This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

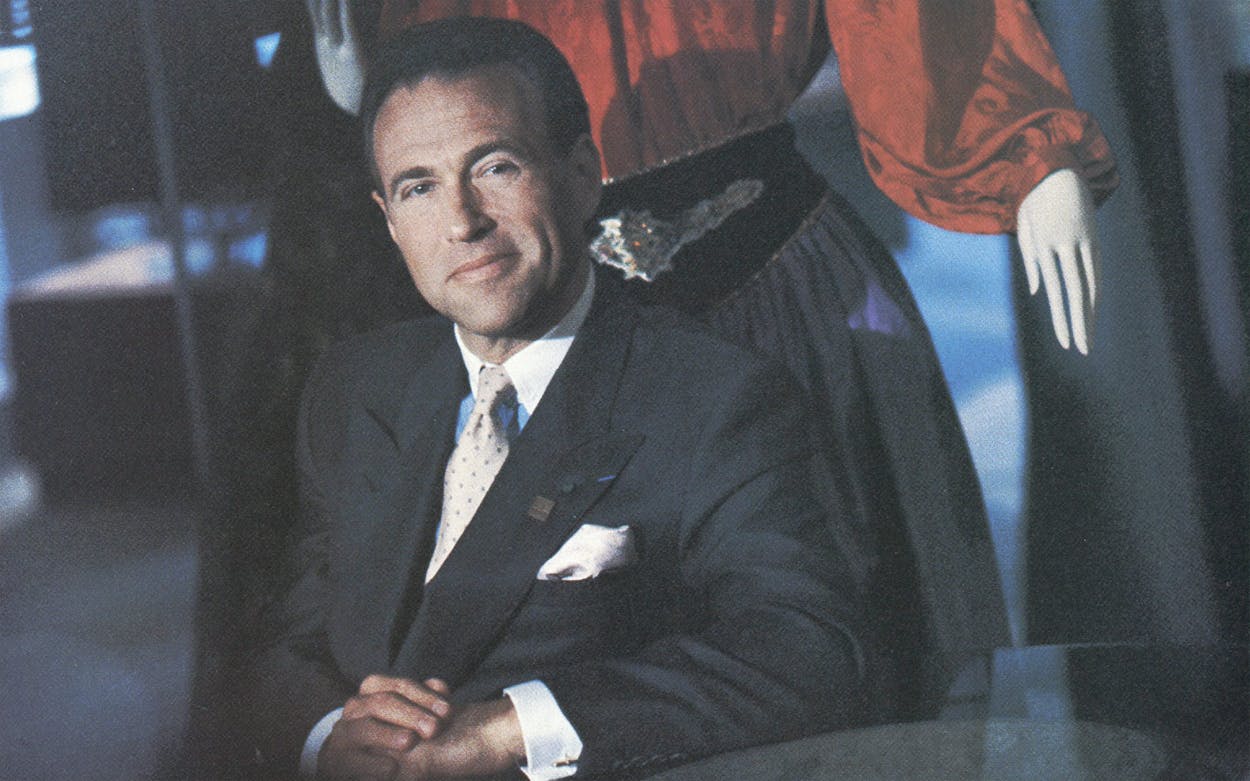

Do me a favor and don’t spoil my Christmas business,” says Robert Tobias Sakowitz, glaring from behind a desk so buried in reports, printouts, files, and old paperwork that it would quicken the pulse of an archeologist. Outside, the late September sun slants down on the chaste white-marble sweep of the downtown Houston Sakowitz store, its sidewalks empty as a De Chirico painting on this Saturday afternoon, a corner show window cracked and papered over. The president and chief executive officer of the 83-year-old specialty store chain paces his richly appointed third-floor lair, wearing brown alligator cowboy boots, testy and combative. The fabled Bobby Sakowitz charm is not in evidence; the long, vertical dimples and cheeky smile that have graced so many lifestyle sections for so long are conspicuously missing. Because Robert Sakowitz is sick of it: sick of the critical press he has received since his family-owned Sakowitz, Incorporated, filed for protection from creditors under Chapter 11 of the federal bankruptcy law; up to here with the sudden-growth industry that second-guessing his management style has become. He’s steamed about that Business Week piece, “How Bobby Sakowitz Took an Escalator to the Basement.” He’s got his own blame to cast on the “negative” press and “intransigent” banks, on the gossipy market and skittish suppliers, on bad ex-employees and the ferocious competition in Houston’s crowded, depressed retail scene, and on the unforeseen horrors of the oil bust. In a few scattered comments in a few scattered interviews—and, one suspects, in the middle of the night—he has even blamed himself.

Not without cause. A company the size of Sakowitz, which grew from Houston’s indigenous carriage-trade store to a three-state chain of seventeen units with sales of more than $120 million, generally fails for complex reasons. But if one thing stands out in the tangled legalities, economic forces, internal problems, and recriminations that mark Sakowitz’s slide into Chapter 11, it is this: Robert Sakowitz bet like an oilman and lost like an oilman. His rapid expansion into the energy-related markets of the Southwest was predicated on exactly the same notions that fueled oil-patch hysteria in the early eighties: that the price of oil would keep rising, that the aggressive entrepreneur could leverage himself to the hilt based on projected earnings that could only climb. Restraint? Forget it. It was time to expand while the expanding was good. The whole phenomenon was tailor-made for a self-styled maverick who romanticized his role as retailing’s “weirdo” wildcatter, unhindered by the strictures of public ownership. Robert even dressed the part, packaging himself in cowboy hat and boots for the biannual Paris fashion shows. But by the time the bottom dropped out of oil prices in 1982, Sakowitz had borrowed heavily to move into markets like Tulsa and Midland that were starting to reel from the bust. The stage was set for the frantic juggling act Robert, like many oilmen, would have to perform to service the store’s debt.

Because he was running a family-owned business, Robert’s personal inclinations had free rein. His voluminous ego (one thing his admirers and his detractors seem to agree on); his far-from-potent board of directors made up of close relations and company insiders; the absence of a strong presence like his father, Bernard, who died in 1981; a reluctance within the company to buck the boss—all practically guaranteed a one-man show short on checks and balances. A former associate who worked closely with Robert for years says, only half in jest, “I think the first people ever to say no to him were Chase Manhattan”—leader of the banking group that pulled the plug on Sakowitz in July.

But the latest chapter in the Sakowitz saga is far from the story of one man. Family imperatives, as well as personal ones, are at work here: the powerful romance with real estate, passed down from company cofounder Tobias Sakowitz to his son Bernard to his son, Robert; the ideal of progress in a family of immigrant Russian Jews who began life in America selling work shirts and jeans to sailors on Galveston’s wharves. Each of the next two generations topped the one before it—in square footage, toniness of merchandise, and scope of reputation—a mandate that has never been lost on Robert.

As the only son in a traditional Jewish retailing family, Robert looked to the stores to make his mark. His expressed determination was to win an international name for the chain and to professionalize its management techniques. Robert always bridled at the inevitable comparisons with Neiman-Marcus, to which Sakowitz had played second fiddle for decades. But there is little question that he attempted to capture the public’s imagination in the definitive way that Neiman’s always had. And there is no question but that he tried to compete with the conglomerate big boys —Neiman’s under the Carter Hawley Hale aegis, Bloomingdale’s, and all the rest—who wrote large orders for merchandise with what the trade calls the Big Pencil. Preferential treatment from suppliers was implicit in the Big Pencil; so was prestige and the occasional shot at an exclusive. One way to acquire that clout was to increase volume with the kind of aggressive expansion program Robert undertook in the late seventies.

The imperatives of place and time played a part in Sakowitz’s decline too. The Sakowitz story echoes the Houston story, beginning with the city’s days as a fledgling port hell-bent on eclipsing Galveston. It’s all there: Houston’s transition from a bumptious Southern town with big ideas to a sprawling international city with big ideas; the growth of the suburbs and the decline of downtown; the influx of newcomers from around the country. Finally, the Sakowitz story speaks of some hard-won latter-day truths: the realization that rampant positivism is a double-edged sword, that growth is not necessarily Houston’s by divine right. The tale even hints at the latest wrinkle in civic folklore, the brand-new Houston cult of Chapter 11, a macho creed whereby executives tout their passage through bankruptcy court not as a setback but as a glorious opportunity for change.

Small wonder that Robert Sakowitz is on the defensive as he sits in the perpetually twilit chiaroscuro of his downtown office, fielding the unwelcome questions about what went wrong. Among the proliferating stacks of books and projects the old familiars surround him: the scores of bibelot owls, the genteelly worn Oriental carpets, the seventeenth-century Dutch portrait of a woman, wreathed in a lace collar, so crisply rendered and light-filled you want to reach out and touch it. Amid photos of the powerful and famous are sultry black and white studies of Robert’s new wife, Laura, to whom he coos periodically on the phone when she calls to keep him posted on a fever she is running. Drapped across a round table are elements of a carefully chosen costume: the beige Western-cut jacket to go with the perfectly fitted brown checked shirt he is wearing; the cowboy hat banded in feathers from pheasants shot at the ducal estate of a titled Harvard chum.

In a few weeks every paleolithic layer of this office will be excavated and removed across town to the Post Oak store; the downtown store will be shuttered for good. The once profitable Gulfgate store on Houston’s East Side will close, along with most of Robert’s out-of-town stores and boutiques. The ebullient tone that marked his professionally orchestrated interviews immediately following the bankruptcy announcement has given way to the grim reality of struggling through “the Chapter,” as Robert calls it with biblical gravity.

And then there’s Christmas, arguably the most vital Christmas of Robert Sakowitz’s life, the one he doesn’t want reporters to ruin. This single holiday season can be a troubled retailer’s lifeblood; it can set the cash flowing, which keeps the merchandise rolling in. Last year, when it looked as if Sakowitz might be lost, Christmas sales were strong enough to stave off the crisis. Now, with his stores hurting for new merchandise, with suppliers reluctant to ship their wares for fear they won’t be paid, with many demanding cash on the barrelhead —the question is whether Robert Sakowitz can pull off another redemptive Christmas.

More Pretentious Quarters

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Robert was the gilded heir who would breathe new life into an old-fashioned business, not the man who would usher it into bankruptcy court. The history of the Sakowitz family is one of those textbook success stories of hard work and ample reward, leavened with the civic involvement that has animated many prominent Jewish merchant families in America. The Sakowitz annals are imbued with the simple conviction that if one labors long and treats the public right, all will be well. For eighty years the family had no reason to think otherwise.

In the mid-1880s Louis Sakowitz, a big man with a big beard, arrived in Galveston with his wife, Leah, and several young children. They had left Kiev as part of a massive exodus of Russian Jewry, among the first of thousands of East European Jews who were then being funneled through the Gulf Coast, away from the crowded Eastern ghettos. Soon Louis opened a dockside store that sold work clothes to seamen. It was a cultural given that his eldest son Sam would join the business. Since the store wasn’t big enough to support the two younger boys, they quit school in 1900 and found work as ten-cents-a-day clerks. Seventeen-year-old Tobias managed a notions shop; fifteen-year-old Simon sold sailors’ gear down on the wharves. The teenagers saved their money and kept their eyes open. Two years later, Tobias and Simon had saved enough to open Sakowitz Brothers, a modest little Market Street shop. It differed from their father’s store in one important respect: the brothers had divined that the road to success would be paved not with humble work shirts but with quality men’s furnishings. They would not sell mere suits, they would sell Hickey Freeman; they would not sell cowboy hats, they would sell Stetsons.

In 1910 the young brothers made the shrewdest business decision of their lives by borrowing money to buy out a store in what was then the center of downtown Houston. In the years after the catastrophic 1900 hurricane, it had dawned on some Galveston investors that Houston might well turn out to be the coming city, and the Sakowitz brothers were determined to go where the public was going to be. By 1912 the Houston location had doubled in size and outstripped the ten-year-old parent store. After the storm of 1915 smote Galveston and the Houston Ship Channel opened shortly thereafter, the brothers closed the Galveston shop, and in 1917 they moved into three floors of the Kiam Building at Main and Preston.

A quantum leap up the retailing ladder, the Kiam store tripled the brothers’ space. An announcement in the newspaper, graced with a fetching classically draped maiden in a headdress emblazoned “PROGRESS,” saluted “the public, through whose confidence and loyalty we are able to enjoy the facilities of more pretentious quarters.” And indeed the new store “for men & boys” was flossy, with a boys’ miniature barbershop and “everything under glass.”

By 1929 civic honcho Jesse Jones had wooed the growing business into five floors of his thirty-seven-story Gulf Building, quadrupling the store’s space. The new quarters made a big splash. Forty thousand people showed up for the grand opening—this, in a city of 300,000. Press accounts paid the building the ultimate compliment of the day when they said it looked like a bank. When the stock market crashed, the family pulled through because it did not owe a dime on its new location.

The Gulf Building move marked the start of Sakowitz’s women’s apparel division (which was leased to in-store franchise operators until 1951) and the ascendancy in the company of Tobias’ son Bernard. Unlike Neiman-Marcus, which had opened in Dallas in 1907 with the express intention of becoming the Texas rich woman’s store of choice, Sakowitz had made its reputation in menswear. Now came Bernard, fresh out of the Wharton business school and an executive training program at Macy’s in New York. He didn’t know a great deal about womens wear, but then, his father and his uncle knew nothing about it. Bernard oversaw the women’s franchise operation and—just as his son would—became entranced with what he called the “creativity” of marketing the rapidly changing fashions.

Something akin to a Sakowitz folklore, fraught with ideas about family and community, was beginning to take shape. Every evening, “Mr. Simon” and “Mr. Tobe,” as they were called in old-school retail family style, would line up at the back entrance along with “Mr. Bernard” and “Mr. Gaylord” Johnson (Simon’s son-in-law) to bid good night to the departing employees. Mr. Simon and Mr. Tobe may not have paid princely wages, but in patriarchal fashion they were there with personal loans for employees in need and began a company tradition of no mandatory retirement that persists to this day. The company’s solicitude for the customer was by now approaching a religion—a religion all good employees were expected to share. Margaret Askins, Bernard’s right-hand assistant for many years, recalls staying late one Christmas Eve to wrap packages with Harry Kuper (now a fifty-year man and vice president) and then personally delivering the gifts to customers’ homes. Today it’s hard to find a veteran Houstonian who doesn’t have a tale of Sakowitz accommodation beyond the call of duty. One woman remembers the Sunday after her father died, when Mr. Tobe opened up the downtown store so her family could pick out a burial suit.

But above all, it was through their liberal credit policy that the Sakowitzes turned their store into a Houston institution. Their forbearance became legend and persisted well into the era of sophisticated credit controls. Architect Burdette Keeland, Jr., outfitted his four children at Sakowitz in 1959, just before going to Yale to take his master’s degree. Six months later came a nice, personal letter from the store saying, “We notice you’ve left the state.” Keeland wrote back explaining his financial embarrassment and soon received a reply signed by Bernard. It said, “When you get out of Yale, just send the money.”

Their store was a local institution of some consequence, and the two brothers spent considerable time in good works, but none of that was enough to exempt the Sakowitzes from what one Jewish professional dubbed “the five o’clock curtain,” that barrier that separated Jew and Gentile after work hours. Neither the rarefied Houston Country Club nor the River Oaks Country Club welcomed Jews, so Tobias and Simon became charter members of the Jewish country club, Westwood, and helped keep it afloat during the Depression. Nor did River Oaks’ deed restrictions allow those of the Jewish faith to live there; like most of the Jewish gentry, the Sakowitzes gravitated instead to the affluent Riverside neighborhood.

Bernard’s younger brother Alexander actually took the step of changing his name to Sackton, although he says it was not in response to the kind of anti-Semitism that infected Texas during the thirties. After graduating from the Wharton business school according to plan, Alexander surprised everyone by going on to study literature at Cambridge and Harvard. When he took a position at the University of Texas in the forties, he Anglicized his name—in part, he says, because he was tired of people constantly asking “why I wasn’t minding the store,” and in part because it seemed “natural” for a professor of English literature to have an Anglicized name.

Whatever difficulties a Jewish name might have imposed, this much was certain: people with names like Sakowitz could become retailing royalty. That is no small part of the reason why so many of America’s prominent retailing families have been Jewish (in Texas alone, the Sangers, the Harrises, the Marcuses, and the Frosts all flourished, to name a few). They were good at it not only because of their energy and ambition and skill but also because they had to be good at it.

In Houston during the late forties, the Sakowitz family once more found its arena expanding. At almost 600,000, the city was twice the size it had been when they opened their Gulf Building operation. Tired of rearranging and eking out space wherever they could, the Sakowitzes called in Alfred C. Finn, court architect to Jesse Jones. What Finn wrought for them downtown was a monumental expression of second- and third-generation Sakowitz taste. The new Sakowitz building was five stories of white Vermont marble—“the South’s Largest All Marble Building”—cast in “classic Greek” form (Tobias had acquired a penchant for the classical style on a 1936 tour of the Mediterranean coast). The recessed entrance towered, flanked by metal clusters of Southern magnolia blossoms; the facade glistened in a sheer, almost windowless expanse. The 1951 grand opening occasioned torrents of overheated prose in the papers and an entire Eastern Airlines flight—“the Sakowitz Special”—which took off from New York laden with favored vendors and fashion dignitaries. No one ever seemed to tire of pointing out that the new store more than tripled the size of the old one, or that it was one hundred times bigger than the original Sakowitz Brothers.

The new store opened right before the Eisenhower recession. But Sakowitz weathered the trouble well and proceeded upward along the growth curve in tandem with Houston. The family began to look beyond downtown, opening a small boutique in wildcatter Glenn McCarthy’s splashy new Shamrock hotel, way out in the boonies of South Main Street. It was a moment of vision; the Sakowitzes signed on early to the suburban trend that would come to dominate American retailing, taking their wares to their customers’ neighborhoods. In 1956 they opened a store in the Gulfgate mall, the first regional shopping mall in the Southwest, on the east end of Houston.

Just as the Sakowitzes began looking past the horizon of one store, they went head to head with their biggest competitive challenge yet: Neiman-Marcus came to town. In 1955 the Dallas powerhouse opened just blocks from the downtown Sakowitz. No longer would Sakowitz’s local hegemony over quality and service be enough, because Neiman’s turf included high style as well. Stanley Marcus was already a legend in the fashion world. He had advertised nationally for decades, he had won the attention of the fashion press, and—most vital of all—he had made his store the darling of all the upscale women’s apparel vendors in the country.

Neiman’s had clout, and therefore Neiman’s had an exclusive lock on many American couturier lines that Sakowitz coveted. But Sakowitz could compete on other grounds. There was the hometown advantage. Sakowitz had created a niche for itself as purveyor of blue-chip family gear—carefully embroidered Camp Waldemar tribal shirts for girls; proper khakis and whites for St. John’s, the prestigious River Oaks private school where Robert Sakowitz was then a student. It had become expert at the care and coddling of brides. Bernard had even tried his hand at some splashy, Neimanesque promotions, like banking the first floor with thousands of yellow Tyler roses, a Houston first.

But it was with the Sky Terrace that Sakowitz had the edge on Neiman’s. Styled as a Southern colonial courtyard, the top-floor restaurant was fabled for its black waiters and its shrimp salad. In its heyday the Sky Terrace was a rendezvous, a cherished landmark. Modeling executive Gerri Halpin, a former fashion director at the downtown store, says she still runs into people from Bryan, Victoria, and Beaumont who reminisce about Christmas shopping trips that had to terminate downtown so they could eat at the Sky Terrace.

If the fifties marked the beginning of hefty competition, it was also the decade for a bold new move. Bernard, who took the company helm in 1956, mounted a westward expansion that was the crowning achievement of his career. He built a large store at the intersection of Westheimer and Post Oak that not only cemented the family’s commitment to the suburbs but also was a prescient move: although the Galleria now thrives on that corner, at the apex of Houston’s densest commercial corridor, in the late fifties the land was mostly undeveloped pasturage. But Bernard took stock of the cushy neighborhoods nearby—River Oaks, Tanglewood, inner Memorial. In lieu of fancy demographic studies, he and Tobias, always so mesmerized by real estate prospects, did something that will live forever in Sakowitz mythology: father and son sat themselves down on that scrubby corner and counted the cars that went by. They sat there all day, and they counted a lot of cars. So in 1959, again with great civic drumrolls and with the mayor on hand to cut the ribbon, the Post Oak store opened. A Confederate flag flew at the entrance, as if to emphasize that Sakowitz—with its old-school patriarchs, its platoons of faithful retainers, and its starchy, determinedly patrician air—was very much a Southern store. Bernard himself decreed its plantation-house look; a devotee of the colonial style, he felt a white-columned country-clubby store would appeal to its suburban clientele.

The fifties marked another event that was to shape the company—in 1956 Robert Sakowitz went to Harvard.

A Big Fish in a Big Pond

Cambridge was a different world, one that was to profoundly influence Robert and ultimately the family business. By his sophomore year he had joined forces with an extraordinary group of history-major roommates: Michael Rockefeller, Nelson’s son, who in 1961 was lost in New Guinea on an anthropological expedition; Wat Tyler, a descendant of President John Tyler; and Sam Putnam, one of whose forbears had been a Revolutionary patriot. It was a crew of American aristocrats guaranteed to heighten any eighteen-year-old’s sense of lineage, let alone destiny. Rockefeller in particular “helped pique my curiosity and interest in the arts,” says Robert—an interest that came to figure in his ambitions for the stores. “Boston, Cambridge, Harvard gave one an overwhelming sense of respect for the intellect, as opposed to the externals,” he recalls. Quick, bright, articulate, relentlessly theoretical, Robert fit right in as an intellectual, a role he would play with great passion in his retailing career.

One bit of Sakowitz lore had Bernard telling little Robert that he could be a big fish in a small pond or vice versa; why, demanded the child, can’t I be a big fish in a big pond? Almost everything in those Harvard years must have conspired to turn Robert’s vision toward an arena more significant than the one he had left behind. If his father had been the consummate Houstonian, the dedicated chamber of commerce man, then Robert was shaping up to be something else—the dedicated man of the world. Bernard’s tastes in art had been modest and domestic. Robert’s tastes (as those of the next monied generation’s often do) ran to the sophisticated and scholarly; it was the great flowering of European modern art that excited him. Bernard’s heroes had been hometowners like Jesse Jones and Houston’s corporate kingpins. Robert’s hero was Leonardo da Vinci, the ultimate Renaissance man, the man who, in Robert’s words, “did everything—arts, architecture, military, engineering.” And that, interestingly enough, was the persona Robert took on as he came into power in his family’s company.

Upon graduating cum laude, Robert embarked on that all-but-obligatory chapter in the life of every boss’s son: “Proving Yourself Far From Home.” Everyone assumed he would join the family business; after all, hadn’t he worked in the stores since he had started marking shirts at age nine? Then there had been his precocious affinity for specialty retailing. Driven by the family chauffeur, young Robert had delivered eggs laid by the chickens on his family’s expansive North MacGregor grounds. When his customers asked why he had marked them up two cents over Weingarten’s price, he’d tell them they were paying extra for fresh-laid quality and door-to-door service.

Precisely because the world assumed he would join Sakowitz, Robert had spent a Hollywood summer “fiddling around with acting,” as he vaguely describes it. After college he headed to France, where he lived on the Left Bank, considered banking (too boring), and ended up at Galeries Lafayette, the great Paris department store. There he had what can only be described as a retailing epiphany. “I realized I was kidding myself. That the retail fashion business was the only business that covered every field I was interested in. Finance and economics, art and architecture, advertising, promotion, theater, administration, personnel, psychology, philosophy.” Just the sort of thing for a Renaissance man.

Next stop was Macy’s executive training program in New York, Bernard’s old proving ground. After two years a call came from Bernard: Sakowitz’s junior department was hurting. Did Robert want to tackle it? The offer was “sink or swim.”

Robert swam with facility in the pond of the Young Houstonian shop, increasing sales 57 per cent the first year and 37 per cent the second. It was Youthquake time in England, and Robert brought a fresh sensibility to the store. “He started a lot of activity that didn’t exist before,” says Gerri Halpin, who began staging Sakowitz style shows around that time. Robert’s tastes—the kind of clothes he felt would set a tone for Sakowitz—were already apparent. Halpin says that under Robert, the junior department “grew rapidly into not an age but a look, a way of dressing that was not the standard classics or the standard moderate dressing, but more avant-garde, more forward.”

Robert had a knack for the grand, attention-getting gesture. He organized the first-of-its-kind 1963 art gallery right in the store, hung with privately owned works by the likes of Cézanne, Remington, Klee, and Picasso, insured for a total of $8 million. Not only did the store’s visibility get a terrific boost, but Robert cut a high profile and quickly became a star, something his grandparents and parents had never been. When Bernard and Ann Sakowitz and Robert journeyed to England in 1964 to rustle up goodies for their Britannic Festival, the press was beside itself. Here were the Sakowitzes visiting Woburn Abbey, ancestral home of Robert’s friend Robin Tavistock, the Duke of Bedford’s son. Here were the Sakowitzes lunching at Claridge’s with Sir Richard Burbridge of Harrod’s. Now there was glamour! Robert obligingly painted a “word picture of the younger set” in London for one fashion writer: “the 3 a.m. parties, the dashes to Woburn Abbey for snow fights, ‘The Snake’—all movement in the shoulders—at Anabel’s, the little semi-fitted dresses, hi-bosomed with a low neckline.” Now there was hot stuff!

So was Robert’s “Bachelor Bob” incarnation. By 1967 the Houston Chronicle had named him one of Houston’s “Most Eligible,” noted his objections to golf (“lacks spontaneity”), and paid obeisance to the brick wall covered with paintings in his apartment at Château Dijon, Houston’s proto-swinging-singles complex. That was all good for the local image, but what put Robert on the international fashion map was the coup he pulled off in 1968: he moved heaven and earth to snare an exclusive U.S. opening for French designer André Courrèges’ new line of ready-to-wear.

French designer ready-to-wear didn’t exist in those days; American luxury stores like Neiman’s and Bergdorf’s bought French couture samples and had them knocked off. When Robert got wind that Courrèges, the iconoclastic inventor of the miniskirt, was planning to produce his own ready-to-wear, he moved quickly to premiere the clothes in Houston. He flew over and cajoled Courrèges in French; he touted Space City as the perfect launching pad for the futuristic couture; he helped the designer work out adjustments of fit and fabric for the American market; he even fended off a last-minute raid by Bonwit Teller’s formidable buyer, Mildred Custin. When Sakowitz’s Courrèges ad hit the New York Times, no less than Joan Kennedy phoned in her order. It was a brilliant maneuver, and Robert followed it up by negotiating a tricky exclusive for Yves St. Laurent’s new ready-to-wear line. For years Sakowitz had YSL boutiques when no one else in Texas offered these influential clothes.

Seventeen years later, now that YSL boutiques are breeding like prairie dogs and Sakowitz has seen many of its erstwhile exclusives evaporate, it’s easy to lose sight of what a milestone Robert’s early commitment to major-name French ready-to-wear was. He was one of the first American retailers to see it coming, and the first to have franchised designer boutiques in his store, a concept that would later gain such wide acceptance. At thirty, he had demonstrated remarkable powers of persuasion and an ability to work with designers, an edge that could make all the difference. And he now had a handy stick with which to beat Neiman’s—Neiman’s, which for so long had sewn up the top American lines like Galanos while Sakowitz had to settle for the rather less thrilling likes of Larry Aldrich. Finally he had created Sakowitz’s niche: the best, the latest European ready-to-wear. For years to come, the stores would be associated with such names as Valentino, YSL, Zandra Rhodes, or Zegna, the high-ticket Italian menswear designer.

The late sixties found Sakowitz still in an expansionary mode, albeit somewhat slowed from the frenzy of the fifties. The family had opened a third suburban store far westward in Town and Country Village, near the upper-middle-class haven of Memorial. This was the peculiar moment in Houston architecture when everything was supposed to look as if it came from another country and preferably another century. Accordingly, this latest, freestanding Sakowitz was a “Spanish Colonial Mediterranean” fiesta of wrought iron atmospherics from chandeliers to fake balconies. By this time Robert had graduated from stewardship over the fashion salon to executive vice president. The baton had passed to the Tobias-Bernard-Robert side of the family, which in 1965 bought out the interests of Simon’s heirs in the stores.

Robert’s 1969 marriage to Pam Zauderer thrust him—and the family, and the stores—onto a whole new level of visibility. From the moment Robert hid the engagement ring inside a Cracker Jack box at a Harvard-Yale game, it was the match of a publicist’s dreams. Pam, who came from a New York City real estate fortune considerably bigger than the Sakowitzes’, was a tall, striking young woman with long, dark hair and a high-profile look that one fashion journalist pegged as “rich hippie.” Her wedding gown was cowled and medieval; his groomsmen included S. I. Newhouse and Oscar Wyatt. Peter Duchin, brother-in-law of the bride, toasted Robert as “O serene cowboy” at the rehearsal dinner and played with two of his orchestras at the St. Regis Roof reception, for which 10,000 yellow roses were flown in from Texas.

After that auspicious beginning, the pair could hardly help becoming Houston’s In Couple. One read about Pam’s arrival with 32 pieces of luggage, her perfect size 6s, the leopard fur she had designed with the Zhivago-style shoulder closing. One learned of the difficulty of blending her African art collection with his African art collection in the cramped honeymoon apartment. Then came the move to the River Oaks house (the neighborhood had grown more tolerant with the times, and now both fourth-generation Sakowitzes, Robert and his sister Lynn, lived there); the People magazine photos of Robert and Pam reading their Sunday papers in bed; their election to the best-dressed list.

Robert’s various roles were coming into sharper focus as the seventies dawned. More and more in his interviews he was being portrayed—and portraying himself—as the Great Man of Taste. “Taste,” “style,” and “detail” were the buzzwords invariably linked with him. He was also emerging as “Mr. Robert,” the preserver and defender of the family retail legacy. Bernard, though recovering from a Denton Cooley triple bypass, was busy running the chamber of commerce. So it often fell to Robert to articulate the family’s determination not to desert downtown, its adamant opposition to going public, its romantic pride in being among the last of the family-owned breed.

He also took on the stepped-up battle with Neiman’s, since in 1969 his Dallas rival had opened across from the Post Oak store in the Galleria, which quickly became Texas’ premier mall. Sakowitz had already expanded its Post Oak store (Robert, applying his brand of imagery, draped the store in sheeting and invited customers to draw graffiti). But, as Robert concedes, Neiman’s had “resliced the pie.” You could argue that the wild success of the Galleria would draw more people to Sakowitz; you could also argue that Sakowitz would be overshadowed. You could turn one way off Westheimer to the store, or you could turn the other way to the Galleria, with Neiman’s and scores of specialty boutiques, many carrying the racy European apparel dear to Robert’s heart. For all the family’s vision in moving to the suburbs, now they would have to hold their own against competitors who were creating even plummier suburban meccas—a problem that has haunted Robert’s regime.

By 1975 Robert was running the Sakowitz show. He oversaw the first out-of-state expansion, and he played a role when Lynn Wyatt bought out the store interests of Bernard’s brother’s family, the Sacktons. (Although payments to the Sacktons come from Oscar Wyatt, Robert says the source of the money has been Sakowitz all along. Sackton disputes this, and he has lawyers looking into it.) Bernard finally made Robert’s position official by wrapping a gavel in a box and surprising him with it at a meeting.

The Hidden Corridor

What had he inherited? A modest chain of six stores and a boutique with $44 million in yearly sales—not bad, but not the big leagues. In the Houston market, where the lion’s share of sales were concentrated, competition was getting heavy, and an avalanche of slick, out-of-state stores was on its way. In 1974 Saks Fifth Avenue and Lord and Taylor opened near Post Oak, with Saks in particular trailing clouds of New York chic. In this spiffy new context, most of Sakowitz’s Houston stores looked dated, even dowdy. Some of the company’s systems were outmoded as well. Records were kept, as they had always been, on a cost basis instead of a retail basis—a system suitable for a much smaller company.

Robert set out to modernize things. After years of Bernard’s cautious approach to computer merchandise tracking systems, Robert wanted action. “We all begged him not to jump out in the middle, but he didn’t want to wait,” says a former executive who left on good terms. “Five years later he had to go back and do it the right way.” Robert also brought in new managers to work with and, in some cases, to replace the thirty- and forty-year men he had inherited from previous administrations. Unfortunately Robert’s top management team never really jelled. It is significant that the team he praised in 1982 as so “superb” was mostly gone three years later—not all of their own volition. And when Robert told a Women’s Wear Daily reporter last summer that part of the company’s troubles might have stemmed from “having the wrong people in the wrong place,” he stopped short of the obvious: that he had hired those people, put them in those places, and kept them there.

Middle management swelled under Robert’s regime; his ambitions for the company dictated beefed-up data processing, finance, advertising, art, and personnel departments. “He wanted to emulate bigger companies, but he couldn’t always afford it,” says one former executive. The results might be worth it (the personnel section’s thorough training program and attention to promotions are praised by current and former employees). Then again, they might not (a slick quarterly called the Magazine appeared briefly and vanished). “Basically Robert was susceptible to big ideas and sudden enthusiasms,” says another Sakowitz veteran. And another explains, “He’s a reactive person, a quixotic person, very enamored of new ways of doing things. If all of a sudden it felt right, he’d do it.”

Robert’s method of running the company was just what one would expect of a Renaissance man —he involved himself intimately with almost everything. Always a dynamo, seldom well organized, he operated in a ferment of activity: heading up buying trips to the shows in Paris or Milan, inspecting out of town real estate, leading buyers on horizon-broadening art gallery tours, and testing samples of his new men’s cologne, Rampage. Nothing that touched on the company’s image was too small to merit his attention. “Robert would spend hours pondering the color of the changing rooms for a new store,” says a former associate. That’s the kind of criticism that seems to wound Robert the most. “The attention to detail that was extolled while we were successful and growing is now damned,” he protests. But the problem was obvious: it was impossible for the CEO of a mushrooming empire to go on being the Renaissance man, exercising authority in all matters of taste.

Though Robert says he dislikes meetings, people on his staff would be surprised to hear that. Having seen President Ferdinand Marcos’ hidden corridor at the palace in Manila, Robert had had a similar one installed on the third floor of the downtown Sakowitz; it enabled him to pass unhindered among several simultaneous meetings. “There were so many meetings, and he was always the head of them,” remembers one former associate. “He traveled a lot, and generally meetings didn’t happen when he wasn’t there, or they would be inconclusive. People were constantly waiting his return.” Recalls another onetime staffer, “We couldn’t decide on the wall-coverings for a new store until he came back from Europe.”

From all accounts, that atmosphere did not foster a strong hierarchy. “Robert was not one for developing the strengths of people,” remembers one Sakowitz veteran. Recalls a second: “People were frightened to make decisions because he’d come back and say, ‘Why did you do this idiotic thing?’ ” A third says, “Robert could intimidate the hell out of a lot of people.” There was no Bernard around to question Robert’s ideas strenuously. Among the few employees willing to go up against Mr. Robert was Irving Weiner, the company vice chairman and longtime money man. “Never in an open meeting, of course,” qualifies a former Sakowitz executive. “Occasionally you would hear his and Robert’s voices raised behind closed doors. Once I heard Irv tell him, ‘You can’t spend any more money, period.’ ”

But if it was frustrating to work for Mr. Robert, it was also exhilarating. His great gift was communicating to employees the sense of high adventure he felt about the company and where it was going in the retail world. The deep, mellifluous voice that seemed as if it came from a much taller man; the nonstop torrent of smart, sophisticated talk and new ideas; the famous charm—all contributed to what employee after employee describes as Robert’s “charisma.” He drew you in, whether delivering a monologue on art history in a London taxicab or throwing around extravagant ideas for the stores’ latest festival. He still inspires an astonishing ambivalence in associates who have exited under good circumstances and bad. Many of them concur about his flaws, but they return again and again to the extraordinary sense he gave people that they were part of something electric, something special. They willingly confess to having been under his spell.

As befitted an intellectual, Robert turned his Ultimate Gifts—Sakowitz’s answer to Neiman’s legendary His and Her Gifts—into conceptual presents. Starting with the so-called Gift of Knowledge in 1974, the emphasis was on services, more than things: conversation lessons from Truman Capote, piano lessons from Peter Duchin. It was a PR bonanza; with Stanley Marcus on the brink of retirement, Robert became “the Texan with the catalog.” Even a misfire generated acres of print: when the 1978 catalog offered “a $94,125 “dinner party for twenty-one of your worldly friends. Like Walter Cronkite, Neil Armstrong, Senator Henry Jackson. . . .” Cronkite objected, and Jackson fumed.

Robert’s image-building was hardly confined to catalog stunts. He was the wine connoisseur who brought a groundbreaking wine auction to his store; he was the young thinker at Washington economic conferences and on the Today show; he was the man of consequence who in a single day went from Paris, where he was arranging for French president Giscard d’Estaing’s presence at a Sakowitz festival, to New York and back to Houston, where he helicoptered dramatically into the Post Oak parking lot in time to play host to a group of British peers. Robert loved to proclaim that as a specialty store, Sakowitz embodied “the quality of being special.” As the seventies wore on, it sometimes seemed that few things were more special than Robert himself.

At the same time, Robert’s penchant for pontification was finding full expression as company programs were dubbed with the portentous acronyms he favored. Other companies might have annual departmental reviews; Sakowitz had the GAR, or Goal Achievement Review. Other companies might have full-sized stores, mid-sized stores, and boutiques, but Robert labeled his stores “Alpha through Epsilon.” The most famous example of Robertspeak was the IDA merchandising concept he dreamed up in 1974 and then spent $1.5 million to develop. IDA stood for the three types of Sakowitz customer: the Innovational, the avant-garde, cutting-edge client, pegged at 7 per cent of Sakowitz’s market; the Directional, the customer who followed the latest trends, estimated at 29 per cent of Sakowitz’s clientele; and the awkwardly named Acceptational, sometimes translated by a bewildered press as “Acceptional,” cautious souls who only buy a style after it’s accepted, comprising 64 per cent of the client mix. The IDA rationale of buying, displaying, and selling merchandise was thoroughly drummed into employees. The idea was that it should be self-evident to the customer which section of the store contained merchandise that appealed to the I, the D, or the A in her—or him. Unfortunately the execution of the IDA concept was not always as lucid to others as it was to Robert. While one former executive lauds the concept as “brilliant,” another staffer confesses that “I never really understood IDA.” Certain waggish employees took to calling it “the IUD of creativity.”

For all his stress on innovation, Robert seemed unable to shake his past—to shrug off the stores’ broad streak of mainline stodginess. The Europeanization of the store’s upper-end merchandise was an ingenious idea (and one for which Robert, likening himself to the prophet who goes without honor in his own country, felt he never received sufficient credit), but it was a graft that never entirely took. There was always an unresolved tension between Robert’s innovative vision of Sakowitz and the image of the conservative, old-line Houstonian’s store that lingered in the public mind and often in the stores themselves. It resided in the culture clash of a fusty sport coat and a zoomily fitted Italian jacket, the contradiction of anachronistic granny hats and Kenzo separates.

Family tradition had decreed there would be no mandatory retirement, so the stores were generously peopled with what one executive fondly, but ruefully, calls “three-hundred-year-old ladies.” They had built that cradle-to-grave service Sakowitz made its name on. It wasn’t that they were incompetent or unable to adapt (witness the doughty Miss Crystal, long a mainstay of the downtown fashion salon, who when duty called stiffened her upper lip and fitted a transvestite shopper in a marked-down Zandra Rhodes). But these elderly staffers made the stores seem more staid than they were. So did the physical plants in Houston: the downtown store was in a time warp, Post Oak faceless, Gulfgate unglamorous, Town and Country an outmoded fad. Put it all together, and you got image schizophrenia.

Sakowitz’s proliferating store formats were not always readily grasped, either. By 1978 Robert was making moves to expand the chain rapidly. It had taken 25 years for the company to expand from one store to six; now, in just six years, Robert would more than double the number of units from seven to seventeen. Some were full size; others were smaller “Sakowitz IIs,” under 100,000 square feet with a more limited selection of merchandise; still others were different types of boutiques located in a variety of settings, from hotels and office buildings to shopping villages. Ambitious, surely, but hard for the public to keep in focus. A Sakowitz was not a Sakowitz was not a Sakowitz. Even Robert’s trademark cutting-edge European fashions didn’t appear in every store.

Rapid expansion also vastly complicated Robert’s tendency to get involved in everything. His travel increased geometrically. There were locations to pick, endless decisions of taste and style to be made. After opening modest but modern new stores in Houston’s far north FM 1960–Champions area and the far east NASA area, Robert began to mastermind out-of-town stores that lived up to his glamorous image of the company. The Dallas store that opened in 1981 was a gorgeous showcase of pink marble and rich, sleek woods, due in no small part to Robert’s fastidious attentions. He went to President Marcos’ Philippine quarries to pick the exact shade of marble he wanted. He chose the artwork from his own collection, including canvases by such provocative painters as John Alexander. To the extent that Robert really does have taste, all this was to the good. To the extent that he was spreading himself awfully thin, all this boded ill.

Robert’s acrimonious 1978 divorce from Pam was the only blot on his dynamic media image in those days. The contest had turned into a very public spectacle after Pam’s legal pleadings alluded to a wiretap placed on her phone and asked the court to bar testimony about the wealth of Tony Bryan, whom she later married after his divorce from Houston heiress Josephine Abercrombie. Accustomed to years of basking in adulatory press, Robert, the man born to be in the newspapers, was seeing the underbelly of publicity. Bad things could get in the papers too. He found it maddening, and still does: people readily believe negative publicity, he insists, but they don’t believe the gush.

“We Were on a Roll!”

Two years later, Robert was back on top of the media heap, enjoying a warm bath of worshipful coverage. Houston’s oil-fueled economy was in overdrive during the heady years of 1980 and especially 1981, when Sakowitz profits hit an all-time high. Sure, expansion consumed cash, but cash flow was no problem. “We were at a pinnacle, we were on a roll!” recalls a former executive. Robert waxed expansive to the press. “When you are innovative with a great deal of taste, you provide an experience for people that’s part of the higher human experience,” he told a reporter. “It’s like an art form—it gives the human psyche a sense of happiness, well-being, an escape from the humdrum of human experience.” It was hard to believe he was talking about, well, shopping. Robert wasn’t the only one who felt beatified; the euphoria affected even the Sakowitz lifers. One manager, fretting aloud over a problem, was told by an elderly company veteran, “Stop worrying. Enjoy this. You’ll never see this kind of thing again.” Says one departed executive, “There was no tomorrow. There was the feeling that if there were mistakes, the growth in volume would take care of them.” He might as well have been talking about the oil patch. The danger was in growing overconfident. “We retailers couldn’t get out of our own way from 1980 to 1982,” says one Houston retailing executive. “Volume covers a multitude of sins, and it covered Robert’s.”

Oil fever was at its height, and that could only have served to strengthen Robert’s late-seventies resolve to locate stores in energy-related markets of the Southwest. That strategy, says Robert, “sprang from the fact that Houston had been energy-oriented and had served us very well. During the recession of 1970, Houston was relatively unscathed and we grew rather substantially, so I looked to the anti-inflationary, anti-recessionary character of primary industry.” Of course, energy-related industry turned out to be all too recessionary, but even as late as January 1982, with the rig count dropping, it would have been hard to find anyone in Texas warning expansionists to put on the brakes. Robert’s rampantly bullish mood could only have been reinforced by the people he was talking to or keeping an eye on—oilmen like his friend John Mecom, or his brother-in-law energy czar Oscar Wyatt, or the local bank establishment.

All of retailing seems to have been seized with an “expand or die” frenzy in recent years, and to a degree Sakowitz was expanding for the same reasons everyone else was. Robert cites a variety of factors that impel retailers to grow. One is to put the company in a better position with vendors, whose message is basically “buy more or we give the ads and the advantages to someone else.” Another impetus to boost sales volume is to cover increased operating costs based on inflation and rising wages—particularly important since the advent of the minimum wage in the late sixties. A third impetus, he says, is the concept of social mobility that followed the education of the baby boomers. “When you have tremendous social mobility and full employment, how do you keep people if you don’t have places for them to move up the ladder?” he asks rhetorically, quoting economist Thorstein Veblen on rising expectations.

Another powerful lure to expand was Robert’s growing interest in making real estate deals with developers who were building and financing his new stores. He put up $675,000 to become a limited partner—as Robert Sakowitz, not as Sakowitz, Incorporated—in Tycher Properties’ Sakowitz Village in north Dallas, a tile-roofed, open-air shopping cluster styled after a Mediterranean hamlet. He also invested personally in the Kensington Galleria, Tulsa’s scaled-down version of Houston’s famous mall, where he intended to open another branch of Sakowitz. In both cases, Robert went to the developers to cut the deals, which were appealing because he would be able to influence the aesthetics of the centers. He would also have a chance to make money. Robert has never had a great personal fortune; most Sakowitz money has been tied up in the stores, although the prerogatives of family ownership allowed for a rich lifestyle. Compared with his exceedingly rich brother-in-law or friends like Imperial Sugar heir Shrub Kempner, Robert has always been sort of the poor boy on the block. Linked with his burgeoning retailing empire, Robert’s real estate deals could make him richer, or at least give him some tax breaks.

It was a unique moment in the region’s economic history, perhaps the only moment when a family-owned company with limited resources could have found the financing to expand so far, so fast. Stanley Marcus hadn’t been able to do it back in the sixties, hadn’t even tried; one reason Neiman’s sold out to Carter Hawley Hale was that the family-owned company could no longer support the expansion the Marcuses had begun. In Texas in the late seventies and early eighties, though, Robert had found he could have the romance of family ownership and expansion too. One of the joys of private ownership, he told a reporter at the height of his 1981 glory, was that “we don’t have to worry about, say, quarterly reports to shareholders, or their disapproval. With this type operation, you can be a maverick, a very daring maverick, and get away with it.”

Or fall flat on your face, which is what Robert Sakowitz proceeded to do.

The Fatal Mix

The descent was swift from 1981, when it appeared that Robert could do no wrong, when his grin beamed out from glossy magazines and his pronouncements issued forth like tablets from the Mount, to 1982, when oil prices plummeted and—horror of horrors—the peso was devalued in June. That was a particularly cruel blow for the Post Oak store, which accounted for a large proportion of the company’s sales. The Galleria was a major North American shopping mecca for rich Mexicans; directly across the street, the Post Oak store had made a point of offering doting service to these well-heeled visitors. Then, overnight, they were gone. “It was like someone had put a wall up in front of the door,” says a former salesman.

Soon, with spending power dwindling in its markets, Sakowitz was caught with extra inventory—as were many other Texas retailers. That meant more markdowns, lower sales figures, less cash. Whenever cash flow is disrupted in retailing, it’s bad news, but it’s especially bad news when a company is headlong into a cash-hungry expansion program and heavily into the banks—which Sakowitz was to the tune of nearly $30 million, having refinanced the company’s debt in 1982. Now Robert had far less room to see what would fly in new markets.

There was cause for alarm at this point, but Robert—his natural optimism and Houston-Texas-Southwest bullishness intact—listened to the conventional wisdom of Houston’s business community. “Most people thought it was a transitory thing, that the economy would come back in 1983 or more probably 1984,” he says. Conglomerate-held chains like Bloomingdale’s and Neiman’s had their eggs in a variety of geographical baskets; with their huge assets they could afford to hunker down and wait. Sakowitz’s fortunes were wholly on the line—but Robert took comfort in remembering that Sakowitz had weathered hard times in Houston before.

Instead of trimming his sails, he forged ahead with plans to open a store in Tulsa. He kept looking into more new markets. He even popped for expensive architectural plans for a high-rise office and hotel complex he wanted to build on the Post Oak site—never mind that the Houston office and hotel market was saturated. It was his own private castle-building. Significantly, the plans included an aerial walkway that would link the Post Oak site to the Galleria—the first tangible sign that Robert needed the Galleria, even if the Galleria didn’t need him.

By 1983 Robert had a parting of the ways with his general merchandise manager, in most retailing operations a key figure who supervises divisional managers and has final say on the buying plans. True to form, Robert took on some GMM functions himself, and true to form, he revamped his management structure into the grandly titled IMT, or “Integrated Marketing Team.” One reading of the IMT is that it was an innovative attempt to cut down on bureaucracy. Another is that it was an attempt to make lemonade. It is almost unheard of for a fashion chain to go without a general merchandise manager, but Sakowitz did for more than a year. Robert finally hired one seven months ago.

The worst of it was that Robert had leveraged himself into a position where he no longer had any room for mistakes. By mid-1983 the company had made what Robert has termed some “bad buying decisions” on goods it had to keep marking down to sell. That meant less income, which led the store to cancel some of its fall orders. It was the beginning of the vicious circle that ultimately did the company in: a fatal mix of rumor and poor cash flow. By the fall of 1984 vendors wanted cash before they delivered their goods. The more rumors got around about trouble, the more wary merchants became about delivering without payment. Sakowitz’s cash flow problem worsened, less merchandise arrived, there was less and less money to buy more. Merchandise had to be spread thinly among the stores; sparsely stocked stores are slow death. The downward spiral was exacerbated by energy-depressed markets and the tooth-and-nail competition in Dallas and Houston, where out-of-state retailers like Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s were still elbowing into the marketplace and the discount-mall phenomenon was aborning.

The vicious cycle guaranteed that the new Sakowitz stores wouldn’t do well. Lots of other variables have been proposed to explain the company’s problems in its new markets: Whether Robert’s decided preference for freestanding stores was appropriate for the Texas climate or even for modern life. Or whether the cities he chose were the right size, or the parts of town he located in the right ones. Or whether the stores in Tulsa and Midland were the size that Sakowitz should have been shooting for (Stanley Marcus, by way of comparison, says that Neiman’s has “avoided the temptation of putting in smaller stores,” feeling the firm couldn’t represent itself properly in stores of less than 100,000 square feet). Those are all interesting and debatable subjects, but we will never really know how well the new stores might have done because for most of their short lives, they were too poorly stocked to prove anything. The one in Dallas, for example, got through the advent of Bloomingdale’s and for a time had the best gross margin of any store in the company. But as one top Dallas manager put it, “There was never enough merchandise. We could have done okay business if we had had the inventory.” One employee told Women’s Wear Daily that the Midland store had fallen upon hard times by 1983, a year after its debut. The trade bible also reported that following in-store trunk shows (at which clients ordinarily view and special-order certain lines), desperate Midland staffers submitted fictitious orders to headquarters as a primary means of obtaining merchandise.

Larger questions about the company’s merchandising strategy—whether private label was too great a part of the mix, whether too much attention was devoted to Robert’s beloved high fashion and not enough to the moderately priced clothes that were the stores’ bread and butter—may have contributed to the company’s difficulties, but if Sakowitz hadn’t been so financially overextended, today it might only be struggling instead of bankrupt.

As thin as things were getting in 1983, Robert was neither cutting back on his expansion plans nor regrouping on the Houston front. It had been apparent for some time that the downtown store was ailing (as was the downtown retailing scene itself), but Robert was reluctant to put the old family flagship out of its misery. By the end of 1983 he had begun studies aimed at reducing the downtown store to one or two floors. That was as close as he ever got to cutting his losses in Houston, even though the Gulfgate store was foundering and all the rest (except for Champions) were looking more and more like yesterday’s news.

As Robert described it, 1984 turned out to be “the worst year in the history of Sakowitz” (before 1985 turned out to be “a year of hell”). The company had losses of $3 million on sales of $120 million. The Tulsa store opened, stocked with an inventory purchased at least in part with a $3 million loan from the developers of the Tulsa Galleria, the Williams brothers. One might have thought that with things going so poorly, Tulsa would have been the end of the expansion, but no: Robert was signing a contract to build a new store in Austin and looking at the possibility of opening in San Antonio. He was also engaged in an intense courtship of Laura Harris, 26, a blue-eyed blonde from Deer Park, a working-class suburb of Houston. They had met when she was out with Robert’s young nephew, Steve Wyatt. The romance, with its whirlwind trips and a head-to-toe outfitting in Sakowitz’s fashion salons (“This is like a fairy tale for a girl from Deer Park,” Laura told an acquaintance), divided Robert’s attentions when the company was having its most difficult year. It was ironic. Here he was, ready to settle down after a succession of blondes on the bachelor circuit, but his timing was all wrong.

By summer, Laura had converted to Judaism and the two were married by a prominent Houston rabbi. And also by that summer, Sakowitz stores were overstocked with merchandise that wasn’t selling. The Post Oak staff was in turmoil by August, with personnel shifting constantly. Sakowitz had had an unusually stable roster of buyers; now they were turning over as rapidly as they did in the big, publicly held chains. By the fall it was obvious that merchandise wasn’t being delivered; there were empty spots that clever rearranging couldn’t hide. Buyers were spending more time urging reluctant vendors to ship than they were on deciding what to purchase.

The New Age of Banking

As bad as things were in the stores, it took a death struggle between Robert and his bankers to send the company over the edge. In late fall, with rumors of Sakowitz’s troubles sweeping the city, Robert began negotiating for a new $27 million credit agreement with his five-bank group of lenders, led by Chase Manhattan. Since October, he had had trouble meeting all the terms of his loan agreement. Incredible as it may be, in January Robert announced that a new store in Austin was to be built by the Trammell Crow Company, a move that did not inspire enthusiasm among Robert’s nervous bankers. He kept on discussing stores in Little Rock and New Orleans with potential investors. In March Robert announced a new line of credit, blamed rumors for his woes, and assured the press all was well. It wasn’t. As a condition for waiving payments on his short-term loans, the banks were requiring him either to take on long-term debt or to find equity investors, people who might give Sakowitz a cash infusion in exchange for stock.

It was all part of the tight new age of banking, and Robert found himself caught in its vise. “In 1975 there wouldn’t have been the same kind of insistence on the immediacy of cash infusion,” he says. But with new banking bills passed in 1981 and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency cracking down on banks, there were no longer loans available to retailers based on their assets. Suddenly cash flow was king, and cash flow was what Robert didn’t have. He had been talking about the coming financial revolution for years in his public speeches. “The problem is,” he says, “I did not know how to extricate myself from my own predictions.”

As the spring wore into summer, Robert found no long-term loan agreement. Lending institutions, looking at Sakowitz’s condition, Houston’s depressed market, and the 14 million square feet of retail space added there since 1983, told Robert to “come back and see us in 1989.” For many of the same reasons, equity investors were not growing on trees. In any case, that option must have had limited charms for Robert, who for so long had been answerable only to himself. Equity investors have a nasty habit of wanting as much control as they can get for their money—having a say in operations, sometimes even 51 per cent of the voting stock. Why, that could be as bad as being publicly owned. A source close to one negotiation between Robert and potential investors put it this way: “He was unrealistic. He didn’t want to give up what was involved, even though he desperately needed an equity investor.”

As to selling the company outright—how could Robert Sakowitz do that with the family ghosts peering over his shoulder? Hanging on to the stores was not only a matter of ego—it ran in the blood. Simon had worked until the last weeks of his life; Tobias had insisted on one last wheelchair tour of the stores before he died; Bernard had attended the Champions opening with his oxygen and his nurse. How could Robert, at the age of 47, resign himself to losing the stores?

By now, everyone in town seemed to be gossiping about l’affaire Sakowitz. By far the favorite rumor was that Oscar Wyatt either would or would not bail out his in-laws’ company. “I didn’t contemplate asking him,” says Robert. “I’ve grown up in the throes of problems between members of families, and I’ve seen how destructive they can be. If the involvement could have come from an outside third party, to me that would have been more appropriate.”

Those family problems—an old rift between the Tobias heirs and the Simon heirs—had led to a wrangle over the Post Oak site that couldn’t have come at a worse time for Robert. The Simon side, led by Gaylord Johnson, Jr., no longer owned an interest in the store, but together with the Sacktons they controlled Post Oak Center, Inc. (POCI), the company that leased the site from the Osborne family. If the Osbornes wanted to sell the long, narrow corner of the plot that ran up Post Oak to Westheimer, they had to give POCI rights of first refusal on the strategic strip. When the Osbornes came up with a buyer in 1978—Frank Hudson’s Cadillac Properties—the Johnson faction, ignoring Robert’s wishes, declined to exercise their right to buy the land. Robert and Lynn Sakowitz Wyatt then tried to buy POCI’s refusal rights, but their relatives set a price too high for them. It was the culmination of years of friction between the side that wanted to plow all profits back into the stores and the side that was interested in earning dividends. Finally Robert tried to buy the corner directly from Cadillac, but the deal didn’t come off. In 1984 POCI’s lease was up, and Cadillac was free to build. So a year later, in the summer of his discontent, Robert had to watch Cadillac’s three-story, French chateau-style Embassy Plaza shopping center rising athwart his Post Oak store, cutting off the view of Sakowitz from Westheimer and compromising his hopes for developing the site. It was impossible not to read Embassy Plaza as a symbol: Robert backed into an increasingly untenable position.

All through the interminable summer, Robert and his lieutenants were at loggerheads with the banks. On April 15 the company had made a $1 million payment on principal; another was due in August, and the banks made it clear there would be no more waivers on defaults. In June Sakowitz told the banks that he would have a new business plan in three weeks; once again he asked for an extension. But during July it became clear that the center could not hold. The fall catalog was on the press, but vendors were holding back the goods; the press run had to be postponed while Sakowitz staffers mounted a phone blitz to remind the vendors of their long relationships with the company. In mid-July the jewelry franchise pulled its wares out of the stores, charging late payments and sundry breaches of contract. More and more vendors were putting Sakowitz on a C.O.D. basis, and the banks would not honor the foreign letters of credit that enabled the stores to purchase imports and private-label goods. Then, on July 23, the banking group called in Sakowitz’s $26 million note and, one day before payroll, seized checking accounts worth at least $1 million as collateral. Robert made his payroll—paid it in cash—but the bank’s action put an end to his long juggling act.

As Robert’s camp worked furiously to find a way out, two events created an odd resonance. On July 25, just as the banks unleashed their thunderbolt, a news account of Lynn Wyatt’s Indian-theme birthday party in the south of France ran in the Houston Chronicle. “The party of the Season,” New York gossip columnist Suzy Knickerbocker called it, dwelling on guests like the Henry Fords II, the Begum Aga Khan, Gerald Hines, and Estée Lauder. Lynn wore eighteenth-century Indian prince’s garb by Karl Lagerfeld; Oscar Wyatt, all in white, wore an Indian dagger and a gold turban. Several days later, in Houston, a more somber gathering took place: old Sakowitz employees buried Lester “Frenchy” Hanff, a longtime company stalwart. “A lot of old-timers were at the funeral, twenty-, twenty-five-, thirty-year people who had built the business,” recalls one mourner. “I felt like I was at two funerals. It was the eeriest feeling of my life. Irv Weiner looked terrible. Robert looked terrible. Irv had to rush right back to the attorneys’ office. Everybody knew it was coming; the only question was whether it would be this week or the next.”

Just days later, on August 1, the company announced that its board had voted to try to keep family ownership by filing for Chapter 11 protection against hundreds of unsecured creditors. “Some people are furious because they think we planned to leave them holding the bag,” says Robert. “We in fact did exactly the opposite. There was no war chest in reserve. We were still negotiating with investors the day before Chapter Eleven was declared.” Nothing came of those discussions, though, and offers from suitors like Allied stores, parent of Joske’s, and other outside investors were still deemed unacceptable. The stench of failure might be mortifying, but Chapter 11 was also a way to get out of long-term contracts in Tulsa, Dallas, Midland, and Austin. The developers of the Dallas shopping village and Austin mall where Sakowitz located say Robert had begun keeping them apprised of what was happening, although a spokesman for Trammell Crow’s Austin office says, “We knew sales were way down, but we didn’t have any idea of the magnitude of the problem or we wouldn’t have made the deal.” Crow was left with a completed store shell and after three months signed a new tenant.

The prominent Williams family of Tulsa, who, with other investors in the Kensington Company, developed the Kensington Galleria mall, had an even bigger headache. It had been only a matter of months after Sakowitz’s gala Tulsa opening in 1984 that rumors about the company’s stability began to fly, hurting the mall’s leasing efforts and its traffic, according to John Williams, Jr. Nor was Kensington—to which Sakowitz was $3 million in debt—kept up to speed on the company’s problems. When the $3 million loan came due on April 15 of this year and Sakowitz needed an extension, “that’s when we started to get information,” says Williams. Kensington agreed to grant extensions as long as Sakowitz’s bankers did. They learned of the possibility of Chapter 11 proceedings “forty-eight hours before the filing, and only because we confronted them with a rumor and they admitted it [was a serious option],” says Williams, adding that “they’re going to tell us, or anyone, as upbeat a story as possible to avoid a self-fulfilling-prophecy phenomenon.” Very shortly Kensington found itself Sakowitz’s largest unsecured creditor. It bought out the Tulsa Sakowitz, inventory and all, and changed its name and management so as not to have a lame-duck store in its mall. Robert is still a limited partner in the mall, but Williams says if the three million isn’t ultimately repaid, it voids the value of that partnership. Relations with Robert? “Not adversarial, any more than you might expect with someone who owes you three million dollars and can’t pay,” says Williams dryly.

Tycher Properties, the developers of Dallas’ Sakowitz Village (renamed Village on the Parkway), still list Robert as a $675,000 limited partner in the complex. But—in the unkindest cut of all—they promptly hired none other than Stanley Marcus to help them find a new upscale tenant for the empty Sakowitz store that was the jewel in Robert’s crown.

Once the deed had been done, of course, Robert brought his own inimitable style to Chapter 11. Immediately one of those lofty concepts sprang forth. Sakowitz was going to “Return to Our Roots,” a polite way of saying that most of the out-of-town stores would close. Stores that were to close were “Sunset Stores.” The four Houston stores that were to remain open were now “Sunrise Stores.” News cameras clicked as Sakowitz employees planted an oak tree at the Post Oak store to express their “deep-rooted” support of Mr. Robert, who was photographed in tears. He ran a sentimental open letter in the newspapers and received an outpouring of sentiment in kind. The letters to the editor, the personal notes mourning the loss of an institution, all seemed to hark back to the simpler, more comforting Houston of which Sakowitz had once been a true reflection.

Amid the expressions of support, however, was a terrible irony: there was precious little in the stores for supporters to buy. Even Post Oak was a desert of empty stretches and barren shelves on the ground floor, where large sections were shut off by foam board and big vitrines held four or five handbags huddled together to give an illusion of plenty. It was downright spooky.

Chapter 11 Etiquette

Robert’s sentimentality over the turn of events did not prevent him from exercising what one might call bad form in the new etiquette of Chapter 11. For one thing, scarcely three weeks after the filing, the local gossip columns twittered that Robert and his bride had just bought a big new mansion on River Oaks Boulevard, which doesn’t look so hot when your loyal, oak-planting employees are about to lose their livelihoods. You might as well take out an ad reading “Not personally liable for my company’s debts.” Robert tried in vain to keep the new house under wraps, insisting to a television interviewer right before the story broke that he and Laura were “just looking.”

Documents filed with the bankruptcy court raised many eyebrows. Although Robert reported deferring $80,000 of his $200,000 salary in 1984, how about those “reasonable and necessary business expenses,” like nearly $25,000 for Robert’s domestic help, landscape maintenance, and Laura’s travel, or nearly $30,000 for similar help at the home of vice president Ann Sakowitz? That was family ownership for you, but it still looked unsuitable. And then there was the strangely indifferent treatment of employees that caused an uproar among Sakowitz alumni. They buzzed in dismay about the lifetime stalwart who returned from sick leave only to be informed by the personnel director—not Mr. Robert himself—that it was time for early retirement. One highly regarded couture saleswoman who had extolled the company in post–Chapter 11 articles found herself being asked to go on commission as Mr. Robert sat silently by. No one says it’s easy to cut a staff; no one says it can’t be done with sensitivity, either. Such conduct resurrected anecdotes about close associates who hadn’t heard boo from Robert during serious illnesses. Said one such disillusioned veteran, “If people were devoted to him, it certainly wasn’t because of the care and feeding he gave employees. He was selfish.”

The first interview Robert gave Women’s Wear Daily after the filing struck people as impolitic, as well. “He was rapping everyone in the world for his troubles but himself,” says one Houston retailer. “Here he should be coming on bended knee to the market for goods, and he’s rapping the market for spreading rumors about him.” It was less impolitic to blame the banks, which Robert and his camp did most emphatically. “Unbelievably intransigent” is how Robert describes the banking group that called his note. A Sakowitz associate complains bitterly about “the way the banks can brutalize you.” He argues that the banks jumped the gun, that it would have served them better not to “destabilize” the company; banks were all too eager to lend money back in the oil boom, he continues, and now it would behoove them to try to see their debtors through. When lending institutions invest in their debtors, they do, in a way, become their partners. It’s a complicated judgment call to decide when a loan goes bad. But facts were facts, and no matter how misused Robert felt, he couldn’t escape them. The starkest fact was this: Robert had reneged on his loan agreement when he failed to make his payments. How much simpler could it get? Yes, banks could go easy on him—if they wanted to; if they had confidence in him; if they thought the company could pull through. But if they didn’t, they could pull out. That was their right, and that was their call.

Now Robert has thrown in his lot with New York’s Chemical Bank, which will supply an immediate $8 million loan to help bring in the major influx of goods he requires. The chain’s “Unthinkable Sales” at the stores that would close generated cash, but even with Sakowitz’s new credit line, things will be tight. That $8 million loan would not even fill the Post Oak store, and there are three other stores to fill; $8 million will go only so far. But that hasn’t daunted Robert, who is planning open houses to launch his Christmas season and a new campaign—“Today’s Sakowitz Is You.”

Aside from cash, the problems that remain are those of perception, and no bank can help him with the store’s image. In retailing, perception is everything—to vendors wondering whether it’s safe to extend credit; to customers sniffing to check for the smell of death in the air. “People like winners,” says a retail developer. “When it comes to the high-fashion shopper, one thing counts: is she proud to carry the bag?” The most striking of this story’s many ironies is that Robert Sakowitz, for whom taste is everything, is now left with the least stylish and most neglected of his stores. They were last on his list of priorities when he was busy expanding; now they’re all he’s got. Robert says all these stores are profitable, but you have to wonder why. The Town and Country store has all the flair of a La Quinta lobby, and it’s now on the wrong end of the shopping village, away from the big new mall containing Neiman’s and Marshall Field’s. The Sakowitz directly across from NASA in the Ports O’ Call mall, while attractive inside, sits in a mall from which all tenants but one lonely optical shop have fled. Two dead palms flank the front entrance, and on a recent Saturday, seventeen cars sat in the parking lot while not five miles off, thousands of shoppers thronged the Macy’s at Baybrook Mall.

Even the Post Oak store, now the flagship, has a patched-together quality. It’s showing signs of life compared with its grim September state; the burned-out light bulbs have been replaced, a new coat of paint has spruced things up, and pretty holiday clothes have been brought down to the first floor. The chic LeNotre pastry and chocolate boutique has hied itself elsewhere, though, and large areas of the store remain partitioned off. Robert Sakowitz, the man of parts who never quite put all the pieces together, still has a lot of pieces to pick up.