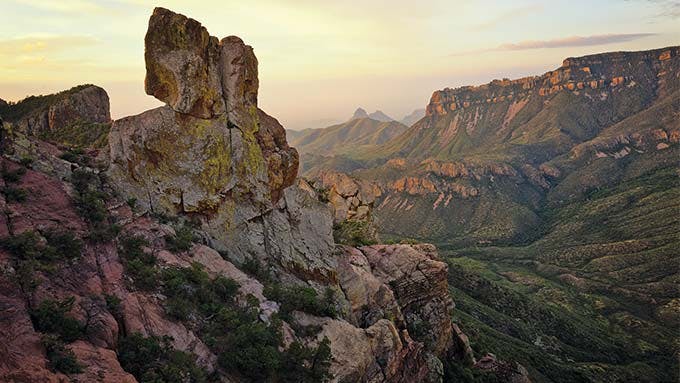

South Rim Loop

You can keep your Grand Canyon, Arizona. We’ve got our own South Rim. Here, atop the cliffs of the Chisos Basin, along a bruising circuit that fitness freaks tackle in six to eight hours, you can peer up to one hundred miles into Mexico. Taking in the mountains that stretch into Chihuahua and Coahuila is a stupefying and, better yet, often private exploit—unlike at that other South Rim, which is bounded by blacktop and gets ten times the annual visitors.

I considered this while standing, very much alone, near where the southeast and southwest portions of the rim converge, ten miles into my hike. Across the desert before me lay an array of strange formations, like figments of Salvador Dalí’s imagination. The dun-colored prong of Elephant Tusk stood to the west, while a sliver of silver beyond the hills hinted at the Rio Grande. In the distance, I could also make out Mexico’s Sierra Ponce, a huge butte twenty miles away marking the edge of the Terlingua Fault.

Sweat and determination are really the only way to reach these heights, and I’d arrived at this overlook via the tough Pinnacles Trail. Though the fourteen-mile South Rim Loop can be conquered in a day, I intended to camp so as to bask in this “sky island,” an ecological designation for the vestigial mountain forest that features native trees such as the Douglas fir and Arizona cypress. The Colima warbler, a bird found nowhere else in the U.S., also nests in these parts. It was too early in the year for it to make an appearance, but as I settled in, I heard the crunch of hooves; a Carmen Mountain white-tailed buck, a species adapted to the high country, was strutting behind me. I smiled. A trek into the upper Chisos is a Texas rite of passage.

The Window

The famous window, that vertiginous notch in the Chisos Basin, is so spectacular and relatively simple to reach that the hike to it can feel a little like cheating. It’s worth noting that there is a short paved path from the park’s lodge to a view onto the Window, but that’s nothing compared with what you’ll find by tackling the five-miles-plus trail (out and back) to the pour-off itself. The moderately descending path, which has trailheads both at the Chisos campground and the lodge, is flanked by oak forests and crisscrosses grooved and cracked limestone, the same as can be found along the Rio Grande, a dozen miles away and two thousand feet below. The trail finally reaches its lofty terminus at the slick lip of a two-hundred-foot cliff; the emptiness of the desert below will relieve any claustrophobia you might be feeling from the crowds of fellow tourists. In fact, if you time your hike for the evening, when twilight washes the scenery in otherworldly oranges, violets, and purples, you probably won’t mind these other explorers at all. I know I didn’t.

Old Ore Road

“If it were hotter out, we’d be soaking in that pool,” said veteran guide Mike Long, who, along with his wife, Crystal Allbright, was leading our thirty-mile bike ride down Old Ore Road. The dirt trail, once a route for miners to ferry silver and zinc out from the Dead Horse Mountains, is popular among two- and four-wheeled explorers alike, not least for its side trips; the pool in question, known as Carlota Tinaja, was a water hole we’d stopped to investigate. The hollowed bedrock was filled with rainwater and slimy algae. I figured Long was kidding.

On the other hand, I could imagine feeling desperate enough out here to jump into the green gloop. Long, who owns Terlingua outfitter Desert Sports, was pedaling with Allbright on a tandem bike with 29-inch knobby tires, and they’d been kicking my butt for the past twenty miles. And though they’d invited a friend along, a winter Texan who owns a bike shop in Ontario, to ensure I didn’t get dropped, I was nearing my limits. The south-to-north traverse, with a two-thousand-foot plunge in elevation, doesn’t translate into epic downhills (as my guides cheerfully pointed out), and for every adrenaline-boosting swoop and dip, there was a grinding climb. Winded, I imagined the ocotillos as my fans, cheering me on with their spindly arms. Thankfully, the views across Tornillo Creek, a tributary of the Rio Grande that crosses these badlands, offered a distraction, as did the white-banded cliffs of Sierra del Carmen. Happy that my companions were still in my sights, I focused on the cold beer that awaited me, a winning alternative to a stale splash.

Pine Canyon Trail

The tick-tick sound of moisture I’d been hiding from in my tent turned out to be an unexpectedly beautiful surprise: frozen flurries, falling onto my nylon tarp. I unzipped the flap to find a ghostly dusting of snow on the tawny grasses, sotol, and prickly pear. I shrugged off my warm sleeping bag to take advantage of this meteorological gift.

I’d camped near the trailhead for Pine Canyon Trail, a lonely path that enters the outer Chisos from the east and skirts the base of Crown Mountain, eventually arriving at a waterfall. Filled with ponderosa pine and home to rare birds such as the flame-colored tanager and the Colima warbler, these canyon woodlands have remained unchanged for so long that they are considered a relic from the last ice age. Designated a research natural area, Pine Canyon has been the subject of watershed studies and wildlife surveys, offering clues to how human presence has altered the rest of the region. As I walked, my own steps felt like an exercise in time travel, the snowy present offering a glimpse of the icy past. I marveled at the powder-crusted madrone, their branches dangling with red berries; when the canyon revealed its famous falls, the pour-off appeared lacquered in crystal. Icicles snapped and shattered overhead, an unsteady rhythm joined by the rude cry of scrub jays in the pines. Leaves and their stems in the out-running stream sparkled like Bulgari jewelry, each bit of debris encased in ice.

Mariscal Canyon

“You couldn’t pick a much harder place to get to,” said Zach Hubbard, the guide who was helping me navigate a two-day paddle down Mariscal Canyon. Simply getting to the river had been a challenge: we’d met early in Terlingua, then headed across the park until we reached a backcountry stretch that took two more hours to cover before reaching the put-in at Talley Camp. After a quick lunch at the base of Mariscal Mountain, where dusky rocks glinted with fool’s gold, Hubbard piled supplies (including a fire pan and a portable privy) into a twenty-foot canoe. Happily, as we slipped the boat into the lapping current, the rigors of the road were quickly forgotten.

It took just a few strokes before limestone cliffs more than a thousand feet tall crowded out the horizon, leaving a mere ribbon of blue overhead. I scanned the walls, pocked with dark caves, and listened to the canyon wrens. Located near the 45-mile stretch of river known as the Great Unknown, Mariscal is the most remote of the Rio Grande’s gorges; our ten-mile float followed the park’s namesake bend. We had only birds and belly-flopping beavers for company.

Breaking the quiet, Hubbard instructed me to paddle as we neared the canyon’s handful of rapids, the most dramatic being the Rock Pile, where boulders force the current to split and boil, a reminder that the tectonics of West Texas are a work in progress. Out of the danger zone, we then beached the canoe to explore Hermit’s Cave, scrambling up to a series of stone alcoves where, the story goes, a Vietnam draft dodger lived long ago. We looked back up the river. Riffles caught the fading sunlight, red dust coated the canyon walls, and the mountains appeared to kneel at the water’s edge.

That night we camped on the banks of Cross Canyon, a notch that runs perpendicular to Mariscal. The stars glowed like sequins, and in the morning, rufous hummingbirds buzzed us awake. The takeout at Solis was only five miles from our camp, but in the end, our journey felt monumental.

Metate Camp

I’d intended to cross the Mesa de Anguila—a plateau on the far southwestern edge of Big Bend—to reach Entrance Camp, at the head of Santa Elena Canyon, where I knew that sandy shores would be the ideal spot to pitch a tent and enjoy the sunset. I’d been told this far-out zone gets few visitors, which held even more appeal. But, like an idiot, I’d left my map in the car, and now I found myself alone on the flank of La Mariposa peak. Too far from the trailhead to turn back, I faced a choice. To my left, a treacherous incline led to a high notch; to my right, a few cairns showed a rocky descent. Worried the climb might dead-end on the serrated ridge, I imagined the cairns had been placed by a well-meaning soul facing the same dilemma.

I followed in the unknown Samaritan’s footsteps.

Getting lost is no fun, but this was different. I had plenty of water, and I discovered seeps in the rocks along the trail should I run out. As I unwittingly headed away from my intended camp, I entered a hushed basin; the False Sentinel formation and other hoodoos stood silently above the grasses. Reaching a willow-studded ravine, I was struck by the smell of creosote and the vaguely lemony scent of the Rio Grande. Over a hill lay Metate Camp, where telltale holes dotted the rocks upon which local tribes once ground their grains. I might not have been on target, but I’d ended up right where I belonged.