On March 10, Governor Greg Abbott tweeted out a link to a Dallas Morning News article about the arrest of a Brownsville police officer named Valerie Rivas who had been charged with human smuggling. The story was a small news item, but the details were sensational. Rivas had been arrested two weeks earlier at Padre Island National Seashore after a Coast Guard helicopter making a nighttime surveillance flight had spotted her and another man hiding in the sand dunes. Rivas had told Border Patrol that she had come to the beach to search for her boyfriend, Alfredo Salazar, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, who had made arrangements to travel north. According to the initial news stories, Rivas had been planning to pick Salazar up in Victoria “after he had been smuggled into the U.S.”

The man hiding next to Rivas on the beach wasn’t her boyfriend but another undocumented Mexican immigrant, Jose Raul Perez. Perez had been traveling with Salazar and told Rivas that her boyfriend had gone up ahead with others in their group of seven. Rivas told authorities that she knew that Salazar was undocumented and, according to a Border Patrol agent’s sworn affidavit, Rivas “freely stated that when they heard the helicopter flying overhead, she attempted to hide from it, because she knew that it was illegal to transport illegal aliens and did not want to be apprehended doing so.”

The pattern of facts as laid out in the criminal complaint looked damning—possible evidence of something bigger, more organized, more nefarious. Was Salazar really her boyfriend? (The first time his name is mentioned in the criminal complaint, he is called her “boyfriend” in quotation marks.) Had Rivas really come to the beach just to look for Salazar, or was she there to help facilitate a larger smuggling operation? (Perez admitted that he’d paid “an unidentified man” $1,500 to get him across the border from Mexico into the United States.) After first appearing on the website of the Rio Grande Valley CBS affiliate KGBT, Rivas’s story got traction with conservative outlets like Breitbart, Fox News, and the U.K.’s Daily Mail. And once the governor saw the Dallas Morning News’s version, he decided to make a statement. “A law enforcement officer in Texas was caught illegally smuggling people into the United States,” Abbott wrote in his tweet. “This is Texas, not California. Expect tough sentence.”

A law enforcement officer in Texas was caught illegally smuggling people into the U.S. This is Texas, not California. Expect tough sentence. #txlege #tcot #PJNET @TexasGOP https://t.co/x5Avn42cFE

— Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) March 11, 2018

But last week, Rivas walked out of a federal courtroom in Corpus Christi, found not guilty of all charges against her. There were no press conferences and little fanfare. “The trial went as I expected, the evidence was fairly clear, and the jury only deliberated for about an hour,” said Micah Hatley, Rivas’s attorney.

During two days in the courtroom of Judge John D. Rainey, the jury hadn’t heard about Rivas’s role in a human smuggling ring, but rather the complications of maintaining a loving, long-term relationship in the geopolitical no-man’s-land of the Rio Grande Valley.

It was true that Salazar had been “smuggled into the U.S,” but the smuggling had happened two decades earlier when he crossed the Rio Grande as a boy with his parents. He had grown up in Brownsville and gone to public school. He and Rivas had started dating in the seventh grade and had been together ever since. They were both in their early twenties and had lived together for years.

Salazar knew that he didn’t have papers, and he’d spent nearly all of his life living between the Rio Grande and the internal Border Patrol checkpoints sixty miles north of the river. But, according to his lawyer, Roberto Vela, Salazar had “wanted to help out more than he was doing financially.” When Salazar heard that there was a shortage of construction labor in Victoria and Rockport and still plenty of Hurricane Harvey–related rebuilding work to do, he made arrangements to go.

Salazar was supposed to arrive in Victoria on Sunday, February 25, and contact Rivas to let him know that he’d made it. When she didn’t hear from him that night, she grew worried. When she tried reaching Salazar, her calls went straight to voicemail. His cell phone had run out of power.

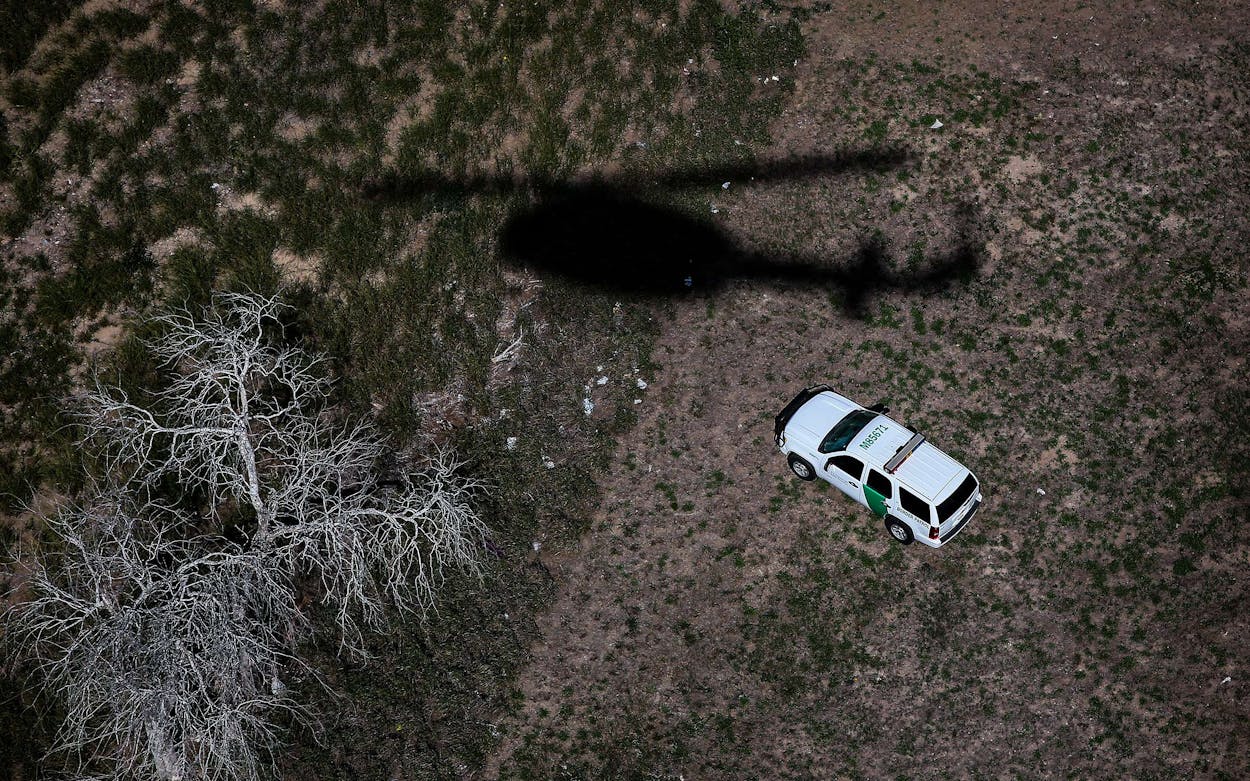

Rivas had learned that Salazar had been planning to walk north through Padre Island National Seashore and that the individuals who were supposed to pick him up had been arrested. So on the night of Monday, February 26, Rivas decided to drive out to the dunes to search for Salazar in the dark. She proceeded as far as she could in a Hyundai Tucson, then, when she became worried that her vehicle would get stuck in the sand, she took off on foot. She shined a flashlight to try to find Salazar or a trace of him. She blew a whistle in the hopes that he’d hear her and come out of hiding. Instead, she found Perez, the other undocumented immigrant. And then she heard the whir of the Coast Guard helicopter flying low.

Unbeknownst to Rivas, Border Patrol agents had found Salazar and another man walking along the beach that morning. They’d been traveling for days and had no water. In most circumstances, Salazar would have been deported quickly, but after Rivas’s arrest, the government held him as a material witness.

A grand jury ended up indicting Rivas on three charges: one related to conspiring to transport aliens, one related to concealing and harboring Perez at the scene of the arrest, and a third count that was more or less an indictment of Rivas’s daily life.

“Between on or about January 1, 2014 through or about February 20, 2018,” the count reads, “the defendant, Valerie Rivas, did knowingly and in reckless disregard of the fact that Alfonso[sic] Salazar-Hernandez was an alien who had come to, entered, and remained in the United States in violation of law, did knowingly and intentionally, conceal, harbor, [and] shield from detection…such alien.” In other words, Rivas, by cohabiting with her longtime boyfriend, was hiding him from the authorities.

But Rivas had made no secret of the fact that she was living with Salazar, even listing him as a reference when she went to work for the Brownsville Police Department. “She did just the opposite of trying to conceal him,” Hatley said. “The jury didn’t buy that count one bit.”

Now that Salazar is no longer needed as a material witness, he will almost certainly be deported. After Rivas’s arrest, the Brownsville Police Department placed her on administrative leave. She is now back at work, but her boyfriend is gone and likely won’t be able to return to the U.S. legally for at least three years.

“When I talked to the Border Patrol, one of their themes was that Ms. Rivas was a police officer, and she should have just called us up if she was going to go out there,” Hatley said. “I asked them, ‘What would you have done if you had found him?’ They said, ‘We would have deported him.’ I asked, ‘What would you have done with her if she said I’m a peace officer and I’m dating an alien?’ She’s put in an impossible situation, really. But that’s just the reality we live in.”

- More About:

- Border Patrol