“Let’s do a Dr. Ruth spoof,” says Herb Kelleher, jumping to his feet in a spasm of creativity. Kelleher is brainstorming with three of his top managers in his cluttered Southwest Airlines office near Dallas’ Love Field. The task at hand is to come up with skit ideas for an airline-industry conference. Kelleher envisions a scene in which Dr. Ruth would be on the telephone talking to Robert Crandall, the abrasive head of Dallas-based American Airlines, which has just become the largest domestic carrier. “Remember. Bob,” Kelleher says, mimicking the tiny sex doctor, “size isn’t everything.”

The focus shifts to New York deal-maker Donald Trump and his attempt to purchase the Eastern Airlines Shuttle, which runs between Boston, New York, and Washington. Someone suggests a musical parody: “The Lady is a Trump.” Then Kelleher lights on the battle for the entertainment-park business. Kelleher’s own Southwest Airlines could be creative fodder for this one; in 1988 it became the official airline of Sea World. Delta has Disneyland and Disney World. Kelleher suggests taking a poke at United, which not only does not have an affiliation but also just lost its place as the largest airline. “Why not make United the official airline of Popeyes fried chicken?” he suggests.

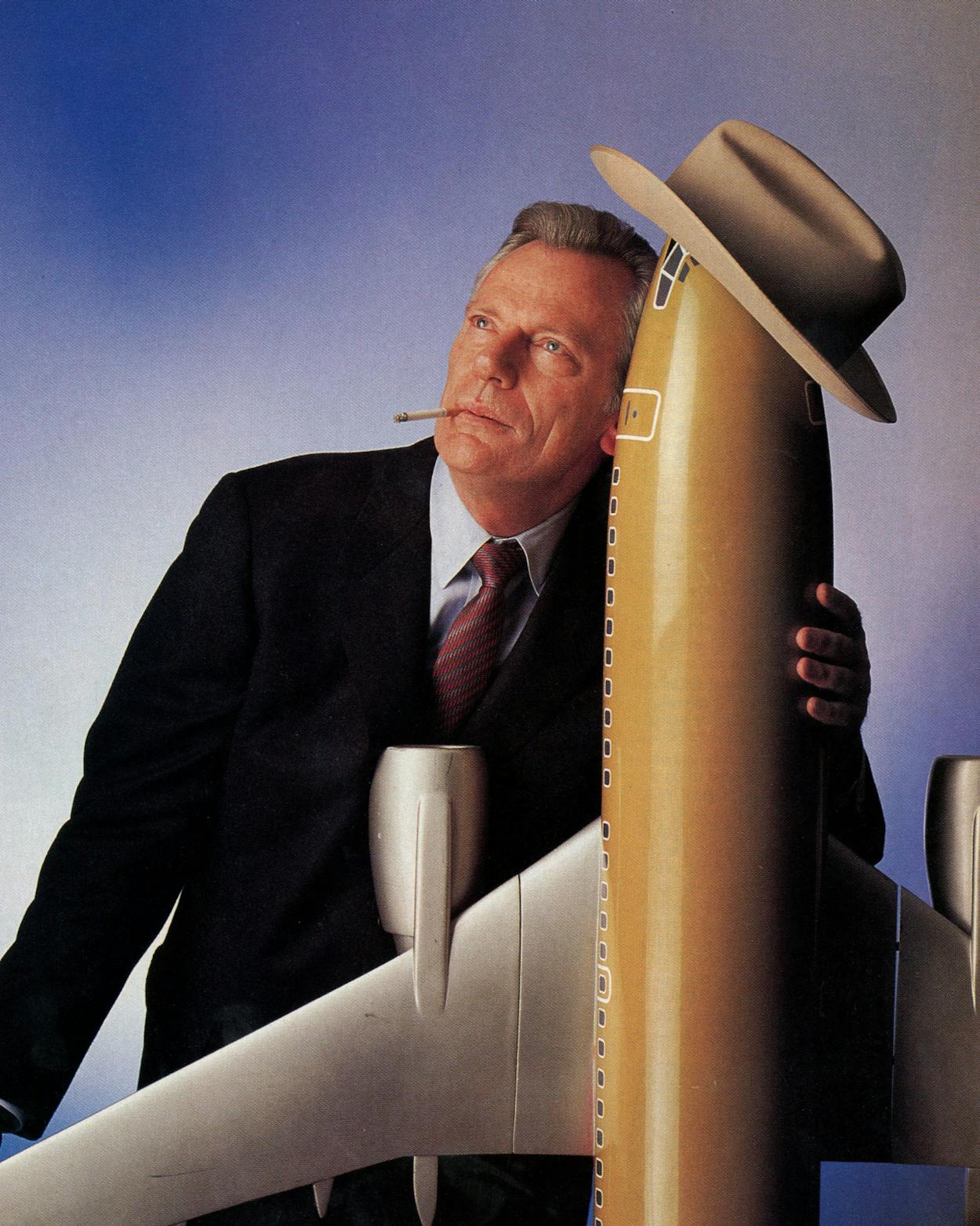

The meeting epitomizes the Kelleher personality: his irreverence, his spontaneity, his zaniness, and, most of all, his competitiveness. The airline he helped found and now runs is a direct extension of that personality—Kelleher himself often stars in the company’s offbeat commercials. In an industry beset by turmoil and takeovers, Southwest thrives by making its own rules.

At 57, Kelleher looks and acts like a first-generation astronaut, a hard-driving, hard-drinking, fast-living sort of guy whose swept-back hair frames a prominent widow’s peak and madcap blue eyes. His office is filled with small porcelain statues of wild turkeys, a tribute to his drink of choice. He smokes five packs of cigarettes a day, rarely drawing a clean breath of air, but so far he is in proud and happy defiance of the laws of health.

To understand that the man and his airline are one, all you need to do is get aboard one of his planes. You know the shtick. It’s seven-thirty in the morning. You’re sleepy. Your stomach is in knots. You’re under pressure. You just want to drink your coffee, read your memos, and get to your meeting. Then it starts: the Southwest Experience. The big-haired flight attendants all look like they went to the same West Texas high school. They are dressed in everything from baggy shorts and wild-print shirts to reindeer outfits. They give you safety information in rap, sing Christmas carols, or tell you the wrong time on purpose. Anything for a laugh. You bury your head in work. They’re not going to get you this time. You wish they would cut it out. “As soon as y’all set both cheeks on your seats, we can get this old bird moving,” comes the microphonic twang from the front of the airplane. There may be no food, no closets, no leg space, but at seven-thirty in the morning, you’re belted in your seat, laughing like a perfect fool.

Since June 18, 1971, when Southwest made its first flight from Dallas to San Antonio with ten paying customers, Texas has never been the same. By making flying around Texas easier than driving, Southwest immediately achieved the impossible—it separated Texans from their cars. Its virtual monopoly of the Texas commuter market has made it a modern-day cattle drive, the primary means of getting our goods—that is, ourselves—to market.

Southwest has radically altered our psychic landscape. The distance between any two of the ten major cities in Texas linked by Southwest is roughly 55 minutes. You can leave Harlingen or Dallas on a morning flight and do a deal in Houston over breakfast. Kelleher is living proof that the airline has made commuter marriages possible: he lives in Dallas, his wife, Joan, lives in San Antonio, and they see each other on weekends via Southwest.

Years ago Southwest issued bumper stickers that said: “Fly Southwest. Herb Needs the Money.” It worked; Southwest has made Kelleher—who is the president, the chairman of the board, and the chief financial officer—a rich man. In salary alone he makes almost $400,000 a year, and he is Southwest’s largest individual shareholder, owning 441,465 shares worth roughly $5 million. Today Southwest is the eleventh-largest airline in the country and one of the strongest carriers in the nation. In 1988, with Texas still in a slump and the airline industry in upheaval, Southwest made $57 million in profits, its best year ever, and it reported $860.4 million in revenues. Kelleher predicts that by 1990 Southwest will top $1 billion, the industry’s own benchmark of a major carrier. (By comparison, American’s revenues last year were $8.5 billion.)

Still, Kelleher clings to an underdog mentality. Before his first plane got off the ground, Kelleher spent three years in bruising legal warfare with Braniff and Texas International for the very right to fly. Southwest now serves 27 cities, 16 of them outside of Texas, and in 1988 Southwest carried 14 million passengers with a fleet of 85 jets. According to airline-industry calculations, passenger traffic as a whole expanded by 4 percent last year; Southwest grew by 16 percent. Kelleher the competitor is always looking for new conquests. His plan is to have the airline double in size—in revenues and number of planes—by the mid-nineties.

It is success achieved the Kelleher way—by being an iconoclast and going it alone. Southwest doesn’t lure us with gourmet meals, leather seats, or free newspapers. It treats us like cattle, but it gets us where we have to go, when we have to go, and usually on time. (After all, who needs food or comfort when we’re having so much fun?) Southwest had an easy time adjusting to deregulation, which sent the rest of the industry reeling in 1978. Because Southwest started out operating only within state borders, it has always existed in a deregulated environment. As a result, Kelleher’s mantra is: simple and fast. Southwest is the only airline in the country that won’t make connections with other airlines. Nor are Southwest’s flights part of travel agents’ computerized reservation system; Kelleher refuses to pay the fee for the privilege. Southwest’s tickets look like grocery receipts, which makes them far cheaper than the multipage tickets issued by other airlines. And Southwest was the first in the industry to sell tickets through automated teller machines.

There’s more. A few years ago Kelleher ordered the closets removed from the front of the planes because he noticed that departing passengers dawdled in front of them. When a cash crunch forced the sale of an airplane in 1972, pilots were ordered to fly the same schedule as before, but with three planes to cover the route instead of four. The only way to do that was to get the plane to the gate and back into the air within ten minutes. Today 85 percent of Southwest flights turn around within fifteen minutes; 30 percent accomplish it in ten. Moves such as those are why it costs Southwest 5.7 cents per passenger mile to operate the airline, the lowest in the industry, which in turn is why Kelleher is able to offer some of the lowest fares around.

Southwest sees its mission as different from that of other airlines. Most of them operate on a hub-and-spoke system. That means, for example, that if you want to go to New York from smaller spoke cities such as Austin or San Antonio, first you have to fly to the hub city of Dallas. Southwest flies from point to point, carving out its own market while avoiding direct competition with the majors. As Kelleher says, “We don’t fly to Dallas because we want to go to New York. We fly to Dallas and Houston because they are worthy destinations in and of themselves.”

“You’re crazy. Let’s do it.”

Among the mementos lining Herb Kelleher’s office—the toy cars and planes, the white shirt he wore on his first solo flight in a private plane—is a framed napkin with a triangle scribbled on it. At the top of the triangle is a dot that represents Dallas, on the left is one indicating San Antonio, to the right is Houston. This napkin is a facsimile of the napkin that businessman Rollin King drew on in 1966 when he came to Kelleher’s San Antonio law office to seek legal help with his charter-airplane business. King pitched the idea of starting an airline to connect Texas’ three largest cities. The reason Southwest Airlines exists is that Kelleher was a very bored San Antonio Lawyer. When King said, “Herb, let’s start an airline,” Kelleher replied, “Rollin, you’re crazy. Let’s do it.”

Or at least Kelleher said something like that. Herb often serves as his own Homer—he has a tendency to record and embellish legends even as he lives them. King recalls that when he drew the triangle, he knew his idea would work, but Kelleher was consumed with doubts about whether an intrastate airline would ever fly. Nonetheless, Kelleher was seized by the simplicity of the idea, put up $20,000 of his own money, and became counsel to the would-be enterprise.

Who is this man who took a crazy idea and transformed Texas? Kelleher was born on March 12, 1931, in Camden, New Jersey. He grew up in nearby Haddon Heights, a middle-class suburb of Philadelphia, where his father was a manager of the Campbell Soup Company. His mother, Ruth, was 38 years old when Herb was born and already had three older children, two boys and a girl. “I always assumed I was a slipup,” Kelleher says. When Herb was only 12, his father died of a heart attack. By the time he was an adolescent, one of his brothers had been killed in the war and his other siblings had moved away. Suddenly Herb was his mother’s only child, and like many successful men, he credits her as his strongest influence. “She never coddled me,” says Kelleher. “She always encouraged me to be independent.” He worked six summers at the Campbell Soup factory, and he played sports, both basketball and football, well into dark most evenings.

When Kelleher was eighteen years old, he played a basketball game that established his lifelong leadership style. He was the president of his class at Haddon Heights High and a well-known basketball star. On this particular night Kelleher had managed to score 29 points just before the end of the game and was within one shot of becoming Haddon Heights’ all-time scoring champion. There he stood in the center of the court, dribbling the ball aimlessly. The coach called time-out. “What’s the matter, Herb?” he demanded. Herb said he was refusing to shoot because he didn’t want to separate himself from the rest of the team. The next thing he knew, Herb was surrounded by teammates urging him to go for the shot. Herb wanted to be drafted by his peers for a place of preeminence. Once he was, he didn’t choke. He left the huddle, took the shot, and made the needed two points. At a crucial time in Southwest’s history, he would play out a corporate version of the game.

Herb went off to college at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, where he majored in philosophy and literature. Had he not agreed to go on a blind date with Joan Negley, a socially correct San Antonio girl who was attending Connecticut College, Herb might never have set foot in Texas. They met at a basketball game. “I had heard what a great basketball star he was,” says Joan, “but that night he sat on the bench the whole game. I think the coach let him play the last minute and a half.” After the game, they went out for hamburgers, and Joan had to pay the check. Herb had no money. He called her ”J.P.,” after the late financier J.P. Morgan, a nickname that stuck.

They were married in 1955 in San Antonio. Kelleher, eager to pursue a career that would give him financial independence, attended law school at New York University, where he made law review and graduated with honors in 1956. He clerked for the Supreme Court of New Jersey and then joined the largest law firm in the state. By then, he and Joan had two children and Kelleher was well on his way to becoming a successful corporate lawyer. On vacations they would come to San Antonio and to Joan’s family ranch near Big Bend. Slowly, Texas became part of Kelleher’s imagination. Joan never asked him to move to San Antonio for fear he would say yes and later feel he had been pressured. “One day I was walking in the snowy muck in Newark, and I thought to myself, ‘I could be in Texas,’” he says, explaining their 1961 move.

Joan has the languid, well-mannered demeanor of a woman who has known comfort and privilege all her life and feels no compulsion to flaunt it. Her family’s fortune is derived from ranching and insurance interests. It is entirely possible that the reason Joan never asked Herb to move to San Antonio is that she enjoyed being away from the society in which she was raised. Since her return, she has worked for various civic causes, such as historic preservation, but mainly she has raised her family.

Kelleher has had little time for the conventions of domesticity. “He changed a diaper one time and threw up,” says Joan. The couple have four children: Julie, 31, works with animals at Sea World; Michael, 29, has a retail software store; Ruth, 27, is a lawyer who works for the Texas Senate; and David, 25, is bartender at a San Antonio restaurant. The Kellehers’ marriage may have run according to fifties rules, but now has an eighties twist: He lives in a University Park townhouse in Dallas, and she lives in their home in Olmos Park. Neither of them regards their commuter marriage as strange. “I knew what kind of man I was marrying before I married him,” says Joan.

When Kelleher first arrived in San Antonio, Joan’s family moved quickly to get him established. Her stepfather, John Catto, a wealthy insurance broker, took him downtown to meet Wilbur Matthews, the starched sultan of the local legal community and the head of the firm of Matthews and Branscomb. Kelleher sat passively as the two men arranged for him to join Matthews’ firm. The subject of compensation never came up.

Kelleher had been in town less than a month before Alfred Negley, his brother-in-law, introduced him to John Connally, who was running for governor. Connally was sufficiently impressed to put Kelleher in charge of his gubernatorial campaign in northern Bexar County. Connally won the governor’s race in 1962 with a boost from Bexar County. Some people struggle for generations to become a part of the small power circle in San Antonio; Kelleher found himself a complete insider within less than a year.

Next he took his place at Wilbur Matthews’ law frim, which at the time operated at a genteel pace that allowed for the serving of tea in the early afternoon. But Kelleher was constitutionally unsuited for a genteel way of life. He worked well into the night on complicated cases, always writing out his legal briefs on yellow pads in his flowing cursive. But he was chronically disorganized. One night the security guard walked into Kelleher’s office and mistook his mess for signs of a struggle. The guard telephoned police and reported a break-in. “Every day I went to work I felt my shoulders droop a little more,” Kelleher acknowledges.

Then Rollin King entered his life and scribbled the triangle on the napkin, and Kelleher was bored no more. Kelleher took King and his idea for Southwest Airlines with him when he left Matthews’ law firm in 1970 and joined Jesse Oppenheimer and Stanley Rosenberg—two other restless San Antonio lawyers—to form a new firm.

If King was the father of Southwest Airlines, Kelleher was its midwife. His $20,000 made him a founding shareholder. He went to the same men who had given money to Connally’s campaign—John Peace, Robert Strauss, Dolph Briscoe, Curtis Vaughan, and other power brokers—and raised the first $543,000.

On November 27, 1967, Kelleher filed an application with the Texas Aeronautics Commission to launch Southwest Airlines with flights between Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. The application was approved unanimously, and then the war began. Braniff and Trans-Texas (the forerunner of Frank Lorenzo’s Texas International) challenged the commission’s decision in an Austin district court. At issue was whether Texas travelers were adequately served by existing airlines. The next three years of Kelleher’s life were absorbed in legal battles that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. But Kelleher’s future competitors weren’t content to fight it out in court. Kelleher later showed that executives of Texas International, in a move designed to scare off Southwest investors, had filed numerous complaints against Southwest with the Civil Aeronautics Board. It is hard to imagine what the complaints were in reference to since Southwest had no pilots, planes, or passengers at the time.

“I have often said that if Braniff and Texas International had left us alone and not been so rotten and dirty and tried to sabotage us every step of the way, Southwest Airlines would not be in business today,” says Kelleher. “They were too stupid to realize the psychology of the situation. The more dirty tricks they played, the more resolved I became to beat them.”

But by the summer of 1969 almost everyone but Kelleher was losing resolve. Southwest’s board of directors was ready to give up. The original $543,000 was gone, most of it to legal battles, two of which Kelleher had lost. But he believed he could win on appeal and desperately wanted the chance. Kelleher made an offer to the board: if they would keep going, they wouldn’t have to pay him unless he ultimately won. They accepted his challenge. Kelleher worked like a demon, once going 48 hours straight to prepare for a hearing, then leaving the court to go to a cocktail party to raise money for Southwest. Finally, in December 1970 his gamble paid off. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal by Braniff and Texas International of a case that Kelleher had won before the Texas Supreme Court. Southwest was ready to take off. It had $143 in the bank and $100,000 in past-due bills—most of it owed to Kelleher.

Mr. Inside

For the next few years Kelleher was made Mr. Inside at Southwest Airlines. He was the company’s lawyer, spending his time negotiating contracts with Boeing for the purchase of airplanes, writing stock offerings, and raising money. He also served as a mediator between Rollin King, who became the chief operations officer, and Lamar Muse, a flamboyant airline veteran who came to work as Southwest’s president. King and Muse both had strong, usually conflicting views about what was best for Southwest Airlines; the result was a protracted power struggle.

Early on, Muse tried unsuccessfully to remove King from the board. Then, over the objections of the board, Muse made his son, Michael, an officer of the company. Kelleher tried to make peace between Muse and King but to no avail. In 1978 Muse made another power play. He went to the board and said that either King went or he went. King stayed and the board voted to accept Muse’s resignation. Kelleher was torn between both men and abstained from the vote.

King thought he would be named as the new president, but the board instead turned to Kelleher. “I was surprised,” says Kelleher. “It was not something I sought, but there I was—one minute Lamar was in charge, and the next minute I was.” King remains a member of the board. Just as at the Haddon Heights basketball game, Kelleher was drafted to lead his peers.

His relationship with Muse took a Shakespearean turn in 1981, when Kelleher—who by then was so totally in command of Southwest Airlines that employees were calling him Southwest’s Father, Son, and Holy Ghost—found himself in an all-out war with his old friend. Bitter over being kicked out of Southwest, Michael Muse had raised enough money to start a yuppie version of Southwest—Muse Air. He started competing with Southwest in Texas, California, and Florida with sleek blue-and-white airplanes, meal service, assigned seats, and non-smoking flights. Employees at Southwest had a nickname for Muse Air. They called it “Revenge Air.”

But Michael Muse couldn’t crack Southwest’s hold, and by 1984 Muse Air was practically bankrupt. Lamar took over the operation and put Muse Air up for sale. Kelleher was fearful that Frank Lorenzo would buy it and use Muse Air’s gate positions at Houston Hobby to go after Southwest.

One day Kelleher telephoned Lamar Muse and suggested a meeting. When Muse walked through the door of Kelleher’s townhouse, Kelleher asked, “Lamar, are you more interested in running an airline or going fishing in Vancouver?” Lamar told him he’d rather go fishing. Two hours later, Kelleher had agreed to buy Muse Air. The price came to $76 million.

Not only did Kelleher knock out Muse Air, but when it was over, Herb, not Michael, had emerged as Lamar’s good corporate son. Michael never forgave his father for selling his airline, and even now Michael refuses to speak to him. But Kelleher and Lamar Muse remain friends. “Herb and I have raised a lot of hell together,” Muse told me. “He’s the best friend anyone ever had and the toughest competitor on earth.”

Corporate Culture

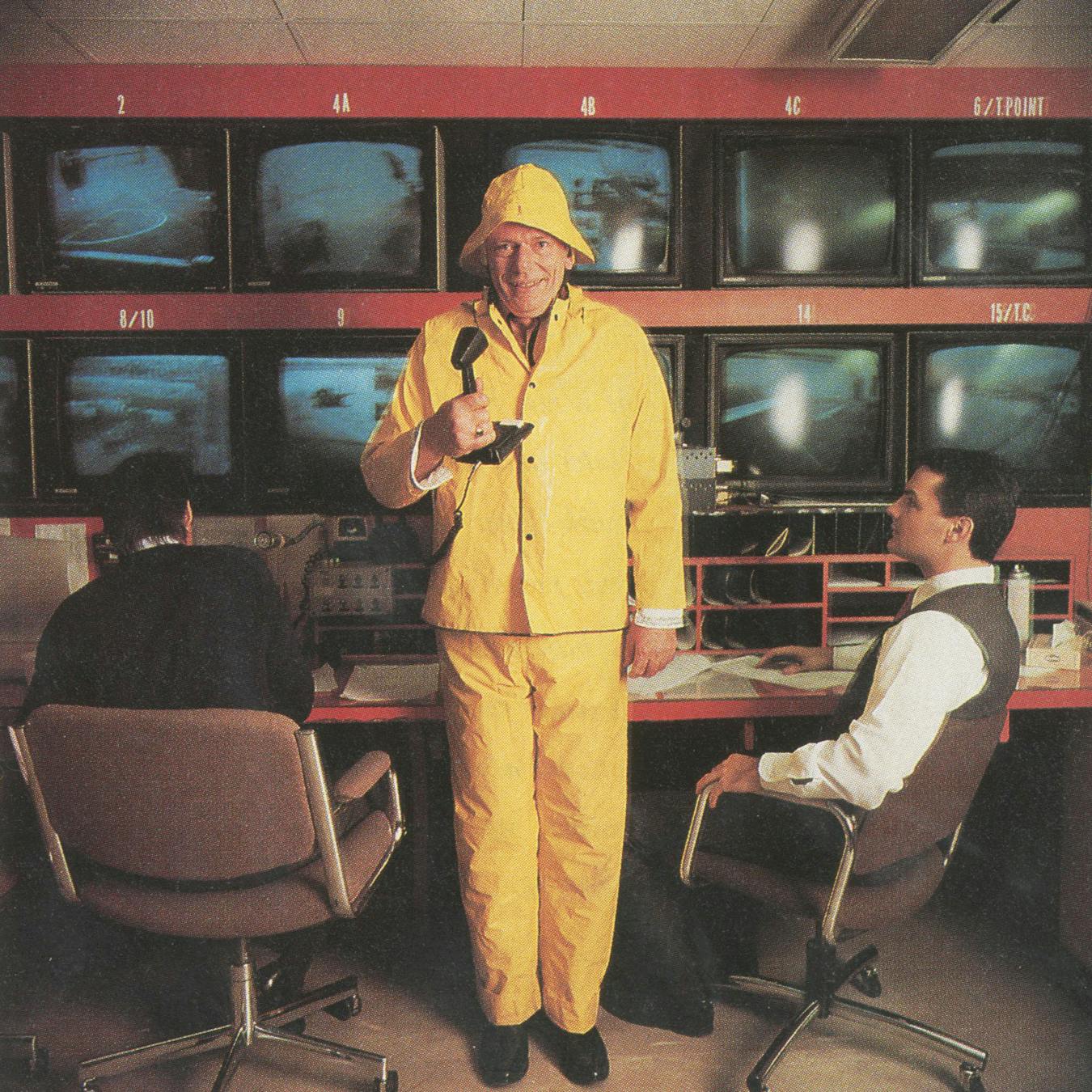

At Easter the head of the eleventh-largest airline in the country has been known to fly as the Easter Bunny. On St. Patrick’s Day Kelleher has flown as a leprechaun. On this day he is traveling as just his zany self. “I just love these three-hundreds,” Kelleher is saying as we make our way to the rear of the Boeing 737-300, which seats 137 customers, 15 more than the 737-200. Most of the passengers instantly recognize Kelleher from the company’s advertising campaigns. They remember the ad in which Herb is locked out of a Southwest plane because he talks too long about the airline’s on-time record. As he distributes peanuts on the flight from Dallas to Houston, the passengers respond to Kelleher with an exuberance ordinarily reserved for old high school buddies. “Would you care for peanuts? I grow them in my basement,” Kelleher says to a beer-drinking businessman from Lubbock. “Herb,” says the businessman, “I gotta tell you. You’re the ugliest flight attendant I’ve ever laid eyes on.” The entire rear of the airplane finds the scene uproarious.

That kind of behavior is woven into the life of Southwest Airlines. More than being just a business, it approaches being a cult, with 6,500 employees for members. The employees own 10 percent of the airline, and ownership begets loyalty. Each new employee is shown the Southwest Shuffle videotape, which describes the workings of each department—from the baggage handlers to the pilots to the secretarial pool—in rap. (This one is sung by the mechanics: “When you need spare parts to put on the plane/We get the right ones/And we order it again.”) Every Friday at noon, the employees in Dallas gather in the parking lot at their headquarters for a cookout. Most companies this size frown on nepotism. Not Southwest. “We’ve got as many as six members of the same family working for us,” says Kelleher. “Why, some of our employees have been married to one employee, divorced, and married to two, maybe three others.” (Since the Michael Muse experience, though, there is an anti-nepotism rule among the company’s seventeen officers.) Kelleher’s list of employees is updated constantly, and he tries to know the names of all of them. They call him Herb or Herbie, but never Mr. Kelleher. On Black Wednesday—the day before Thanksgiving and traditionally the busiest day of the year for airlines—Herb works in the baggage department at Love Field, loading and unloading customer bags.

His management style is fiercely anti-hierarchical. Each week about two hundred letters arrive from passengers, and Kelleher or Colleen Barrett, the vice president for administration, reads every one of them. Barrett is Kelleher’s alter ego. Together, Herb and Colleen—as all the employees refer to them—run Southwest Airlines. If there’s a problem, Herb and Colleen pull together a group of employees and talk until a solution emerges.

Barrett, a friendly, no-nonsense woman of 43, has worked for Kelleher since 1968, when he was a lawyer in San Antonio and she became his secretary. Her first duty was to set up a filing system; Kelleher had ten years’ worth of cases piled on and around his desk. Barrett still performs some secretarial duties, though she is clearly an executive as well. Kelleher calls her his “beeper” because she does her best to move him from meeting to meeting. They unapologetic workaholics who put in jammed days and then go home to more work in neighboring townhouses. “Colleen gives me all the freedom and latitude of a prisoner in a North Korean prison camp,” he says.

All of the primary aspects of Kelleher’s personality—his obsessiveness, his slap-happiness, his combativeness—are not only present within the culture of Southwest Airlines, they are celebrated there. No one gets angry at Kelleher for being late, because no one expects him to be on time (which, however, does not hold true for his airplanes—

Southwest has one of the best on-time records in the industry). His daughter Ruth says her father takes pranks and games so seriously that one night they played a form of tag until 2 a.m. Finally, she fell into her bed exhausted and was in a hazy sleep when she felt her father lightly touch her big toe. “Gotcha,” he said, chuckling off to bed.

Kelleher’s daily schedule is crammed with duties that nurture the organization he has created. Every month he personally hands out Winning Spirit awards to employees who were selected by fellow workers for exemplary performance. In December he gathered thirteen award-winners in a conference room for the company ritual. There sat muscular Vincent Lujan, an Albuquerque ramp agent. While cleaning an airplane, Lujan found a purse containing $800 and several credit cards. He turned it over to his supervisor, who found the owner. That act of honesty won him companywide recognition. Lujan received two free airline tickets and a bear hug from Kelleher. Cindy Burgess, a Dallas flight attendant, earned the same treatment for befriending Kisha, an eighteen-month-old girl who was en route from Amarillo to Dallas for a kidney transplant. Since Kisha had been hospitalized in Dallas, Burgess had run errands for her parents, including washing and ironing their clothes. Kelleher’s voice swelled with emotion as he described how Burgess had hired a baby-sitter to look after her own two children so she could help Kisha. Kelleher was the head of the clan, gathering his favorite few. The more heartrending the story, the better he liked it.

Southwest’s culture is constantly being refined. The pressure to behave like other airlines is enormous; Kelleher fights it at all costs. In a monthly meeting with dispatchers, who supervise the routings of the airplanes, Kelleher says that he has received several letters from passengers who complain that when they call ahead, they receive inaccurate information about their flights. The dispatchers tell him that the solution is to invest in a computerized system at a cost of $100,000 per plane that would give dispatchers up-to-the-minute flight information. It is standard at major carriers. Kelleher thinks it’s not essential and therefore not worth the expense; he likes keeping Southwest low tech.

One of his basic premises is that Southwest must stay on the offensive At a senior-management group meeting, Kelleher hears a disturbing report: If a proposed new noise rule goes into effect in San Diego, Southwest won’t be able to comply. He turns stern and serious. “I’m willing to sue,“ he tells his managers. “The carriers who aren’t opposing it are doing a real disservice. This is the kind of thing that spreads and makes it impossible to do business. Sue ’em.”

The only time Kelleher has run into trouble was when he purchased Muse Air, which he renamed TranStar. The competitive side of him wanted TranStar, and it made good sense for him to block Lorenzo from purchasing it. But TranStar offered meals long-haul routes, and connections with other airlines. It stood in perfect juxtaposition to Southwest. He tried to sole the problem by running the two airlines as totally separate operations, but external and internal pressures proved to be too great.

Externally, he was in a fare war with Lorenzo, who slashed one-way fares between Los Angeles and Houston to $79 to keep TranStar from making inroads at Hobby. Internally, employees from TranStar and Southwest were at odds. Nowhere was the acrimony more apparent than among the pilots. Southwest pilots believed that their job security was threatened by TranStar’s lower wages.

One day, Kelleher faced the Southwest pilots across the bargaining table. He could not understand why they were worried. But the pilots viewed the $76 million he had spent to purchase Muse Air as money that could have upgraded Southwest’s fleet and the pay scales of Southwest’s pilots. To protect their own seniority, the Southwest pilot’s union wanted to represent the Muse Air pilots. When Kelleher insisted on keeping the two work forces separate, one of the pilots looked Kelleher in the eye and said, “This is just the low-down, cutthroat kind of thing Frank Lorenzo would do to his employees.” Kelleher’s image of himself was violated. He flew into a rage and broke off negotiations for weeks. The agreement they eventually reached was rejected by TranStar pilots because it put them near the bottom of Southwest’s seniority system and offered limited job security. When Kelleher refused to negotiate directly with the TranStar pilots, a few even put bumper stickers on their cars that said: “Will Rogers never met Herb Kelleher.”

On August 9, 1987, Kelleher implicitly declared defeat. He closed down TranStar and sold many of the airplanes to Lorenzo. The TranStar experience was a costly one. That year Southwest made only $20 million, a 60 percent drop from 1986. Even more than being a financial drain, the purchase was an egregious example of Kelleher going against his own strengths and the philosophy of the airline. But wallowing in what went wrong is not part of Southwest’s culture. Even now Kelleher prefers to see it as a good try, not a mistake. “If things had turned out differently,” he says, “we would have had a hell of a foothold on the long-haul market out of Hobby.

Keep Moving

In late 1978 Kelleher called a meeting of his senior officers and told them Southwest Airlines could not just settle back and rely on Texas business commuters as a cash cow. Like a jet plane, Herb Kelleher and his airline need to keep moving. “We had run our string in Texas. Our growth was stymied,” Kelleher recalls. Indeed, Southwest was too dependent on the Texas economy. At one time 50 percent of the airline’s revenues flowed from the Dallas-Houston route. Southwest needed to diversify geographically. The senior officers were reluctant to venture too far out of Texas. “It was almost a mystical thing,” explains Kelleher. “It’s like we were scared of the outside world.” But Kelleher’s fears were exactly the opposite—he didn’t want to be fenced in. Of course, Kelleher prevailed. Southwest started service to New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, San Francisco, St. Louis, Chicago, and Detroit. Given the drop in oil prices and real estate values, it’s a good thing Kelleher did not sit back and count on Texans to provide him with a sinecure. Today just 4 to 6 percent of the airline’s revenues are derived from Dallas-Houston travelers.

Part of Southwest’s problem was that it could not expand from its base at Love Field. In early 1979 then House majority leader Jim Wright of Fort Worth, in an effort to protect the hub status of DFW airport, tried to ban all interstate traffic out of Love Field. Kelleher flew to Washington for a three-month battle, mustering all of his political skills and personal connections to fight one of the most powerful men in Washington. Kelleher quickly ceded Wright the House side and concentrated his efforts on the Senate, where an old buddy from law school, Oregon senator Bob Packwood, tied up every piece of aviation legislation until Wright agreed to compromise. The compromise, known as the Wright Amendment, gives Southwest the right to fly out of Love Field to the four states bordering Texas.

What the Wright Amendment means is that Southwest passengers can’t fly straight from Love Field to Los Angeles; they have to buy a ticket for each leg of the journey. Moreover, their bags can’t fly direct either but must be removed from the airplane and reloaded at every hop. The amendment even prohibits Southwest from advertising its Los Angeles flights in the Dallas area.

Financial analysts and the big carriers regard the Wright Amendment as a boon to Southwest since it is the lone carrier out of Love. Kelleher doesn’t. “If other carriers think it’s so great, let them come into Love and live with it,” he says. Why doesn’t he do what he’s good at—challenge the amendment in court? “Because I told Jim Wright I wouldn’t when I sat down in his office and we wrote the compromise,” he says.

Unable to expand any further out of Love Field, Kelleher began looking for a new base of expansion and settled on Phoenix. Since 1984, Kelleher has doubled Southwest’s daily departures from Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, and he is now in a head-to-head battle with America West, which is based in Phoenix and has the largest share of the market. Southwest operates out of dingy forty-year-old Terminal One, so old fashioned that passengers have to walk outside to go from one gate to another. Far from being ashamed of the facility, Kelleher launched an ad campaign, bragging that Terminal One is more convenient to parking areas. Meanwhile, America West holds forth in modern, fortresslike Terminal Three. Southwest won’t remain in Terminal One forever. Over the strong objection of America West, Kelleher won an 8–0 victory before the Phoenix City Council in December for access to sixteen gates at the airport’s fourth terminal, which will be completed in 1990. By then, Kelleher expects Phoenix to be Southwest’s busiest city.

Last November Kelleher went on an all-out raid in the Phoenix area by slashing fares and aggressively advertising Southwest’s on-time record. America West’s chief executive, Ed Beauvais, matched Kelleher fare cut for fare cut. Now both airlines are offering $19 one-way tickets from Phoenix to Los Angeles, San Diego, and Las Vegas. Some analysts believe that Kelleher may be not just after the Phoenix market but out to take over America West as well. Beauvais expanded rapidly, and in 1987 showed a loss of $45.7 million, but he quickly moved to cut flights and personnel and is managing to hang on.

Kelleher’s heaviest artillery in Phoenix is the same as it is in Texas—his personality. Recently he appeared on Phoenix television stations with a brown-paper bag over his head. He was identified as the Unknown Flyer. The thirty-second ad was in response to America West’s charge that Southwest passengers are embarrassed to fly such a no-frills airline with “plain” planes. “If you’re embarrassed to fly the airline with the most convenient schedules to the cities it serves, Southwest will give you this bag,” says the Unknown Flyer. He then offers the bag to the passengers who are embarrassed to fly the airline with the fewest customer complaints in the country. Kelleher then lifts the bag from his head and offers to give the bag to anyone who flies Southwest “for all the money you’ll save flying with us.” The final scene shows Kelleher in a shower of money, grinning at the camera.

Such antics are a regular part of his day. When Kelleher painted one of his 737-300’s to look like Sea World’s killer whale and christened the airplane Shamu One, he got a telephone call from American Airlines’ Crandall, who congratulated him for the marketing gimmick. “Just one question,” asked Crandall. “What are you going to do with all the whale shit?” In a nanosecond Kelleher replied, “I’m going to turn it into chocolate mousse and spoon-feed it to Yankees from Rhode Island.” The following Monday, Crandall, a Yankee from Rhode Island, received a large tub filled with chocolate mousse with a Shamu spoon stuck poetically in the center.

Like Shamu, the company icon, Kelleher may be a showboat, but his basic instincts are those of a killer. The lesson of the Phoenix war is that in the era of deregulation, it’s attack or perish. Competition and mergers have wiped out the smaller, weaker airlines. The moment America West showed a loss, it became a target for acquisition. Kelleher believes the reason no airline has tried to take over Southwest is its strong balance sheet. Says Kelleher in killer-whale fashion, “The way to avoid a takeover is to keep moving and stay strong.”

Kelleher says he feels like he’s been in the Twilight Zone: Before deregulation in 1978, the top ten carriers transported 90 percent of all passengers; in the ten years after deregulation, the same thing is still true. Nonetheless, Kelleher is still an advocate of deregulation. It was Southwest’s early record of low fares and getting high investment returns that helped convince the U.S. Congress that deregulation of the industry would benefit passengers. But deep fare cuts that are endemic to airline warfare make shareholders nervous. One evening he was complaining about the fare wars over dinner with his daughter Ruth, who looked at him and said, “Stop whining, Dad. You started this.”

Kelleher believes that what needs revamping are the facilities that make air travel possible. Since deregulation, traffic has nearly doubled, from 243 million passengers annually to 468 million, but a major airport hasn’t been built since DFW, fifteen years ago. Now he’s lobbying Congress to build more airports, runways, and traffic-control systems. The main reason Kelleher is not expanding to the East Coast is that air traffic is too congested; he can’t turn his planes around fast enough.

Of course, the question not only for Southwest stockholders but for Texas travelers is, What’s next for Herb Kelleher? Once, Kelleher fancied a career in politics; when he lived in San Antonio, he gave serious consideration to running for the Texas Senate. Lamar Muse believes to this day that Kelleher will succeed Lloyd Bentsen in the U.S. Senate. “Herb is, by nature, a political animal,” Muse says. In pursuing the primary goal of the airline business—shareholder profits—Kelleher has also used the airline to engage in the larger pleasures of war and politics.

Besides, since Southwest Airlines is an extension of Kelleher, he is not prepared to imagine it without him. “The history of Southwest Airlines is still unfolding,” says Kelleher. “I’m not finished yet.” The board of directors is concerned that a man who smokes five packs of cigarettes a day has not identified a clear successor. Employees wander the halls of the headquarters, wondering what would happen to them and their airline if Kelleher dropped dead of a heart attack. When Roy Spence, the president of Austin-based GSD&M, Southwest’s advertising agency, was asked what would happen to the airline if Herb died today, Spence became slack-jawed. He took a few seconds to think about it and then said, with a straight face, “Herb ain’t never going to die.”

Certainly he shows no signs of slowing down. During a rollicking Christmas office party, a group of employees performed their own parody of the “Twelve Days of Christmas,” satirizing various aspects of life at Southwest Airlines. “On the first day of Christmas Herbie gave to me a Jaguar and a big raise,” sang the employees. Kelleher sat at the front table, happily presiding over the pandemonium. His mood improved with each passing verse, as employees petitioned him for no more mistagged bags, no more frequent-flier double credits, no more Fun Fares, and every Friday off. When he rose to respond, Kelleher congratulated them with a revealing remark. “My worst fear,” he told them, “is that one day Southwest Airlines will grow old and stuffy.”