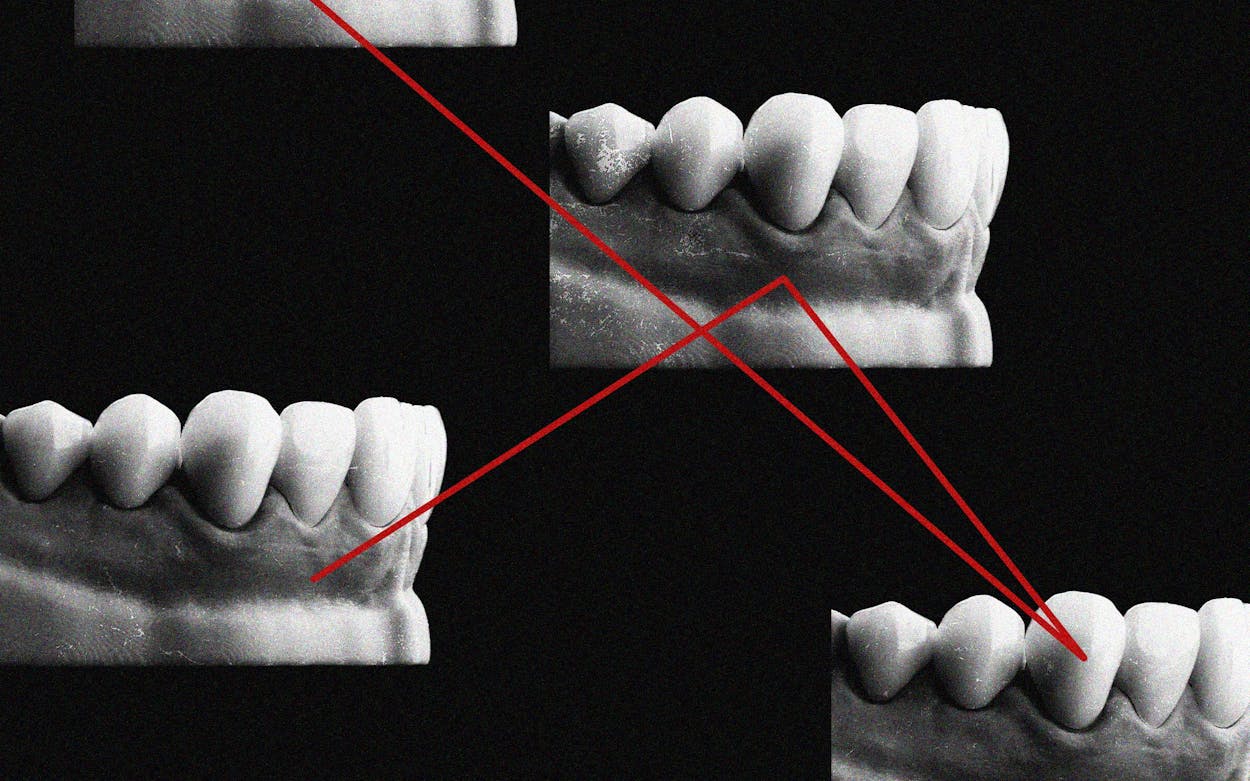

There aren’t many good guys in Chris Fabricant’s recent book, Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System. It’s an often-bleak story of innocent people going to prison because of bogus forensic science—bite mark evidence, flawed arson analysis, faulty hair comparisons. The book chronicles the journey of one innocent man in particular, Steve Chaney from Dallas, convicted of a 1987 murder on bite-mark evidence. Two forensic odontologists testified that a mark on the victim’s arm was made by human teeth—and one of them said the odds the bite mark belonged to someone besides Chaney were “one to a million.” Chaney spent 28 years behind bars before he was freed in 2015 after Fabricant and the Innocence Project (the New York-based nonprofit for whom he works as director of strategic litigation) began working on his case.

If the book has a hero, it’s Lynn Robitaille Garcia, the general counsel of the Texas Forensic Science Commission, a state policy group founded in 2005 to, essentially, help stop convicting people on outmoded or flawed scientific methods. The FSC was one of the first such commissions in the country, and Garcia has been guiding it since 2010. Today it is widely recognized as one of the most authoritative forensic science institutions in the country.

Garcia has led the FSC through several controversies, the worst coming not long after she was hired. It involved the 1992 conviction and 2004 execution of Cameron Todd Willingham for setting a fire in Corsicana that killed his three children. In 2009, the FSC was about to hold a meeting at which a national arson expert was going to testify that the court’s finding of arson “could not be sustained”—in other words, that Willingham was wrongly convicted and executed. But days before the meeting could take place, Governor Rick Perry fired three commissioners, ending the investigation and causing a national uproar.

The politicized aftermath made the FSC, in the word of one commissioner, a laughingstock, until it released an 893-page report in 2011, under new general counsel Garcia’s leadership. The report was, to the surprise of many observers, decidedly nonpolitical, refusing to speculate one way or the other on Willingham’s innocence and also refusing to point fingers at the arson investigators, saying that they were merely using the accepted science of the early nineties. The FSC, the report said, “was established to advance the reliability and integrity of forensic science in Texas courts.” Period. Garcia, Fabricant writes in his book, deserved a lot of the credit for the way the FSC carried itself: “Garcia believed in the Commission’s basic mission: ensuring the scientific integrity of forensic evidence used to make life and liberty decisions.”

One of the FSC’s high points came in 2015, when it held a meeting on bite-mark evidence and Chaney, recently released because a court threw out his conviction, sat as an observer alongside Fabricant. Chaney got to hear Fabricant tell Garcia and the commission that bite-mark analysis was “an entirely subjective technique,” and he got to hear forensic odontologists apologize to him for his wrongful conviction. Six months later, he reveled in the news: the FSC recommended a moratorium on the use of bite-mark evidence in the criminal justice system. The recommendation wasn’t legally binding, noted the New York Times, “but is likely to carry great weight, in Texas and elsewhere.”

On Wednesday, August 3, Fabricant and Garcia will have a sit-down at 7 p.m. at BookPeople in Austin to talk about forensic science, the controversies, and his book, which came out in April to glowing reviews (“fierce and absorbing,” said the Washington Post). Fabricant has done numerous appearances across the country, but he says he’s especially looking forward to this one. “So much of what I wrote about was a shared experience with Lynn,” he said. “You can’t overstate how important she is to forensic science in Texas and nationally.” The two have gotten to know each other well through the half-dozen trips Fabricant has made to speak in front of the FSC. “We disagree about stuff,” he said. “She’s much more conservative than I am. It’s not like talking with my colleagues at the Innocence Project, who see things my way.” Still, he said, “Sometimes it’s frustrating when she won’t listen to me more.”

The two will talk about the FSC, which has become, in Fabricant’s words, “a national model for transparency and science-based decision-making—and an apolitical institution. It’s still an exemplar that stands head and shoulders above efforts in other states. The one in New York has been around for a long time but it’s been mired in politics for years.”

They’ll also talk about Chaney. Fabricant got to know him when Chaney was still behind bars—and even more once he was freed. Chaney died five and a half years later, in May 2021. “It’s hard for me not to feel the tragedy when I look at his life, what was done to him. At the same time, he maintained his faith in such a beautiful way, he kept his serenity in the face of the odds he was dealing with. He was never bitter.”

And they’ll probably talk about how, even though the FSC recommended a moratorium on the bite-mark evidence that sent Chaney to prison, it’s still admissible in court in all fifty states, including Texas. “I still get calls about it all the time,” said Fabricant. “I have three clients on death row, all who were put there by bite marks.” None of them are from Texas, although the next man set to be executed in Huntsville, Kosoul Chanthakoummane, was convicted of murder in part because of bite-mark testimony. His execution date is August 17.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Wrongful Convictions

- Austin