You’d have thought Beto O’Rourke would have begun 2019 feeling pretty good about himself. He’d just finished a senatorial race against Ted Cruz that turned him into a national celebrity and come closer to winning than any Texas Democratic statewide candidate had in two decades. His options seemed boundless: Another statewide run? A Foss reunion tour?

But he started the new year feeling blue. “Have been stuck lately,” he wrote in a blog post on January 16. “In and out of a funk.” On January 19, he saw some kids throwing snowballs outside a Baptist church in Ulysses, Kansas. “Made me think of our kids, and I missed them,” he said, as if he were a traveling salesman forced from home rather than a guy who chose to take a solo road trip through the Great Plains. “Added to the low altitude I was experiencing,” he concluded. On January 24, he filed another dispatch, this time from Taos, New Mexico: “There is always someone, usually on cable TV or Twitter, to remind you how small or stupid you’re supposed to feel.”

After evoking so much love and admiration from his fellow Texans, O’Rourke seemed, inexplicably, to want to be anywhere but Texas—and he seemed, inexplicably, to be having a miserable time everywhere else too. His fans were left sticking pins in a map, tracking his movements. Where was O’Rourke headed? An artist colony in New Mexico? A fundamentalist Mormon compound? Would he soon be found meditating cliffside at the Esalen Institute, flowers in his hair?

The answer proved much worse than any of those things: He decided to run for president of the United States, a position for which he was particularly ill-suited and which no sane person could want. In 2019, Beto O’Rourke got lost in America and lost in his head, and it’s tough to see how he’ll ever find his way back.

O’Rourke’s road diaries were as strange a start to a presidential campaign as this country has seen. It seemed as if O’Rourke hadn’t yet grokked that the office he was now seeking was very different from the one he’d sought the year before. Anybody can be a senator; it’s hardly a real job. But the American president is an emperor, cloaked in immense powers. The stiff formalities and conscious calm that presidents try to exude (at least, before 2016) are supposed to provide reassurance and an impression of stability. Were Americans ready to replace Donald Trump with a three-term congressman with a skimpy legislative record who seemed to be going through a midlife crisis?

Perhaps they had no choice. “Man, I’m just born to be in it,” read the key quote in the April Vanity Fair profile that helped launch O’Rourke’s presidential bid. It was just a few words lifted from a long article, but the idea that O’Rourke somehow felt entitled to the nation’s highest office attached itself to him and never let go. Oh, there’s a presidency available? Well, sure, I guess I could take it!

The memes soon followed. As he campaigned, O’Rourke stood on tables and counters and whatever was available, to address the crowds that came to his early events. He was likely trying to look casual, but he exuded the energy of a substitute teacher who sits backward in his chair to “have a casual rap session” with the kids. He livestreamed a video of himself receiving a dental cleaning, proving that there’s such a thing as too much transparency. He responded to a question from a Washington Post reporter about how the country should handle a critical component of its immigration policy with an honest “I don’t know,” giving the impression that he was unprepared to engage on an issue that should have been central to his campaign. Sometimes he cussed, and sometimes he didn’t cuss, and sometimes his campaign put out merchandise with the cusses censored. None of it was very “punk.” It was, at best, “cool dad.”

A lot of that sort of behavior had come across as charmingly eccentric or radically open when Beto ran for Senate, but it was now given more serious scrutiny, and it didn’t always hold up well. This was unfair, O’Rourke’s many die-hard supporters argued: their candidate was being crucified by a cynical and unfeeling press. But even if they had a point, they were missing the big picture. O’Rourke was in a position to run partly because of the extraordinarily benevolent national media attention he received in 2018. Hardly any profile of him during that golden span could be written without deploying the word “Kennedyesque” or referencing his punk-rock past. It was only fair that a man who had once been gifted a tremendous tailwind now had to lean into the gale.

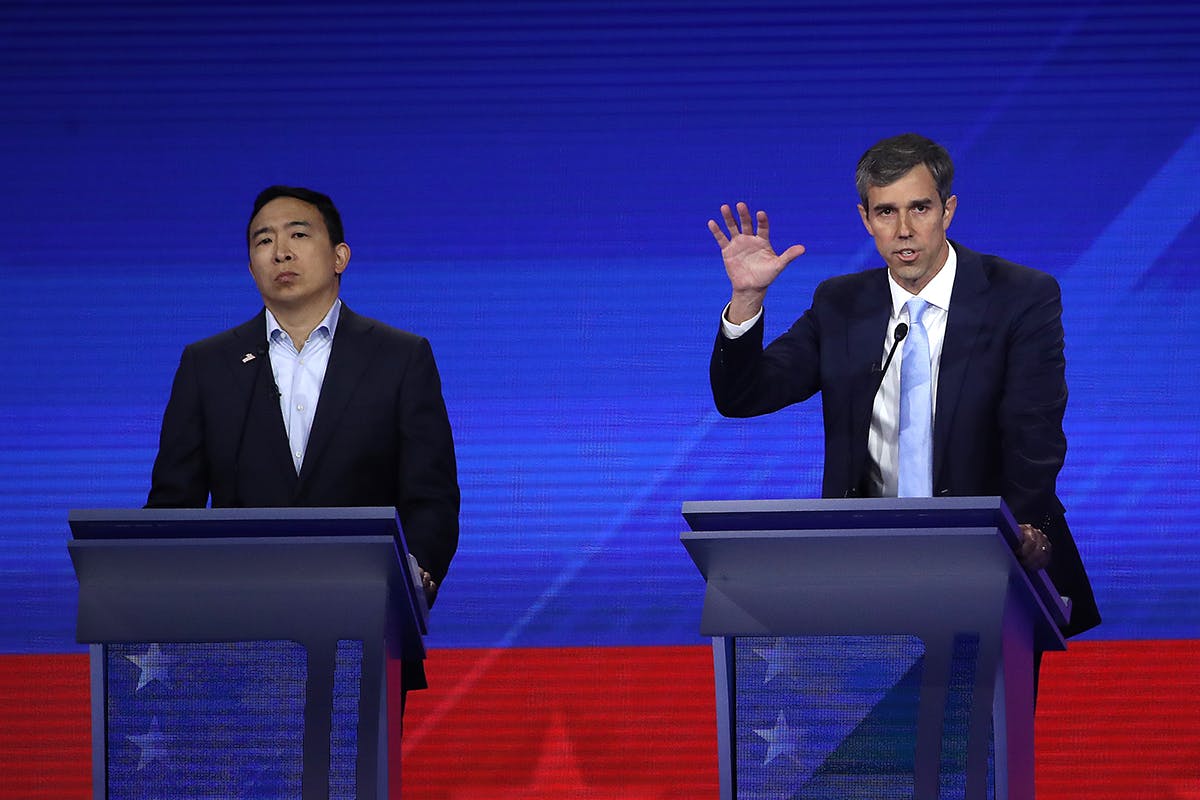

And lean he did—to the left. As his poll numbers suffered, down through the high, mid-, and low single digits, O’Rourke tried to recapture the Democratic electorate’s attention by staking out loud positions on controversial issues. In 2018 he told Texans that if they liked their AR-15s, they could keep them; in 2019 he suddenly announced that he wanted to seize them, a position that freaked out Democrats and gun control advocates, who felt it was counterproductive. (The only people who truly seemed to like it were America’s meatheads, who spent the next month posturing on social media about what they would do when Beto’s storm troopers came for their arsenals.)

In October he announced he’d be in favor of yanking tax-exempt status from churches that discriminated against gay people, a constitutionally dubious proposition that was momentarily noticed by a national audience but set the evangelical world on fire for weeks. Like Cortés sinking his ships upon setting foot in the New World, O’Rourke seemed to sever the possibility that he could run in Texas again by going full pinko.

The change of heart on guns was partly motivated by the twin massacres in El Paso and Midland-Odessa in August. The terrible crimes in O’Rourke’s backyard inspired real anger from him, perhaps the strongest moment of his run, and prompted him to revamp his campaign, in hopes of giving it the focus that it had lacked.

But looked at another way, the two shootings posed the question of why O’Rourke had left the state at all. One must tend to one’s own garden, as Voltaire’s Candide concluded. In 2018 Texas became O’Rourke’s garden, the place to which he was suited and the place that had lifted him up. He had put in a lot of work to make it so, and then he left it behind for Oprah Winfrey and the godforsaken wastes of New Hampshire.

O’Rourke’s decision to reach for the White House left the Democratic party without a strong contender to face Senator John Cornyn this year in a very important—and arguably winnable—election. That was his choice to make, but it was, at its core, a choice driven not by a commitment to public service but by ambition, whatever disguise that ambition chose to wear (as it always does).

To his credit, O’Rourke finally recognized, even before the first primary, that he was kaput and summoned up the dignity to call it quits. That put him head and shoulders above some of the other marginal presidential candidates who have clung on despite ample evidence that they’re not going to make the cut. Maybe it was a savvy move too—as the Democratic primary drags on endlessly and its many misfits snipe at each other, perhaps people will even come to miss the man. Maybe he’ll eventually be tapped to run as vice president.

Maybe. More likely, now that the spell has broken, his supporters will scratch their heads and wonder why they put so much faith in the toothsome skateboarder from West Texas in the first place. Did they really love him all that much, or did they just dislike Ted Cruz more than they could bear? It’s the sort of question no politician wants people asking about them. Which is why, for starting the year with one of the best brands in politics and ending it with a nationwide recall, Beto O’Rourke has earned a half-share of our Bum Steer of the Year Award.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Bum Steers

- Beto O'Rourke

- El Paso