On a bright Saturday afternoon on West Sixth Street in Austin, seven women perch on the saddles of a PubCrawler, one of the unwieldy pedal-powered party bikes that have become ubiquitous downtown. Six of them wear matching black tank tops with “#courtneysATXbash” emblazoned in glittery golden script; the titular Courtney wears the same design in white. Paused at a red light, they sip Michelob Ultra and canned rosé and pose for perfectly angled selfies. The nineties R&B classic “No Scrubs” begins to pulse from the PubCrawler’s speakers. “Yaaas!” one of the women cries. “I am ready for some throwbacks!”

Tom, the party’s affably tolerant guide charged with steering the contraption, clangs a bell and points to the traffic light—everyone was too distracted to see it had turned green. “Pedal, bitches!” a member of #courtneysATXbash commands.

The biking is surprisingly strenuous—maybe it’s the added weight of the cooler of Michelob Ultra—and this isn’t the group’s only exercise for the day; they’ve already attended a pole-dancing class this morning. They inch past a group of guys in University of Texas frat gear (“Keep pedaling!” one yells) and two young girls wearing tights and leotards (“She would have been good at class today!” says a bachelorette).

Every twenty minutes or so, they disembark to enter a nonmobile drinking establishment (the Tiniest Bar in Texas, the Lavaca Street Bar, the Rustic Tap), down a round of beers, and climb back onto their ride.

At one point, they pass another PubCrawler parked outside a bar, but they don’t seem to notice. Their attention is devoted to the action within their own vehicle, where they just found out that Tom—who works as a project manager at a local tech start-up during the week—somehow doesn’t know what Beyoncé means by “watermelon” in her song “Drunk in Love” (hint: it’s better suited to the bedroom than a barbecue).

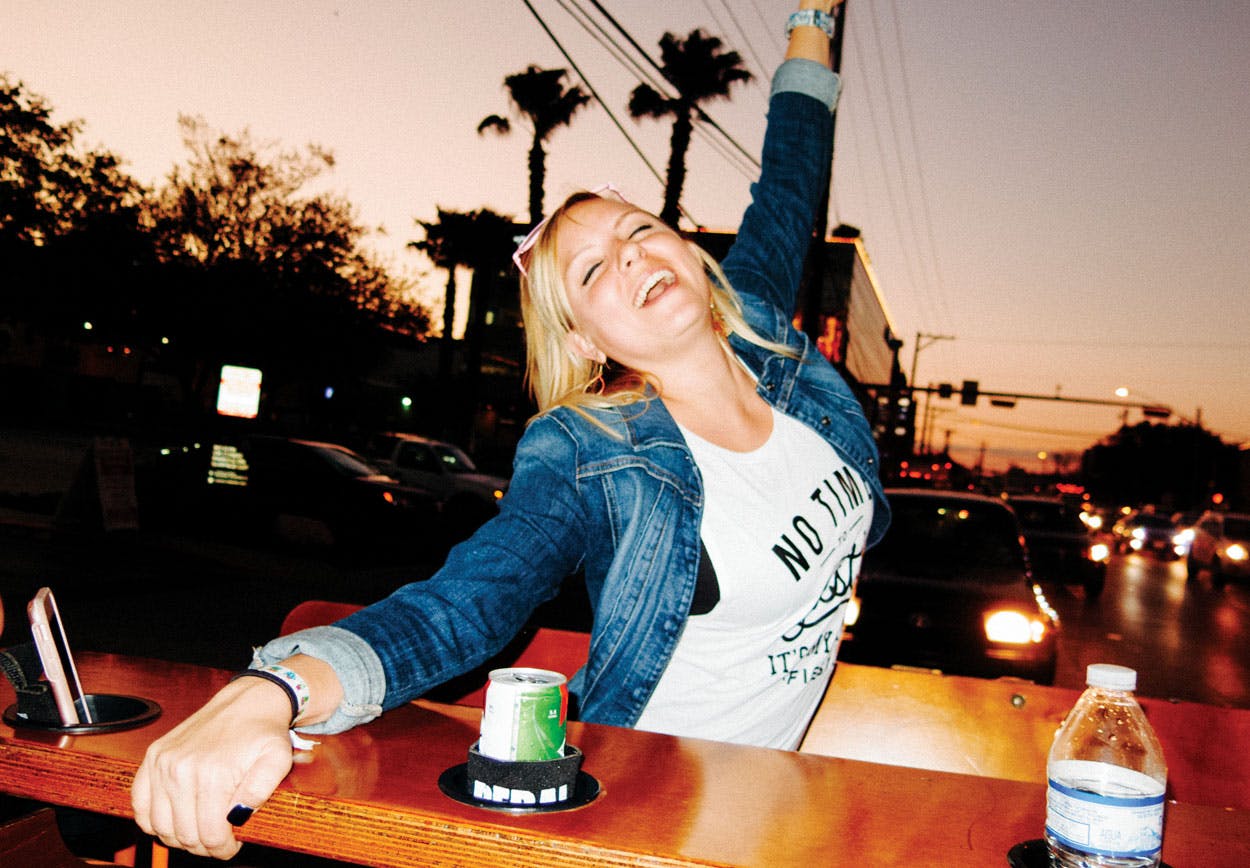

Welcome to Austin, the bachelorette capital of Texas. The canned rosé is flowing, the bass is thumping, and, ladies, it’s time to pedal.

Once known for its slacker vibe and honky-tonks, Austin consistently ranks among the top bachelorette spots in the nation. “People love the food, the music, the ambience, the local flavor,” says Ivy Jacobson, senior digital editor of The Knot, a popular wedding website. “It’s a really fun destination to go for a weekend and immerse yourself in.” As Brides magazine, WeddingWire, and countless wedding planning blogs attest, the city offers the amazing cocktails, adorable murals, and artsy vibe that the modern bride-to-be (and her six to twelve best friends) is looking for.

These women are emblematic of Austin’s recent tourism boom. They’re young, affluent, and overwhelmingly white, like many of the 110 people who move to Austin each day. They parachute in from other cities, eager to be charmed by a slower, more affordable way of life that still offers the amenities they value: beautifully plated brunches, open-floor-plan accommodations, and tastefully curated boutiques. Best of all, Austin enables them to try on a local culture made accessible and familiar: a version of the city’s identity, cropped and filtered to fit in the neat confines of a social media post. Yet as they contribute to Austin’s $8 billion tourism industry, they also threaten the affordability and identity of old neighborhoods. The bachelorettes are a case study in how the city has changed and whom the new Austin is for.

As these visitors have flocked to the city, an ecosystem of local businesses has sprung up to serve them. For the active bride tribe, there is, of course, the PubCrawler (which hosts an estimated forty bachelorette parties on a busy weekend). There’s also Vino Vinyasa Yoga, where yoga-instructors-slash-sommeliers pair cow poses with cabernets. Champagne Supply Co. can bring a twee vintage truck with champagne cocktails and sparkling wine on tap straight to the Airbnb. And then there’s Pretty Goods ATX, an online retailer that caters to bachelorettes, with customizable balloons, banners, sunglasses, and koozies (and, by special request, X-rated items like penis-shaped pool floats and water bottles). It’s enough to make an overwhelmed maid of honor long for someone to plan it all.

On a recent Friday morning, Maggie Rester pulls out her party supplies and gets to work. Inside an avocado-green townhome in East Austin, she affixes “Good Vibes” stickers to champagne bottles, inflates an enormous balloon in the shape of an engagement ring, and stocks a refrigerator with spiked seltzer (for the pregame) and Gatorade (for the morning after). After securing seven gold balloon letters to the staircase of the Airbnb, the 26-year-old pulls her blond hair back with a pink velvet scrunchie and assesses her work: F-E-Y-O-N-C-E, a portmanteau of “fiancée” and “Beyoncé,” glints back at her. She nods in approval. “The bride loves Beyoncé,” she explains. “That kind of information is great for me because I don’t know her very well. But that’s something I can work with.”

Rester is the founder and sole employee of BASH, one of several professional bachelorette party planning services in Austin. For an average of $450 per person, Rester books her clients a vacation rental or hotel, makes brunch and dinner reservations, organizes a car service for the weekend, and customizes itineraries that could include cycling classes, bottle service, boat rentals on Lake Travis, and wine tastings in Fredericksburg. “I want to show them a local’s tour, not what Yelp or Google is telling you to do,” says Rester, who grew up in Austin. “I want to eliminate the research for them.”

A few minutes after noon, the doorbell rings: the bachelorettes have arrived. Fresh from their flight from New Orleans, they ooh and aah over the cah-yoooooooooot decorations: the flashing bling rings, the “Who knows the bride best?” questionnaires, the cookies decorated with Beyoncé lyrics. Rester says her goodbyes and leaves the bachelorettes to apply their flash tats and pose in front of the balloons. But not for too long. Rainey Street is waiting.

Generations of locals, students, and weekend warriors have stumbled through the drunken mishmash of humanity that is Sixth Street in search of cheap booze. But over the past decade, nearby Rainey Street has begun to attract a more specific set: young revelers who don’t mind throwing down for cleverly named cocktails rather than cheap well drinks.

Rainey Street’s two-block stretch, just south of Cesar Chavez on the west side of I-35, boasts fifteen bars, most with their own gimmick. The circus-themed Unbarlievable has Hula-Hoops and a slide in the backyard; Container Bar is, of course, constructed of shipping containers. Bachelorettes come in droves, blanketing the street in millennial pink. Around 10 p.m. on a recent Saturday at Unbarlievable, four women, one wearing a “Bride-to-Be” sash, pin their rompers to their sides and squeal as they shoot down the slide. At Lucille, a group in matching shirts sip vodka sodas through unnervingly veiny phallic straws. Their tiara-clad bride stands a few feet away, swaying to music as she plays cornhole.

Tory Nelson, a bartender at Banger’s Sausage House & Beer Garden, estimates the restaurant serves a dozen or so bachelorette parties each weekend. At night, they come for craft brews and bratwurst; for brunch, they queue for avocado toast and something called a . . . manmosa?

“Oh, on Sundays the manmosas are a big draw,” Nelson says, leaning back in his chair at the Banger’s office. “We pour an entire bottle of sparkling wine into one of our steins—our liter mugs—and top it off with some orange juice.” A manmosa order comes with a hand stamp, which prevents people from ordering more than one a day. Luckily, down the street at Icenhauer’s, the bartenders serve a quart of sangria in a mason jar.

Nelson spends most of his days and nights amid the thriving bachelorette scene of Rainey Street. He lives at the Millennium, the latest of four apartment buildings constructed on the street since 2006. For Nelson, who spends his free time in Rainey’s drinking establishments, the proximity to bustling bars and hard partiers is an attraction, not a nuisance. “On my floor, there’s a few Airbnbs, so I see lots of bachelorette parties,” Nelson says. “I see people I’ve served before. They probably don’t remember me, but I know I’ve served them.” He and his wife, who works as a bartender at Parlor Room, across the street, don’t notice the late-night noise at home. “I could see that with some houses in some neighborhoods, neighbors would be bothered, but I don’t deal with it,” he says with a shrug. After all, when bachelorettes are loudly pregaming, he’s not home—he’s serving others like them right down the street.

Only seven years ago, Banger’s was a single-family bungalow. Most of Rainey Street, in fact, was residential—for generations it had been a quiet neighborhood of predominantly Hispanic families and businesses. But in the early aughts, as development encroached on all sides, the city changed the neighborhood’s zoning to encourage high-density development. Lustre Pearl, the first bar on Rainey, opened in 2009. (That location closed in 2014 to make way for the Millennium.) Steadily over the next few years, families sold their homes, which often—instead of being demolished—were renovated and reopened as lounges and beer halls.

As bars proliferated on Rainey Street and on a stretch of nearby East Cesar Chavez, property owners began to list their houses as rentals to take advantage of the proximity to nightlife—smack in the middle of residential areas. Regina Estrada, an Austin native, moved out of her East Second Street bungalow, a block north of East Cesar Chavez, after the house next door became a popular weekend getaway. “Essentially, it was a hotel,” she says.

Estrada’s grandfather Joe Avila founded Joe’s Bakery—which Estrada now runs with her grandmother, mother, and aunt—on East Seventh Street, in 1962. For three generations, her family has lived and worked in the neighborhood, and in the nineties, her father started buying area houses for $20,000 that would now sell for $500,000. When Estrada got married in 2007, her father gave her the house on East Second Street as a wedding present.

“We moved in right at the curve of East Austin really taking off,” Estrada remembers. “Then it just exploded.” At first, the new residents were families and young professionals who sent their kids to local schools and greeted their neighbors. But about five years ago, Estrada began to see a shift. “We were slowly noticing that there weren’t people living in the houses anymore,” Estrada says.

Her daughters, then in elementary school, would overhear crass stories and obscenities from the Airbnb’s pool next door as they jumped on the trampoline in their backyard; a guest waiting for an Uber once opened the door of Estrada’s running car only to find two little girls peering out from the back seat. After several years, Estrada had had enough. “They’re clueless to social norms,” she says. “Not because they don’t have any, but when these people come, they’re here to party, and most people in party mode are not socially conscious. They’re not here to be responsible; they’re here to let their hair down.”

Going Dutch

According to lore, traditional bridal showers originated in sixteenth-century Holland as an alternative to dowries.

Estrada now rents out her Second Street property to long-term tenants and lives farther east—in an area that’s still safe from party houses. But for many people in the neighborhood, leaving wasn’t a lifestyle choice. East Austin, a part of the city historically populated by minorities, has rapidly gentrified over the past decade. That’s part of a larger shift in Austin, the only major growing city where the African American population shrank as the general local population skyrocketed, according to a UT-Austin study that measured growth from 2000 to 2010. In cities across the U.S., gentrification has transformed neighborhoods from “rough” to “full of character” and “safe,” in the parlance of white out-of-towners. Yet the effects are especially dramatic in Austin, the most economically segregated metro area in the country, where a working-class kid is the least likely in the nation to climb into a higher economic bracket, according to Eric Tang, an associate professor of black studies at UT-Austin who authored the study on the diminishing African American population in the city.

“These tourists are trying to access an ‘authentic Austin,’ but what they’re actually doing is dismantling that authenticity because they’re displacing everyday people,” says Tang. “When those who labor in Austin can’t afford to live in Austin, the city becomes an amenity as opposed to a place of opportunity.” When living like a local means pushing out longtime residents—both the hospitality workers and the creative class behind the “authentic” vision of Austin—all that’s left are the tacos, the neon bar signs, and the sanitized bungalows. That’s not a city’s identity. It’s an Instagrammable shell of one.

The bachelorettes certainly didn’t single-handedly cause this phenomenon, but they are a particularly visible manifestation of it. On a recent Friday afternoon, Estrada walks around her old neighborhood. She stops in front of a gray bungalow with white trim, pointing at the front door. “This is one of them,” she says. “You don’t realize until you start reading into it, but the keypads are always the giveaway.” A block later, she stops at another house, equipped with another keypad to let in each weekend’s guests. “This is the party house,” she says. It’s trash pickup day for the neighborhood, and two blue recycling bins sit out front. “You can tell based on what’s overflowing from the trash cans—it’s all alcohol and beer bottles, not like regular trash,” she says. She lifts up the lids of the two bins: Coronas, Corona Lights, pizza boxes.

As Estrada walks past the UT Elementary School, blocks from her former home, a group of women pedal past us on a mobile bar. Kids play on the jungle gym, their laughter drowned out by the voice of Sean Paul, imploring the bachelorettes to “Get Busy”: “Let’s get it on ’til a early morn / Girl it’s all good just turn me on.” “Woo!” one biker shouts at us, raising her beer can in a salute. Estrada shakes her head. “Welcome to East Austin,” she says.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “All the Single Ladies.” Subscribe today.