This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was a family Ferrari,” said the witness. A wave of titters swept through the courtroom, but Don Dixon was not to be flustered. His round, middle-aged face framed by gray curls, the arch bad boy of the savings and loan industry was describing one of the company cars he drove while he controlled Vernon Savings and Loan. The $60,000 Ferrari, he intimated, was not an extravagance, because it was a four-seater with an automatic transmission—a family Ferrari.

For the spectators in the Santa Ana, California, bankruptcy court last June, the Ferrari had a different meaning. Most of the spectators were creditors trying to salvage something from the collapse of Dixon’s financial empire. Their chances weren’t very good: When federal regulators had taken over Vernon Savings three months earlier, a staggering 96 percent of the institution’s loans were delinquent. Extravagances like the Ferrari weren’t what broke Vernon Savings, but they did reflect the easy-money atmosphere that surrounded everything Vernon Savings did, from making speculative loans to underwriting Dixon’s high living.

The Ferrari and the bad loans have replaced stacked drilling rigs and idled pump jacks as leading symbols of Texas’ economic disaster. M. Danny Wall, the chairman of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, which regulates S&Ls, has called Vernon Savings the agency’s black hole and told the New York Times that “the damage done to Vernon by the management was irreparable.” In April the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation filed a $540 million suit against Dixon and six of Vernon’s former officers for “looting the assets of Vernon for their personal unjust enrichment.” The Federal Home Loan Bank Board closed Vernon in November and created a new institution, Montfort Savings Association, as part of a $1.3 billion bailout.

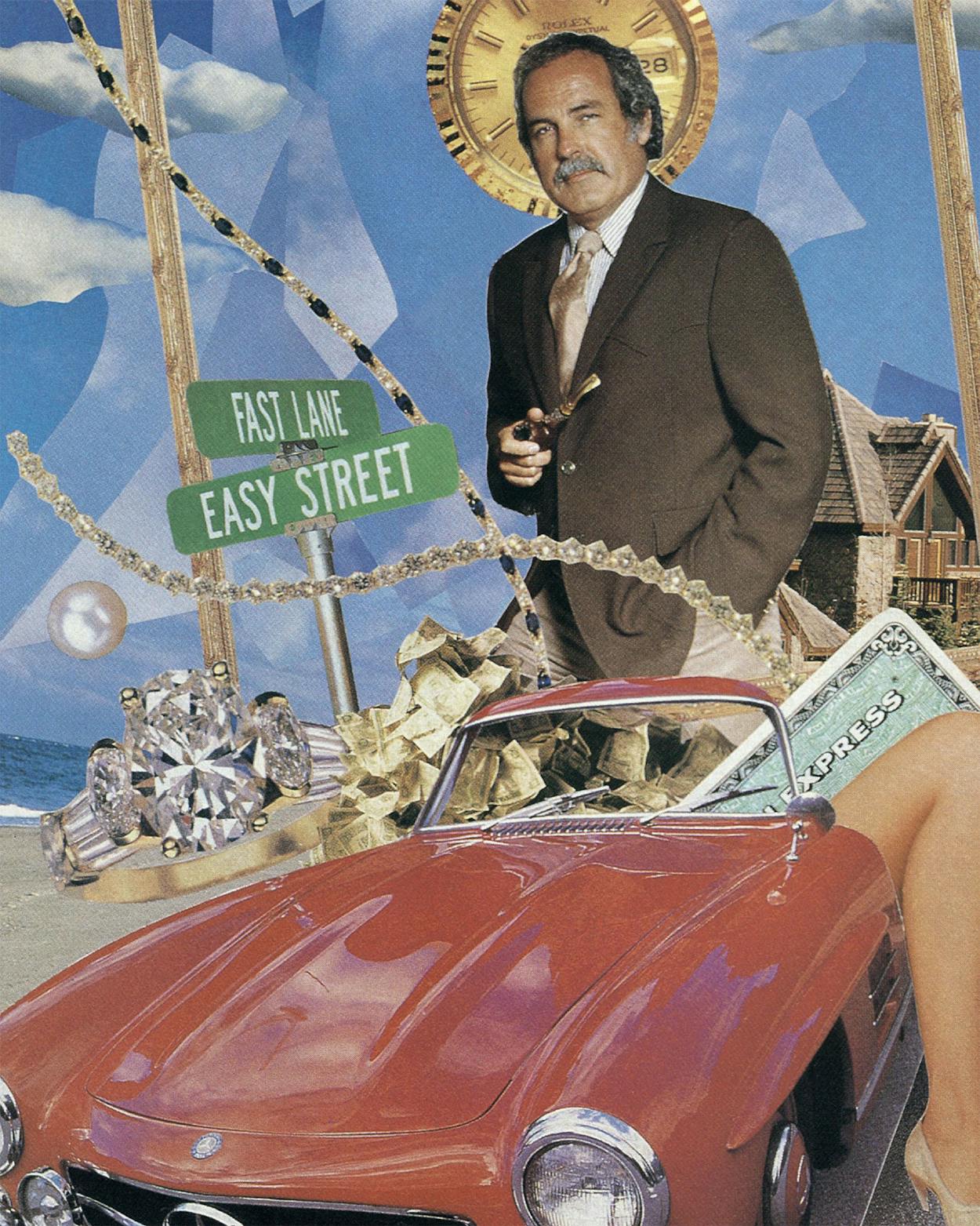

The family Ferrari was one luxury among many questioned by the creditors’ lawyers. Dixon’s valuables included custom-made shotguns at $25,000 apiece, his wife’s $75,000 diamond solitaire ring, his own collection of gold chains and jewelry, and $31,000 worth of French wines. What was on trial was not just Dixon’s business practices but also his lifestyle.

Dixon defended himself quietly but firmly, even venturing an occasional smirk while parrying hostile lawyers. He blamed the regulators and the press for his troubles and insisted that Vernon’s freewheeling way of operating was only business as usual in the newly deregulated savings and loan industry.

What makes that argument hard to buy is the trail of toys—the Ferrari and other cars, the houses, the airplanes, the yacht, the hunting lodge—that were Don Dixon’s to enjoy while he ran Vernon Savings. Those luxuries did not appear on Dixon’s list of personal assets in the bankruptcy proceedings because they were bought by Vernon Savings and are still on the company’s books. Dixon’s—and Vernon’s—prosperity was an illusion created by using other people’s money.

To read of Dixon’s wheeling and dealing is to be transported back in time to the giddy days of the boom, when every deal worked and nothing could go wrong. At least that’s how it must have seemed to people like Don Dixon. But then the deals stopped working, the money that belonged to other people went away, the illusion disappeared, and all that remained were the toys.

At the top of Dixon’s toy list were cars. Apparently cars have held a lifelong fascination for him, for although the list ended with a Ferrari, it began with a 1956 Thunderbird.

In his hometown of Vernon, about fifty miles west of Wichita Falls, some members of the class of 1956 still remember Don Dixon’s pea-green two-seater. The car was a graduation gift from his mother, and it clearly set Don apart from his classmates. The young Dixon already stood out because by combining the eleventh and twelfth grades he graduated a year early.

Don had inherited a large helping of ambition from his late father, W. D. Dixon, who had been both an editor of the Vernon Daily Record and a star on KVWC, a local radio station. W.D. was an aggressive personality in a relaxed town—a well-liked but never-say-die entrepreneur always looking for new ways to make money.

After graduating, Don enrolled at Rice Institute and studied architecture for two years. Then he transferred to UCLA, where he earned a business degree in 1960.

That same year, R. B. Tanner founded Vernon Savings and Loan. Vernon was a good place to start a thrift. The tallest building in town was a grain elevator, and the farmers and ranchers who borrowed money paid their debts promptly. Running a savings and loan at that time was generally a simple business. It meant husbanding the deposits of the townsfolk and lending money for home mortgages. The depositors assumed that the institution would be prudent enough in its lending that their deposits would not be threatened, that the regulators would be vigilant, and that federal insurance would kick in if disaster struck.

By 1981 Vernon Savings was one of the healthiest S&Ls in the state, with $82 million in assets and just $90,000 in delinquent loans. Tanner, who was considering retirement, had nurtured the institution to strength over the years by not taking chances, a lesson he had learned as a bank examiner in the Depression years of the late thirties.

According to Tanner, Vernon also had a reputation for being one of the cleanest S&Ls in the state. That was one of the reasons Don Dixon offered to buy it, Tanner said. The deal appealed to Tanner because Dixon was a Vernon native, and the $5.8 million Dixon was offering made it easy for the stockholders to like him. Dixon, who was building condominiums in Dallas through his Dondi Construction, had decided that acquiring an S&L made good business sense. Savings and loans were demanding part ownership in the real estate projects for which they were loaning money. Dixon wanted his own S&L so he could be, as he says, captain of his own ship.

Dixon’s rise to wealth began when he became the de facto captain of Vernon Savings in July 1981, purchasing the institution with other people’s money. Four fifths of the purchase price was put up by Tanner and other Vernon Savings stockholders, who were to be repaid with interest on a quarterly basis. The 20 percent down payment, Dixon says, was arranged with Mercantile Bank of Dallas by Louisiana businessman Herman Beebe, Sr., who in 1985 would be convicted of conspiring to defraud the Small Business Administration. Beebe’s company, Ami, Inc., guaranteed the Vernon stockholders’ note. Dixon says he was introduced to Beebe by Ben Barnes in 1976. Barnes and his business partner John Connally later would become significant borrowers from Vernon Savings.

On January 10, 1982, Dixon took over the ownership of Vernon. Technically the S&L belonged to Dondi Financial Corporation, whose stock was 70 percent owned by Dixon. Although Dixon himself was never an officer or a director of Vernon, he was a member of the loan committee, and former associates say it was clear that he ran the institution. The FSLIC lawsuit describes Dixon as Vernon’s “controlling person.”

Tanner and other standing members of the board remained after the takeover, but Tanner soon changed his mind about staying on. According to him, at his first board meeting Dixon announced Vernon’s purchase of a three-foot-tall bronze sculpture of a squatting Indian for $125,000. Irritated by the extravagance, Tanner resigned from the board.

Tanner’s resignation did not dissuade Dixon that art was a good investment, and the collection grew. By the time Vernon was taken over by federal regulators in 1987, it had about forty pieces of Western art valued on its books at $5.5 million. Much of Vernon’s artwork had been given away to borrowers and lenders of the institution.

The acquisition of expensive art was not the only way in which Dixon began to alter Vernon’s prudent operating style. Soon after he purchased Vernon, Dixon opened a branch office for the savings and loan in Dallas and began lending money. Most of the loans were not in the traditional area of home mortgages but rather in the much riskier and more glamorous area of commercial real estate. The corporate shell, which held all but the 9 percent of Vernon stock that was still in the hands of the original shareholders, began rapidly sprouting subsidiaries. Always described as generous, Dixon gave new managers part ownership in the subsidiaries, paid handsome salaries, and provided Mercedes sedans as company cars. Among the people Dixon hired were his wife, Dana, her sister, and his stepdaughter, who became officers of an interior-decorating company, Dondi Designs. The company eventually remodeled many of Vernon’s branch offices with the liberal use of western paintings and statuary.

Not long after the takeover of Vernon, in a transaction emblematic of the breakdown between Dixon’s investments and Vernon’s holdings, a property was moved from Dondi’s books to the S&L’s books. Dondi Farms, north of Dallas near McKinney, was listed on Vernon’s books as an investment, but Dixon’s stepson and family lived on the acreage and were paid as its caretakers.

Dixon had earned his spurs a decade earlier in the home construction business as a corporate executive of Raldon Homes, one of several companies to bear some form of Dixon’s name. Raldon, the creation of former SMU football player Raleigh Blakely and Don Dixon, was one of Dallas’ largest homebuilders in the early seventies. The company started out well, constructing homes in Dallas and Houston, but the 1974 recession knocked the market out from under all builders. Deeply in debt, Raldon was hurt more than others. By 1975 its lenders had forced Dixon and Blakely to divest themselves of Raldon Homes.

Despite the difficulties the company encountered, Dixon’s associates at Raldon praise him, describing him as honest, astute, and extremely ambitious. With his slight West Texas twang and low-key demeanor, Dixon was persuasive and personable.

Rick Ramsey, who knew Dixon at Raldon and later worked with him at Dondi and Vernon, saw little evidence at Raldon of the free spending and lavish lifestyle for which Dixon later became famous. At the time, of course, Raldon was in a financial crisis and under the watchful eyes of its bankers and creditors. But Ramsey says that by the time Dixon got to Vernon Savings, he was older and better versed in the ways of the world. Others who know Dixon well point out that when Dixon was at Raldon he was a borrower; when he was at Vernon he was a lender.

Whatever the reason, Don Dixon had changed. Having been the executive of a large corporation before he was 35, Dixon was more confident and more flamboyant than he had been at Raldon. There he had dressed conservatively; at Dondi gold chains and leather vests were his daily gear. For a marketing gimmick in 1981 Dixon’s staff at Dondi Construction printed up $3 bills with a caricature of their boss, complete with curly hair, moustache, and pipe, and the words “In Don We Trust” imprinted on one side. Dixon signed the fake currency as “Chairman of the Bored.” On the other side of the bill, ovals bore renditions of Dondi’s distinctive brickwork and red-tile roofs, two of the hallmarks of the hundreds of condominiums Dixon eventually built in the Dallas area.

With Dixon’s ownership of Vernon came a closer relationship with Herman Beebe, who had helped arrange the financing. Beebe would sweep into Dallas from his Shreveport, Louisiana, headquarters with an entourage, often traveling by limousine. In the early years Beebe was a financial mentor in the expansion of the Dondi empire, and Dixon became his pupil.

Beebe’s AMI, now defunct, was a web of corporate entities. Dondi became a similar maze. AMI owned insurance companies. Vernon Savings formed insurance subsidiaries of its own, eventually acquiring a Fort Worth insuror that had bought some of AMI’s business. Vernon Savings lent money to Beebe’s daughter and kept an account at a bank affiliated with Beebe, Bossier Bank and Trust. Before it failed the bank had two aircraft, one of them a jet. Vernon eventually had a fleet of five airplanes, two of them jets.

“Beebe had a style Dixon saw,” says Ramsey. That style was exemplified by the Beebe estate, constructed off what amounted to a private road outside Shreveport. There Beebe, his associates, and his relatives had a colony of Southern mansions set on sweeping lawns. Some bordered a serene pond, and adjoining the property was a stable where Beebe planned to raise horses.

Ramsey observed a gradual change in the teacher-pupil relationship by the early eighties: “Somewhere in that period they became almost competitors. Herman had this airplane, Don bought one bigger.”

Dixon could not have chosen a worse role model. Beebe has since been indicted twice for alleged financial misdeeds in Louisiana and convicted once. He has had connections with three failed banks and two failed savings and loans. A recent charge involving manipulation of bank accounts ended in a mistrial.

Dixon says he had no master plan for Vernon beyond the original idea that he could finance his real estate investments through his own thrift. “For the first year and a half,” Dixon says, “I didn’t even pay much attention to it. It was really an investment.”

If so, it was an investment with abundant opportunities for purchasing luxuries that were at Dixon’s disposal—luxuries that Vernon employees came to know as Dixon’s toys. Vernon records show that a year after its takeover the savings and loan began making some interesting investments. One was a $1 million residence on a cliff overlooking the Pacific in Solana Beach, California, where Dixon had set up an office for West Coast lending operations. Dixon and Dana visited the house often, leaving Dallas on Thursdays for long weekends by the ocean.

Vernon also began providing luxuries to its customers. In May 1983 two Vernon subsidiaries invested in a yacht in Florida, where the institution had also set up lending operations. The High Spirits was a $2.6 million sister ship to the U.S. presidential yacht Sequoia. One hundred twelve feet of teak and mahogany, the yacht was billed as a tax shelter for some of Vernon’s key borrowers. The institution lent the money for them to purchase shares of the boat, and Vernon bought two shares, or nearly a 20 percent interest. Dana Dixon presided over the redecoration of the craft.

Although the yacht was offered for charter, the costs to maintain its three-man crew were not recouped in revenues—Vernon Savings paid the operating expenses. In its $540 million lawsuit against Dixon and the six other Vernon officers, the FSLIC alleges that Vernon tried to remove the High Spirits loans from its books by overfunding a loan to a San Antonio–area shopping center by more than $2 million and using the excess to pay off the yacht.

The acquisition of Dixon’s toys continued. The trail of records on one property shows the convoluted path that marks the transactions of many of the state’s sickest savings and loans. Vernon records show that in April 1983 one of its subsidiaries spent $1.9 million for a “single-family residence” in Beaver Creek, Colorado. Vernon Savings originally loaned money to a third party for the purchase of the lot; it was briefly owned by a joint venture group, then in 1983 one Vernon subsidiary loaned another Vernon subsidiary the money to buy the dwelling. The “single-family” house, it turns out, is an eight-bedroom, seven-bath, two-and-a-half-story mini-hotel with two kitchens and two living rooms.

The Beaver Creek ski area has but 85 homes on its premises. Its select group of homeowners are carried to the lifts by limousine. Coffee and doughnuts are served en route, and at the end of the day the weary skiers are treated to a glass of sparkling wine on their ride home. Amenities like those make Beaver Creek a favorite of the well-to-do. Former president Gerald Ford lives up the road from the Vernon house.

If it seems peculiar that a savings and loan would own a house at a ski area, the fact that Vernon Savings was not the only institution with an investment at Beaver Creek indicates how far savings and loans were going with their “investments.” Several other Texas S&Ls that subsequently encountered difficulties maintained properties there.

If, as Dixon says, he didn’t pay much attention to Vernon for the first year and a half, it’s when he did start paying attention that things appear to really veer off course. Dixon began pursuing business investments that were further and further afield from the interests of Vernon Savings and Dixon’s previous business experience. In October 1983 Don and Dana Dixon jetted across Europe at the savings and loan’s expense. Dana wrote of the journey, “The trip was to be a ‘bit of a market study’ for the world-class restaurant to be opened in Dallas by Don Dixon in 1984 . . . very probably under the auspices of a famous French chef.”

On the way, indulging Dixon’s abiding interest in automobiles, the couple stopped in Pennsylvania for a classic-car show. Then it was off to France for what Dana later described as a “gastronomique–fantastique!” The Dixons flew to 7 three-star Michelin restaurants scattered over France. Flying on chartered aircraft they dined on roebuck in Alsace and sipped truffle soup in Lyons. Philippe Junot, the former husband of Princess Caroline of Monaco, orchestrated the arrangements as a paid consultant for Vernon.

Research for the opening of a restaurant was not the only opportunity the Dixons took for European travel. Dixon established Vernonvest, a subsidiary in Geneva set up to funnel money from European investors into Vernon ventures in the United States. Despite Dixon’s several trips to Europe between 1983 and 1986, on which he was accompanied by his wife and friends at an expense of $68,000 to Vernon Savings, Vernonvest never attracted much capital.

Vernon Savings was on a roll. Its assets nearly tripled to more than $440 million in 1983 as the savings and loan pumped expensive brokered money from investors into the hands of eager entrepreneurs. Most of those assets were in the form of loans on speculative real estate development.

Rick Ramsey says Dixon was an aggressive chief lending officer. “If a developer came in with a proposal that didn’t make sense, they would work on the deal to try to make it work,” Ramsey says.

Jack Brenner, a crusty ex-Marine with a construction background who was hired by Vernon to help iron out building problems, confirms that for many borrowers Vernon was the lender of last resort. Vernon’s customers, he says, paid as many as four percentage points more in interest because they couldn’t qualify for loans at conventional banks with lower rates.

Dixon says that a small real estate developer often “does his market research in his gut” and that prudent financial institutions must arrive at their own decisions on whether some projects make economic sense before lending on them. But many within Vernon don’t recall much prudence when it came to loan review. One officer who came on board in 1983 says there were no controls on loan making. Another describes the loan-approval process as being “like Radar O’Reilly taking something in for Colonel Potter to sign,” referring to the television comedy M*A*S*H.

The short-term incentives for Vernon’s officers to make the loans were strong. They received bonuses tied to the anticipated performance of the S&L. The more money the loan officers dealt out, the greater the institution’s potential profits and the greater their own bonuses. Dixon testified that he made more than $2 million in bonuses, issued through Dondi Financial Corporation, while he owned Vernon. Federal regulators say Dixon’s bonuses actually totaled more than $4.5 million, part of $22 million in bonuses paid through Dondi Financial.

An early signal that trouble might be on the way for Dixon’s empire came in 1984. That year, through an internal merger, Vernon Savings ascended to the pinnacle of the Dondi structure. Rick Ramsey was assigned to engineer the merger, and in the process of satisfying the strictures of federal regulators, he realized the S&L’s problems would soon be overwhelming. “We were still working on the last examination, trying to meet their standards for documentation and procedures,” says Ramsey, “but we were creating new loans and new problems out in front of us.” When he raised his concerns, Ramsey says, he was accused of not being a team player. In August 1984 Ramsey left Vernon.

The frantic pace did not wane. Vernon expanded its lending by nearly $460 million in 1984. Regulators say that with nearly every loan it made, the institution sowed the seeds of its destruction.

Again and again, Vernon’s purchases seemed to have less to do with business and more to do with executive pleasure. In May 1984 two Vernon subsidiaries became partners in Sugarloaf Hunting Associates, Limited, a hunting club near Crowell, about thirty miles southwest of Vernon. Hunting had been Dixon’s hobby since boyhood, when he shot quail with his father in West Texas. According to the incorporation papers, thirteen original partners invested $2.4 million in Sugarloaf. The partners built a Jacuzzi-equipped lodge big enough for a small national park overlooking a canyon at the site.

By the end of 1984 Vernon’s loan portfolio was nearing $1 billion. As its assets grew, so did the list of investments at Don Dixon’s disposal. In December the institution purchased a house on the beach in Del Mar, California, about thirty miles north of San Diego, for about $2 million. The Vernon board of directors was not consulted about the house purchase; indeed, the rapid pace of events at the S&L was passing the board by. Since Vernon’s deposits had begun coming in as $100,000 chunks at high interest through brokers in the East, the nine Vernon-area members, all in their sixties and seventies, seemed to be losing track of it all. The money had to be loaned out quickly and at a high interest rate for Vernon to succeed.

Dixon admits to living in the Del Mar house about 40 percent of the time during the next two years. The house was tended by a live-in housekeeper, who stocked it with groceries, liquor, and flowers. In its lawsuit against Dixon, the FSLIC alleges that a total of $561,874 was disbursed from a special account at Vernon for Dixon’s personal expenses there. Visitors to California say Vernon kept a small fleet of cars, including a Rolls-Royce, for transportation.

Entertainment in California was frequent and, some say, racy. Jack Brenner, after completing his stint as a Vernon apartment builder, was dispatched to California to manage construction finances there. “They were always having parties,” he says. “I went to one party, walked in, stayed about five minutes, and had to excuse myself. We left because the place was full of a maze of hookers.”

By 1985, in an unusual move even for the then deregulated savings and loan industry, Vernon invested in a Rolls-Royce–Ferrari dealership in trendy La Jolla, north of San Diego. The deal was justified on the grounds that it would help Vernon expand into the consumer-lending field. Appropriately, the dealership was named Symbolic Motors.

A dozen miles away, in pricey Rancho Santa Fe, Dana Dixon had opened a gallery, and Don Dixon was building a hillside mansion with eight garages and a two-story stable. A man-made waterfall set against boulders as big as small cars provided atmosphere.

Vernon’s books showed $1 billion in assets by the end of 1985, but there were a few clouds on the horizon. Dondi Residential Properties, one of the many subsidiaries Dixon had formed, was suffering from a surplus of condominiums. Dixon had grossly overestimated the market and had about seven hundred unsold condos on his hands. Internal projections indicated that the losses on the DRPI properties (or “Drippies,” as they were called inside the company) could run as high as $11 million. What to do?

Those inside the company say that a series of paper transactions was conceived to unload the Drippies onto a few of Vernon’s borrowers and book a profit for the institution. The Drippies were to be packaged with more-viable real estate deals later. The borrowers would never really have to take possession of the properties or make payments on them, and Vernon—at the end of the massive paper shell game, which federal regulators say involved 47 loans—would book a $25 million profit instead of an $11 million loss.

Ironically, an audience with Pope John Paul II turned out to be one of Dixon’s major blunders. In 1985 the Dixons made their most memorable European junket of all, a journey not just to the capitals of the continent but to the Vatican. In the process of building his S&L 1,000 percent in three years, Don Dixon had come to know the Catholic bishop of San Diego. The bishop, says Dixon, had asked for a donation to one of the church’s universities. Dixon responded by giving the school a block of stock in Dondi Financial.

In gratitude, according to Dixon, the bishop insisted that Dixon and his wife have an audience with the pope during the couple’s next trip to Europe. Thus on May 1, 1985, the Dixons found themselves chatting with the pontiff. Dana, whom Dixon describes as “having normal female tendencies” toward chatting, was speechless. Don did manage a conversation, and made the magnanimous gesture of giving the pope a painting valued at $40,000. He says, “I was very well aware of everything I said and that I was in the presence of someone very special.”

The trip was also special in many other ways. The Dixons and their clerical guests had traveled to Europe on a tri-jet Falcon 50, considered the Cadillac of corporate jets. The private plane itself would later be bad enough in the eyes of the regulators; that Dixon had used it to visit the pope and then stuck Vernon Savings with the bill would be worse. The trip was top drawer all the way, with lodging at the Grosvenor House in London, the Bristol Hotel in Paris, and the Hotel Ritz in Madrid, with stops at the Gucci and Bulgari boutiques in Rome. The party also stopped at Relais de Margaux in Bordeaux, a chateau that Dixon and some partners were renovating into a restaurant and hotel. The $17,319 in expenses was paid by Vernon Savings and Loan.

Dixon has said that he made two trips to Europe in 1985, one to entertain customers and borrowers and another to acquaint potential European borrowers with Vernon, but he and Dana broke away long enough to acquire furnishings for their new home. Court records show that they purchased $488,969 worth of antiques, financed by a note from a Dondi subsidiary, during a trip to London, where Dixon also added a 1951 Rolls-Royce to his classic-car collection.

If Dixon had a passion for prestigious cars, it was matched by a penchant for collecting famous people as friends.

Dixon numbered French wine connoisseur Alexis Lichine among his friends. Through Lichine, Dixon had purchased $31,000 worth of wine from France’s most prestigious chateaux. Ever generous with Vernon’s assets, Dixon took Lichine for a ride in the Falcon 50, an aircraft which had several famous passengers. Gerald Ford, Dixon’s neighbor at Beaver Creek, was a frequent flier. Vernon flight records indicate that Dixon gave the former president three lifts in the Falcon at a cost ranging from $5,752 to $13,119. Congressman Jack Kemp was a passenger on the jet, as were Speaker Jim Wright and Congressman Tony Coelho, the majority whip from California. Wright was later castigated by the press when word got out that he had pressured regulators to go lightly on Vernon and Dixon. Wright, who also accepted campaign donations from Dixon, denied that he had been influenced.

Within the company, the Falcon was regarded as Dixon’s personal jet, but the hundreds of thousands of dollars it cost for pilots, flight time, and upkeep were picked up by Vernon.

Back in Dallas, Dixon moved ahead with his plans to start a world-class restaurant adjacent to Vernon’s North Dallas headquarters. Called L’Archestrate, it was to be an American version of the restaurant of the same name in Paris and was to be presided over by Michelin three-star chef Alain Senderens, whom the Dixons had met on the gastronomique-fantastique trip. Vernon Savings advanced funds on the venture, but it never came to fruition.

Vernon’s fortunes rapidly turned sour in mid-1986. In June the Federal Home Loan Bank issued a cease and desist order against Vernon Savings. Such action by the federal regulator mandates strict controls on the way troubled financial institutions can conduct business. Regulators later said Vernon officers had ignored a previous supervisory agreement to curtail high-risk loans and brokered deposits. Soon after, in what is known among Vernon employees as the hangar party, Dixon called a meeting in the company’s facilities at the Addison airport. With his employees loosened up by hors d’oeuvres and an open bar, Dixon announced that he was stepping down from the savings and loan. The troops, who had been growing nervous with the presence of regulators in their midst, were relieved.

In July Symbolic Motors of La Jolla held an automobile auction at which Dixon sold eight antique cars, including his 1930 Duesenberg and his 1936 Mercedes. He received more than $1.7 million, or about 80 percent of the sale’s total proceeds, for them. The car dealership, however, lost more than $200,000 in expenses, and that bill went to Vernon.

Before Vernon’s sudden decline, its assets swelled to $1.3 billion, but by March 1987 the institution was declared insolvent. In the past, federal regulators would have shut Vernon down, liquidated its assets, and paid the losses from the FSLIC fund. But the fund was broke, in part because lending binges at other savings and loans had depleted it. Instead, the regulators ousted the directors and tacked the letters “F.S.A.” (for “Federal Savings Association”) onto the end of Vernon Savings and Loan’s name. Last November, after Congress voted new funds, the FSLIC finally transferred Vernon’s good loans to Montfort Savings, and Vernon Savings was no more.

As many as 87 savings and loans in Texas are operating with a negative net worth, according to the latest analysis by Sheshunoff and Company of Austin, the foremost analysts of financial institutions in the state. A savings and loan, however, regardless of its real financial condition, is insolvent only when federal regulators publicly declare it so. Thus Dixon, with the indignation of the speeder who gets a ticket while others rush by, claims selective enforcement.

Dixon’s Rancho Santa Fe house was never finished, and it is now in the possession of its lender, Sandia Savings of Albuquerque. His Chapter 11 proceedings have had the effect of freezing the 35 cases pending against him, including the one filed by federal regulators. But the judge in the bankruptcy, realizing that Dixon held a Texas driver’s license and voter’s registration, and that Dixon, until early in 1987, had lived in Texas most of the time, moved the case from California to Dallas.

How Dixon went from an income of nearly $1 million a year—with much of his living expenses paid by Vernon Savings—to bankruptcy is a progression that must be explained to his creditors. His one remaining asset, according to his court filings, is a part ownership in a BMW dealership in Newport Beach, California. He has already spent more than $1 million on legal help.

Many of Dixon’s creditors can’t spend that much trying to get their money back. R. B. Tanner, now 71, is one of several stockholders to whom Dixon still owes more than $2 million. Tanner’s health has declined as Vernon’s fortunes have unraveled, but he says he is “not going to let Vernon kill me.” The experience has not broken him financially, but it was an emotional blow. “It’s devastating to think that one fellow can do that to you,” says Tanner. “Take all that you’ve set aside for your retirement so that you can live peacefully after working forty-two years long and hard . . .”

Tanner is retired, but he still keeps an office adjoining his home in Denton. On the wall hangs a painting of the First State Bank of Dumas, the first institution Tanner inspected as a fledgling bank examiner in 1937. Those were difficult times, says the founder of Vernon Savings, but they were times when banking was executed mostly on trust, when “if a man said he’d pay you, he’d pay you.”

They were also times when people knew the difference between other people’s money and their own.

Byron Harris lives in Dallas. He is a reporter for WFAA-Tv and a free-lance writer.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads