This article originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Born and Razed.”

In the Duranguito neighborhood, on the south side of downtown El Paso, 89-year-old Antonia Morales likes to walk down the block to her local park. The space is small, about a tenth of an acre, but the grass is green. A few years ago the city installed new sidewalks and red-brick pavers in the area, and Morales thinks the neighborhood—which is less than a mile from the river and Ciudad Juárez—looks better than it ever has. She tries to spend an hour or so at the park when she can, sitting on a bench under an ash tree.

Clean public spaces didn’t exist in Duranguito when Morales first moved here, in 1965. “It was very dirty, very ugly,” she says through a translator. “There were a lot of drugs, a lot of robbery, a lot of prostitution.” The streets were filled with trash: glass and syringes, car batteries and hubcaps. Some of the poorest residents slept on mattresses in the streets.

Morales and her neighbors wanted a better home. They called themselves fronterizos—proud to live on the border—and started cleaning up the neighborhood, block by block. Local activists helped petition the city to put up streetlights and pave the roads. They organized community meetings. “We gathered five hundred people in a schoolhouse to talk to the chief of police, and he agreed to help,” Morales says. “We cleaned the alleys. We picked up the syringes. We cleaned up everything.” Eventually, the neighborhood’s residents had a place where they were proud to live. And then one day, a year ago this month, the city decided it wanted Duranguito to become something else.

The city wanted the land for a “multipurpose performing art and entertainment center.” The larger area surrounding the site of the arena would also be redeveloped. The city council had approved the use of eminent domain to take the land, and many of the neighborhood residents decamped to far-flung parts of the city. But despite offers of compensation, Morales refused. Now she is the only remaining resident of a single-story tenement once occupied by roughly a dozen families. On her street, only one other neighbor remains. They live in limbo while a complicated debate takes place around them.

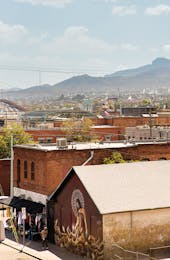

Duranguito and the neighborhoods of Chihuahuita and Segundo Barrio, to the east, form the southern edge of downtown El Paso and shape much of the city’s identity. The proposed arena is just one skirmish in a larger battle that has been going on for more than a decade. Many of the city’s political and business classes are convinced that south El Paso must undergo sweeping changes to fit their version of a modern city. There’s potential for better things, they believe, for this area tucked into a bend along the Rio Grande, between El Paso’s and Ciudad Juárez’s main tourist districts. In a city experiencing tremendous sprawl, these barrios are some of the only viable places to enact the new urban model of density, access to entertainment, and walkability.

But the people living there feel differently. They believe the redevelopment would pluck the heart out of their city. For older residents, like Morales, the prospect of finding equally affordable housing on a fixed income means moving far out to the suburbs, to places with limited transit links and public services, and the loss of a longtime fellowship with neighbors. Many Texas cities have seen gentrification sweep through their urban cores, but in El Paso, the debate has become increasingly bitter and personal, concentrated on a question that’s not so easy to resolve: Who gets to decide the future of a city?

In what could generally be described as a fight between activist groups and developers, Max Grossman exists as an outsider. He’s a militant aesthete with a doctorate in the architecture of Italian city-states as well as a committed conservative. “This is not just about historic preservation,” he says. “It’s about liberty, and restraining government, and transparency.”

Grossman, who teaches art history at the University of Texas at El Paso, served eight years on El Paso County’s historical commission earlier this year. Now Grossman, with the financial support of J. P. Bryan, the owner of the Gage Hotel, in Marathon, is waging a legal battle to preserve the historic buildings on the south side of El Paso. One such building, which brought Bryan into the fight against the redevelopment plan, is a thirties firehouse designed by famed architect Henry Trost, who also built the Gage, in 1927. During the past decade, Grossman has attained an encyclopedic knowledge of this part of El Paso, and on a recent afternoon in August, we set out for a walking tour of the neighborhoods.

In 1859 Duranguito became the first organized residential area of the city. Just about every low-slung brick-and-stucco building has a distinctive story. It has the last remaining frontier-era brothel building, which dates back to 1901 and is known to locals as the Mansion. Grossman is particularly fond of the brothel, he explains as we walk past, because it served as a kind of cultural center for El Paso in the “Old West days,” a place to hear “live violin music.” It endures today as one of the few relics from the city’s, and the state’s, most romanticized period.

When the Mexican Revolution started, in 1910, the people dislocated from south of the river gave these neighborhoods the character of a barrio. In many ways, the area is as historic for Mexico as it is for the United States. Mexican revolutionary Francisco Madero, for example, kept an office here during the revolution, not long before his brief tenure as Mexico’s president.

Pancho Villa’s ghost is everywhere too. Villa spent his exile in Duranguito before returning to Mexico to take over the famed División del Norte. He hoarded guns and gold in houses around the neighborhood. One building in the arena demolition zone, which Grossman says is one of the “first Victorians in town,” was the office of the lawyer who negotiated Villa’s final surrender to the Mexican government.

A few blocks away, there was the Emporium Bar, a hangout for spies and journalists during the revolution. Villa was a fan of the bar’s strawberry sodas. He stayed in the hotel next door with his crate of homing pigeons. One day, Colonel Maximilian Kloss walked into the bar and, according to some histories, offered the kaiser’s arms in exchange for German access to Mexican ports. This was part of a string of events that led to the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret cable from the German Foreign Office proposing an alliance with Mexico, and, ultimately, leading to America’s entry into World War I. The rest is history, and now the Emporium Bar is too: in 2003 the building was flattened to make way for a Burger King. Few people noticed at the time.

Grossman cares particularly about the architecture and the history, but the neighborhood’s residents have, perhaps, more important things in mind. These barrios have long served as a way station for immigrants heading deeper into the United States, the reason some call it a “second Ellis Island.” Still-operating tenements, clean and well maintained, offer a safe and cheap place to stay. The community has always oriented itself toward helping migrants, said Father Eddie Gros, who presided over Sacred Heart Parish in Segundo Barrio during the past decade. “A lot of the people in the parish were not documented,” Gros says. “Any plan that eliminates housing and offers federal housing as a replacement makes it impossible for people who pay their rent in cash to find a place to live.”

The real trouble between the developers and south El Paso dates back to the turn of the millennium. At the time, most of Texas was undergoing a population explosion and economic boom. El Paso was not. The North American Free Trade Agreement had brought money to the city, but it also decimated the city’s garment industry, which decamped for the other side of the river. And in 1999, one of the city’s largest employers, the toxic Asarco smelting plant, shut down.

The question was, what’s next for the city? In 2004, a body that included El Paso’s and Juárez’s most prominent businesspeople, including many of the area’s top property developers, formed the Paso Del Norte Group and commissioned a study to answer that question. A year later, a Supreme Court decision opened the door for local governments to use eminent domain to seize land for private economic development. In 2006, the Paso Del Norte Group released its plan for a large-scale redevelopment of downtown’s south side, which would affect some three hundred acres.

At the same time, El Paso’s old-guard city council members were losing seats to a crew of young reformers who considered themselves urbanists. They were El Paso natives who’d lived elsewhere and returned, and they wanted other young people to return as well, to attract and retain new business talent, and to jump-start the city’s economy and increase its low median wage. The Paso Del Norte Group’s plan for a renewed urban core provided the road map. In the summer of 2006, a marketing firm was hired to develop an ad campaign highlighting a vision for the future of El Paso. The instantly infamous presentation to the council that followed offended nearly everyone who saw or read it. “El Pasoans are extremely negative about their own city,” the report read. Images associated with the “old” El Paso included a picture of an older Hispanic man in a cowboy hat, accompanied by the words “Dirty,” “Lazy,” “Speak Spanish,” and “Uneducated,” while the vision of the new El Paso featured pictures of Matthew McConaughey and Penélope Cruz, accompanied by the words “Educated,” “Bi-lingual,” and “Enjoys entertainment.”

Residents of the south side took particular offense, and a new activist group, calling itself Paso del Sur, started to organize the community. Which is hard to do, says David Romo, a historian and activist with Paso del Sur, because so many of the neighborhood’s residents are older or undocumented. “Immigrants who congregate in places like Segundo Barrio and Duranguito don’t want to rock the boat,” Romo says. “So it’s easy for city hall to ignore them.”

Opposition from the neighborhood groups stalled the development before the global financial crash stopped it, but the foundation was set. In 2012, the city council decided to take another crack at it, centering on another redevelopment proposal. The city held a “Quality of Life” bond election in November of that year with the goal of funding a Hispanic cultural center, a children’s museum, and the arena.

The measure passed, and developers began buying up land in what they thought would become the arena footprint. But the city had jumped the gun. In 2016, opponents of the plan launched a legal challenge. In the city’s haste to pass the bond, a decision had been made to omit the mention of “sports” in the ballot language. Opponents charged that the facility must be legally limited to the language voters approved, which is to say, the performing arts and entertainment. In August, a judge in Austin sided with the opponents, ruling that the city could not legally use the money raised to build a venue designed for sports. Without that, the arena wasn’t financially feasible.

Dionne Mack, El Paso’s deputy city manager, says the goal is only to build “a vibrant and liveable downtown.” El Paso has trouble attracting investment and young business talent, she says, because of its isolation, the perception that big-city life is, at best, a six-hour drive away. “I want our kids to say, ‘I want to stay here. I want to live here,’ ” she says. “Who is going to build and invest in this area if the plan doesn’t go through?”

But the project is opposed by a few elected officials. One of the strongest opponents is El Paso’s state senator José Rodriguez, who wants to see the city instead develop its heritage tourism and historic preservation portfolio (his wife, attorney Carmen Rodriguez, joined a legal team representing residents in court). “I don’t want to say that they’ve been bought by the developers,” he says of the city council, “but they’ve at least been brought into their corner.”

On August 22, the city council met in executive session and voted six to one to retain its legal team, move forward with the appeal of the court’s decision in Austin, and try to win the right to build the sports arena it wants. Meanwhile, the city plans to begin demolishing eight buildings it owns in the arena’s footprint, pending an archaeological review required by the state. Neighborhood activists are collecting signatures to put a measure on next year’s ballot that grants Duranguito a historical designation. They suspect that if the city can’t include sports in the arena’s purview, it’ll junk the project. In the meantime, residents of the surrounding area, including Morales, are attending regular meetings to generate an alternate development plan to submit to the city if the arena fails for good.

The council’s sole dissenting member was Alexsandra Annello, who represents a district on El Paso’s northeast side. The thing pushing the project through at this point, Annello says, is momentum, and the perception of sunk cost. There’s a steep learning curve for new members of the council figuring out the nuances of the fight, she points out, and the city has spent a lot of money on this plan and a lot of money buying up property.

To Annello, the problem for the south side isn’t economic as much as a failure of imagination. El Pasoans, she says, have historically looked to the rest of Texas to figure out what they’re supposed to be. “We’re not Fort Worth, and we’re not San Antonio,” she says. “I grew up in the north end of Boston, a really historical neighborhood that has been gentrified. But at the same time, there are these areas, like Little Italy, with people who have owned homes forever. Boston worked really hard with the residents to keep that area the way it is. I just wish that was a consideration here.”

The conflict over the arena bid, Annello says, is as much about culture as it is about development. Take the name of the neighborhood itself. Though Grossman says “Duranguito” is found in historical records—the name is a nod to those who came from the Mexico state of Durango—it entered popular usage, according to Annello, only after “the idea of the arena came up,” as the neighborhood was developing its opposition to the city. The city, meanwhile, would prefer the neighborhood to be known as “Union Plaza,” which Annello says is equally new: “I had never heard that area referred to as Union Plaza.” As long as that cultural tension is unresolved, the development fights will continue as well.

Senator Rodriguez, lamenting one of the city’s newer branding attempts—a Hanna-Barbera-style mascot known as Amigo Man—puts it more bluntly. “To capture what El Paso really is, you need to accept the Mexicanness, the Mexican American, and indigenous roots of El Paso,” he says. “There’s too many people who say, ‘I want us to move away from that. I want us to be like Gringolandia, like all the other homogenized American cities.’ El Paso is unique. You can’t find a place like this anywhere.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy