The end of a year is time for reflection, to cheer victories and lament losses. And sometimes those losses are quite palpable, like the death of loved ones who won’t be coming into the next year with us.

In 2014, Texas saw the passing of some politcal, cultural, and business giants—Robert Strauss, Johnny Winter, and Bunker Hunt, just to name a few—and great tragedy reverberated through the state when an allegedly drunk driver crashed through a barricade in downtown Austin during SXSW, killing four people.

But here we wanted to remember a few people whose deaths may not have made the same national headlines, yet whose stories need to be told nonetheless: a man who was a loyal salesman for Lone Star for more than sixty years; a woman devoted to justice to her dying day; and a codebreaker during WWII, among thirteen others. And for those on the list whose fame extended beyond our state’s borders, we share how their time in Texas influenced their lives.

This list is by no means comprehensive, and we know that many others died in 2014 too. Please feel free to tell their stories in the comments, as a way to remember the people who made our state—and our lives—great.

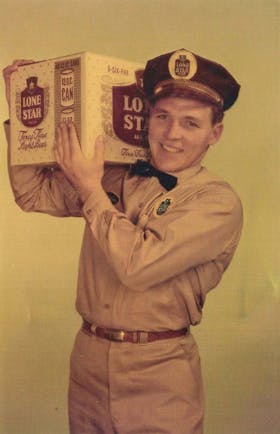

Willard Mercier, 82

He began his career with the brewery in 1950, when he was nineteen, and his first job was as a route driver’s assistant, the guy who did the literal heavy lifting while the driver went over paperwork with store owners and bartenders. If Mercier had been motivated by money, he might have waited to get a route of his own. Back then drivers were paid by the load and made more money than most employees in the brewery’s front office. But Mercier needed a task that put him with people. Community suited him. He’d been a lineman for the Brackenridge High School football team that won the state championship in 1947 and seemed to know half of San Antonio. He spoke good Spanish. And he had that smile. Harry Jersig, the brewery president who ran every aspect of Lone Star’s business with a stiff neck and firm hand, recognized that Mercier’s charm was wasted behind a dolly. In 1956 Jersig handpicked Mercier to move into sales.

Initially he worked locally, building Lone Star’s San Antonio market share to more than 50 percent. When Jersig decided to expand Lone Star’s reach, he grew Mercier’s territory. Some of their efforts were more successful than others; moves into Oklahoma and Louisiana never quite took hold, but the distributorships Mercier worked with in tiny towns like Weimar and Hallettsville made Lone Star the number one beer south of San Antonio. In 1971, with Jersig’s blessing, Mercier resigned from the brewery and went to work managing its distributor in Houston, at that time Lone Star’s best-selling market.

His job was to negotiate with retailers, the big-chain grocers and convenience stores, for optimal placement of Lone Star on shelves and in advertising. He achieved that by striking up real friendships, not just with the corporate big wigs who made the decisions but also with every employee under them. He kept his black Suburban stocked with “dents,” the beerman’s term for beer that couldn’t be sold in stores because the packaging had been damaged. His first move during sales calls was always to find the secretaries and security guards and drop off a six-pack of dents. Or if they weren’t beer-drinkers, he’d give items he’d bartered dents to buy: flowers, kolaches and fresh fruit, pumpkins at Halloween and turkeys at Christmas. “He wasn’t buying people,” recalls his longtime colleague Jerry Retzloff, “he was being nice to them. They could tell the difference.”

Over the decades, the industry changed radically around him, most notably by ever-increasing consolidation. Jersig sold Lone Star to Olympia in 1976, beginning a succession of steadily larger owners, none of which were native to Texas. Each new corporate overseer brought its own people, and each time a few more old Lone Star lifers fell away. But never Mercier. The new owners needed his network.

Even as his Houston distributorship grew to take in other beers, Mercier kept his own emphasis on the beer he started out with. He called it “riding for the brand,” and that was his first commandment. After a Coors distributor bought his company in the late eighties, a sales manager named Mitch Jameson was sent to Houston to force Mercier to put his energy behind Coors. “They told me I needed to tame him,” recalls Jameson.” Our first meeting was with a chain steakhouse of some sort. He told me that if I’d sit down and shut up, he’d make me a hero.” Jameson decided to learn from Mercier rather than coach him. The next year, Jameson was named the company’s national account salesman of the year.

Mercier retired in 1996, but three weeks later he was back in San Antonio and working for Lone Star. That stint lasted until 2007, when, at the age of 76, he set up a consulting firm. He took on only one client, and from then until his death he never stopped working to get Lone Star as much eye-level shelf space as possible. The beer business looked nothing like the world he’d first entered, but that fact never did slow him down. “Just a couple months before Willard died, we had a meeting with our tech people,” recalls Mike Diezi, one of Mercier’s last protégés. “The IT guy was showing us how to tether our phones to our computers so we could work email on them. Willard was having a hard time with that because he didn’t use an iPhone. The IT guy said, ‘How can you sell beer without an iPhone?’ And Willard said, ‘Son, I’ve been in the beer business a long time, and I never saw a computer sell one case of beer.” –John Spong

Sheila Johnson, 54

Every day, I read dozens of stories from Texas publications, from the major metro dailies to the small-town weekly circulars. The dates of the various stories change, but the content rarely does. Politicians squabble; police make another drug arrest; the local football team does better (or worse) than expected; weather is happening. At this point, even the deaths seem rather mundane: motorcyclist killed on I-35; dispute resolved after heavy drinking, target practice; community mourns sudden passing of 125-year-old volunteer.

Then a news item comes along that’s devoid of puns or splash. Something just completely straightforward, an amazing feat in our modern world of commentary and snark.

Like the Fort Worth Star-Telegram piece I read on April 15 that started, “Woman killed in apparent shootout . . . ”

What followed was a story so quintessentially Texas, it’s impossible not to turn the pain and loss into an abstract glorification of violence, stubborn pride, and true grit. After all, that’s how most of our Lone Star heroes have lived on in legend and tall tales. So why not the same treatment for Sheila Johnson, a 54-year-old, five-foot-four, 110-pound woman who died after being shot multiple times with a .45-caliber pistol?

Based on that story and the multiple personal accounts of Johnson’s life, it would seem that all of our Texas ideals and eccentricities could be packed into this one tiny frame. The Texas spirit personified by a single woman whose passing should elicit not that universal and hoary idiom “Rest in peace,” but rather the battle cry so often used within our borders: “Give ’em hell!”

It was the night of Sunday, April 13. Johnson, who helped run 4A Good Auction—“a country auction barn in the city”—in southeast Fort Worth for thirteen years, was staying late. There’s a good chance she was keeping watch. The auction had recently experienced a string of burglaries—two within two weeks in December, another two in January and February. There was still a .45 slug sunk in the front door from one attempt. Another time, burglars had entered, thrown a sheet over Johnson, and pistol-whipped her until she was unconscious. The police hadn’t done much. So Johnson—“not ruled by fear” and “independent,” as friends and family all repeat like a Greek chorus—began taking it upon herself to visit the auction late at night, or even setting up camp inside until morning.

This time, when the thieves came in through the back door, Johnson grabbed her gun and fought back. She was not one to back down.

“Back in the old days, she would have been one of the gunslingers,” said Johnson’s sister, Karen DePriest. “Like Annie Oakley.”

And like Annie Oakley, Johnson loved guns. Had a whole collection. She was also a tomboy who would later pair her cowboy hat with a little Chanel No. 5. Who really liked her Jack, putting away that whiskey neat, with no chaser. Whose go-to meal at the local diner was as classic as it gets: roast beef, mashed taters, green beans, and gravy. Who was kind but wouldn’t take no guff.

Johnson got her first taste of Texas early on, coming down from the family home in Leavenworth, Kansas, to study drama at Austin’s St. Edward’s University. After that, she roamed. She joined the Air Force in her late twenties and was stationed in Germany. There was time spent in Memphis, too, before returning to Texas. First to Arlington and then Fort Worth, where she began working at the auction house. It became a second home to Johnson.

“She would outlift—outwork—the football players that would come from O.D. Wyatt [High School] that we worked with,” 4A co-owner Bob Crowder had told the Star-Telegram. Picking up items for the auction, three-hundred-pound men would simply stand and watch as Johnson moved entire refrigerators twice her weight by herself. Once, Johnson and 4A’s other co-owner, Beverly Carter, had to pick up a “llama named Obama and the son of Obama the Llama.” Obama the Llama was kind and gentle; his son was not. After two hours of lassoing, Johnson finally got hold of him. Heels in the dirt, Johnson was screaming, “I’m not gonna let go!” as the son of Obama the Llama dragged her through the pasture. Again, she was not one to back down.

“When I was a kid, I had a book of Pecos Bill, and it had this tornado and this guy on a bucking bronco with his six-shooter guns drawn,” Crowder said. “That’s the thought I have of Sheila.” Crowder paused for a moment. It was unclear whether he meant to compare Johnson to Pecos Bill or the twister. From the sound of it, she could have been both forces at once.

Sheila Johnson: frying pan–sized but would charge hell with a bucket of ice water; strong as a high school linebacker; tough as nickel steak; independent as a hog on ice and as stubborn as a son of a llama.

Even the sparse details of her death—the “shootout”—provide perfectly portioned ingredients for legend.

The night she was killed, Johnson was sitting on the auction house stage, which had, over the years, “become kind of her nest, her cozy spot,” as Carter put it. When the thieves entered, Johnson sprang to action, emptying the clip of her Marlin, semiautomatic .22 rifle. Maybe the future stories will have her finishing off the bad guys just before dropping down and reciting her own glorious dirge. All we really know about that night is the cause of death—“gunshot wounds of torso,” according to the coroner’s report. The alleged killers are awaiting trial. But she was found the next day, directly behind the auction podium, with the rifle still in her hands. She’d defended her home, the life she’d made. It was her own personal Alamo.

Painful as it is, Johnson’s friends and family instinctively understand.

“At first, it was like, ‘Oh, my gosh what were you thinking?’” DePriest said. “But then it’s like, ‘Well, that would be her.’ You know, ‘This is my place, this is our livelihood, and nobody can come in here and take it.’” –Jeff Winkler

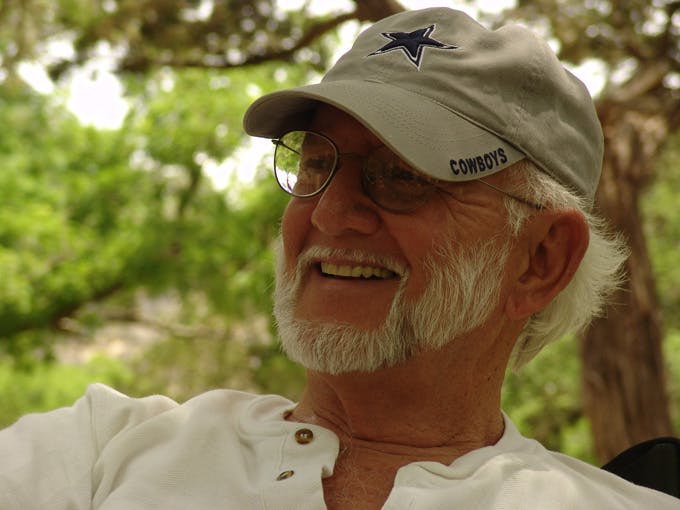

Rod Kennedy, 84

Not that rain ruined Kennedy when he launched the Kerrville Folk Festival in 1972. The inaugural festival, which took place over three nights, was sheltered in the Kerrville Municipal Auditorium, where acts ranging from local “cosmic cowboy” Michael Martin Murphey and revered bluesman Mance Lipscomb to national folk icons Carolyn Hester and Peter Yarrow played to a sold-out house. The next year, Kennedy added another night of performances, but still the 1,200-person auditorium sold out. With music-lovers clamoring for more tickets, Kennedy decided to move his fledgling festival to a larger outdoor venue.

Kennedy purchased a sixty-acre tract of land nine miles south of Kerrville, diplomatically decreeing his new stead the Quiet Valley Ranch in hopes of soothing concerned neighbors. The start of 1974 found Kennedy hard at work, clearing cedar stumps and building a stage for the third Kerrville Folk Festival. Another crop of eclectic musical talent expertly picked by Kennedy drew six thousand fans over four days to Quiet Valley. Attendees and interested onlookers hailed the event as a success.

But Kennedy barely broke even. That was only the beginning of the tribulations the festival and its founder would face. The next year the rain fell—hard.

Rod Kennedy was born in Buffalo, New York. Music surrounded him from his earliest days. His father would sing while his mother played the ukulele on their farm in Amherst. The young Kennedy sang in church choir and frequented the local movie theater, where big bands would play before a film started. When he was fourteen, he explains in his autobiography, Music From the Heart, his mother followed work to Wheeling, West Virginia.

In Wheeling, Kennedy scrapped with sons of local coal miners who mocked him for singing in public. His world radically shifted again when his mother accepted an offer in New Orleans. From the back of his friend’s Cushman motor scooter, Kennedy discovered the French Quarter, a place electrified by a whole new world of music: jazz. His musical education steamed ahead when he and his mother relocated to Houston. Here Kennedy fell in love—both with a suntanned brunette and with the sound of Bob Wills’s fiddle. Kennedy returned to Buffalo to finish high school, but this exposure to various musical forms across America, especially his time in Texas, made him want to pursue music.

Hired as a singer by a big-band orchestra in Buffalo, the sixteen-year-old was soon managing the band, doing everything from booking gigs to stage production. He was focused on fostering the city’s jazz community when he was summoned by Uncle Sam to Korea. As a marine, he survived months of brutal trench combat, vowing on the voyage home to, as he says in his autobiography, “devote the rest of my life to something that would benefit a lot of people.”

Back from war, Kennedy attended the University of Texas while working at KHFI, the first FM station in Austin. He later bought the station and added variety to its classical-music programming. He helped raise the funds for KUT’s first broadcast building and was instrumental in bringing the second television station to Austin. He combined his love of sports cars and live music by opening the Chequered Flag Club, a venue serving up roast beef sandwiches and musical talent.

His palate for traditional styles of music like ragtime, Dixieland jazz, bluegrass, and classical compositions combined with a keen taste for modern country, folk, Tejano, and blues, made him the most sought-after concert promoter and producer in the state. But it was his affinity for well-crafted songs that spurred him to create the festival, which has become the shining achievement of his career in the arts.

Hard rains fell on seven of the first nineteen Kerrville Folk Festivals held at Quiet Valley Ranch. Still, Kennedy weathered on. Under his stewardship, the festival not only maintained a level of musical excellence, but by the fireside of late-night sing-alongs, an atmosphere of “spiritual optimism” flourished among Kerrverts (as festival-goers are called). It was this unique sense of community and a powerful devotion to music that gave Kennedy the fortitude to withstand those early floods.

The Kerrville Folk Festival is now the longest-running festival of its kind and has expanded into an eighteen-day event that draws a crowd of more than 30,000. The festival has been the launching pad of countless musical careers. On Kennedy’s eightieth birthday, many of these artists, including Robert Earl Keen, the Flatlanders, and Eliza Gilkyson, paid tribute to the man whose festival has been so important to their music.

The stage at Quiet Valley Ranch still bears Rod Kennedy’s name, but the true testament to his legacy can be felt in the festival’s one-of-a-kind atmosphere and heard every time a group of fans and songwriters gathers around the Ballad Tree. The music lives on. Rain or shine. –Christian Wallace

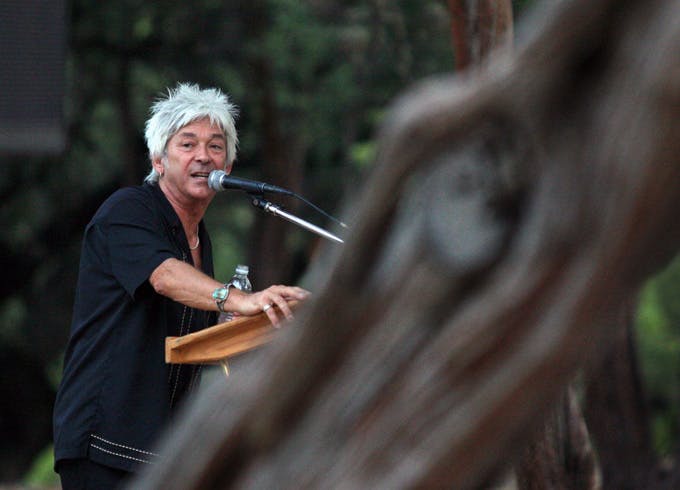

Ian McLagan, 69

He died on December 3, 2014, of complications from a massive stroke. The doctors told us that his cognitive functions were knocked out in seconds. The part of the brain that made him a rock and roll genius had shut down, and he was unaware of any pain.

I started playing music with Mac in early 1994. For twenty years, I was a card-carrying member of Ian McLagan and the Bump Band. Mac used to say, “Once a Bump, always a Bump.” So I guess I’m still in the band.

Being in a band is where Mac always wanted to be, it’s where I always wanted to be, and this was an understanding between us. It’s still hard for me to believe that there is not another gig, session, or rehearsal on the books. I miss him, and I will miss the pure experience of playing with him more than I know how to say.

I felt like I was exactly where I was supposed to be on those many nights when we were rocking it up on one of Mac’s songs, like “Your Secret,” or playing the weave on the outro of Ronnie Lane’s “Glad and Sorry.” “The weave” is the interaction between players in a rock and roll band; it’s the territory where there’s no designation of “lead guitar,” “rhythm guitar,” or “keyboard solos.” Each instrument is playing individually and also supporting the other, as well as the song. Mac told me Keith Richards dubbed this type of playing “the ancient art of weaving.” For prime examples, listen to Mac and Ron Wood playing on the Faces’ track “You’re So Rude,” or Woody and Keith and Mac playing on the Stones’ “Miss You.”

There are also many examples on Live at the Lucky Lounge, the live record that the Bump Band put out last year. Mac and I got pretty good at weaving. “Let’s not have a solo,” he would say, “just a bit of a weave.”

The last show the Bump Band played was bursting with this kind of playing from everybody on stage. It was Jon Notarthomas on bass and Daren Hess on drums, and I remember Mac saying to us after the show, “That was magic! That was just magic!”

So that was a little about Mac, the Bump Band, and myself, a friendship and musical camaraderie that I sometimes still can’t believe. Now let me tell you a bit about the man.

His first band, the Muleskinners, backed up both Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter during some of their early tours of the U.K.

He has a copy of the set list from every show he played with the Small Faces, Faces, and the Bump Band. That’s fifty years worth of set lists.

He has a son from his first marriage, to Sandy Serjeant. His son’s name is Lee, and he gave Mac a granddaughter. Lee is a cool dude.

The best stories you’re going to hear about him can’t be printed here, but many of them can be found in his memoir, All the Rage.

He bounced back from some dark times more than once in his life.

Whenever he was doing a session that had a Steinway piano in the studio, Mac would open it up and sign it when no one was around.

Mac was proud of his band, and he let you know it.

He loved Ron Wood dearly. Every time we would play one of his songs, Mac would introduce it with, “You know what they say, Ronnie Wood if he could, and he always does!”

He loved to cut trails through the woods on his property in Manor.

He loved his brother-in-law Dermot Kerrigan and was always eager to talk about what a great actor he was.

He loved listening to Little Walter, Johnny Johnson, Otis Spann, Bobby Womack, the Louvin Brothers, the Everly Brothers, Bob Dylan, and Muddy Waters.

He loved his wife, Kim.

And one last thing: I was talking to Mac not long ago about raising some money for the next recording project. We were talking about flying Mac’s old friend Glyn Johns over from London to produce. We were going over the costs: flights, studio time, salaries, these kinds of things. After thinking it over, Mac said, “It might just be too expensive to do it this way.”

“You’re Ian McLagan!” I exclaimed. “Someone’s going to put up money for you to record.”

“Scrap, I think you’re overestimating my place in the rock and roll pantheon.”

I laughed. “No, I’m not Mac!”

I’m sure I’m not, old pal. –Scrappy Jud Newcomb

(AP Photo/Jack Plunkett)

Robert Heard, 84

While Heard’s writing career was founded in hard news, he often wrote short stories under the pen name Sam Honey (a tip of the hat to Mark Twain, whom he greatly admired). Throughout his life, he published books through Honey Hill Publishing, a company he started. And though he was the son of a Baptist preacher and a proclaimed atheist, he wrote a book about Mary Magdalene, depicting her as the founder of Christianity.

“Everybody cares to a certain extent what people think of people, but something in him kept him from caring enough to change for people,” Tom said. “He would never change for anyone.” –Kelsey Davis

Edith Sawyer, 93

Maybe it was because after she returned from war, she focused on raising her three daughters (and after that, earning a nursing degree, which she did at age sixty). Maybe it was that she had her hands full spearheading the hospice program in rural areas around Cedar Creek Lake. Or maybe, as her daughter Joanna Kriss hypothesizes, she was simply in the habit of not talking about it. Sawyer knew she could be tried for treason and executed if she disclosed any details of her work during the war, and the practice of keeping quiet about it stayed with her for the rest of her life.

But upon her burial, Sawyer’s role as a Navy lieutenant JG in 1943 surfaced as one of the more defining periods of her life. “When she died, a Navy commander came to the grave site to do a special ceremony for my mom,” said Kriss. “That was when we really started picking up more.” –Kelsey Davis

Ed Sprinkle, 90

He was known as “The Claw” and “the meanest man in football”—and for good reason. A defensive end for the Chicago Bears for more than a decade, the former Texan was infamous for delivering some of the hardest, most devastating hits in the NFL during the forties and fifties.

Although Sprinkle hadn’t been a Texan for quite some time, he had deep roots in the Lone Star State. Born in Bradshaw and raised in Tuscola, Sprinkle distinguished himself athletically early on. At Hardin-Simmons University, in Abilene, he earned multiple letters in both football and basketball, as well as All-Border Conference honors, before transferring to the U.S. Naval Academy, in Maryland, where he continued his football career.

Soon after a successful tryout with the Chicago Bears in 1944, Sprinkle earned his nickname of “The Claw” for the vicious use of his forearms against opponents: spreading them wide in caricaturist fashion to deliver what is today considered an illegal clothesline tackle. In a November 1950 profile, Collier’s magazine dubbed Sprinkle “the meanest” (after all, he did break several noses and even separated the shoulder of a running back with his moves). After his colorful career with the Bears, during which he earned a spot on the NFL’s 1940’s all-decade team and appeared in four Pro Bowls, Sprinkle headed east in 1962 to serve a season as defensive coordinator for the New York Jets.

In late July, Sprinkle passed away in Palos Heights, Illinois, from natural causes. He was 90. –Lauren Caruba

Betty King, 89

In 1988 her dedication was recognized by the Governor’s Commission for Women, which namd her among the Outstanding Women in Texas Government. In 2001 the Lieutenant Governor’s Committee Room was renamed in her honor and the Betty King Public Service Award was established.

Born in Port Arthur and raised in McAllen, King was a lifelong Texan. She attended the University of Texas at Austin, remaining in the city for the rest of her life. King’s activism extended outside the Capitol, as she was a member of numerous civic and philanthropic organizations. King died on December 1 following complications from Parkinson’s and cancer. On December 6, she was buried in the Texas State Cemetery, put to rest among many other notable Texas politicians. –Lauren Caruba

(Photo courtesy of the Texas Senate)

Marilyn Burns, 65

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, Burns lived in Houston for most of her life. Shortly after graduating from the University of Texas with a degree in drama, she auditioned for the role of Sally, the protagonist of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It was Burns’s first lead acting gig, and while she wasn’t especially interested in it at first, director Tobe Hooper’s independent horror film—made as famous by its grotesque scenes as by its horrific shooting conditions—defined her career. She later starred in a number of other slasher flicks, including Helter Skelter and Eaten Alive, and made a cameo in Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation, the 1994 follow-up to her most famous role. She also served on the Texas Film Commission and attended horror conventions, where she entertained fans with stories about the set of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Burns’s ear-splitting screams and horror-struck face remain unmatched even now, forty years after the film was first shown to terrified audiences all over the world. And the lung-busting screeches and squeals belted out by actors in scary movies today are but an echo to the Scream Queen’s legacy. –Hannah Smothers

The North Central Texas College Softball Team Players

Animals We’ll Miss

Miss Beazley, 9, October 28, 2004–May 17, 2014

A void was left in George W. Bush’s Dallas home this May with the departure of Miss Beazley, his beloved Scottish terrier. A fixture in the White House for several years (Bush gave her to the first lady in late 2004), the boisterous Scottish terrier deftly filled the role of first dog. From snuggling with Bush in the Oval Office to bounding toward him across the White House lawn, Miss Beazley clearly held a special place in the former president’s heart.

Miss Beazley was also quite the actress, starring in the ten-minute 2005 film “A Very Beazley Christmas,” alongside Barney (the Bushes’ other Scottish terrier, who died in February 2013). Focusing on Miss Beazley’s first holiday season at the White House, the video features the rivalry between Barney and the newest member of the Bush family, a review of the pooch’s strong poll numbers, and even the first dog’s (fake) debut as a candidate on C-SPAN. “Both of you are an important part of our family, and you have to remember the true meaning of the holiday season,” the president tells the dogs as they sit on chairs in front of his desk. “Now you two run on, I’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Miss Beazley was put down in May after fighting lymphoma. The former president announced her passing on his Facebook page: “She was a source of joy during our time in Washington and in Dallas. She was a close companion to her blood relative, Barney. And even though he received all the attention, Beazley never held a grudge against him. She was a guardian to our cats, Bob and Bernadette, who—like Laura and I—will miss her.” –Lauren Caruba

(AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

Thelma and Louise, 13 months, June 18, 2013–July 29, 2014

Thelma and Louise were partners in crime from the very beginning. When the rare two-headed Texas river cooter hatched at the San Antonio Zoo in the summer of 2013, the turtle was eagerly welcomed by zookeepers, who fielded numerous calls and emails from amateur herpetologists about her. They christened the turtle Thelma and Louise, after the 1991 movie starring Gina Davis and Susan Sarandon (Thelma was the right head, Louise the left).

As a Texas cooter, a species found naturally only in Texas, and the namesake of a film with Texas references, Thelma and Louise was “about as Texas as it gets,” said Craig Pelke, curator of reptiles, amphibians, and aquatics at the zoo.

Just a month after the river turtle’s birth, the strange specimen already had its own Facebook page, which has nearing 8,500 likes and still posthumously shares news on the state of Texas’s turtles. The turtle was also filmed last year for an episode of Nat Geo Wild. Hundreds of children visited the turtle in June to celebrate the birthday of Thelma and Louise, creating cards for the zoo’s most unusual creature. “She was extremely popular. People really enjoyed her,” Pelke said. And with her second head, “She had a little extra element of cuteness to her,” he added.

Although Thelma and Louise was clearly an anomaly (although not entirely uncommon among reptiles, especially turtles and snakes), the turtle lived out its short life with “good vigor,” according to Pelke, swimming around and basking in the sun. Despite “daily intensive care and monitoring” by the zoo, Thelma and Louise died suddenly in late July from complications due to her abnormal physiology, including a lack of growth, an extra lung lobe, and a partially formed second heart. –Lauren Caruba

Goliath, World’s Tallest Horse

If Michael Jordan were to bow up to Goliath, his puffed-out chest wouldn’t have even reached the horse’s shoulder. For once, the six-foot-six Jordan would have been the David in an underdog tale. But no slingshot would have been needed. The horse, a black Percheron who stood at 19.1 hands (six-foot-five at the withers), was a gentle giant.

After being crowned World’s Tallest Horse by the Guinness Book of World Records in 2005, he traveled from coast to coast, making appearances all along the way. Sometimes his presence caused a ruckus in the towns he visited, and police would have to ask that he move along to the next stop on his tour. “[People] were parked all along the road,” said Caroline Dyer, a caretaker of Goliath’s at Priefert Ranch, just south of Mount Pleasant. “They had to basically shut down traffic because everybody was at this one little store in the corner of town, waiting for their turn to see the tallest living horse.”

Radar, a close friend of Goliath’s and fellow Priefert Ranch horse, later went on to take Goliath’s title as World’s Tallest Horse, but the two didn’t allow this to disrupt their friendship. “You never saw one in the pasture if the other wasn’t right beside him, so there were no hard feelings,” Dyer said. “Even though Radar had taken Goliath’s record, they were still pretty tight.”

Goliath passed away from old age in July, but a monument erected over his grave at the Priefert Ranch keeps his memory alive. –Kelsey Davis

Bobby Keys, 70

Few kids first put their lips to a saxophone reed with dreams of playing in the world’s greatest rock and roll band. Fewer still actually get to live that fantasy. But then again, not many kids grow up with one of rock’s greatest legends practicing within earshot of their open bedroom windows. Bobby Keys did.

Keys was born in Slaton, a small town fifteen miles southeast of Lubbock surrounded by cotton fields and Santa Fe trains moving across the caprock. When he was little, he hung around studio sessions with Buddy Holly and the Crickets, fetching them Cokes and bobbing his head to the beat. He was also working on his own skills as a musician, learning to play the saxophone by ear.

At fifteen, Keys embarked on what would become his life as a road musician, leaving Lubbock County with Bobby Vee, a sixties pop star whose own music was inspired by Holly. A year later, while playing San Antonio’s Teen Fair, Keys heard the familiar opening riffs of Holly’s “Not Fade Away” and rushed over to see who had the gall to cover his famous neighbor’s signature tune. It was the Rolling Stones, playing their second-ever American show. Listening closely to the “pasty-faced, funny-talking, skinny-legged” Englishmen, Keys decided that they were actually pretty good. Keys met the band and formed an instant connection with the rockers, particularly Keith Richards, who shared Keys’s love and respect for Holly’s music.

Five years later, in 1969, Keys was at Elektra Studios in Los Angeles laying down sax tracks for the husband-wife music duo Delaney and Bonnie when rock and roll providence intervened. Mick Jagger saw Keys ambling down a studio hallway, recognizing him as the sax player from Texas, and asked him to take a stab at the Stones’s tune “Live With Me.” In one take, the kid from Lubbock made himself an inseparable part of the sound of what is largely lauded as the golden period of the Rolling Stones.

Keys’ style of sax playing has been described as swampy, honking, grimy, howling, and soulful. On what is arguably his most famous contribution to music, the blistering solo on “Brown Sugar,” you can hear the notes almost tearing away from the song, the vibrato flittering wildly and powerfully, like a rag snagged on some barbed wire and billowing in the wind. Perhaps it was the lack of formal training—he never learned to read sheet music—that allowed for the imaginative, reckless style that became his musical hallmark. As Keys told the Austin Chronicle in 2006, “I just stick it in my face and blow.”

Whatever informed Keys’s unique styling, it made him a hot musical commodity for more than four decades. Besides playing on seminal Stones albums, Exile on Main Street, Sticky Fingers, and Let it Bleed, Keys contributed to records by Joe Cocker, B.B. King, Eric Clapton, Carly Simon, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Humble Pie, Joe Ely, and solo efforts by every Beatle but McCartney. The stints when Keys was not recording or touring were short-lived.

Life as a touring musician suited Keys, whose raucous road stories are now as integral to his legacy as his sax playing. Richards relates several wild tales in his memoir, Life, about the antics that he and Keys would get into, usually after a few rounds of Rusty Nails (scotch and Drambuie) and a cocktail of narcotics. There’s the time Keys and Richards started a fire at the Chicago Playboy mansion, the notorious bath of Dom Pérignon (filled to woo a beautiful French gal, of course), and the infamous footage of the two rock stars giggling as they toss a TV set over a hotel balcony in Denver. “Television’s boring anyway,” Keys utters in an accent broad and flat as the prairies he grew up on. (Richards would be the first to say Keys never let anyone forget he was from Texas.)

Often sporting a pearl-snap shirt and cowboy boots, his name engraved on the shining curved opening of his sax, Keys gave the bands he played with a sense of authenticity. He continued to live and play like a rock star right up to the time of his death, on December 2 at his home in Nashville.

Richards offered this in memoriam of his longtime bandmate and friend to Rolling Stone: “[Bobby] told me, ‘I got a heart as big as Texas,’ and I said, ‘Bobby, I think it’s a bit larger.’ He probably wouldn’t want us to be too solemn right now. Basically when it’s all said and done, I’m looking upon this now as a celebration of life rather than a memorial for his death.” –Christian Wallace

(Photo courtesy Bobby Keys’ Facebook)

Harley Clark, 78

But the signal ubiquitous to celebrating UT victory owes its origin to one man: Harley Clark. As Paul Burka wrote for Texas Monthly in 1997:

[B]y 1955 archrival UT had fallen on hard times, made harder by a corresponding rise in the fortunes of A&M. A UT cheerleader named Harley Clark syllogized: (1) A&M has a hand sign, (2) A&M is winning, (3) UT has no hand sign, therefore (4) UT is losing. . . . At a pep rally before the TCU game, Clark held up his right hand in a peculiar way. The index and little fingers were sticking up, while the thumb held down the two interior digits–the head of a Longhorn, Clark said. The creation proved not to be the immediate answer to UT’s football plight, however, as signless TCU won the next day, 47-20.

While this might be Clark’s most famous contribution during his 78 years, it is far from his only one. After earning a law degree in 1962, he was appointed as judge of the 250th Judicial District Court, where his biggest decision on the bench was in Edgewood ISD v. Kirby, when he ruled that the way Texas allocated money to different school districts was unconstitutional.

He resigned from the bench in 1989 and joined the law firm of Vinson & Elkins, which is where he met his wife, Patti. The couple was married on September 8, 1998—an intentional decision, Patti says, because of the way the numbers matched—and their ceremony was held in Booked Up, the Archer City bookstore that’s owned by Larry McMurtry. Patti says the bookstore was decorated with flowers, and McMurtry himself signed the couple’s marriage license as a witness. Returning to Booked Up became an anniversary tradition for the Clarks, who liked to dig through the stacks in hopes of finding a new treasure to add to their collection.

He spent much of his retirement on the forty acres he owned outside Dripping Springs, cultivating an expansive garden, paying special attention to his tomatoes. “He approached it like he did everything else,” Patti said. “He studied and studied until he knew everything he could about tomatoes and really became an expert.”

When he wasn’t tending his land, Clark read his favorite Texas authors, like J. Frank Dobie, Tom Lea, and Walter Prescott Webb.

Harley was 78 when he died in October. He is buried in the Texas State Cemetery, where he is surrounded by some of the writers—and Longhorns—he respected so much. –Hannah Smothers

(AP Photo/Austin American-Statesman, Brian K. Diggs)

Doc McPherson, 95

Considered a true pioneer of the Texas wine industry, McPherson and his colleague and business partner, Bob Reed, began planting experimental grapes in Lubbock during the late sixties, just to see if wine grapes could thrive in Texas. In 1968 he was the first to plant Sangiovese in his “Sagmor Vineyard,” a plot of land that still produces some of the most prized Sangiovese in Texas today. He and Reed established the Llano Estacado Winery in 1976, one of the first post-Prohibition wineries in Texas. Today McPherson is revered as one of the fathers of the Texas wine industry.

Doc left behind a significant legacy for the next generation of Texas winemakers and grape growers to carry on, a group that includes his son Kim McPherson, of McPherson Cellars in Lubbock (pictured left, with his father). “The truth is, we would not be anywhere close to where we are without him,” Kim said of his father’s legacy. “Most people don’t realize how incredibly hard it was. He had a lot of obstacles to overcome. In the seventies, liquor in Texas was dominated by major forces like Tom ‘Pinkie’ Roden of Pinkie’s Liquor Stores in West Texas, Sigel’s Fine Wines and Spirits, and Majestic Liquor Stores. If you didn’t have their support, it wasn’t going to happen. There’s an old saying that you attract more flies with honey than with vinegar. My dad was the honey. He met multiple times with people like Pinkie in the early years. He worked with legislators to get laws passed. He was one of the founders of the Texas Wine and Grape Growers Association.”

Doc McPherson, who grew up in a cotton farming family, served in the Army Air Corps in World War II. He returned to Texas to teach chemistry at Texas Tech University before eventually starting his own vineyard in the High Plains. Two of his three sons, Kim and John, now work in the field he cultivated from the ground up.

“He always wanted to see Texas wines in other states,” Kim said. “To him, that’s what would make this a real industry. He was also serious about finding the right varieties to plant here. He was the first to plant Sangiovese and Carignan. He even planted Tempranillo that was brought over from Spain by a friend in a Volkswagen wheel. Of course, at the time, no one was buying wines like that. If it wasn’t Cabernet Sauvignon or Chardonnay, it wasn’t profitable. But he saw that they flourished in Texas. And now, we’re finally starting to follow his lead.” –Jessica Dupuy