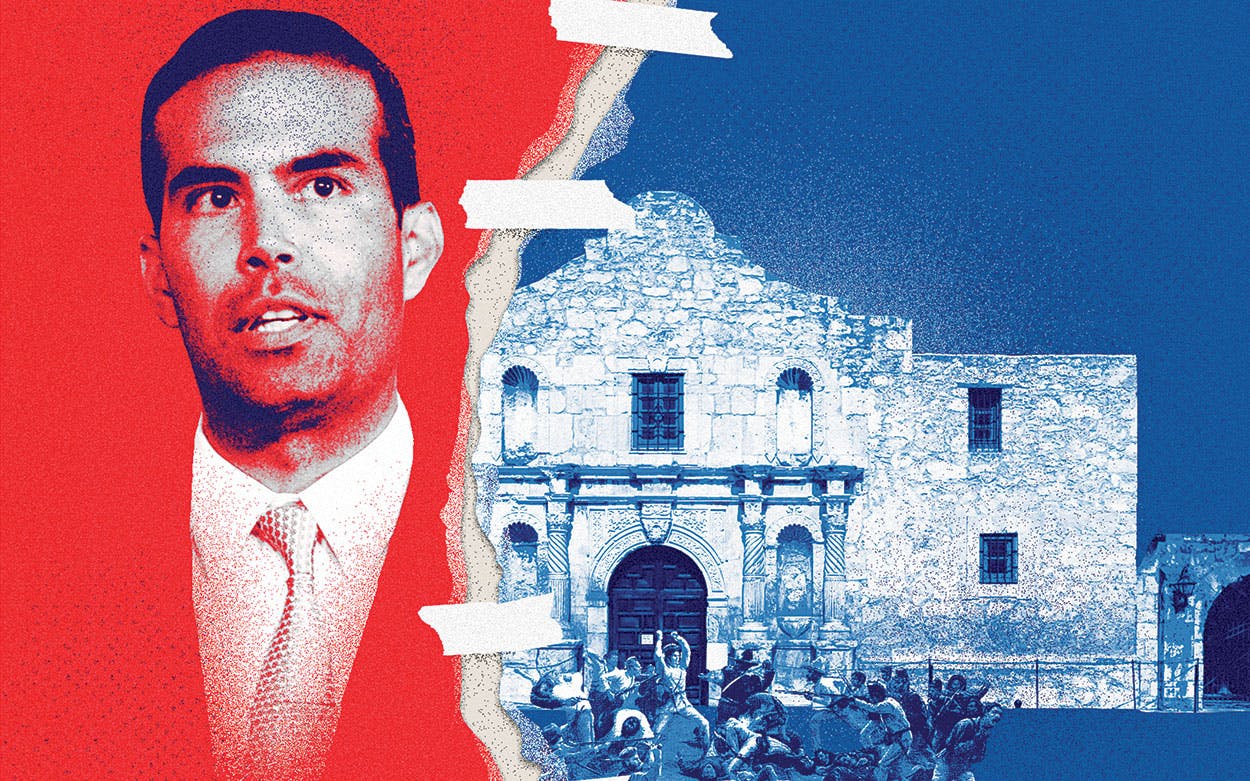

The Battle of the Alamo concluded on March 6, 1836. Nine months and two weeks later, the Congress of the Republic created the General Land Office, the oldest state agency still in existence, to manage the land Sam Houston’s men had won. They are two of the oldest totems of Texan identity there are, and these days they have the same custodian: land commissioner George P. Bush, the only member of one of the most successful political dynasties in American history who currently holds office.

When Bush ran for the office, in 2014, effectively unopposed, the Land Office seemed to suit his needs perfectly. It’s a place where it’s easy for a commissioner to leave an imprint, which is one reason why it’s consistently been used as a stepping-stone to higher office. Every land commissioner since 1971 has run for another job at the end of his time at the GLO, and everyone expected the same of Bush, the son of former Florida governor Jeb Bush. Young, handsome, and half-Hispanic, he seemed to offer something different to a Republican Party increasingly eager to diversify its voting base.

He also had, waiting for him, the perfect project for an aspiring Texas politician: fixing the Alamo. For years there had been biting criticism of the way the Daughters of the Republic of Texas managed the state’s most sacred site. In his first year in office, Bush kicked out the DRT and took full control. The GLO, working with the City of San Antonio, generated a plan to reclaim much of the original footprint of the Alamo mission by purchasing local buildings and decluttering the area. The tourist traps and the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! would go, and the Shrine of Texas Liberty would be given a more reverential setting.

But over the past few years, that redevelopment plan has backfired. While Bush has struggled to contain other problems at his agency, public discontent about his Alamo blueprint has grown from a fringe movement to a wider phenomenon, one that now includes a variety of conservative activists who’ve never had much truck with Bush anyway.

Even so, the future of the Bush dynasty still seemed secure until Jerry Patterson, a cocksure and consistently well-armed ex-Marine pilot who ran the agency from 2003 to 2015, decided in early December to challenge Bush in this year’s Republican primary, joining two other similarly discontented candidates. The absolute last place a politician wants to stand is between Texans and their national myths, and Bush’s career now depends on convincing Texas conservatives he’s one of them. He’ll find out if he’s done so when Republican primary voters cast their ballots on March 6, the 182nd anniversary of the battle.

In July 2015 Bush summoned employees of the General Land Office to an unusual meeting. Though Bush had coasted into office the year before over token opposition, it had been a rocky few months. Shortly after accepting a job as Bush’s chief of staff, Trey Newton, the consultant whom Bush had called “our Karl Rove,” left the agency under unclear circumstances, depriving Bush of his political adviser. Bush struggled with what he saw as the overly compartmentalized nature of the agency, which had been organized firmly in Patterson’s image. That summer, Bush announced what he termed an urgent “reboot” of the agency.

The GLO, Bush said in a speech to his staff, was beset by “many threats, asymmetric threats.” And the menace that troubled the agency didn’t come from outsiders. “The real threat, really, is internal,” he said. His chief clerk, Anne Idsal, took to the podium to lay out Bush’s new plan: the Land Office would become like “an agile special forces of Texas government,” she said, a “team of teams” that would “break out floors as it breaks down walls.” Staff cuts would be coming, as would salary decreases.

“The reaction to the idea that there were enemies within the agency was crippling to morale and the functioning of the agency,” said Chris Elam, a veteran state Republican party operative who worked for the GLO under both Patterson and Bush. There was clearly fat to cut, Elam said, but Bush’s use of the term “threat” was puzzling to everybody in the room. The message seemed to be that Patterson’s imprint on the agency was now a problem.

Waves of resignations and terminations followed. Disgruntled employees started leaking to the media, which produced a string of stories about trouble at the agency. There were other unforced errors; at the end of his first year, in a video conference call with supporters of his father’s unraveling presidential campaign, he regretfully noted that he was “stuck here in Texas” instead of campaigning in Iowa. He contrasted the importance of Jeb’s race with “running for dogcatcher like I did in Texas,” a remark that spread widely.

Remember the hog Carcass Storage Facility!

The Alamo hasn’t always been a place of reverence. In 1877, French businessman Honore Grenet turned the nearby long barrack into a grocery—and used the Alamo’s chapel to string up and store hog carcasses.

But Bush still had the Alamo redevelopment initiative, an opportunity to make all of that irrelevant. The principle of that plan—to turn the Alamo into a memorial worthy of the name—had wide backing, and it had to be done soon. In 2014, British singer Phil Collins, a longtime Alamo history buff, donated his haul of Alamo artifacts to the state, with the proviso that a suitable home for them be built within seven years. The new plan, unveiled last year, would approximate the original boundaries of the mission as it existed during the battle, swallowing up much of the surrounding concrete-clad Alamo Plaza, and build a gleaming new museum with a rooftop garden and nearby canals.

The Land Office brought on historical preservation experts from a Philadelphia design firm, who approached the Alamo as a historical site instead of a place of popular imagination. To many Alamo enthusiasts, like Rick Range, a retired firefighter who’s running alongside Bush and Patterson in the primary, that was the first mistake, “calling in all these out-of-state so-called experts who knew nothing about the Alamo, nothing about what it means to Texas.” Range and his friends particularly objected to the tall glass walls the designers proposed installing in the plaza to mark the footprint of the original complex, preferring instead stone walls approximating the ones the defenders used. They especially objected to the fact that the plan proposed moving the Alamo cenotaph, the marble-and-granite column that lists the names of deceased defenders, closer to where the defenders’ bodies are believed to have been burned. To some, the proposal evoked the ongoing debate about what to do about prominent Confederate memorials. Range calls Bush’s plan a “gross monstrosity,” the result of an excessively “politically correct environment,” and has labeled Bush a “carpetbagger.”

The debate over the plan sharpened, and Bush was slow to react. At a protest in October, one speaker decried Bush as part of a cabal that “want[s] to destroy our Western sense of identity.” The GLO has launched an extensive public relations campaign to counter these attacks—Range built a website at savethealamo.us; the agency built one at savethealamo.com—and courted conservative kingmakers, with mixed results. The glass wall disappeared from the plan, and the agency sought to reassure people that the cenotaph would stay in some form. In October, Bush gave a speech at the Alamo, flanked by “Come and Take It” flags—which reference the Battle of Gonzales, not the Alamo—in which he promised that “this shrine will continue to be a place where 1836 lives and breathes every single day.”

None of that was enough for protesters like Range. “He cannot be trusted with the future of the Alamo,” he said of Bush. “He’s flip-flopped more times than a catfish stranded on the bank of a river.”

Bush and Patterson’s campaigns are about as mismatched as the Texian and Mexican armies: Bush had almost $3.4 million in the bank at the end of last year, to Patterson’s $95,000. (Though Patterson had only been a declared candidate for a few weeks.) But in the past few years, the key element in the Republican primary has been the countless small town halls and candidate forums held by Republican clubs around the state, where candidates appeal directly to the grass roots. Patterson has attended more than a dozen. Bush is opting out.

When Wesley Lloyd, the president of the McLennan County Republican Club, in Waco, reached out to Bush’s campaign in December about hosting him at a candidate forum in February, a scheduler emailed back that the commissioner had scheduling conflicts, citing his involvement in Hurricane Harvey recovery efforts. “I don’t think we will be able to schedule this at this time,” she said. Lloyd’s puzzled response: “I didn’t give [the campaign] the list of potential dates.” Bush isn’t talking to the press much either; an effort to interview him for this story was declined by his campaign manager.

Outside a McDonald’s somewhere between San Antonio and Austin, while his campaign volunteers are loading up on Quarter Pounders, Patterson tells me that he regrets stepping down from the Land Office in the first place. “This agency is important to me. The people who work there are important to me,” he said. Back in 2013, Bush came to see him and said, “ ‘If you’re not gonna run for office, I’m gonna run for it,’ ” Patterson recalls. “And I said, ‘Well, he doesn’t know anything yet, but that’s fine.’ ”

Patterson regards Bush as “a very nice man” but a little undefinable. As Bush was inheriting the agency, Patterson tried to spend some time with his successor, to no avail. “I said, ‘Let’s go to lunch, let’s get a beer,’ and he never wanted to.

“My first inclination that he wasn’t gonna be a sterling leader was when he had his hundred-days press conference, and it was a press conference that the press could not attend,” Patterson said. “They had it on Periscope. That’s some kind of app or something.” Bush claimed then that he had “cleaned up contracting” at the agency. The implication that the agency had been crooked under Patterson didn’t please Patterson at all.

Patterson’s campaign literature is decked out with Alamo iconography, but he’s focusing just as much on the GLO’s response to Harvey as he is on the Alamo. The Land Office, which took some responsibility for disaster recovery efforts under Patterson, has been slow out of the gate after Harvey. (In September the GLO announced that it would help run a program to make temporary repairs to damaged homes, but by mid-December it had fixed only two homes.) Bush’s initial staff cuts included senior members of the agency’s disaster recovery team, who had had less to do after Hurricane Ike recovery efforts had wound down.

Range and Davey Edwards, a land surveyor who’s the fourth candidate in the race, are unlikely to pose a significant threat to Bush, but if they keep anyone from getting a majority, they may help Patterson force Bush into a runoff, where insurgent candidates generally do well. (Range has said he would support Patterson in a runoff.) That said, Patterson has made a lot of enemies over the years. After he came in a distant fourth in his 2014 primary race for lieutenant governor, he angered many Republicans when he sent state news media a pile of opposition research on the victor, Dan Patrick, which included medical records. It remains to be seen how many hurt feelings persist from that episode.

That is, if anyone cares to remember it at all. You can always count on Texans to go for the better story. The real source of Bush’s problems, opponents say, is that he has so far failed to understand the signs and symbols of this state—the foundation of the story—and that may now cost him everything. If George P. Bush survives, it will likely be because sometime in the next few weeks he learns something important about telling his own story.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Jerry Patterson

- George P. Bush

- San Antonio