This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It has been a long and not very happy eight years for the University of Texas Lady Longhorns and their coach, Jody Conradt, since they won the national basketball championship in 1986. They haven’t been back to the Final Four since 1987. Their twelve-year-long winning streak in Southwest Conference games ended in 1990. Their archrival, the Texas Tech Lady Raiders, replaced them as the dominant team in the conference and won the 1993 national championship. They have even been described, in the hometown Austin American-Statesman, as being “tagged with the lesbian label.” Now, on the afternoon of January 22, they had a chance to reestablish themselves. They were about to play the Lady Raiders, who were ranked fourth in the country and looking big and menacing in their black uniforms trimmed in red. More than 12,000 people had come out in a dispiriting drizzle that wrapped Austin in a sloppy haze to see if a young and unproven Lady Longhorn team could stop the downhill slide.

You could see that this was no ordinary game by looking at the area around the Lady Longhorn bench. Admiral Bob Inman sat in the guest coach’s chair, making his first public appearance since withdrawing as President Bill Clinton’s nominee for Secretary of Defense. Seated next to the bench were Governor Ann Richards and former congresswoman Barbara Jordan. Congressman Jake Pickle was there too, and so were the UT chancellor, president, and regents chairman. Suddenly the lights went out in the windowless arena known on campus as the Super Drum, rock music throbbed, and the Lady Longhorns sprinted out to center court through spotlights and a nebula of machine-induced smoke.

The game was a showcase for everything women’s athletics is supposed to stand for—athletic skill, good coaching, and healthy, fair rivalry. What most people in the stands did not realize was that the game also represented all of the problems facing women’s sports today. Intercollegiate athletics for women is in danger of going the way of intercollegiate athletics for men, where the things that happen away from the game are tainting the game itself. For men, the problems are poor grades, cheating in recruiting, and the use of performance-enhancing drugs. For women, the problems are issues that are all too familiar, not just in sports but in life. These are issues of gender and sexuality—issues that divide women from men, such as equality; and issues that divide women from other women, such as lesbianism.

The two teams on the basketball court knew all about these problems. The University of Texas has had the best women’s athletic program in the country for the past twenty years, but that didn’t prevent a group of women students from suing UT because UT women don’t have the same opportunity to participate in athletics as men. A similar complaint has been lodged against Texas Tech. As a result of the legal actions, and others like them across the state and nation, animosity between men and women involved in college athletics is at an all-time high. Men fear that their budgets will be cut in order to give parity to women’s sports.

And then there is the issue of lesbianism in women’s athletics. It was brought into the open last summer by the American-Statesman in a three-part series on homosexuality in sports. The third part focused on the women’s athletic department at UT. The article quoted a former Lady Longhorn who had left the program as recalling that when she originally signed with Texas, “People were saying, ‘They’re a bunch of dykes up there.’ ” Such allegations have made recruiting difficult because they have been used successfully by other universities to prevent sought-after players from attending UT. The most notable loss was onetime UT recruit Sheryl Swoopes, an all-American and NCAA Player of the Year who led Tech’s charge to the national championship last spring. Swoopes, the article claimed, had left UT just days after she arrived there as a freshman because there were lesbians on the basketball team. Jody Conradt smoothed over speculation about Swoopes’s much-debated defection by saying, “That must be reason number five hundred and forty, at least,” and Swoopes herself has cited homesickness as the reason for her departure. Conradt stood up for what she called “diversity,” assiduously avoiding the term “lesbian”: “The best team I ever had had diversity,” she said. “When our society learns to embrace diversity, we’ll be a lot better society.” But an unidentified administrator in the men’s athletic department told the Statesman, “It’s about time you nailed them.”

The focus of the American-Statesman articles was on the University of Texas. The articles left unspoken the extent to which the lesbian issue permeates women’s sports and involves not only players but coaches. Privately, prominent figures in women’s athletics acknowledge that there are lesbian players or coaches in every major women’s program, a fact that prompts no end of rumors and speculation. A person’s sexual orientation is a private matter. But sports is a public activity, and women’s athletic programs are fighting not only for respectability and equality but also for more public attention. Men’s athletics is used to public scrutiny; that is why, when controversy involving coaches erupts—names like Barry Switzer at Oklahoma, Jackie Sherrill at Texas A&M, and Bobby Collins at Southern Methodist come to mind—the coach frequently loses his job. With female coaches of women’s teams, the matter of coaches’ conduct is burdened with issues of sexuality. Politics, morality, and the right to privacy muddy the distinction between right and wrong. And there will always be the argument that women coaches and players are unfairly subjected to a higher standard than their male counterparts.

This is a time of growing pains for women and women’s sports, a time when women are wresting themselves away from the old stereotypes that women athletes aren’t real women and women’s sports aren’t real sports. Yet so intense is their fight against the stereotype, it is almost self-defeating. Somehow the sad fact for females in sports has always been—and still remains—not what kind of athletes they are but what kind of girls they are.

Last October, half a year after leading the Texas Tech Lady Raiders to the national championship, Sheryl Swoopes went to New York to receive the Woman of the Year award from the Women’s Sports Foundation. Swoopes had grown up not far from Lubbock, as had all but one of the players on Tech’s championship team. She was a testament to Tech coach Marsha Sharp’s recruiting message that the right kind of girls make the right kind of players. After Swoopes left UT, she went home to Brownfield, hid at her mother’s home to avoid having to talk to a frantic Lady Longhorn assistant coach, and eventually ended up at Texas Tech.

Marsha Sharp is careful never to mention the L word when discussing the kinds of players she wants. “We want to keep the best talent at home,” she says. “We have felt all along that that was the key. One of the goals of our program was that the nucleus was going to be West Texas—fundamentally sound kids we’d be comfortable coaching and also have a big fan base from the small communities. We feel strongly about it.”

Sharp didn’t come by her recruiting philosophy by accident. Her good-girl gospel was the philosophy espoused by Dean Weese, the godfather of West Texas girls’ basketball and Sharp’s mentor at Wayland Baptist University in Plainview, fifty miles north of Lubbock. “Dean was a major influence for the girls’ game,” says Sharp, who hired Weese’s brother Linden as her assistant. “It’s impossible to know how many girls now shoot the ball from the set position the same way.” The Dean Weese style of shooting is called the Panhandle Push—with the ball set in the girl’s hand, knees bent deep, and then a flip of the wrist that propels the ball right into the basket. “Dean was whipping everybody with it,” says Sharp, who still uses the style at Tech. “We used to tape a tongue depressor on the back of our shooting hand to prevent us from bending the wrist backward when we pushed the ball off.”

Today Dean Weese, 58, is the director of girls’ athletics and coach of the girls’ basketball team at Levelland High School, thirty miles west of Lubbock. Outside of town, signs welcome you to various churches and tout the Levelland Lobos football team. But one proudly boasts “This Is Dean Weese Country.” In the gym the Levelland Loboettes, in their red shorts, black tops, and black high-top shoes, are practicing jump shots, one-dribble lay-ups, and free throws. They wend up and down the court in a figure-eight drill for ten minutes. Weese keeps an eye on the young women from the bleachers and while prowling along the sidelines. They seem almost fragile. Weese gives his varsity team gold jerseys and pits them against the black-topped B and C teams. In gold, the girls look like a swarm of yellow jackets overpowering their defenseless opponents. “Don’t just stand there!” he shouts at the B and C team players. “They’ll beat your brains out every day. You need to pay attention and not get beat so badly—y’all are bigger than they are!”

But size has never really been an issue with Weese’s teams, and his creed of winning has never changed. It is a curious mix of mind over matter and social snobbery that would be unacceptable in the boys’ game. “If you let me come to a high school and pick the fifteen girls with the best grades and the best looks, they’ll win,” says Weese. “Everybody’s got a certain amount of athletic ability. Girls’ coaches don’t feel you have to have great, great talent to win. Our Levelland basketball team went to the state championship last year as the smallest team.” Jane Goheen, who coaches basketball at the Levelland middle school, says, “Our girls look like girls, and they act like girls.”

The fact that there are no female Charles Barkleys and Bill Laimbeers to serve as role models for athletic girls works in the coach’s favor too. “I don’t have to worry about girls getting influenced by seeing the hot dogs and prima donnas on TV,” Weese says. The fans reinforce Weese’s approach. They don’t care about dunks and wouldn’t approve of trash talk. “They like the way girls act over the way they see the boys act,” says Weese.

“Girls play a finesse game,” he adds. “Tech won last year with a finesse game—their kids weren’t the best athletes, but they knew how to play, they knew their strengths and weaknesses, and they had unselfishness—they knew Sheryl Swoopes had to score thirty points a game for them to win. ”

Marsha Sharp follows the script. “One of the most critical things about women’s basketball is chemistry,” she told me. “That chemistry makes things something that were nothing.” At 41, with her close-cropped hair and penchant for denim skirts and sweater vests, Sharp could be a suburban mom or a favorite aunt. She is unmarried, and basketball is her life. But for all her belief in chemistry, Sharp isn’t her own best example. She played high school ball at Tulia, south of Amarillo, but at Wayland Baptist she was too short and too slow to make the team and ended up first as team manager, then as a graduate assistant, which was a part-time coaching position.

Sharp attended Wayland Baptist from 1970 to 1975, when the Flying Queens enjoyed a national reputation and traveled great distances to compete against other formidable forces in women’s basketball—Mississippi’s Delta State, Virginia’s Old Dominion, and New Jersey’s Montclair State. At around the same time, the University of Texas women’s team was still wearing bows on their uniforms and meeting the opposing team for punch after the game. Wayland Baptist was crushing its opponents by as much as eighty points a game. The Queens flew to their games, thanks to the utter devotion of one fan, Claude Hutcherson, a rancher and owner of a flying service. In the fall of 1973 Weese became coach of the Flying Queens. His record with the team was 193–30, with four national championships in six years. Wayland Baptist was, like Tech is today, a team full of homebodies from high school squads like the Sundown Roughettes, the Winters Lady Blizzards, and the Munday Mogulettes. Weese never recruited from anywhere except West Texas and Oklahoma. Many former Flying Queens coach basketball today.

Everything changed for Wayland Baptist when the powerful National Collegiate Athletic Association, the governing body of men’s sports, executed what amounted to a hostile takeover of women’s sports in 1981. When the NCAA announced that it would hold championships for women, the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, which then oversaw women’s sports, was helpless to prevent its members from switching to the wealthier and more prestigious NCAA. The era when women could make their own rules, hold their own tournaments, run their own programs, and control their own destinies was over. At that time nearly every head of a women’s sports program was a woman. Weese was the rare exception, and he would leave Wayland Baptist in 1979. Today less than half of the coaches and athletic directors in women’s sports are women. When the big state universities got serious about women’s sports, the old powerhouses like Wayland Baptist were doomed. The big schools had better recruiting, better facilities, and more money to travel. Soon, thanks to a little-understood provision of federal law called Title IX, women’s sports would have even more money—so much more that in addition to fighting among themselves, women would soon be fighting men.

In the spring of 1975, University of Texas athletic director Darrell Royal went to the White House to talk to President Gerald Ford about a looming threat to big-time college athletics. His concern was that regulations were to go into effect to implement Title IX of the Education Amendments Act, passed by Congress in 1972. The law prohibited sex discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal funds, which means every school that plays major college sports, public or private. “Mr. President,” Royal recalls saying, “I’m not opposed to women’s athletics. It’s not a question of whether women’s sports are valuable. It’s a question of who is going to pay for them. ”

Title IX requires that three things be equitable for women: (1) Participation opportunities. This means that at each campus, the percentage of women playing sports must reflect the percentage of women who are enrolled. Nationwide, men constitute almost 70 percent of the varsity athletes but are just 50 percent of the undergraduate students. Under Title IX, either the number of male athletes must be reduced or the number of female athletes increased. (2) Scholarship money. (3) The athletic experience. This may include the number and quality of coaches, practice times and game times, travel arrangements, tutoring, publicity, anything you can think of. The problem here, as the men’s athletic departments see it, is that men’s sports bring in virtually all the money—from ticket sales, concessions, TV appearances, and donations. As the women’s athletic departments view the situation, however, whatever money comes in belongs to the university, not to men’s athletics, and should be spent on all sports, not just men’s sports.

Almost twenty years ago, Royal foresaw the infighting that would take place between men and women over money. Title IX has locked the destinies of thousands of young men and women in a struggle for entitlement. Sometimes civil rights goals can be in conflict. “If you are going to expect men’s programs to pay for the women’s programs,” Royal advised President Ford, “we are going to have to eliminate all non-revenue-producing men’s sports, like track, golf, swimming, and baseball, and give women money from football. You’ll be letting women play sports men are no longer allowed to play.”

If that sounds farfetched, consider the boycott threatened by black basketball coaches earlier this year. The threat followed a vote by representatives of NCAA schools not to raise the number of men’s basketball scholarships that a college may offer. The scholarship limit had been reduced to thirteen as a money-saving move, and the coaches protested that poor kids were being denied a chance to attend college. But the money saved helps fund women’s basketball, in which fifteen scholarships is the limit; the scholarships that aren’t going to poor young men are now going to poor young women.

“I don’t think politicians know what they just passed,” Royal had told Ford. But Royal knew. He loathed fundraising and alumni pressure and predicted that the enormous financial burden would fall upon the men’s program if it were responsible for women’s sports as well. He decided that women ought to have their own department and their own budget, to be funded by the university. He called in Donna Lopiano, who was the women’s athletic director at UT but was responsible to the same university committee that the men were, and said, “You ought to have your own athletic council. Otherwise we are constantly going to be arguing about money, and I don’t want to go through that.”

Being autonomous turned out to be a blessing. “That’s why UT became the premier program it did,” says Lopiano, who today is the director of the Women’s Sports Foundation in suburban New York. “We had an entire staff devoted to the development of this one product. You can’t do it any other way.” Under Lopiano, UT women’s athletic teams won eighteen national championships in swimming, track, and volleyball, in addition to basketball. After she left, Jody Conradt succeeded her as athletic director. But other schools have not followed UT’s lead in keeping the men’s and women’s programs separate. Today Texas is one of just four major schools—Tennessee, Iowa, and Minnesota are the others—that have an independent women’s program. Almost every other school in the country has one athletic department, and almost all of them are headed by males.

When Lopiano took charge of the new women’s department in 1976, she had instructions to hire the best coaches in the country and a budget of just $74,000 to do it with. Her first choice was Conradt, then the head coach at UT-Arlington, who came on board for $19,000. Within a year, Conradt made major changes in the basketball program. She installed a full-court press and fast-break attack that were unusual for women’s basketball at the time. Conradt added three assistant coaches, set a goal of winning a national championship, and upgraded the schedule. She took the team on an East Coast tour. Donna Lopiano’s parents put up the entire squad in their house, fed them meals in their kitchen, and lent them their station wagon, which Conradt drove around New England. The team whipped up on several ranked East Coast powers and came home with a national reputation.

In 1979 the Lady Longhorns were ranked fourth nationally, with a 37–4 record. The next season, Conradt won her first National Coach of the Year award. The team had stopped playing in antiquated Gregory Gym and moved into the Super Drum with the men. Attendance at games increased, UT cheerleaders and the Longhorn Band started appearing at games, and the Fast Break booster club was formed. The Lady Longhorns began to establish a following in the community. In 1983 the Lady Longhorns finished 30–3 and were ranked third. The next year, they defeated the University of Southern California and Cheryl Miller, who had been described by Sports Illustrated as the best player in the country. By February they were ranked number one and were outdrawing the UT men’s team. It was only a matter of time before Texas won a national championship, and the time came in 1986, with an undefeated season and another victory over USC. President Ronald Reagan invited Conradt to bring the Lady Longhorns to the White House. It seemed as if UT had established a dynasty that would last for years.

After winning the national championship, life was never the same for Jody Conradt. It was as if she had a legend to live up to and everything she did was somehow magnified. “Jody changed the year we won the national championship,” recalls a onetime staff member of the athletic department. “She put herself on a pedestal.” On the trip to the White House, Conradt and the team were photographed with the president, but as it happened, the assistant coaches were left out. They watched the picture-taking session with the tourists, standing behind ropes. In addition, says the onetime staffer, “She started behaving as if she were invisible.” In 1988 Conradt made a decision that has haunted her ever since. She hired as a graduate assistant a former Lady Longhorn player who was also a personal friend. Rumors that the two women were more than friends soon surfaced and spread throughout the team, the athletic department, and the Southwest Conference.

Colleagues and friends worried about the situation. Conradt had always preached over and over to her players to conduct themselves with propriety. “While you are a member of the Lady Longhorns, you are a student first, an athlete second, and a public figure third,” she would say. The woman who was such a stickler for appearances that she acquired the nickname the Plastic Lady seemed to have lost her sense of perspective. The two assistant coaches who remained from the championship season eventually left the team, though at different times. Conradt says that there was nothing more to her relationship with the graduate assistant than friendship, but what could she do? She had heard the rumors too and had been told of her colleagues’ concerns about them. She discussed the problem with the graduate assistant, and as a result, the assistant left the athletic department after only one year of what is normally a two-year tenure.

But that was not the end of it. Some players had been affected too. “At first we were so focused on winning that we overlooked everything else,” remembers one ex–Lady Longhorn who played in the late eighties. “But then we felt betrayed. You look up to a coach. She’s a role model or even a mother figure.”

In the years that followed, the Lady Longhorns never quite regained their former luster. They began to have some problems in recruiting. In 1990 they lost to Arkansas, ending their 183-game Southwest Conference winning streak. They lost the conference championship to Arkansas in 1991 and to Tech in 1992 before tying Tech in 1993. They haven’t won the post-season conference tournament since 1990. The same former player told me, “Jody had no control over our team because of what she had done, and the team knew that. I could see it on the court.” Standards seemed to be getting lower, she said: “Players would go out to gay bars at night. I told them, ‘You can’t do this—you are in the public eye, especially during the season,’ but they didn’t care. Things were stricter before. If we were caught going out at night, the coach would have had us up at six the next morning doing laps. Maybe she doesn’t have the same hold on the players because of what she did, or maybe the times are just different. ”

Conradt accepts the blame for the Lady Longhorns’ perceived decline—but for different reasons. “I failed miserably as a coach,” she says. “I could not get the group of players who just graduated to develop any chemistry or idea of ‘team.’ It made me wonder whether I’d lost it.” Conradt had an opportunity to slip quietly out of the spotlight when Donna Lopiano left her job as women’s athletic director. Then-president William Cunningham offered to promote Conradt, but she didn’t want to quit coaching. Negotiations dragged on for months. Conradt was named interim director while a year-long search for Lopiano’s replacement commenced. Five candidates—none with impressive college experience—were perfunctorily considered. After a year, Conradt got the athletic director’s job and UT’s blessing to remain as basketball coach.

Although the American-Statesman articles dealt only with lesbianism among players, Conradt told me that the publicity hurt her personally. She calls last August, when the articles appeared, “the most difficult time for me professionally, ever.” She chose to publicly ignore what had been written, and the UT administration did not comment. But Conradt wondered privately why none of her fellow coaches stood up for her. The silence of nonsupport was deafening. Conradt learned that every player she had recruited that season had received, anonymously, copies of the article through the mail. “It hurts every time I have to relive those articles,” she told me, “but the competitive side in me wouldn’t let innuendo force me to do something I didn’t want to do—quit.”

The articles have had an effect on UT’s ability to attract players. One recruit Conradt had counted on was Katrina Price, a powerful forward from Waco’s La Vega High School. Last year Price averaged 25 points a game and led the Lady Pirates to a 26–3 record. She was recruited by more than fifty colleges but had always expected to go to UT, which had been pursuing her since her freshman year in high school. Lady Longhorn assistant coach Annette Smith had expected the same thing, so when Price informed Smith in October that UT was out of the running, Smith was surprised—and even more surprised when Price chose Stephen F. Austin University, in Nacogdoches. The Ladyjacks have always been a reputable team but lack the budget and the mystique of the Lady Longhorns. Their media guide displays the coach and two players—both decked out in evening dresses—on the cover. The brightly heterosexual message can’t be missed, and Katrina Price admits the contrast to UT made a difference. About the series in the Austin paper, she says, “That’s sort of what really changed my mind. It scared me.”

The articles changed fans’ minds too. Conradt’s home answering machine crackled with belligerent anonymous messages. She began receiving letters, many of them angrily scrawled, that said things like “I will never give you any more money as long as there are lesbians on your team. Cancel my season tickets.” Her successes were forgotten: her average of more than thirty victories a season, her winning percentage of .803, her three awards as National Coach of the Year, her 620 victories (as of the 1992-1993 season) —more than any other active female coach in America.

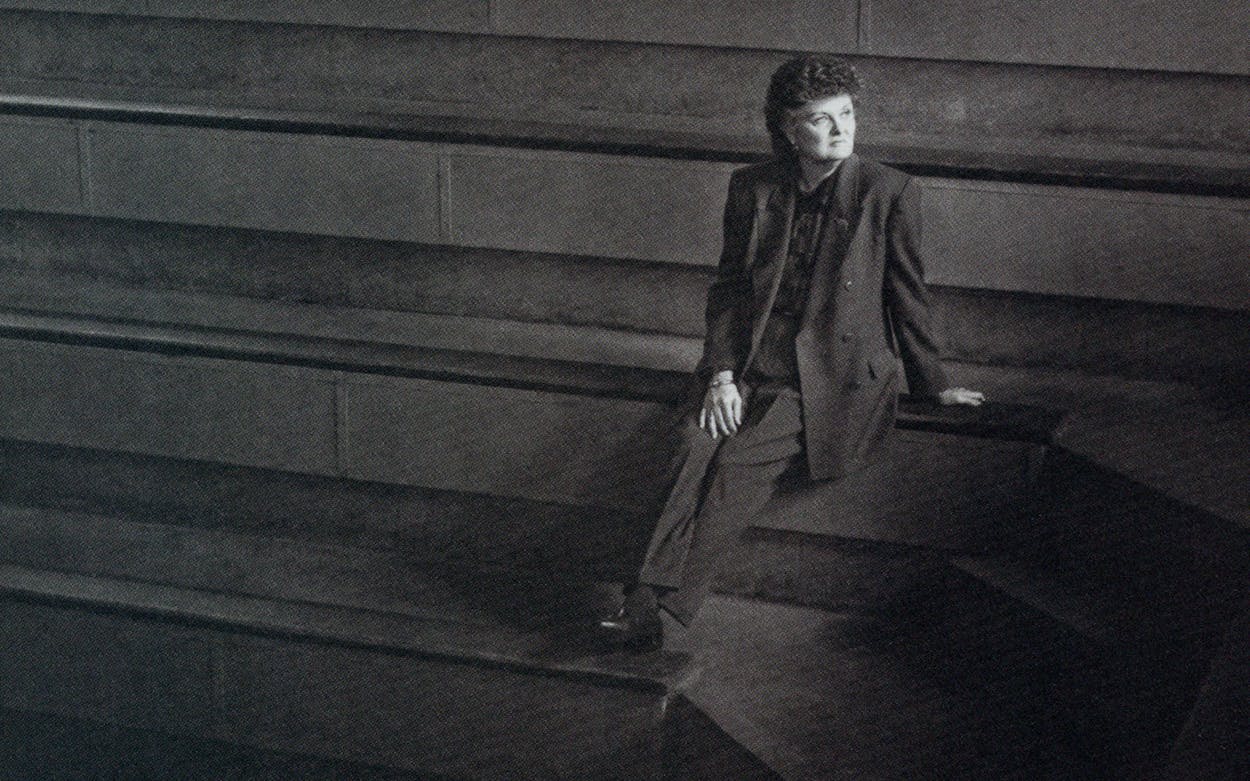

In person, Conradt radiates warmth and power. She wears a perpetual smile, but above it she looks out at the world with intense blue eyes. In the on-the-record portion of our conversation, she revealed little about herself except to talk about growing up in Goldthwaite, a hundred miles northwest of Austin, and about the influence of her mother. In an article in the American-Statesman that appeared on Mother’s Day 1993, Conradt reminisced about watching her mother play softball and how beautiful she was. “I was determined to have them talk about me the way they had talked about my mom,” she said. But the smile fades when we talk about the difficulties athletic women have encountered. “Being an athlete is different for a woman than for a man. You have to be willing to step out of the traditional role, to face some barriers, to face critics who say it is unfeminine,” she said. Now the blue eyes are pensive. “Every woman who participates in sports has had to turn to herself and face her inner strength. The sexual orientation issue is not new, but it is being used in ways that are intended to damage women’s athletics. I am totally dismayed and cannot believe the direction we are now heading. ”

If UT was getting battered on the public relations front because of the lesbian issue in women’s athletics, it was also getting battered in the courtroom. In July 1992 four female students sued the university—the school with the best women’s athletic program in the country—for noncompliance with Title IX. UT’s enrollment was 53 percent male and 47 percent female, but the ratio of participation in varsity sports was nowhere near equal: 77 percent male, 23 percent female. The figures were heavily skewed by football, which requires a large number of male participants, but that was not a defense that would stand up in court. The plaintiffs wanted to add four varsity sports for women: soccer, softball, crew, and gymnastics.

No Title IX lawsuit had ever been so sweeping. In fact, implementation of Title IX had been sluggish for the two decades since its inception. The seventies passed without much enforcement, while the government labored over details of how universities should comply with the new law. In 1984 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Title IX’s penalty of withholding federal funds applied only to specific departments rather than to the entire school. If, for example, the math department was discriminating against women, then it could lose federal aid, but the history department would not be affected. This ruling was a victory for men’s athletics, because they received almost no federal funds and thus were immune to federal attack. But in 1987, Congress passed (over President Reagan’s veto) the Civil Rights Restoration Act, which held universities responsible for Title IX violations, regardless of whether the department being challenged received federal funding.

Before the UT case, most Title IX lawsuits were defensive in nature—cases in which female students sued to bring back women’s sports that had been eliminated. The UT case was the first case in which women were on the offensive, seeking new sports and new handing, and the first case against a major football university. UT agreed to a settlement. It will add the two sports that are widely played in Texas high schools—soccer and softball—and provide facilities for them. In addition, the university will increase the number of female walk-ons (nonscholarship players) and reduce the number of male walk-ons in football. The university also must work toward a goal of having 44 percent of its athletes and 42 percent of its scholarship athletes be women.

Every university in America that participates in big-time athletics and receives federal funds is vulnerable to a Title IX lawsuit. “The impact of the settlement is just setting in,” says Diane Henson of Austin, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs in the UT case. “UT was in better shape than anybody. Other schools will fare much worse.”

Texas Tech, SMU, and Baylor are also involved in Title IX disputes, as well as many schools outside of Texas, including the entire University of California system. The impact these lawsuits are going to have is staggering. Universities do not have money lying around with which to fund women’s athletics. The funds can come only from men’s athletics. At UT, contributions from the men’s department to the women’s have climbed from $200,000 in 1985 to almost $ 1 million this year.

To get an idea of how other schools may be affected, consider the situation at Baylor, where women’s basketball coach Pam Bowers was fired and then rehired after she threatened to file a Title IX lawsuit. The men’s basketball program has three assistant coaches. Bowers, the women’s coach at Baylor since 1979, had no assistant until last year. The men ride to games in chartered buses. The women ride in vans—and Bowers drives. In past years, she has even had to sweep the gym floor and do the team’s laundry. The men’s budget is $672,828. The women’s is $314,464. The men spend $68,000 on recruiting. Bowers spends $13,500. In addition, the women’s games are scheduled at five-thirty, two hours ahead of the men’s games. But don’t plan to park anywhere near Ferrell Center, where the games are played; the parking lots are reserved for patrons of the men’s games. Women’s fans must park in the remote parking area, which is actually a field.

The fugue of fear and anger that resulted from the American-Statesman’s articles proved that in at least one sense, women’s athletics was equal to men’s: It’s just as dirty. Title IX and lesbianism might seem like separate issues, but they are linked, because Title IX poses a threat to men’s sports and women believe that revelations of lesbianism are the men’s secret weapon. In a response to the series on homosexuality in the American-Statesman, Jan Lahodny, a girls’ basketball coach in Victoria, wrote, “Homosexual labeling raises its ugly head every time there is a Title IX sports equity victory in favor of women’s athletics.” She continued, “There is virtually no avenue for women’s coaches with families to enter the college coaching ranks. The primary reason is the travel required to recruit successfully. Most mothers, as myself, are not willing to be away from their children for days at a time.” The result, Lahodny said, was that single women were competing with men for women’s coaching positions. “The easiest way to shoot down the single women is to label them lesbians.”

Title IX has forced the assimilation of two ideas of sports that are basically incompatible. The men’s model is based on the dream of a professional career in sports. The single-minded pursuit of sports is the best way to achieve that dream. Being in the public eye is essential to the package of success. The women’s model has none of this. Its roots are in physical education departments. The goal of women’s sports never was professionalism; it was recreation. But Title IX has changed all that. Women’s athletics is well on the road to being professionalized. Women athletes will have to be prepared, whether they like it or not, for the scrutiny that goes along with being in the limelight, and lesbianism, at least for now, is a PR nightmare.

You would be hard-pressed to find a prominent woman in athletics who didn’t believe that the American-Statesman articles weren’t planted to discredit Conradt, her athletic program, and especially, all of women’s sports—perhaps by a UT men’s booster or administrator who was annoyed that the football and basketball teams were being forced to give up a few players. “Nobody thinks those articles were an accident,” fumed Nancy Lieberman-Cline, a former guard at Old Dominion in the early eighties and now a sportscaster for Home Sports Entertainment and NBC. “Jody is the most powerful woman in sports today. Sometimes when people get too good, we get jealous.” Donna Lopiano agreed: “I’m really, really upset about the articles. In my seventeen years at UT, I was more aware of problems with men’s sports than with women’s. Did that ever get to the press? With Title IX, we have to expect hardball now.” (According to Statesman sports editor Tracy Dodds: “There was no need to plant this story, because it is an issue that comes up on every beat we cover. There were numerous attempts to stop this story when it was in the planning stages.”)

But finding a man willing to talk on the record about the tensions between men’s and women’s sports is as hard as finding someone to talk for the record about lesbianism. UT’s men’s athletic director DeLoss Dodds (no relation to Statesman editor Tracy Dodds) is the model of discretion. His remarks are so general and all-encompassing that they hang in the air with platitudinous significance. “Everything will work out,” he intones from his plump leather chair.

Not for attribution, here is what some present and former men’s administrators told me: Men’s sports bring in revenue, and women’s sports don’t. Yet men are being forced to support the women. Student athletic fees have to be split with women, but if men’s football and basketball weren’t part of the package, no one would buy it. If women attracted fans, they could pay their bills and Title IX wouldn’t be necessary. They aren’t even appreciative of the men’s largesse. Women are trying to take more than their own share, and they’ll never be satisfied until they’ve emasculated—the characterization is a Southwest Conference official’s, not mine—football.

But the real issue, said Jody Conradt, is, Whose money is it? “It’s an emotional issue who that money belongs to,” she said. She was sitting in her institutional-type office, not nearly as large or as plush as DeLoss Dodds’s, on her institutional-type couch. At 53, she looked luminous in a brand-new white UT jogging suit and gleaming sneakers. “That’s basically the whole argument. Who does that money belong to? For instance, does the men’s tennis team deserve it any more than the women’s tennis team? If a male professor in the chemistry department does research that wins prize money, would all the money go to the entire department or would it go to just the men in the department?” Of course, as Conradt knows all too well, the athletic department isn’t the same as the chemistry department. Chemistry is important, but it isn’t emotional.

It is the opening night of basketball season at a small-town high school, and students and their families have turned out for an event called Family Fun Fest. The pre-season games will be starting in a couple of hours, but first one of the coaches has gathered her girls together for a talk during a dinner of pizza. The subject is homosexuality. They are assembled in the home economics room at tables flanked on both sides by stoves, refrigerators, and other accoutrements of traditional family life. She begins the discussion with a prayer. The girls range in age from thirteen to seventeen; two of them already have children. Then the coach gives the girls a test, Index of Attitudes Toward Homosexuals, with such statements as “It would disturb me to find out that my doctor was homosexual.” The scores, graded on a “homophobic scale,” average in the low seventies, indicating that the team is “moderately homophobic.” Then the coach moves into a frank chat, mentioning words like “sodomy” that she knows the girls’ parents have never uttered around their children. She is frequently interrupted by nervous shrieks and giggles from the girls, but presses on, explaining what homosexuality is and that it exists everywhere. Finally she gets to her main point. “There isn’t a college sports team in the country that doesn’t have lesbians,” she says. “The reason you are hearing so much about it now is because college recruiters use this as a negative recruiting tool. They use it against the University of Texas because its program and its coach are so powerful.” After the session is over and the girls leave the room, the coach buries her head in her hands. “This is killing me,” she says despairingly. “I’m encouraging these kids to go to UT because the program is so good. But I wish that high school coaches would prepare their athletes for possible seduction by other women. We would all be happy if we knew that UT and other colleges were dealing with the lesbian issues up front.”

Maybe things will be different for the 1994 Lady Longhorns. Most of last year’s talented but underachieving team has graduated. A controversial assistant coach has also left UT. Conradt seems relieved that the veteran players with long memories are gone. “There was no way I could make that team come up to my standards of discipline,” she said. Now she has the opportunity for a fresh start with five freshmen—three of them starters. It’s a smaller, faster team, and a subtler change is that the newcomers are almost adorably cocky, pert, and wholesome. These young women look very different from the broad-shouldered bruisers of years past. They don’t feel the burden of being Lady Longhorns. “Because it’s UT, I think we’ll all step up and play better than we ever have,” freshman point guard Angie Jo Ogletree told me with a toss of blond curls.

With two minutes and fifteen seconds to go in the game against Texas Tech, Ogletree drives in for an easy jump shot. The ball swishes in, and Texas, which had trailed 13–0 and had gone scoreless for more than seven minutes early in the game, is behind by just one point, 63–62. The lead seesaws: 64–63 Texas, 65–64 Tech, 66–65 Texas. Twenty-five seconds to go. Ogletree commits a foul, but Tech misses a free throw and loses a chance to go ahead. Fourteen seconds to go. Now Texas misses a free throw. Tech has the ball. Time out! Three seconds to go. Connie Robinson has the ball for Tech twelve feet from the basket. UT center Benita Pollard is in her face. The shot is away and the ball wobbles on the rim. It falls off. The buzzer sounds. Texas wins.

The delirious Lady Longhorns crowd around their coach in a jubilant mass hug; then a beaming Jody Conradt extricates herself from the crush. With the confident stride that comes from experience, Conradt walks toward the glaring lights and expectant faces of a television crew and effortlessly slips into a role she has played so many times before, turning on a brilliant smile and giving the hook ’em sign. “This was,” she says, “probably the most satisfying game I’ve coached in my twenty-five-year career.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin