Ben Lamm doesn’t sell spoons. Declaring as much is a favorite line of his whenever someone asks what his two-year-old company, Hypergiant, does. What he means is that he doesn’t produce anything as uniform and universal as utensils. Were he a purveyor of tableware, he wouldn’t have to spend so much of his time customizing products to individual clients or explaining what can be done with them. Everybody knows what spoons are for.

Contrast that with the broadest definition of what Hypergiant does in fact sell—artificial intelligence-enabled software and hardware—and you’ll appreciate Lamm’s problem. Even many people lacking in technological savvy have heard of AI as a force with the potential to shape much of humanity’s future—for better or worse. Some of those people look to get into business with Hypergiant without any real idea of what it is they’re buying. They just know they want some. “It’s like the most addictive drug that no one’s ever had,” says Lamm, who serves as the company’s CEO.

Formed in late 2017, Hypergiant is the latest and by far the most ambitious enterprise launched by serial entrepreneur and Austin native Lamm, who previously founded and sold several companies in the realms of e-learning software, art and design technology, and AI-enhanced chatbots. Hypergiant has offices in Dallas, Houston, and Austin, and it has grown from just a couple dozen employees at the time of its official launch to a current staff of more than two hundred. Planning for the opening of a Washington, D.C., office to focus on defense-related opportunities is under way.

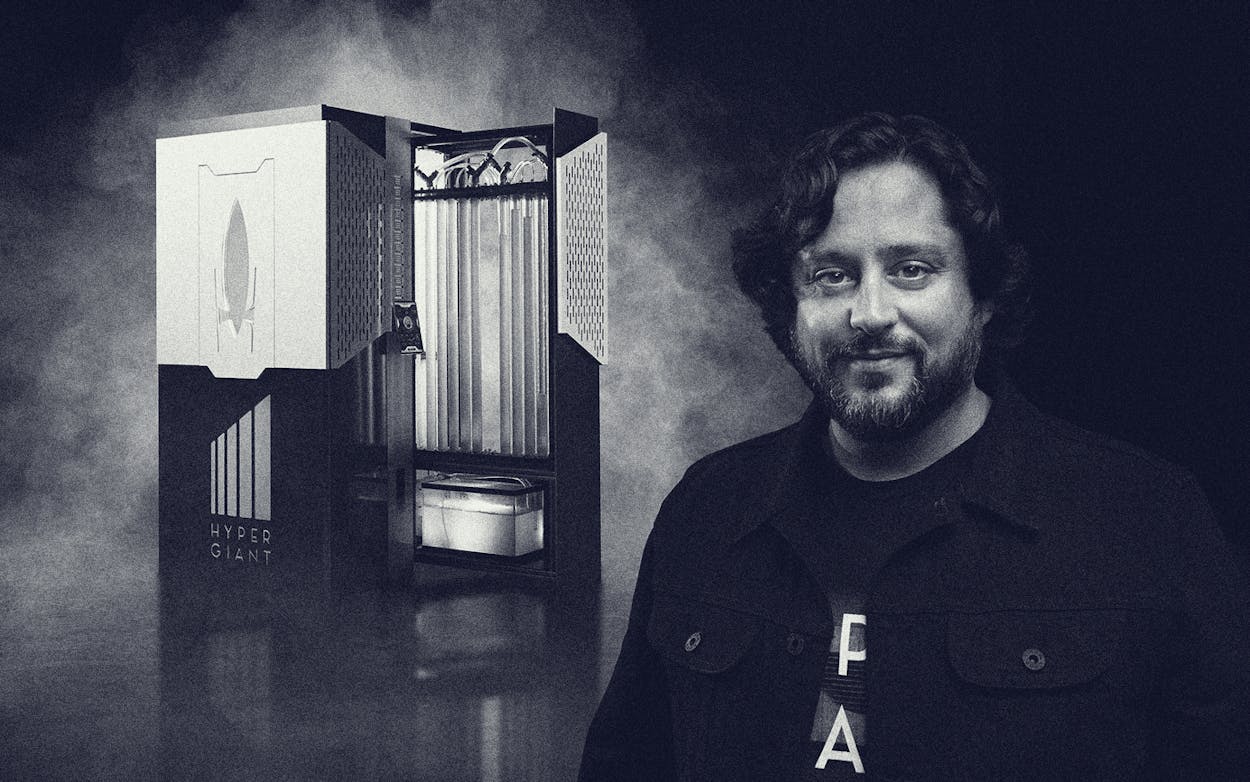

At the company’s downtown Austin office, all the conference rooms are named for evil AI from pop culture. I met Lamm in Dolores (as in the villainous android on HBO’s Westworld). Bearded and wearing his dark, wavy hair long atop a short, stocky frame, the 38-year-old Lamm is given to long answers in which his abundantly active mind has a way of veering from one subject to another without much warning.

The company had just eagerly publicized its Eos Bioreactor—essentially a small box in which AI software manages the growth of algae, which naturally removes carbon dioxide from the air. While it’s just a prototype, Hypergiant has plans to build a commercially sized successor that could hook up to HVAC systems to reduce the carbon footprints of buildings. We discussed that and other ways in which Lamm believes AI will transform our world. He’s not shy about touting his and his company’s accomplishments, nor about his goal for one day building Hypergiant into a trillion-dollar enterprise.

Texas Monthly: Hypergiant aims to help its clients gather and analyze vast amounts of data. You’re working on improving the sensory perception of machines. You’re aiming to launch a network of small satellites gathering data from above. And you’re looking to empower “smart cities,” stitching together data from cameras that are increasingly everywhere. So why use resources on building a better bioreactor? Fighting climate change seems like it’s outside your core, data-focused business.

Ben Lamm: You don’t have to be in the algae business or in the ocean business or in the fossil fuel industry to worry about these things. I believe that if you have really smart women and men that work for you, and you’re a company that has the ability to invest and create the future, then I think that we have a choice of where we want to spend that time and those resources. For us, and I hope for the world, climate change should be one of those things. Do I think that we are going to solve climate change? No. Do I think that we can be a part in it? I mean, look, we will open-source the plans. And then if everyone just goes and builds their own bioreactor—great, awesome. We make money in a lot of areas. I don’t need to make a trillion dollars off of the bioreactor. Now, it will be a part of our smart cities initiative, because I think you need to be building carbon-negative cities.

TM: Do you think technology’s going to save us from climate change?

BL: I believe that people will. If you just get the cities on board, you don’t even need to get the states on board. If you go get the big cities—you go get Miami, Austin, Dallas, Houston, D.C., New York, San Francisco, L.A., Chicago? If you get the cities, we can make a huge impact. We don’t need the federal government to mandate climate change or carbon offset tax dollars or whatnot.

TM: Are you what I think of as an AI utopian—in the sense of people who see nothing but good that AI is going to do?

BL: Look, I’m a realist. The big thing that I believe will cause the most disruption is automation, not AI. This is going to sound terrible, but we’ve been through this before. Will there be troughs? Yeah. I mean, my last business, we were a conversational intelligence platform, and people were like, “You’re going to get rid of all these people’s jobs at call centers.” We were like, “But those jobs should never have existed.” A call center agent is basically a biological natural language processor. They listen to the words that another human says, on a phone, they type those words into a script, and then it tells them what to say. That’s a mindless job. I believe that person could be an artist. Or that person could be a space engineer. Or anything. I do think that it’s going to cause disruption. I don’t think we’re going to turn into Terminator. I don’t think that it’s going to take all the jobs. I think we’re going to have a duty to humans to re-skill them and retrain them. One of the things I don’t love by the way, in AI—you’ve seen this whole trend where it’s like, AI-powered art and AI music?

TM: They’re going to write novels.

BL: I hate that. I f—ing hate that.

TM: Why is that?

BL: Because I think that we should use these technologies to give humans the data, so that they can make better decisions, informed decisions, and it should automate the shit that we shouldn’t be doing. But I think arts is where I draw the line. Why don’t we spend that time making AI robots that are solar-powered that go around and clean up the ocean? There’s a lot of other stuff that we could be doing instead of training an AI to paint as well as Monet. People talk a lot about ethical AI: will AI have bias if it’s trained by all white men?

TM: And it clearly seems like that’s been happening.

BL: Yeah, but it’s also not technology’s fault. It’s humans’ fault. Did you see when San Francisco banned facial recognition tech? I think that’s dumb.

TM: Why is that?

BL: Because they were like, “Here’s what China’s doing with facial recognition tech,” which is really bad and evil. China is segmenting humans based on physical facial characteristics, based on an assumption of their religion. Evil, terrible shit. China shouldn’t f—ing do that. No one should do that, but that’s bad decisions leveraging that technology. But here’s what China is also doing: they’re advancing facial rec tech. Some of the smartest tech minds in San Francisco and the Valley, were like, “Oh, well, if other cities are going to ban it because other people are doing bad stuff with it, then we’re not going to invest in it,” and therefore the technology’s not getting advanced. So China’s getting more advanced in that category, because we’re taking the stance of “bad people use technology to do bad things.”

TM: But aren’t you at all sympathetic to the privacy argument? Cameras everywhere, all the time, watching everything that I do?

BL: Look, I probably don’t have the right perspective on privacy, right? There’s certain things I don’t obviously want anyone to know or people to know. But I think there’s a trade-off, right? We want a world where everything just shows up to our house, now even same-day. We want a world where we don’t have to do fifty million things to get on an airplane. We also want a world where all of that is safe. Where what comes to our house doesn’t blow up, or we don’t get in the sky and blow up, right? We want that world, there’s trade-offs. I think there’s a privacy-to-convenience trade-off. I think that’s an individual thing.

TM: The problem is, if that decision effectively gets ceded to the government or large corporations, then I end up not having a choice about it, right?

BL: Yeah, but I mean, drive down the street. Look how many cameras there are. I didn’t put those cameras up. Do you have Apple?

TM: I do.

BL: So I get an Amber Alert all the time. There was some news thing I saw that, Amber Alerts’ hearts and minds are in the right place, but it’s been very ineffective, to find missing children. If you could find a child that was abducted in minutes, before some god-awful something happens to them, what’s the trade-off? There’s trade-offs to privacy, security, and convenience.

TM: Considering the current occupant of the White House, and the recent abuses of power that have come out, think about a government having access to that information, and someone who isn’t necessarily ethical or moral has that.

BL: Those people are going to exist. Those regimes, like China. They just kind of do whatever Xi wants there. Those regimes are going to exist, and the technologies are going to exist. Taking a blind eye to the technology is not something I think is a good idea, though.

TM: But you seem less concerned about it than some people. You trust in the goodness of humanity? Is that where this is coming from?

BL: I do. I don’t think it’s naive. I do believe in the goodness of humanity. I do believe in the goodness of tech. I think it all kind of wins in the end.

TM: Does the Texas of the future mean big cities where there’s a camera on every corner and cameras throughout every building?

BL: I think that’s already existent. I told my wife this a couple of weeks ago. I was on a toll road in Dallas, driving down the toll road. There’s like—I don’t know how many feet, but like every twenty yards—there’s camera pods. It looks like a little robot alien. So I kind of think that’s already out there, right?

TM: I’ve noticed you put a lot of energy and time into your branding—your marketing and your branding and this sort of retro-futuristic aesthetic that you apply to everything. I also saw a magazine article where you said you spent six months on the branding of Hypergiant before launching the company. Why is that so important?

BL: I do care a lot about branding. Nothing goes on our website I don’t personally look at or give feedback. Nothing. Nothing goes on social media that I don’t see. I think the cultural zeitgeist of an organization should manifest itself in the written word and in the visual implementation of the written word, of who you say you are. Good brands resonate with people. We are not going into meetings where people are like, “What’s Hypergiant?” People have heard of us. I think part of that is because I think we spent a lot of time and attention to detail.

TM: So why are you doing this in Texas? The sorts of tech you’re working in more often comes out of places like Silicon Valley or Boston. Why are you here?

BL: I am a big believer in Texas. I have a house in Austin, a house in Dallas. I was born in Austin. You can build a multibillion dollar company without leaving Texas. There’s just so much opportunity, with the energy center being in Houston, and you’ve got medical and real estate and finance and other industries as well in Dallas. I’m super pro-Texas. I will never live anywhere else.