In 2008, when I got the chance to meet T. Boone Pickens for the first time—he had just turned eighty and was on a crusade to build wind-energy farms and get Americans into natural-gas-fueled cars—I was so stunned at his old-fashioned storytelling ability and his rustic sense of humor that I went straight home, called one of Pickens’s closest friends, and asked if the oilman was for real. “I think he was putting me on with some well-rehearsed act,” I said.

“Nope,” said Pickens’s friend.

“He acts like a character out of a movie,” I insisted. I looked at my notes. “Pickens literally said to me, ‘I guaran-damn-tee you that I’m going to make money on natural gas.’ No one says ‘guaran-damn-tee you’ except in the movies.”

“All real,” Pickens’s friend repeated. “One hundred percent Boone.”

A couple of weeks later, I traveled with Pickens on his Gulfstream jet to New York, where he was scheduled to give a round of press briefings about his new natural-gas energy plan. One night, he took about twenty people to dinner at some expensive Midtown restaurant. (The tab for the dinner alone must have amounted to two months of my salary.) I sat next to Becky Quick, a CNBC anchor. Someone asked Pickens an innocuous question—something about why, at his age, he was still embarking on new ventures—and he replied with a snort, “I don’t care about slowing down and taking vacations. I still want to run with the big dogs. And if you’re going to run with the big dogs, you’ve got to get out from underneath the porch!”

Quick saw me staring at Pickens, wide-eyed. “Seriously, he’s got to be putting us on,” I said.

“No, that’s just Boone,” she said. “That’s just the way he talks.”

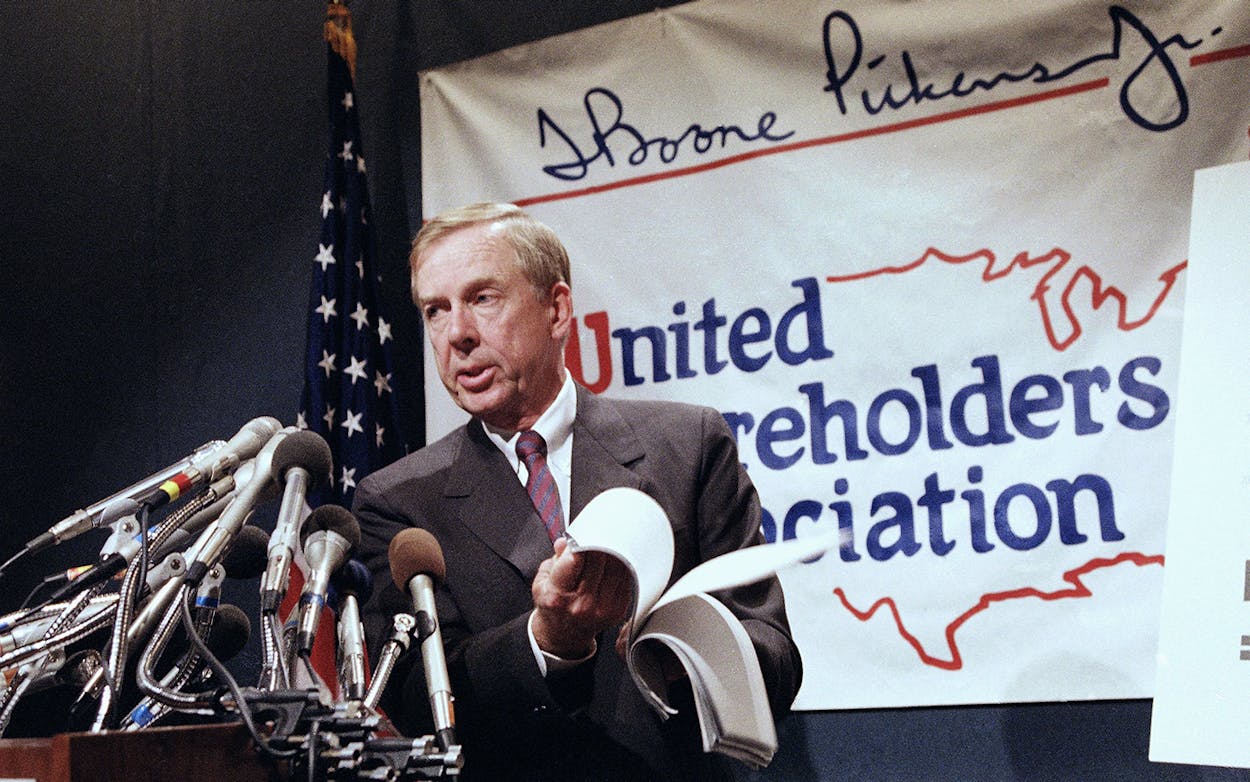

There’s one very simple reason why Pickens, who died Tuesday at the age of 91, has been profiled in our magazine more than any other oilman. (Joe Nocera wrote a famous cover story on him in October 1982, as Pickens staged hostile takeover raids of poorly performing publicly held oil companies. My cover story on him and his Pickens Plan, as he called his natural gas endeavor, ran 26 years later, in 2008.)

It wasn’t because Pickens was successful at extracting oil and gas from the earth. It wasn’t because he had a brilliant financial mind and a knack for figuring out whether the price of oil was about to go up or down. (Reporters loved calling him “the Oracle of Oil.”)

It was because Pickens just enjoyed the hell out of being a wheeler-dealer wildcatter. He loved making money, going broke, and getting rich again—over and over and over. And he especially loved talking about what he did and how he did it. In his plainspoken, hilariously vivid vernacular, he constantly spun tales about good times and bad. One of my favorite stories he told was about the geologist who fell off a ten-story building. When the geologist blew past the fifth floor, he thought to himself, “So far, so good.” Pickens said, “That’s the way to approach life. Never lose your optimism.”

Boone had so many good homespun lines that his friends began referring to them as Boone-isms. (Here’s one: “Show up early. Work hard. Stay late. Work eight hours and sleep eight hours, and make sure they are not the same eight hours.” Here’s another: “Show me a good loser, and I’ll show you a loser.”) One day, I was sitting in his office, listening to him to talk to Warren Buffett, whom he called Ol’ Warren. Buffett was apparently skeptical about the Pickens Plan. Pickens was undeterred. “The more people count me out, the more I count myself in,” he said, spouting off another one of his Boone-isms. He gave me a grin and held up the phone so that I could hear Buffett laughing.

Pickens loved talking to everyone, rich and not-so-rich. One afternoon, I went along with some other reporters to hear him talk to about three hundred residents of Pampa, a Panhandle town that was going to be the epicenter of one of his wind farms. I watched a young reporter from Wired tell Pickens that she had watched several episodes of Dallas, featuring none other than the character of J. R. Ewing, to prepare for her meeting him. Boone stared at her in bewilderment. “J. R. Ewing?” he asked.

“Yes,” the reporter replied.

“Well, to be honest with you, I was one of H. L. Hunt’s illegitimate children,” he said, his expression totally deadpan. “I came from his fourth family.”

Because he was a master of self-promotion, Boone got tons of free press. He no doubt got off easy with a lot of business journalists who could have been more skeptical about such things as his Pickens Plan. (It turned out that Ol’ Warren and other skeptics were right—natural gas was not as clean, efficient, and profitable as Pickens had advertised.) And I have to confess, I, too, was completely enamored of Pickens and his gift of countrified gab. I beamed with pride when he referred to me once as “Ol’ Skip.” My generation, I realized, was never going to produce another Pickens. The oilmen of my era are engineers, steeped in science. They are good on their laptops. They take statistical risks. They talk about 30 percent profit margins. They don’t take gambles the way Pickens did. Even though his natural-gas and wind-energy plans never worked, it was so damn fun to watch him try to pull them off.

And it was just as much fun to listen to him talk about his personal life. When I was interviewing him in 2008, he had just gotten married for the fourth time to a wealthy California woman named Madeleine Paulson, giving her a heart-shaped wedding ring the size of a small atomic bomb. “I knew Madeleine already had some big jewelry,” Pickens told me, “but I wasn’t going to be out-ringed.”

I last saw him in June at the funeral for Alan Peppard, the former society columnist for the Dallas Morning News who had grown close to Pickens and constantly wrote stories about him. Pickens had suffered a stroke and was clearly in failing health. But he seemed happy to be there, nodding at well-wishers. I delivered the eulogy for Peppard. I threw in a line about Pickens being there, and I added that everyone was happy to see him.

He slowly lifted his head and nodded. I beamed with pride.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- T Boone Pickens