This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“I was raped. I guess it was my own fault in a way, but I was passed out when it happened. It was my first time and I didn’t even know what was happening. I still feel bad about that.

“I knew I was pregnant and I just couldn’t tell my parents. I sneaked a urine sample out the window to a friend who worked in a lab. It came out positive. I was just desperate and I had to have an abortion, but it wasn’t legal then. I got my parents to let me visit a friend in St. Louis. She found this place in the slum section and I went down there—it was the whole back room thing. This guy inserted a catheter. When I went back to my friend’s house, the catheter fell out and I was bleeding, but I couldn’t say anything. I flew back home, still bleeding. The abortion hadn’t worked.

“My brother told my parents and they took me to a doctor who said the baby would be deformed. My father took me to a place in Mexico City. It was really insane. We had to go from one hotel to another and they picked us up on a street corner in this big car. They tried to induce a miscarriage but it still wouldn’t work.

“What was supposed to be a two-day stay ended up being two weeks. I finally miscarried naturally.

“I was screwed up for two years after that. I had a nervous breakdown. I was taking drugs—speed and the whole bit. I’m all right now, but it’s taken a long time.

“I don’t like to hear jokes about abortion—you know coat hangers and stuff. Maybe no one who hasn’t been through it will ever really understand.”

Jan is 22 now, and earning a degree in social work. Between school activities, she works with women who have problem pregnancies. She knows their fears and problems because she’s been through it—the hard way.

Jan’s story is not an unusual one. Before abortion became a legal alternative for a problem pregnancy, these experiences were a dime a dozen—women who were desperate enough and who wanted abortions got them, and in the process, some, like Jan, paid the price of mental and physical suffering. Then in 1973, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling which removed criminal sanctions against the performance of the procedure. This cleared the way for physicians to perform abortions for private patients and for agencies in many states to set up abortion clinics. In an effort to see what effect that decision has had in this state, Texas Monthly decided to look at the abortion situation in Texas. Is abortion a safe, legal, available alternative for Texas women with problem pregnancies? The answer is a highly qualified “yes.”

A middle-class white female Texas citizen living in Dallas, Houston, or San Antonio can now obtain a safe legal abortion without much trouble. Women who are young, black, or chicana, who are financially pinched, who do not have a private physician, and who live anywhere else in the state have a very good chance of having an experience like Jan’s.

Some women, out of desperation or ignorance, are going to the illegal abortionist. Some who would have chosen abortion are carrying unwanted children to term because they could not get to a doctor or an abortion clinic in time. Many don’t have the money. And many just can’t get access to the facts.

On January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Roe v. Wade—a case which came from Texas and was handled by State Representative Sarah Weddington of Austin. The seven to two ruling, written by justice Harry A. Blackmun, states that allowing abortion only as a life-saving procedure, without regard for the stage of the mother’s pregnancy and other interests involved, violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court stated that a woman has a qualified constitutional right to terminate her pregnancy. The ruling overturned the Texas criminal abortion statute and left the state with no laws regarding abortion. The only rules now in effect are those set down by the court.

The court delineated three stages of pregnancy, allowing more state authority over the procedure as the pregnancy progresses. In the first trimester (12 weeks) of pregnancy, the decision to have an abortion lies with the woman and her physician. In this stage, the right is in full force and the state can make no laws abridging it. During the next six months of pregnancy, the court said that states may “regulate the abortion procedure in ways related to maternal health.” This means, for example, that the state can license and regulate the persons and facilities involved in doing the procedure. During the last ten weeks of that six-month period, the state can regulate or forbid abortions except when they are deemed necessary to preserve the physical life and health of the mother.

The court ruling did not give women the right to “abortion on demand.” Instead, it said that the decision “vindicates the right of the physician to administer medical treatment according to his judgment up to the points where important State interests provide compelling justification for intervention. Up to these points, the abortion decision in all its aspects is inherently, and primarily, a medical decision, and basic responsibility for it must rest with the physician.” In essence, the Supreme Court decision allows physicians to perform abortions without fear of criminal legal reprisals. It allows a woman to have an abortion up to a certain stage of pregnancy (in effect up to about 24 weeks), if she can find a physician who will do it.

Availability of a physician is not assured. Texas ranks last among the ten largest states in ratio of physicians to population. There are about 13,000 non-federal physicians in Texas serving 11,200,000 people, for a ratio of one MD to every 861 patients. The national ratio is one to 674. Obstetrics-gynecology is the specialty area which includes abortion, and the Texas Medical Association (TMA) says the state needs 400 more obstetrician-gynecologists to meet population needs. In addition to a doctor shortage, there is a distribution problem. Physicians are locating in the more populous counties of the state at a higher rate than the actual migration of the population, leaving a medical care gap in rural areas. There are 23 Texas counties with no MD. And the field is further narrowed by two other factors: Many physicians are opposed to performing abortions for any reason. Many hospitals do not allow abortions, or make it too difficult financially and bureaucratically to obtain one. Here, social, sexual, and religious attitudes are having an effect.

The Doctors

In the March 1973 issue of Texas Medicine, Dr. Braswell Locker, former president of the 11,500-member Texas Medical Association, had an article about abortion. Titled “Ethics,” it said, in part:

There are many things that are legal that may not be right in the eyes of God. Let’s weigh our decisions very carefully, be sure we are right, and then go ahead and do every job as though it were for the Lord. . . .

Medicine without an ethic; the law without a norm; and the religious community without a theology of life and death, man and nature; will leave people without a defense. This is particularly true in a world where so many are willing to sacrifice the other rather than sacrifice for the other.

Doctors may be reluctant to perform an abortion for many reasons. Some are Roman Catholic and thus forbidden by religion from terminating a pregnancy. Some fear that patients who want an abortion today will regret it tomorrow and blame the physician. Some still are not clear about the law; others fear extra-legal reprisals from peers who oppose abortion. And some physicians, because of their upbringing or their personal sexual attitudes, either refuse to think about the subject or have strong moral objections to it.

Private physicians who do perform abortions in Texas are often reluctant to admit the fact publicly.

The practice of medicine is a closed society. Physicians are under increasing pressure from outside the profession to provide better, cheaper, more accessible medical care; their only defense to what many doctors consider attacks on the profession is to band together into associations to protect their interests and uphold good standards of practice. These associations cannot make laws; they do, however, make policies to which most doctors are careful to adhere. For medical doctors (MDs), this association is the TMA. For osteopathic physicians (DOs), in addition to the TMA, there is the Texas Osteopathic Medical Association (TOMA).

TMA policy on abortion states that medical staffs should formulate local policies covering abortions designed to safeguard the patient’s health or to improve her family life. The TMA accepts that abortion may be performed at a patient’s request or upon a physician’s recommendation, but is careful to state that no doctor or other health care personnel may be required to participate in performing an abortion. The policy also states that the doctor must obtain the informed consent of the patient (in the case of a minor from her parent or guardian). TMA policy does not specifically prohibit doctors from performing abortions in their offices if emergency facilities are available.

TOMA policy, which governs DOs, is not as specific as that of the TMA. It says only that the bylaws of TOMA “do not prohibit a physician from performing an abortion that is performed in accordance with good medical practice and under circumstances that do not violate the laws of the community in which he practices with the understanding that no physician shall be obligated to render such treatment against his will or in violation of his good conscience.”

Officially, physicians who perform abortions have nothing to fear from their medical societies. Practically, the situation is different. A physician who flouts local convention by openly doing abortions can suddenly find that patients are no longer referred to him by other physicians; he may find that his privilege to practice in a hospital is endangered; one Dallas physician stopped working at a private abortion clinic for this reason. Doctors in San Antonio and Austin have been talked back into line by colleagues who do not approve of the way they conduct their practices.

Texas doctors who choose to do abortions must have more than a little courage. The situation is gradually changing, but there is an obvious philosophical gap between doctors who do large numbers of abortions and those who do them only for their own patients and then only rarely.

In Austin, for example, at the time of this writing, no more than three or four private doctors are routinely doing abortions; in El Paso, a social worker reports that only two physicians will perform abortions on any regular basis.

One Austin physician went, when the Texas case was on appeal, to New Mexico to learn the technique for vacuum aspiration, then a new procedure. (Other Austin physicians have gone to New York, California, and North Carolina for similar training.) After the decision, he found there was no vacuum suction equipment in town. Moreover, Brackenridge, the city general hospital, did not have money budgeted to buy the equipment. Finally a private donor—not the doctor himself—loaned the equipment to Brackenridge.

The Austin situation began to change—some private patients were able to obtain abortions from their doctors. But women with no private physician and women who were charity patients still could not get abortions in Austin. Doctors were afraid to do them or just didn’t want to. In a few cases, the doctor was willing but auxiliary personnel like anesthesiologists were unwilling to cooperate.

With the donated equipment, the private physician now does abortions without pay for charity patients at Brackenridge Hospital, using his own money to buy supplies. Other local physicians are learning the procedure. Eventually, this doctor hopes, enough trained physicians will be available in Austin to ensure that the women of the city can have safe, easily accessible abortions if they choose to do so.

He has met with some criticism from his peers. He feels that there may be a stigma attached to being thought of as an “abortionist”: “I haven’t had any direct pressure,” he says, “but I have felt the stigma at times. There are some doctors who will never accept abortion. But as more physicians begin doing them, the anger will diffuse.”

What makes a person give of his time, his income, and his knowledge for a cause which may make him unpopular among some of his peers? “I believe that there is an inevitability about abortion. If it is not done legally, it will be done illegally. If a patient is determined to have an abortion, I believe it behooves me to see that she gets quality medical care.” Slowly, very slowly, the situation seems to be changing.

Meanwhile, Austin doctors tell of seeing the results of illegal abortions which still are being done (by “the woman,” or “the nurse” in San Antonio or wherever), and of complications of abortions done in private clinics out of town which provide no follow-up or emergency care for the patient.

Dr. William McLean of Austin is president of the Texas Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (TAOG) , which is one of the specialty associations which sets standards for physicians who do abortions. The TAOG position is substantially similar to that of the TMA and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG). Dr. McLean doesn’t feel that it is difficult for women who want an abortion to get one. He feels that abortion is accessible even for charity patients: “Sometimes charity patients get taken care of faster than private patients,” he says.

While many physicians see definite disadvantages to abortion clinics—the principal one being lack of emergency and follow-up care—Dr. McLean says that a well-run clinic can be quite satisfactory. He does see an occasional botched job from an illegal abortion, but he feels that women who seek illegal abortions do so because it is less expensive rather than because they cannot obtain a legal abortion. (Physicians experienced in abortion work say this is not necessarily true.)

Dr. McLean says that the technique of performing an abortion is not that hard to learn and that medical schools, while they haven’t specifically taught abortion techniques in the past, have taught procedures which are similar enough to those used in doing an abortion that they would enable the trained ob-gyn to do abortions without substantial additional training. In addition, since abortions have become legal, equipment which facilitates the procedure has been perfected. If abortions are ever declared illegal again, the process, even though it may not be done by a physician, may be safer because of the invention of new equipment.

Apparently, however, lay people who do illegal abortions in Texas haven’t kept up with the technological advances. One doctor reports seeing a patient whose uterus had been packed with gauze by a lay abortionist. The use of gauze packing can cause perforation of the uterus and bladder, and even death from infection or hemorrhage. Bits of gauze were found clinging to the patient’s uterine wall six weeks later. The woman was severely ill. She told her physician that she sought the illegal abortion out of desperation. The only physician she knew did abortions only on Tuesdays and Thursdays. The only days she could get off from work were Mondays and Wednesdays. The illegal abortionist was able to accommodate herself to the woman’s schedule.

The Hospitals

Any abortion done after the 11th or 12th week of pregnancy must be done in a hospital, because procedures done after this time involve inducing labor and subsequent miscarriage of the fetus. Abortions done prior to the 12th week can be done in physicians’ offices or in hospitals on an outpatient basis, but few Texas hospitals we surveyed allow this sort of outpatient surgery.

All hospitals are governed by a board of trustees or directors in conjunction with a medical staff. The medical staff of a hospital consists of private physicians who have “privileges” (meaning that they can admit and treat their patients at that hospital). Most Texas hospitals belong to the Texas Hospital Association (THA), but their internal policies are a matter of individual choice. No private hospital is required to allow abortions to be performed within its walls.

If the governing board of a hospital decides to allow abortions in its institution, guidelines are set up which dictate what kinds of procedures will be allowed, what kinds of consent and consultation are needed, and who will perform the procedure and when. If the hospital governing board and medical staff are opposed to abortion, they will either forbid its being done in that institution or make it difficult enough that patients will probably go elsewhere.

Hospitals can discourage abortions by requiring patients to stay overnight for what can be an outpatient procedure, thus making it more inconvenient and more expensive; by requiring consultation with several other physicians or social workers; by allowing only “therapeutic abortions”; by requiring consent forms from several persons other than the woman herself. It is impossible to determine how many Texas hospitals use these kinds of tactics and whether or not they are used specifically to make it difficult for the procedure to be performed in that institution.

Public hospitals are one example. There is or has been controversy in every Texas city over abortion policies of publicly supported hospitals. These hospitals are financed by tax money for the health care of all the people of the area, especially the indigent. Many who are on Medicaid or who are just above the poverty line use the public hospital as their sole source of health care. Public hospitals generally have outpatient clinics where patients can receive treatment for ailments which do not require hospitalization. Public outpatient facilities for abortion, however, are rare, if not non-existent.

The Austin city manager has refused to allocate money for abortion equipment despite endorsement of the request by the Brackenridge ob-gyn staff. In Houston, Jefferson Davis Hospital began providing abortion facilities for Medicaid patients in September 1973. At Dallas’ Parkland, one source says that fewer abortions are being performed now than were done before the Supreme Court decision. Fort Worth’s John Peter Smith Hospital allows abortions under certain conditions. Some groups are considering lawsuits against Texas public hospitals in an attempt to force them to provide abortions. State Representative Sarah Weddington says that several national suits are pending which may give courts precedent from which to work.

Meanwhile, hospitals across the state have policies which range from comparative permissiveness to complete prohibition. In general Texas hospitals which allow abortions at all require that it be done on an inpatient basis. Most ask for at least one consultation, and one prefers as many as four. All hospitals require the consent of the woman and of her husband (including common-law), or of her parent or guardian if she is under 18. On the other hand, only two responding hospitals stated that they require counseling.

The Clinics

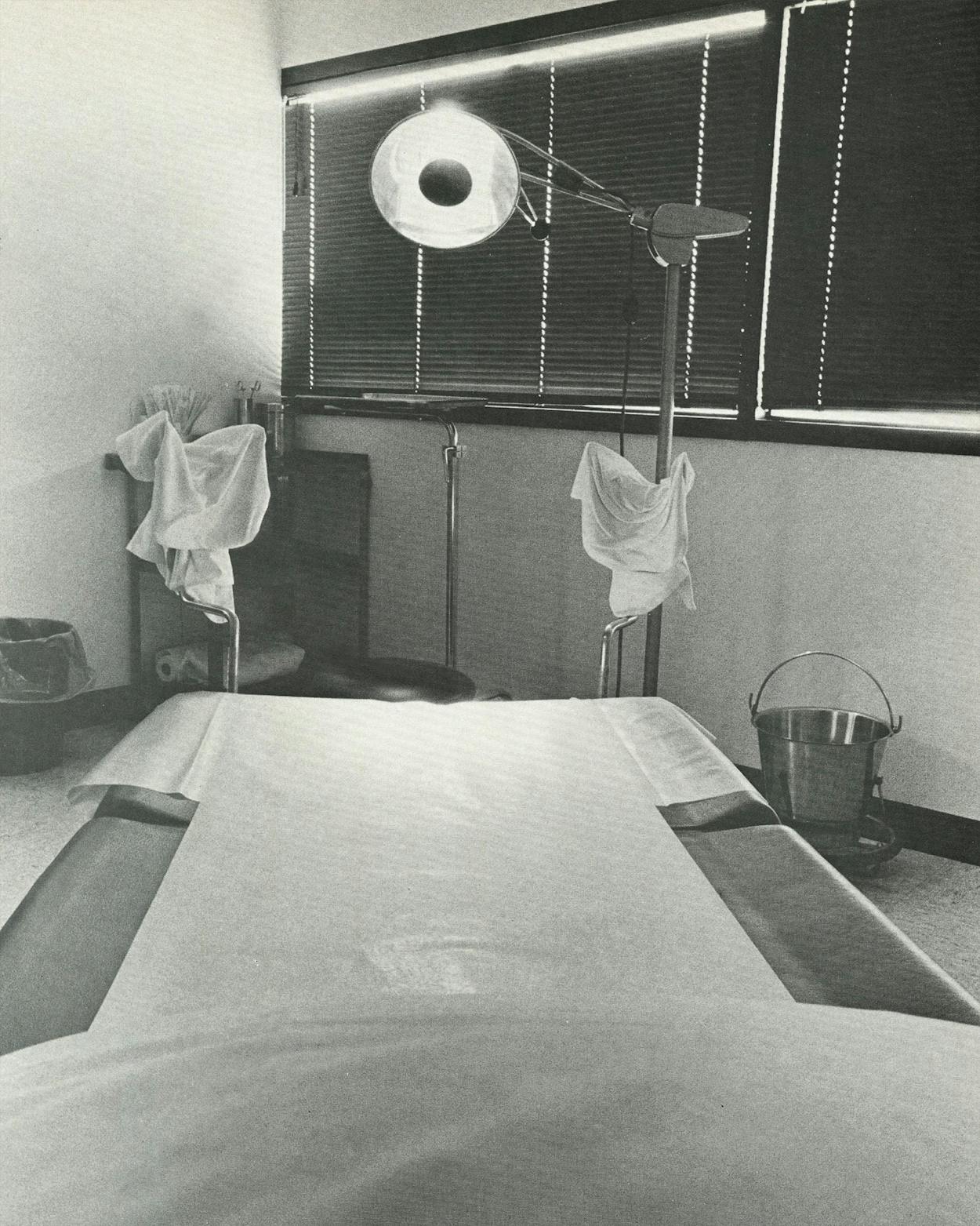

The emergence of free-standing (not connected with a hospital) abortion clinics in Texas is a response to the fact that private doctors do not perform and hospitals do not accommodate significant numbers of abortion patients. In order to fill the need, clinics, which provide legal, reasonably safe abortions for large numbers of women, have begun to take hold in Texas.

There are eight abortion clinics in the state—three in Dallas, four in Houston, and one in San Antonio. More may be opening soon in Dallas and Houston, but no reports of new facilities in other towns have been received. Free-standing abortion clinics are operated either because people who believe in abortion start them for humanitarian or philosophical reasons or because the people who run them want to make money. Prices for abortions done in clinics range from an average of $150 for vacuum aspiration up to about $500 for a saline or a uterine induction. The lowest price is around $50 for an endometrial aspiration. Hysterotomy must be done in a hospital and is not offered by any clinics which are presently operating. For these prices, the abortion patient usually receives all lab tests, varying amounts of counseling, the procedure itself, and a supervised recovery period. A few clinics dispense birth control medication and prophylactic antibiotics. Still fewer provide for a follow-up visit to a physician two weeks after the procedure. Most clinics do abortions only until the 12th week of pregnancy. Three—one each in Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio—take patients up to the 20th week of pregnancy.

A free-standing abortion clinic, if operated safely and efficiently, can be the answer for the woman who chooses to have an abortion. Nonetheless, there are disadvantages inherent in the operation of a clinic which does not have access to hospital facilities.

“The problem with commercial clinics is who is in charge,” says an Austin gynecologist who performs abortions for his private patients. “The medical profession is slow to agree, and with justification, to put medical care into the hands of laypersons because the board of a commercial clinic can only be oriented in two directions: profit, or a philosophical position so strong that they forget the nuts and bolts of the operation.”

“Free-standing clinics are not the answer,” he said. “The private physician who does an abortion is always available for consultation. Where is the doctor from a free-standing clinic at night? Where does the woman turn if she needs help? Does she even know the doctor who did the procedure? Clinics now are performing vital functions but they can be faulted on two points: the availability of a doctor at all times and one other which concerns procedure.”

The doctor explained that, in a free-standing clinic where the abortion procedure takes about three or four hours, the cervix is dilated with metal instruments which may at times damage cervical fibers and cause problems with later pregnancies. A private physician with more time, using a sterile seaweed insert, can dilate the cervix gradually, over a period of about six hours, lessening the chance of cervical damage.

A defender of the free-standing clinic is Len Sands, director of Planned Family, Clinic, Inc., in Dallas. Planned Family is a commercial operation, part of a national organization called Planned Family Center. Other clinics are operated in Detroit and New York. Most of the staff physicians at Dallas Planned Family are flown in from Detroit each week.

While Sands says his operation has been received warmly in Dallas, there are signs that the reception will soon change from warm to hot. Planned Parenthood of Dallas does not recommend the clinic. The Texas State Board of Medical Examiners has the clinic under investigation for not having a pharmacy license, and for employing physicians who are not specifically licensed to practice medicine in Texas. In addition, it is against Texas law for a corporation to employ physicians unless the board of directors is composed of physicians. Only one complaint from a Planned Family patient has been reported to Texas Monthly, however.

Sands is not afraid of a fight. He considers himself a pioneer in the abortion business. “I’ve been campaigning and fighting for abortion since 1965,” he says. “It was my attorney who brought the class action suit in Michigan that legalized abortion in the state.” He says physicians who work at the Planned Family Clinic are all reciprocally licensed to practice medicine in Texas and that his clinic maintains the highest standards of care.

Sands says that Michigan physicians are used to staff the clinic because they have had more experience in doing abortions than Texas physicians. Some Dallas-area doctors do work at Planned Family, but only after they have been trained by the Michigan physicians. The pattern of physicians training other doctors to do abortions is a common one, says Sands.

“New York was the only state where abortion was available by consent of the patient and the physician. Reciprocally licensed Michigan physicians went to New York to help New York doctors cope. Michigan physicians opened a clinic in New York. I’m not going to put a patient under a physician who’s unskilled. We get patients in here who’ve been examined by doctors who’ve told them that they’re nine weeks and they’re 17 weeks. Physicians have not had to be that skillful in determining the exact stage of pregnancy until now. Up until this time, they haven’t cared. It’s very disheartening to the patient.”

Not only is it disheartening for a woman to be told she’s further along in her pregnancy than she thinks—it’s expensive as well. A woman who went to Planned Family reports being told when she was on the table ready for the physician to do the abortion that a higher fee would be necessary because she was further along than had been supposed. She had to pay the money immediately, in cash.

“We have 24 rooms here,” explains Sands. “We have our own lab. There are four full-time counselors who are graduate psychologists. There’s a great deal of apprehension about a procedure that is simpler and safer than a tonsillectomy. We do everything possible to lessen the anxiety. I feel it’s vital, for example, to have a well-decorated facility.” Sands spent from March until August, 1973, looking for an office he felt was presentable for the clinic. When he told landlords what he wanted to use the building for, they lost interest in leasing.

Doctors, too, must meet standards. “I have a trick question I ask before I hire anybody,” says Sands. “I ask, ‘What are the conditions under which abortion is justified?’ If they have any, I don’t hire them. They must believe abortion is a woman’s right.” They also must believe in clinics. “An office is no place to do abortions,” Sands says. “We’re not trying to do anything here but abortions. We’re specialized. We’re not doing anything that a doctor wouldn’t do in his office. We’re not trying to disrupt the medical community; we’re trying to fill the void in it.”

The clinic also has been criticized by people who think Planned Family is responsible for billboards in Dallas which proclaim, “Need an abortion? Call . . .” Sands says these billboards belong to a service called Abortion Centers of America, which refers women to other agencies besides Planned Family and also does family planning counseling.

Most referral services which advertise on billboards are not free—some charge as much as $50 for referring a pregnant woman to a clinic or counseling service she could find in the phone book.

Whatever the quality of care may be, Planned Family gets patients from all over Texas and adjoining states. Sands says that the clinic is now doing about 80 abortions a week and that “a good one-third of our cases are referred by physicians.” Fees, which range from $150 to $350, include lab work, counseling, pre-operative pelvic examination, the procedure, lie-down and sit-up recovery, a prescription for medication, a post-procedure pelvic exam, and birth control information. Fees must be paid in cash, money orders, or travelers checks (this is the case for most Texas clinics).

Other Dallas facilities include Reproductive Services, a non-profit clinic, and Curtis Boyd and Associates. Dr. Boyd is a private physician who has long been interested in the abortion question and previously worked in New Mexico.

Houston is probably the most “progressive” city in the state as far as availability of abortion is concerned. Including the Jeff Davis clinic, which is for district eligible patients only, Houston has five clinics. Mrs. Billie Broch, director of Planned Parenthood of Houston’s clinic, says that the situation in Houston is changing fairly rapidly. The Planned Parenthood clinic offers vacuum aspirations for women who are not past the 8th week of pregnancy. The cost is $145, and in a limited number of cases financing arrangements can be made.

Besides Planned Parenthood, Houston has Reproductive Services, Cullen Women’s Center, Southwest Women’s Center, and the Jeff Davis clinic. Southwest Women’s Center, which is run by a group of private physicians, has been dubbed “the River Oaks of abortion clinics.” The luxury clinic will perform vacuum aspirations up to 12 weeks for $265—the highest fee for this procedure in the state. “They give beautiful care,” says Mrs. Broch. Cullen Women’s Center is the only Houston clinic where a woman can have an abortion past 12 weeks; here the limit is 20 weeks. Fees are in line with those across the state.

In San Antonio, Reproductive Services does menstrual extractions and abortions up to 10 weeks for a fee of $150. Dr. Foster Moore, the medical director of the clinic, is another Texas physician who has worked for abortion reform. At Bexar County Hospital, abortions are done up to 20 weeks. For late abortions, the hospital is using a new procedure called urea amniocentesis: amniotic fluid is removed from the uterus and replaced with an equal amount of hypertonic urea solution. Fees are higher at Bexar County Hospital since there is a hospital charge. For a vacuum aspiration, for example, the cost is $125 for the doctor and $119.60 for the hospital; for urea induction, the cost is $175 for the doctor and $175 for the hospital. Medicaid and private insurance are accepted.

Insurance

Abortion insurance presents a problem. Most clinics demand cash in advance. Medicaid and CHAMPUS (military dependents’ medical insurance) do cover abortion, but not all clinics accept it—some will have the patient pay cash at the time of the procedure and then help her file a claim for compensation later. At the Texas State Board of Insurance, a spokesman said “as a general rule, abortion is not mentioned at all” in insurance policies. If a woman can get coverage, it usually is under the maternity benefits section of the policy—to get these benefits, the woman must sign up nine months in advance of the time when she wishes to use it. This leaves a lot of women out in the cold. Occasionally, sympathetic secretaries in doctors’ offices will write “miscarriage,” or “D&C” instead of “abortion” on the claim form.

Women

Black, white, chicana, young, old, working, not working, married, unmarried—there are lots of different kinds of women. Most of them can become pregnant and most do at some time or another. Most are happy at the thought of having a child, but for a woman who is pregnant and doesn’t want to be, a pregnancy can be one of the most devastating events of her life.

For a woman facing an unwanted pregnancy, questions about laws, or attitudes, or facilities are secondary. So are lectures about birth control, morals, and what the neighbors will think. For this woman, the prime question is “What am I going to do?” She needs help and she needs it fast—an unwanted pregnancy is an emergency.

The Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics does not keep information on how many abortions are done in this state each year. If they did, the number would probably be larger than most people think. The only available statistics are estimates from private clinics and counseling services. In Austin, it is estimated that at least 1500 women seek abortions each year. In Houston, a source at Planned Parenthood said that as many as 4000 abortions have been done in that city since Spring, 1973. Planned Family Clinic in Dallas is doing an average of 80 abortions a week—that’s 4160 a year for one clinic.

Who seeks abortions? Texans involved in helping women with problem pregnancies will tell you that most are between the ages of 18 and 25, but that the range is from 12 to 40 years old. They are from all walks of life. Most are white, but blacks and chicanas are looking more toward the legal abortionist as the service becomes available. If you’re interested in astrology, the People’s Free Clinic in Austin has found that more Scorpios come for problem pregnancy counseling than any other sign. More seriously, about half the women with problem pregnancies were not using any form of birth control at the time they became pregnant. Reasons for this vary—the most frequent one is ignorance. Sometimes, women become pregnant when their physicians are changing them from one form of birth control medication to another. Other women just weren’t using effective methods.

Not all women choose abortion. A woman who has no regard at all for the life of her child is hard to find. The decision to end a pregnancy or to give a child up for adoption is influenced by love for the child, not merely love for self. There are alternatives to abortion. Women may choose to keep the child or to give it up to an adoption agency. While this is not as frequent a practice as it once was, good maternity homes such as the Edna Gladney Home in Fort Worth report that they have not experienced much of a drop in occupancy since the Supreme Court ruling was handed down. Other “homes” are experiencing drops, but are still in business.

No matter how difficult it may be to obtain an abortion, the decision and the responsibility rest with the woman. She must choose. She must seek help. She must bear the final responsibility. She must remember.

The Future

Despite the Supreme Court ruling, the fight between those who favor abortion and those who oppose it is still raging. The latter groups are more organized and better financed. Texas Right to Life, a statewide, anti-abortion, anti-euthanasia organization, was organized last summer. Right to Life groups in Dallas and Houston have been active for some time. Dr. Joseph Witherspoon, professor of law at The University of Texas School of Law, is state president of the organization. He also is one of the principal authors of the “Right to Life” amendment (sponsored by Senator James Buckley, Conservative, N.Y.) which is being pushed for adoption as an amendment to the United States Constitution.

Right to Life regards itself as pro-life rather than anti-abortion. Mary Jane Phelps, executive director of the organization, says that regardless of the fact that the Supreme Court decision “constitutes a danger to all life,” a reverence for life is essential. Phelps says that abortion is a quick negative response to a pregnancy and that women should realize that undergoing an abortion is absolute degradation, an effort to conceal the fact that they are able to have children—and thus are women in the most important sense.

Right to Life, and Birthright, a similar group, lobby for reversal of the Supreme Court decision on the national level and for restriction of abortion availability on the state level. The group is famous for its literature, which is copiously illustrated with color pictures of aborted fetuses. The Right to Life office is crammed with stacks of brochures, newsletters, “Circle of Life” bracelets (which are to be worn until the Supreme Court decision is reversed), and anti-abortion posters. The literature ranges from simple newsletters—one of which proclaims Right to Lifers are not “fetus freaks”—to elaborate brochures. In one issue of the National Right to Life News, the reader will find that he can send for “photo-postcards of aborted babies (to send to legislators) 10/$1, 25/$2, 500/$20.”

Right to Life gets a lot of criticism for this kind of literature—which physicians have called “inflammatory” and “exaggerated.” The group’s response is that people must be made aware of the reality of abortion, and it is true that the results of a salting out procedure are ugly. Pro-abortion groups counter with the fact that the results of procedures done by illegal abortionists are just as ugly, and that, too, is true. So in order to argue the question on a more rational basis, Right to Life says that the Supreme Court decision to allow abortions is a foot in the door for more sweeping decisions which will allow euthanasia and genocide.

“Despite the Supreme Court ruling, the fight between those who favor abortion and those who oppose it is still raging.”

Pro-abortion groups in Texas are not nearly as well organized as the opposition. The only formal committee is Texas Citizens for Abortion Education, a Dallas-based lobbying group which is working to keep the Roe v. Wade decision in effect. Virginia B. Whitehill, state coordinator for TCAE, says that the group’s work is aimed mainly at the federal level right now. She feels that there is a definite possibility that abortion will be outlawed again or that so many restrictions will be placed on the procedure that the decision will be negated. As examples of legislation she feels is threatening, Whitehill points out that a rider on the U.S. foreign aid bill which recently passed the Senate forbids U.S. birth control agencies in other countries to give counselor aid to women seeking abortion. The definition of “abortion” in that bill, says Whitehill, includes the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs)—a principal tool of family planning agencies in underdeveloped countries.

She also claims that groups like Right to Life are financed by the Roman Catholic Church—although evidence is not clear. Whitehill says the black genocide uproar and the publicity surrounding the case of the two young girls who were sterilized in Alabama were stirred up by anti-abortion groups.

Whitehill has been working for birth control services for women for a long time. “I used to sneak into Parkland with a typewriter,” says Whitehill, “and get a list of all the women who had had children recently so I could send them birth control information. Ed Maher, the head of the Dallas hospital district, would not discuss birth control with us—he told us birth control had nothing to do with health.”

Representative Sarah Weddington of Austin also feels that there is a danger of the decision being reversed or its impact diluted. “I feel discouraged that the decision isn’t being carried out after we went through the Supreme Court fight,” she says. Weddington feels that there certainly will be anti-abortion amendments and bills offered at the Constitutional Convention and during the next session of the Legislature, but doesn’t think it would be advisable for pro-abortion forces to offer any new bills or amendments. Instead, she would prefer that the state remain neutral. If pro-abortion bills were offered, they might only serve to make the situation worse because of the chance of amendment. “Right now, I’m fighting a holding action,” says the attorney.

There is evidence for the qualms expressed by Whitehill and Weddington. Anti-abortion forces are working for the U.S. Constitutional amendment, and simultaneously working to pass regulatory legislation limiting the effects of the Supreme Court decision. Family planning clinics funded by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) are not allowed to do abortion referral. A bill sponsored by Senator James Buckley just came out of a U.S. Senate committee and would forbid use of Medicaid money to pay for abortion, even to save the life of the mother. Anti-abortion forces are bombarding state and national legislators with literature on the subject. A Fort Worth woman says that when she wrote a pro-abortion letter to a Texas legislator, she received a whole packet of anti-abortion material in return. All Baptist ministers in the state have been sent packets of such material.

In America in March 1974, abortion is still a legal alternative for a woman who decides to terminate her pregnancy. It is not a universally available alternative in Texas, and the possibility exists that it will become less so. The issue is highly charged with emotion. On one side it is argued that the only person who should decide whether or not to choose abortion is the pregnant woman; on the other, it is argued that no one should ever have this choice.

The reality of the abortion issue is that the choice of the pregnant woman to have an abortion has an extended impact: on doctors; on hospitals and their staffs; on the father; and, depending on your point of view, on an unborn human being. The state may become legally involved through its legislators.

The certainty of the abortion issue is that, while a woman’s decision to have an abortion affects many other segments of society, the reverse is not necessarily true. The only influence that society can have on a woman who wants an abortion is whether it will be legal or illegal. Women who are desperate will find a way. Jan did. So will others.

Elizabeth is married to an attorney who practices law in a small town and they have two sons in college. When she found herself pregnant, Elizabeth and her husband decided on an abortion.

“I’m 42. If I had a baby now, I’d be 60 when it would be 18. It’s hard enough trying to understand my teenage kids now and I’d hate to think what it would be like in 20 years.

“Our boys are almost grown now, you know? I mean Bill and I had planned to do some traveling, and I wanted to start teaching again—I had to quit when John (the oldest child) was born. Well, anyhow, we had planned all these things and then I got pregnant. I think I knew right away, but I didn’t tell anyone, not even Bill. All these things were going through my head. We’d have to convert the guest room back into a nursery. I’d have to give up my idea about going back to work, it might mean Bill would have to put off retiring and then I’d read that children born to older parents had a bigger chance of being deformed or sick or something and I didn’t even want to think about that.

“It all sounds so selfish when I say it now, and I admit I still feel guilty, but I just didn’t want another baby. Instead of being happy about it, it just seemed like my whole world was crashing down. What kind of mother would I be feeling like that?

“I really hadn’t ever thought of abortion—not for myself at least. It’s o.k. for a 16-year-old girl who gets in trouble or something, but for me? I couldn’t talk to our doctor. We live in a small town and I know his wife—it’s just not like living in Houston or somewhere where nobody knows you.

“So I finally told Bill that I thought I was pregnant. He wasn’t happy about it. Oh, he tried, but I knew what he was thinking. At first I didn’t mention what I’d been thinking—about an abortion, I mean. But one night—he could tell something was bothering me—and I guess I just let it all out. We talked for a long time and decided we’d try to find somewhere. We were both relieved I think when the decision was finally made.

“So one weekend, we went to Austin. Bill had asked around and found a place where they could help us. We talked with a minister, both of us, and he was really sympathetic. He didn’t try to make me change my mind or anything and he really made us both feel better about what we were doing. So he set up an appointment for me in San Antonio. Bill went with me and it was all over in no time. Right at first, I was almost euphoric, it was such a relief. Then, when we went home and I was by myself, I began to think about it and believe me, it wasn’t easy for awhile there.

“But I still feel like I did the right thing. I can talk about it now and Bill has just been great. We never did tell the kids. Maybe someday we will, but not now. It’s changed me some, I guess. I’m more determined about going back to work and really making something of myself. I feel like I have a responsibility to do that now. I know some people would really look down on us for what we did, but it doesn’t bother me anymore. For us, it was the right thing to do.”

Jennifer is a student at The University of Texas. She transferred there from a small West Texas college after she had an out-of-state abortion. Many women from smaller Texas towns still go out of state for abortions because there are no facilities nearby, or because they just don’t want to take the chance of meeting someone they know.

“I never even considered having a baby. The guy I was going with sure as hell wasn’t any help—when I told him, he made tracks right out of town. I had a friend who’d gone to New York and she helped me get it arranged. Some of the girls in the dorm put up money—it was really great, and I didn’t have to tell my parents. So, anyhow, there wasn’t a money problem.

“In New York, they had it all set up, but I really felt herded through. Like when I was there, there were 26 other girls. They had appointments scheduled for 7 a.m. and for 11 and they took about 15 of us at a time. And this was like an everyday thing and I had no idea it would be like that. I was just floored. The whole time I was in the office, the phone was ringing and they were making appointments.

“When I got back, I told my parents I wanted to switch schools and I came down here. I take the pill now all the time, but I don’t see myself as somebody who just sleeps around. I think a lot of people won’t take the pill because it’s like admitting to yourself that you might go to bed with anyone you go out with or something. You know, like one-night stands. Well the truth is that it can happen and it’s a whole lot better to risk the side effects of the pill than to get pregnant. I’m just making sure that it never happens to me again, until I get married, I mean. I just wish more girls would face up to this kind of thing. Then, maybe we wouldn’t have to have abortions at all.”

Gwen is 20 now. She and her husband both work and their 3-year-old son is doing well. Although she could have had an abortion, she chose to have the child. She sees marriage as a valid choice for a woman with a problem pregnancy, but doesn’t advocate it in all cases.

“My parents were really great when I got pregnant. I told them we had decided to get married and Dad just said ‘welcome to the family’ to Mike.

“I really wanted to get married and have the baby. Not everyone wanted me to. My doctor even said, ‘Are you sure that this is what you want to do?’ He talked to me about abortion, but I just wanted the baby. While I was pregnant, I was really happy, but when the baby came, I realized I really had two babies on my hands.

“For a while, I think I even hated both of them. The first time I tried to dress Shawn, he screamed and screamed. Then Mike picked him up and he stopped. I just cried my eyes out.

“This went on for about two years. I don’t think I was really happy for any of that time. I finally realized I needed help when it began to show up in Shawn. He’d say, ‘Mommy, you sure do cry a lot.’ That’s when I went to get counseling.

“I have a job now and Mike is working too. I think I’d like to be a social worker. Having a baby just isn’t for everyone. We’d like to have more children someday. I wish there were a reversible vasectomy, because I don’t think I’d be happy if I got pregnant right now. But maybe in a few years when Shawn is in school, we’d like to have another baby.

“I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t come for counseling. Maybe Mike and I would have gotten divorced, I don’t know. But everything’s o.k. now. Shawn’s getting to be lots of fun. I’m glad he’s here.”

Hospital Policies

Hospitals do not have to allow abortions to be performed in their facilities; no hospital personnel may be required to perform or assist with an abortion against his or her will. The decision about whether or not to allow abortions in each facility is left up to that institution’s governing board and medical staff. These groups make the policy and decide whether or not to allow the procedure, when, where, by whom, how, and so forth.

Texas Monthly asked 46 hospitals in urban areas of the state for their policies regarding abortion. Of these, 19 replied. In general, hospitals which allow abortion require that it be an inpatient procedure and that additional consent forms (consent of the husband, or in the case of a minor, of the parents or guardian) be obtained.

Here are the policies of responding hospitals.

Austin

Brackenridge Hospital: General city hospital, 344 beds. Although Brackenridge did not reply to inquiries, abortions are being done here by private physicians using donated equipment. Medicaid patients have a hard time getting abortions here unless a private physician will take their case.

Seton Hospital: General, Roman Catholic, 152 beds. Abortions are not performed at any Roman Catholic hospital. Seton’s board of directors states: “We are opposed to abortion and will not participate in nor permit any deliberate medical procedure, the purpose of which is to deprive an individual of his right to life.”

Shoal Creek Hospital: General, corporation, 200 beds. Shoal Creek does not have facilities for performing abortions, says administrator William S. Dyer. He says a policy will be adopted “if and when” facilities are available.

St. David’s Community Hospital: General, non-profit, non-church, 267 beds. Executive Director Robert B. Lloyd calls abortion a “socio-economic problem,” and says that St. David’s allows no “convenience” abortions. Therapeutic abortions are allowed with “qualified consultation.”

Dallas

Baylor University Medical Center: General, Baptist, 1125 beds. “Certain specialists” may perform abortions during the first 12 weeks. “The patient’s decision for this procedure will be only one factor in the determination,” according to a Baylor news release. In addition, her physician must agree and must obtain one consultation with a Baylor staff physician. Termination after the first 12 weeks is done only for therapeutic reasons.

St. Paul Hospital: General, Roman Catholic, 489 beds. Adheres to the standard Roman Catholic right to life policy. St. Paul’s sometimes sponsors seminars on alternatives to abortion.

El Paso

Hotel Dieu Hospital: General, Catholic, 284. No abortions allowed.

Newark United Methodist Hospital: Maternity, Methodist, 31 beds. “Our staff has avoided a firm position in this matter . . . We would prefer that our facilities not be used for this purpose unless a medical necessity is indicated,” says administrator James H. Speer.

Providence Memorial Hospital: General, non-profit, non-church, 436 beds. Allows abortions, with no restrictions, up to 5 months of pregnancy. All procedures are done on an inpatient basis. ‘‘In accordance with Texas State law,” says Administrator Ross F. Swall, “a fetus weighing 500 grams and measuring 28 centimeters in length is turned over to a mortuary for burial.”

Fort Worth

All Saints Episcopal Hospital of Fort Worth: General, Episcopal, 431 beds. Administrator Carl S. Jackson says the hospital “has no formal policy specifically regarding abortions.” The procedure apparently is allowed as long as the doctor obtains a consultation from a member of the active or consulting medical staff.

Duncan Memorial Hospital: Maternity, non-profit, non-church, 19 beds; associated with The Edna Gladney Home. No abortions, since this hospital is associated with a maternity home. However, The Edna Gladney Home is a good alternative for women who want to give up their children for adoption, or keep the child on their own. Pleasant surroundings, good care, counseling. Write Mrs. Ruby Lee Peister, executive director, 2110 Hemphill Street, Ft. Worth, 76110.

Harris Hospital: General, Methodist, 611 beds. Abortions are allowed, but the hospital does not wish to publish its policies.

Saint Joseph Hospital: General, Roman Catholic, 500 beds. Adheres to the right to life statement of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word.

Tarrant County Hospital District: John Peter Smith Hospital, general, hospital district, 214 beds. Abortions are allowed with consent of the patient and her physician during the first trimester. Later abortions require consultation. Counseling and consent forms are required.

Houston

Harris County Hospital District: Jefferson Davis Hospital, maternity, hospital district, 266 beds. Abortions up to 12 weeks allowed with consent of patient and physician. Afterwards, consultation is required and abortions may be performed “solely for medical, surgical, or psychiatric indications.” District eligible patients only.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital: General, non-profit, non-church, 738 beds. Abortions are allowed, but the hospital does not wish to publish its policies.

Memorial Hospital System: General, non-profit, non-church, 1001 beds. Abortions during first trimester with consent of patient and physician. Later abortions require consultation and approval of the Therapeutic Abortion Committee.

San Antonio

Bexar County Hospital District: See “Where to get help,” p. 64.

Lutheran General Hospital: General, Lutheran, 183 beds. Allows abortions during the first trimester after consultation with a staff ob-gyn physician. Also requires consultation with a social worker, a chaplain, and a psychiatrist under certain circumstances. Two ob-gyn consults are required after the first trimester and the abortion must have “therapeutic justification.” After 24 weeks, a therapeutic abortion requires the prior approval of the Ob-Gyn Policy Committee.

Metropolitan General Hospital: General, corporation, 250 beds. Permits therapeutic abortions only with the consent of 2 disinterested consultants, plus the attending surgeon. “We do not honor ‘demand’ abortions,” says the administrator.

Santa Rosa Medical Center: General, Roman Catholic, 1009 beds. Adheres to the right to life statement of the Sisters of Charity of the IncarnateWord.

Southwest Texas Methodist Hospital: General, church, 400 beds. Allows abortions during the first trimester with consent of patient and physician.

The Procedure

If abortion is chosen as an alternative to pregnancy, the procedure should be done as soon as possible—ideally, during the first 12 weeks. During this period, vacuum aspiration is the usual method. Statisticians report that this procedure is three times safer than a tonsillectomy and five times safer than normal childbirth. While pregnancies can be legally terminated up to the 24th week, procedures used become increasingly dangerous for the woman; they are also more expensive and more difficult to obtain. Procedures most commonly used are:

Endometrial Aspiration

Sometimes called “menstrual extraction,” endometrial aspiration is a relatively new procedure for women who have missed a menstrual period by no more than 12 days, calculated from the first day the period should have begun. Doctors generally prefer to wait until the eighth day to do the procedure.

Similar to the vacuum aspiration method, endometrial aspiration is accomplished by inserting a flexible plastic tube called a cannula into the uterus. Using suction, the contents of the uterus are gently removed. Anesthesia is optional and the cervix is usually not dilated. Endometrial aspiration is done on an outpatient basis; costs range from $50 to $125.

Vacuum Aspiration

Vacuum aspiration is the most common method of ending a pregnancy up to 12 weeks. It is safe and relatively painless—a woman may have some pain which feels like menstrual cramps; for some women, it will hurt a bit more, but this is unusual.

With this procedure, a cannula slightly larger than the one used for endometrial aspiration is used. A local anesthetic (paracervical block) is injected around the uterine cervix, and a gradual enlargement, or dilation, of the cervical opening is done using metal dilators. A newer and safer method of dilating the cervix is done by the insertion of sterile seaweed into the cervix. These small blocks of seaweed look like matchsticks. After insertion, the material absorbs fluid and expands, gradually dilating the cervix over a period of about six hours. This method of dilation is preferable because metal dilators may sometimes damage cervical tissues.

After the cervix is dilated, the cannula is inserted into the uterine cavity. Vacuum suction removes the fetal material from the wall of the uterus and out into a collection bottle. Then the uterine lining is checked with a curette (a long metal instrument with a spoon-shaped end) to make sure that all fetal tissue has been removed. The suction procedure lasts from 5 to 10 minutes.

Afterwards, the woman will probably feel well within an hour or two. Normally, she can return to work or school the next day, but she should avoid strenuous exercise for a couple of days.

Vacuum aspiration is usually done on an outpatient basis. The cost is about $150.

Dilation and Curettage (D&C)

Until the recent development of vacuum aspiration technique, this was the standard abortion procedure up to 12 weeks. It is also standard gynecological practice for other reasons, such as clearing the womb after miscarriage or attempting to remedy certain causes of infertility. D&C is still fairly commonly used as an abortion method by physicians who do not have access to vacuum equipment.

A general anesthetic is used. The cervix is dilated, and a curette is inserted and used to gently scrape the uterine wall to dislodge the fetal and placental material, which is then removed from the uterus with forceps.

D&C for abortion purposes has proved safe as an office procedure in most cases, if emergency care and follow-up check are available.

Repeated curettage of the uterine wall can lead to buildup of scar tissue which impairs the ability of the uterus to expand in pregnancy.

Dilation and Curettage in Combination With Vacuum Aspiration

This procedure must be done in a hospital. It is not a common one, but is sometimes used to terminate pregnancies between 12 and 14 weeks.

A general anesthetic is used and the cervix is dilated by use of metal rods or seaweed. Ring forceps (a long scissor-handled instrument with metal rings at the end) are inserted into the uterus and are used alternately with the cannula and vacuum suction to remove fetal and placental material. The uterine lining is then checked with a curette to make sure all fetal material has been removed.

An overnight hospital stay may be required and costs may be twice that of a simple vacuum aspitation.

Saline Injection

Saline injection, also called “salting out,” is performed from 16 to 24 weeks (the legal limit for voluntary pregnancy termination). At least an overnight hospital stay is required.

To do a saline injection, the doctor anesthetizes an area of the abdomen and inserts a long needle through the abdomen into the uterine cavity. Some of the amniotic fluid is removed and replaced with an equal amount of a strong, sterile salt solution. This induces labor (contraction of the uterus) and within 24 to 48 hours, the fetus is expelled. Sometimes, it takes longer for the fetus to be expelled. A follow-up curettement (D&C) may be required to remove retained placental fragments which might cause infection.

By the beginning of the second trimester (about 13 weeks), the fetus looks definitely human; the emotional impact of salting out is greater and many physicians prefer not to perform this procedure, although it is done at some clinics. The cost ranges up to $450.

Uterine Induction

Done for pregnancies which are between 15 and 19 weeks, uterine induction is similar to saline injection. A catheter is inserted into the uterus and an enzyme called prostaglandin F2 is injected. The uterus will begin to contract after about 18 hours and the fetus and placenta are expelled. Usually, a follow-up D&C is performed.

The cost for uterine induction is about the same as for a saline instillation. A hospital stay is required.

Hysterotomy

Hysterotomies are used after 16 weeks and only in cases where saline instillation or uterine induction is contraindicated. A hysterotomy is equivalent to a Caesarean section—it is major surgery requiring a hospital stay of several days and requiring general anesthesia.

An incision is made in the lower abdomen and a second incision is made in the uterine wall. The fetus and placental material are removed and the incisions are closed.

A hysterotomy can cost up to $1200. Future births must be by Caesarean section.

Complications

If an abortion is done during the early weeks of pregnancy, and if the procedure is medically supervised, complications seldom develop. The later in pregnancy the abortion is performed, the more complications are likely to occur.

Infection is the most frequent complication. A statistically lesser risk is hemorrhage or perforation of the uterus; in case of the latter, hospitalization is required. Serious complications occur at the rate of three or four per 1000 medically supervised abortions.

Repeated abortions may also be dangerous. Repeated forceful dilation of the cervix may lead to cervical incompetence, a condition in which premature spontaneous dilation of the cervical opening in pregnancy results in miscarriage. Repeated curettage of the uterine wall can also impair the ability of the uterus to carry a pregnancy to term. There is no agreement on how many abortions constitute a danger to future pregnancies.

Abortion not supervised by a licensed physician is extremely risky. Untreated infection of the uterus or uterine hemorrhage can quickly lead to death.

Where to Get Help

A woman who has a problem pregnancy has several alternatives from which to choose: carrying the child to term and giving it up for adoption; keeping the child either alone or with a partner; and abortion. All Texas cities have facilities where a woman can get help. It is always advisable to go to a counselor who can help one make the decision. Reliable places in most Texas cities are Planned Parenthood and Clergy Consultation. In some towns, like Dallas and Houston, Right to Life groups are geared to help the pregnant woman who does not choose abortion. It is not usually advisable to call numbers listed on billboards along freeways; often, these “services” are referral agencies which charge as much as $50 to tell a woman something she can find in the telephone book.

Austin

There are no outpatient abortion clinics in Austin. There are several counseling agencies and one maternity home. If you need help call:

The People’s Free Clinic, at the Congregational Church, 408 W. 23rd, 478-1746: Pregnancy tests, problem pregnancy counseling, referral. Treatment is free if you don’t have any money.

Vickki & Jane, 454-1795: A telephone service for women who need help regarding pregnancy, rape, and VD. Vickki & Jane volunteers are women who have had problem pregnancies and who can give you information on all alternatives to problem pregnancy. They will counsel with women by phone 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and will refer them to agencies which can help. Vickki & Jane hopes to go statewide by this summer.

Clergy Consultation, 474-5321: Problem pregnancy counseling and referral by a group of Austin ministers who volunteer their time. The service is non-denominational.

Women’s Problem Pregnancy Counseling, 2434 Guadalupe, 478-0452 (if no answer, 472-9246): Problem pregnancy counseling and referral by a women’s group.

Model Cities Family Planning Clinic, 1601 E. 6th, 474-1526: Problem pregnancy counseling and family planning services for residents of the Model Cities area. No abortion referral. Clients must have a Brackenridge clinic card.

Home of the Holy Infancy, 510 W. 26th, 472-9251: Residential maternity home run by the Roman Catholic Church. Children given up for adoption are sent to Roman Catholic families.

Dallas

Clergy Consultation, 691-1282: Clergy group similar to Austin’s. There is a nominal fee for counseling.

Birthright, 691-8881: Counseling and referral for alternatives other than abortion.

Planned Family Clinic, Inc., M-2055 Campbell Centre, 8350 N. Central Expressway, 692-1022: Commercial abortion clinic. Abortions up to 19 weeks. Prices range up to $350. Call for appointment.

Reproductive Services, Inc., 2339 Inwood, Suite 37, 350-7026: Non-profit abortion clinic. Abortions up to 10 weeks. Bring proof of pregnancy. $150.

Dr. Curtis Boyd and Associates, 2921 Fairmont, 742-9310: Private clinic run by physician. 12-week pregnancy limit. $150. Call for appointment.

El Paso

There are no private abortion clinics in El Paso. Abortions can be done by private physicians at Providence Hospital.

Planned Parenthood, 542-1919: A reliable source of information on problem pregnancies and family planning.

Booth Memorial Home, 3918 Bliss Ave., 565-4638: A residential maternity home. A special feature at Booth is a program which allows the woman who wishes to keep her child to continue living there with her child up to two years. During this time, the woman will learn to care for the child and can finish school, get job training, and so forth.

Fort Worth

There are no private abortion clinics in Fort Worth, but women who choose abortion can go either to their private physicians or to one of the clinics in Dallas. A good source of information is Planned Parenthood, 332-9101.

The Edna Gladney Home, 2110 Hemphill, 926-3304: One of the best residential maternity homes in the state. Counseling, educational services and high standards.

Catholic Social Services, 921-3023: Counseling are referral for alternatives other than abortion.

Houston

Planned Parenthood of Houston, 3601 Fannin, 522-3976: Both an abortion clinic and a counseling service. Vacuum aspiration up to 8 weeks, pregnancy tests, birth control information, follow-up care. Abortions are priced at $145.

Cullen Women’s Center, 7443 Cullen, 733-9391: Abortions up to 20 weeks, all tests, some counseling. No appointment necessary for pregnancy tests between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday. Prices start around $145.

Southwest Women’s Center, 6565 DeMoss, 771-0611: Abortions up to 12 weeks. “The River Oaks of abortion clinics” charges $265 for complete vacuum aspiration procedure. Care is said to be excellent.

Villa Maria Center, 119 Lovett Blvd., 526-4611: Sponsored by Catholic Community Services, Villa Maria is a residential maternity home which also provides care on an outpatient basis.

Florence Crittenden Home, 5107 Scotland, 869-7221: Formerly housed in a 40-year-old firetrap of a building, the Florence Crittenden home has a brand new building for residential maternity care. The 46-bed facility has some extra space which the board is thinking of devoting to care of non-pregnant women who need help. Facilities are very nice, but there’s no swimming pool.

Birthright, 529-7273: Counseling and referral for alternatives other than abortion.

San Antonio

Reproductive Services, 48 10 San Pedro, 826-6336: Menstrual extraction, vacuum aspiration up to 12 weeks. Cost around $150. Call for appointment and check the address—this clinic has a reputation for moving around.

Bexar County Hospital, 696-5007: Abortions up to 20 weeks. Hospital charges are added to procedure charges, making the cost about double that of private clinics. Accepts medicaid, health insurance.

Planned Parenthood of San Antonio, 224-6163 : Counseling and referral.

Methodist Mission Home, 696-2410: Residential maternity home run by the Methodist Church. You do not have to be a Methodist.

Prenatal Development

First two weeks:

Zygote goes through multiple cell divisions. It attaches itself to the uterine wall, becoming an embryo, a fish-like organism floating in a fluid filled sac.

Fourth week,

Primitive heart begins beating, cannot be detected, though; rudimentary organs begin to form; the organism still has a non-human form.

Second month:

(8 weeks)

Develops a head, with the beginnings of the facial features. Fingers, toes, ears and eyes begin to form. Approximately 7/8 inch long and weighs approximately 1/30th of an ounce.

Third month:

(12 weeks)

Embryo becomes a fetus; it has a definite human appearance and is already active; almost all internal and external physical equipment is developed. It is now over 3 inches long.

Fourth month,

(16 weeks)

Growth of lower body parts accelerates; most bone models formed; mother feels “quickening”; sex can be observed; eyelids, lashes, eyebrows, toenails, and teeth developed. Approximately 7 inches long and weighs approximately four ounces.

Fifth month:

(20 weeks)

Fetus sleeps and wakes; it has a characteristic “lie”; fetal heartbeat can be heard; it is capable of extra-uterine life, except that its lungs are not sufficiently developed to maintain respiration.

Seventh month:

(28 weeks)

Fetus fully developed; can survive outside of uterus in highly controlled environment.

Eighth and ninth months:

Fat forms over the body, and the finishing touches are put on the organs and functional capacities.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Health

- TM Classics

- Abortion