About a century ago, in central Louisiana, in the town of Harrisonburg, the seat of Catahoula Parish, Arch and Mae Aplin opened a general mercantile store. The Aplins sold everything—dried goods and leather shoes, medicine and cotton shirts, cuts of beef and hammers and nails—and their store was successful, in large part because of its location.

Harrisonburg sits on the western bank of the Ouachita River, and back then the town was a hub for travelers. If you were heading east to Mississippi or west into the Louisiana Hill Country, you had to traverse the Ouachita, and the ferry that docked at the bottom of Main Street in Harrisonburg was one of the only ways to do that. The Aplins’ store stood on Main Street, just inland from the ferry. No one crossing the river in either direction could miss it.

But the Aplins didn’t just want customers of convenience. They took pride in their store. They called it Arch Aplin’s Biggest Little Store in Catahoula Parish, and they offered travelers products they couldn’t get anywhere else. The Aplins stocked turnip greens they’d harvested on their farm, and they sold syrup they’d made from their own sugarcane. Arch raised cattle and hogs, and he’d built a smokehouse on the family property to cure the meat he produced. It became famous throughout their corner of the Deep South.

“It was so good that the salesmen coming from Alexandria, Monroe, and Natchez, Mississippi, they’d put their order in for so many hams and so many pounds of sausage,” Arch and Mae’s son Arch Aplin Jr. remembered.

Arch Jr. was born in 1925, and he was more or less raised at the store. His mother nursed him in the back room when he was a baby. He worked there as a kid. And as a young man, when he’d returned home from the Pacific after World War II, he helped his parents run their business.

But Arch Jr. didn’t want that life. He went off to college, started work as a teacher and basketball coach, and soon moved with his wife, Lorita, to Lake Jackson, Texas, which had been built a decade earlier as a company town for Dow Chemical.

Arch Jr. had an entrepreneurial streak, like his parents, and he started to build houses. He was good at it, and soon he left teaching to work full-time constructing churches, post offices, apartments, and entire subdivisions.

In 1958 Lorita gave birth to Arch Aplin III. Like his father, Arch III was raised in his family’s businesses. On trips to visit his grandparents in Harrisonburg, Arch III would eagerly throw himself into pumping gas and the work of the general store, while forever pestering Arch and Mae to let him man the cash register. (They told him he was too young.) In Lake Jackson, he absorbed the home-building trade, spending his teenage summers working on his father’s construction crews. When Arch III went off to Texas A&M, he majored in construction sciences. He wanted to follow in his father’s path, but he wanted to do it bigger. “I thought I would build skyscrapers,” Arch III said.

But in 1982, two years after graduating from college, Arch III got another idea. He knew that there was an unused property next to a four-way stop sign on the border between Lake Jackson and the town of Clute. He thought he could talk its owner, a well-to-do Houston banker named A. G. McNeese Jr., into selling. He did. His plans for the property seemed modest: at 23 years old, Arch III decided he would not build a skyscraper but a kind of general mercantile store of his own.

Arch III wanted to make his store just a little special. Sure, he would offer the same beef jerky and chips and soda as everyone else, but he installed brass ceiling fans and wrapped the upper parts of the walls in rough cedar. His store would be a little more inviting too, a roomy 3,000 square feet instead of the industry-average 2,400.

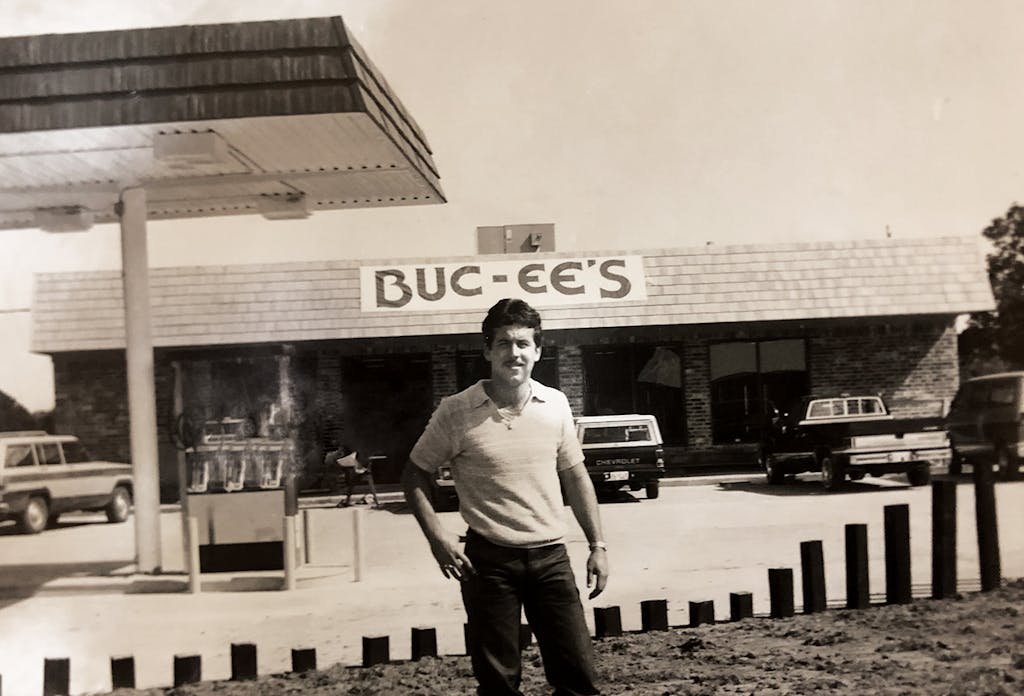

On July 28, 1982, Arch III opened his store at 899 Oyster Creek Drive, right where it crossed Old Angleton Road. Early on, he decided he’d need a good name and a good logo, something he could build on. The logo wasn’t ready by the time the store opened, but he’d already commissioned it. It would be a cartoon riff on his nickname since childhood, Beaver.

The name of the store, too, drew inspiration from his life. When Beaver was a kid, one of his father’s colleagues called him Bucky Beaver, after a cartoon character featured in Ipana toothpaste ads. Beaver had also had a beloved hunting dog, a Lab that he named Buck. The nearby high school in Brazoswood had the Buccaneers as their mascot. It all added up.

“I think you’ll see it’s the nicest, prettiest store around. It’s very sharp looking,” Aplin told the Brazosport Facts on the store’s opening day. “I believe everyone who comes in will be in awe over the way it looks.” He made clear his ambitions were bigger than that one location. “If this one goes like we hope it will, you never can tell, we might have a chain of Buc-ee’s.”

If he dreamed that one day his creation might become a Texas icon, a temple of roadside convenience and everything’s-bigger abundance, and that it would even reach a point, in 2019, when it would outgrow Texas, he certainly didn’t share the thought at the time. He was just a kid from Lake Jackson following in his family’s footsteps.

On a rainy afternoon in earlyDecember last year, I met Beaver Aplin inside the Buc-ee’s location in Bastrop. He’d agreed to walk me around the store only if I promised I wouldn’t make him sound like he was bragging. Aplin, now sixty, is only five foot seven and slight, but inside a store full of casually dressed highway travelers and peppy uniformed employees, he cut an outsized figure. He wore a wide-brimmed hat and a dark windowpane blazer, and he kept his gray hair and beard a little long and shaggy, like Jeff Bridges or Kris Kristofferson. Tucked under both legs of Aplin’s jeans were big red-and-yellow Buc-ee’s beaver logos sewn onto the shins of his cowboy boots. The tip of his right index finger was wrapped in a Buc-ee’s bandage.

The Bastrop Buc-ee’s opened in 2012, and it has more or less the same relationship to the first Buc-ee’s store that a Boeing 747 has to the biplane the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk. The store occupies 56,000 square feet and has aisles wide enough to drive a golf cart through. It has 71 toilets and urinals and a team of custodians whose entire job is to clean the bathrooms 24 hours a day. It has 96 gas pumps under two canopies selling Buc-ee’s-branded fuel. There are 655 parking spaces that fan out from the store on three sides, and they’re extra roomy, 10 feet by 20 feet instead of the standard 9 by 18, so as to better accommodate Texans’ trucks.

It might all seem “a touch overkill,” Aplin allowed. “But I don’t ever want to be over capacity. We like to make it spacious, give everybody their own space and their own shopping experience. It’s one of the reasons it gets so big, because if you try to enhance the space everywhere, it just grows, and then the next thing you know . . .” He trailed off.

As we walked the floor, it became clear just how many times “the next thing you know” has happened at Buc-ee’s. We stared up at a towering wall of gummy candies, taffies, candy corn, and cherry sours. (“The selection is almost overwhelming, which is good,” Aplin said.) He led me to a corner of the store stocked with cooking gear—Buc-ee’s spatulas, Lodge cast-iron pans, open-fire cookbooks, a $1,000 offset smoker. (“I just think it’s cool. I think it’s Texas. It’s chuck wagon. It’s cooking the cowboy way.”) He wended his way past the shelves of hot sauce and mayhaw jelly, Buc-ee’s barbecue spice rub and Buc-ee’s raw wildflower honey. (“This comes from a young man in Lake Jackson. He’s quite a beekeeper.”) He marveled at the refrigerated deli counter with hunks of jerky (thirteen varieties), dried sausage links, and spicy venison sticks. He stopped in front of an easy-to-miss refrigerator stocked with an assortment of prepared dishes, among them crawfish fettuccine, bacon-wrapped pork tenderloin, and chicken cordon bleu.

By the time Aplin made it to the barbecue station, a circular island Buc-ee’s calls the Texas Round Up, he couldn’t resist a sample. Two employees were methodically slicing brisket and placing portions onto hamburger buns, but Aplin decided to grab a bag of freshly made potato chips instead. They were still warm from the fryer, crisp and browned with just a little chewiness on the inside—perfection. “We’re slicing the potatoes, cooking them right here,” Aplin said.

At that point, aromas became our guide. “They’re roasting the nuts right here, right now,” Aplin told me, pointing to a nearby station. “It’s fresh, it’s wonderful, they bag it.”

The woman roasting the nuts smiled at Aplin. “You sell a million times more when you’re roasting than when you’re not,” she said. Aplin played it cool. She didn’t seem to recognize him as the direct beneficiary of all those extra sales.

The nut roaster also made the store’s fudge, and Aplin asked for a couple of samples. She handed them over with a smile. She said she’d made 23 pans that morning.

“I love my job,” she said.

“I love that you love what you do,” Aplin replied.

The interaction wasn’t staged, but it was by design. Buc-ee’s pays its employees well above market rate; cashiers start at $14 per hour in most locations and get three weeks’ paid vacation and a 401(k) plan, in an industry where it’s common for cashiers to make minimum wage, about half as much. Aplin expects smiles and attentive service in exchange. There’s no sitting on the job and no using cellphones. Like cast members in an elaborate theatrical production, employees also must adhere to certain wardrobe and grooming standards. They are not allowed to display visible tattoos or body piercings. Men are prohibited from having long hair; nobody can have unnaturally colored hair. There are no open-toed shoes, no torn or faded clothing.

Buc-ee’s employees who buy into this don’t just love their jobs, they tend to become evangelists. And as Aplin walked through the store, he met up with one of them, Mallory Bevers, the Bastrop store’s 26-year-old gift manager. Back in high school, Bevers said, everyone she knew had to have a Buc-ee’s T-shirt. They needed to stop at Buc-ee’s on trips. Buc-ee’s was cool. She still pinched herself that she was now working there. “It’s just so crazy looking back on that, and now I have the Buc-ee’s name tag,” she said.

Bevers is responsible for the store’s most eclectic department. In the gift section, you can find everything from a slinky leopard-print kimono to twelve-inch stuffed beavers to designer totes to a vast grab-bag category of all things Texana: dueling UT and A&M gear, cowhide rugs and cowhide koozies. “Anything that has the Duke, Willie, or Nolan Ryan on it is a big seller here,” Bevers said.

Bevers had known that Buc-ee’s was big before she went to work there, but she’d come to appreciate just how widespread the store’s cult following had become.

“We’ll have people come from out of state and say, ‘I was told that we couldn’t go to Texas without stopping here.’ ”

The Buc-ee’s store in Bastrop may be staggeringly oversized in just about every way, but in the Buc-ee’s empire, it’s not particularly special, just one of fourteen enormous stores and not even close to the biggest. (The chain’s New Braunfels location, at 68,000 square feet, has been recognized as the “world’s largest c-store” by the National Association of Convenience Stores.) Still, Buc-ee’s has a tiny footprint in the national convenience-store landscape. The industry leader, 7-Eleven, has more than 9,000 locations nationwide. Circle K, running a close second, has nearly 8,500. Buc-ee’s has 34 stores total.

But Buc-ee’s has a reputation far greater than its store count. It has become the rare brand—like Apple and Costco—that inspires loyalty that goes well beyond rational consumer calculations. People love Buc-ee’s, and they like to talk about how much they love Buc-ee’s. When the company opened its New Braunfels location, in 2012, ten thousand people came to shop on the first day. When the company opened its Fort Worth location, in 2016, fans lined up to wait for the 6 a.m. grand opening like Black Friday deal-seekers trying to nab a cheap 4K TV. When the comedian and UFC commentator Joe Rogan stopped at a Buc-ee’s, in 2015, he became an instant convert, posting a string of ecstatic Instagram videos showing the towering wall of candies and endless rows of gas pumps. “I’m not making any of this up!” Rogan shouted. Texas chefs have expressed their devotion to various Buc-ee’s-branded snacks. (The restaurateur Ford Fry, who owns La Lucha, in Houston, called Buc-ee’s “the gold standard for road-trip junk food.”) Texas-themed social media routinely post Buc-ee’s content. As the Texas Humor Twitter account wrote in 2016: “If you bypass gas stations because you’re waiting to stop at Buc-ee’s instead, you’re definitely from Texas.”

Quips like those make it sound as if Buc-ee’s has always been there, that it’s been a fixture of the state for decades, a tradition passed down through generations and immortalized in the prose of Larry McMurtry, like Dairy Queen trips on summer nights. In truth, the store’s cult following is a recent phenomenon.

When Aplin opened the first Buc-ee’s in 1982, he may have had ambitions for more stores, but he grew his chain slowly. He didn’t open the second Buc-ee’s until 1985, and while it was bigger (six thousand square feet) and more innovative than the first (it had an on-site kitchen that churned out sandwiches, breakfast tacos, and doughnuts), it was still a far cry from the stores to come. Aplin didn’t open the second location alone; by then he had partnered with another area convenience-store owner, Don Wasek.

For the first three years of their partnership, Aplin and Wasek shared a desk, and the close quarters created a mind-meld. “After three years working off the same desk, you get to know a person,” Wasek once said.

The two men brought complementary skill sets. Wasek, whose father had been a Lone Star beer distributor, was fluent in supply chains and retail operations. He also preferred to stay in the background. Aplin was the resident Buc-ee’s dreamer and not only the brand’s public face but its personification, a Gulf Coast good ol’ boy named Beaver who had come to the convenience-store business honestly. “He’d be comfortable gigging frogs in the creek in the country somewhere,” said Lou Congelio, a Houston adman who worked with Buc-ee’s in the mid-2000s. “It takes you by surprise that he has the business acumen.”

During its first two decades, Buc-ee’s became a regional powerhouse, opening twenty stores, most of them in Brazoria County. The expansion was relatively conservative and deliberate. Aplin and Wasek financed their projects with bank loans instead of raising capital by giving up equity to outside investors. (Today they still own the company outright, as 50-50 shareholders.) But the partners were also constantly looking for the next big thing. In 1989 they opened Buc-ee’s Beach Store, in Freeport, marking the first time the company sold clothing and fishing gear. In 1991 they entered the live-music business, starting a Lake Jackson icehouse called Uncle Buck’s. Their regular stores became ever spiffier too, with Aplin enlisting the well-known convenience-store designer Jim Mitchell to help make Buc-ee’s both more welcoming and more profitable.

“I try to accomplish a free-form effect that I believe brings in more sales by encouraging the customer to meander through the store,” Aplin told Convenience Store Merchandiser in 1986.

Still, these were subtle tweaks. If Joe Rogan had stopped by a Brazoria County Buc-ee’s location in the eighties or nineties, he wouldn’t have felt the need to say, “I’m not making any of this up!” But in 2003, when Aplin and Wasek opened a store in Luling, they were ready to take their business to another level. Luling was the first Buc-ee’s location that looked like what most Texans now think of as a Buc-ee’s location. It was off an interstate and geared toward long-distance travelers. Eighteen-wheelers were banned in an effort to differentiate the store from truck stops and attract families. It offered barbecue sandwiches and soon added Buc-ee’s-branded T-shirts and a caramel-covered corn-puff snack the company called Beaver Nuggets.

And Luling kept expanding. In 2006 Aplin and Wasek nearly doubled the store’s square footage, to 17,000. Then, in 2009, they nearly doubled it again. In the same year, Buc-ee’s opened similarly sized stores in Madisonville and Wharton. These three locations weren’t just convenience stores; they were, in industry parlance, travel centers, and they created what has become the Buc-ee’s model. They were situated on major roads that connected major population centers. They were far enough away from big cities that they could serve as logical stopping points on multi-hour car trips. They weren’t just pit stops. They were highway oases.

The travel centers made Buc-ee’s famous. In 2006, three years after the launch of the Luling store, Aplin and Wasek hired the Houston advertising firm Stan & Lou to help them rethink their highway marketing approach. “The mission on my part was to let people know about the brand,” Congelio, the principal creative, told me. “I pictured myself traveling across Texas, two screaming kids in the back. The idea was to put a smile on people’s faces. It would be a safe space to go and a fun place to go.”

Congelio helped Aplin and Wasek refine the firm’s voice, and he proposed a series of billboard ideas to sell the stores’ offerings with a chuckle. One read, “Only 262 Miles to Buc-ee’s. You Can Hold It.” Another said, “If It Harms Beavers We’re Against It.” Still another: “Top Two Reasons to Stop at Buc-ee’s: #1 and #2.”

Congelio’s focus on bodily functions wasn’t by accident. Aplin and Wasek “really wanted to stress the clean rest-rooms,” he remembers. Because, well, a comfortable place to relieve oneself is a universal need, one not well met by existing options. And the early plaudits for Buc-ee’s tended to focus on that. In 2009, when the company was profiled on ABC’s World News Tonight, the segment concluded with the words “this is a business built purely on porcelain.” In 2012 the New Braunfels store was awarded the honor of America’s Best Restroom in a survey by the corporate-restroom-supply firm Cintas. But the Buc-ee’s reputation for excellence has expanded. In 2016 Bon Appétit named Buc-ee’s “America’s Best Rest Stop” in honor of its food. In 2018 Gas Buddy, a fuel-price app, gave Buc-ee’s the distinction of the country’s best gas station. The Katy Buc-ee’s, which opened in late 2017, has been certified by the Guinness Book of World Records as having the world’s longest car wash. (It has 25 separate rolling brushes and takes five minutes to pass through.)

“They’ve hit a really sweet spot in a couple ways,” said Matt McCutchin, a longtime advertising creative director who now teaches at the University of Texas’s Stan Richards School of Advertising and Public Relations. “Every time you stop, you’re going to have an overwhelming experience—the best bathrooms, the most gas pumps, the best coffee and tea and brisket. Everything is sort of to the nth level, but they also have found this perfect symbol, this eager little beaver, that connects with people on an emotional level. It’s magical, almost.”

McCutchin told me he’d seen this connection happen personally. His eight-year-old son collects Buc-ee’s T-shirts, and on road trips the boy asks specifically to stop there. “There’s so much merchandise involved. Kids get a keepsake stuffed animal, they take a picture with the bronze beaver statue in the front. It’s more of a Disney experience than a gas station experience.”

Offering a family-friendly, clean-restroom, Texas-proud retail experience has proved to be very good business for Aplin and Wasek. Two years before the Luling store opened, the chain’s sales totaled $63 million, according to a court filing. By 2006, when the Luling store expanded from 10,000 to 17,000 square feet, total sales had more than tripled to $202 million. In 2015 the company took in $959 million. Since then, Aplin and Wasek have opened up four more 50,000-square-foot stores.

One morning in early January, I visited Aplin’s office in Lake Jackson. It looked like a Hollywood set for a movie about a Texas CEO. There were floor-to-ceiling windows looking out over a grove of oak trees, gauzy watercolors of fishermen casting into the surf, and trophies from Aplin’s hunting and fishing adventures—a big speckled trout caught while wade-fishing off Port O’Connor; a sling of ducks inside a wooden case; photographs of impressive bucks nabbed at Corazón Ranch, a South Texas property that Aplin and Wasek share. Then there was a different kind of trophy, from Bank of America, commemorating a $15 million construction loan. There was a framed and signed photograph of Aplin and then-Governor George W. Bush and a scale model of the Cessna Citation Jet that Aplin and Wasek co-own. (Aplin is a multi-engine, instrument-rated pilot and can fly second-in-command on some light jets.) On Aplin’s desk sat a copy of Leading Matters, a management book by the Silicon Valley grandee John L. Hennessy, a former Stanford University president and chairman of Google’s parent company, Alphabet. On a wall, Aplin had hung the $52,800 check he wrote to A. G. McNeese Jr. as a payment on the property for the first Buc-ee’s.

Aplin and Wasek no longer work at the same desk, of course, or even in the same building. While Aplin works from Lake Jackson, Wasek now has an office on the nineteenth floor of the Google tower in downtown Austin. The two men have distinct roles. Wasek runs operations—everything from HR to negotiating with oil refineries. Aplin handles “conception to completion”—where the stores will be, what they’ll look like, and how they’re going to get built.

In one corner of his office, Aplin had hung up a handy guide to this part of the business. It was a road map of the United States, and he’d pressed dozens of thumbtacks into it. In Texas, the markers clearly showed the existing Buc-ee’s locations, as well as under-construction stores in Royse City, Ennis, and Melissa. Each represented years of work for Aplin: finding or piecing together twelve- to fifteen-acre plots of land; pushing cities to create better infrastructure, from water lines to overpasses; and lobbying for incentives to compensate the company for its investment and the promise of hundreds of new jobs and gobs of tax revenue. (Buc-ee’s has not always been welcomed with open arms. In Denton, residents mounted a campaign to stop Buc-ee’s from coming, but the company prevailed after Aplin offered $2 million for road improvements.)

As Buc-ee’s has become an ever bigger part of Texas, Aplin has gotten more active in the politics of the state. He has donated $325,000 to Governor Greg Abbott since 2014 and has also contributed generously to the campaigns of Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and House Speaker Dennis Bonnen. (After Patrick announced Aplin’s and Wasek’s endorsements in the 2014 primaries, a short-lived #BoycottBucees hashtag trended on Twitter.) In the early days of Buc-ee’s, Aplin served on the local school board. Last November, Abbott named him to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission.

But Aplin’s ambitions are now outgrowing the state. That map in the corner of his office included thumbtacks outside Texas—lots of them, stretching over to North Carolina and down to Florida. I told Aplin it looked like he was planning an invasion.

“It does kind of look like an invasion, doesn’t it?” he said.

Over the past several years, the company has begun buying land throughout the Southeast, and on January 21 it opened a new, 53,000-square-foot location off I-10 in Robertsdale, Alabama, its first store outside Texas. The initial signs were promising. Just as they had in Fort Worth, Buc-ee’s fans lined up outside the store in the hours before it opened, eager to be the first to grab a bag of Beaver Nuggets or use the much-ballyhooed bathrooms. But Robertsdale is just a beachhead. Three Florida projects—in Daytona Beach, St. Augustine, and Fort Myers—will break ground soon.

The most audacious plans on the map were still in the conceptual stage, Aplin said. Atlanta was encircled by no fewer than six thumbtacks pressed into locations where Aplin is still looking for the right deal. The plan is simple: If you are driving from Atlanta to Nashville, you will pass a Buc-ee’s. If you are driving from Atlanta to Charlotte, you will pass a Buc-ee’s. If you are driving from Atlanta to Birmingham, you will pass a Buc-ee’s. At that point, Aplin hopes, Buc-ee’s will become just as much a way of life for Georgians as it is for Texans.

Aplin believes this is possible, even as Buc-ee’s has built its reputation in part by piggybacking on the brand of Texas itself. The store has parlayed the hoariest Texas clichés into a playground of excess. But Aplin thinks these cultural signifiers are not really so exclusively Texan. “I theorize that the people traveling in Texas are very similar to the people traveling in Florida or Alabama,” he told me. “They’re looking for basically the same thing.” Instead of UT and A&M duking it out in the gift section, he’ll have Auburn and Alabama or FSU and Florida.

But consider a store between Atlanta and Charlotte. Those cities may be the same number of miles away from each other as Houston and Dallas, but culturally they’re farther apart. They have different college rivalries and regional cuisines and histories. Will a peach cobbler in Georgia give North Carolinian travelers the same feeling of home that a slice of brisket gives Texans in New Braunfels? Sure, many Texas-born brands have gone national—Southwest Airlines, Whole Foods, Tito’s Handmade Vodka—but not every big Texas brand has translated to differing tastes in other states.

In the eighties, Whataburger embarked on an aggressive expansion strategy outside Texas. The company added menu items like popcorn shrimp salads and steak sandwiches that it hoped would diversify its appeal. Instead, the company failed to catch on in locations including Las Vegas and Memphis, where residents greeted the arrival of new Whataburgers with little enthusiasm. “We got spread too thin,” one Whataburger executive told Texas Monthly in 2000. “People didn’t know who we were. We didn’t have that Texas heritage and Texas tradition to play off of.”

Whataburger eventually righted itself, partially by retrenching, but the lesson remains. Sometimes a business can expand beyond its appeal. Sometimes the magic that makes people identify emotionally with a profit-seeking enterprise can evaporate. Maybe the good people of Alabama and Florida will thrill to Buc-ee’s just as much as Texans do. Or maybe they’ll look at the Disney World of convenience stores and just see an oversized convenience store.

“Buc-ee’s kind of has that cachet of being a rare place, so if they expand too big, too quickly, they could lose some of that charm,” said Greg Lindenberg, an editor at convenience-store trade publication CSP Daily News. “I remember when you couldn’t get Coors beer and Krispy Kreme doughnuts [in a lot of places], and once you could get those things, you realized, ‘They’re okay, but I’m not sure what all the fuss was about.’ ”

Aplin is dedicated to making sure Buc-ee’s is worth the fuss. No matter how big the stores have gotten, he sees the formula as basically unchanged. Since 1982, he has emphasized the importance of keeping the facilities spotless, offering good customer service, and making sure the shelves are always full. His motto was and remains “Clean, Friendly, and In Stock.”

But Aplin is also a ruthless competitor. Take the fuel prices at Buc-ee’s, which are among the lowest in the nation. The company can afford to undercut rivals not only because its locations have so many pumps but because it makes its real money on jerky and stuffed beavers. Less than two weeks after the Alabama store opening, a nearby travel center sued Buc-ee’s for “unfair and predatory” gas pricing (which Buc-ee’s denies).

Aplin aggressively defends his company’s turf, too. Over the past six years, Buc-ee’s has pursued trademark-infringement lawsuits against a series of smaller convenience stores—Chicks, in Bryan; B&B Grocery, in Uvalde; Irv’s Field Store, in Waller—all of which Buc-ee’s believed had ripped off part of its brand. Last year, a Buc-ee’s lawsuit against an Atascosa travel center called Choke Canyon made it all the way to trial in federal court, where Buc-ee’s accused its rival of stealing key parts of the Buc-ee’s brand, among them a “friendly smiling cartoon animal similarly oriented within a circle and wearing a hat pointed to the right” (in Choke Canyon’s case, the animal was an alligator) and even Beaver Nuggets themselves, which Choke Canyon passed off as “Golden Caramel Corn Nuggets.” (The jury decided in favor of Buc-ee’s.)

Aplin knows that the risk of someone else copying his business increases the more Buc-ee’s grows. But he hopes to stay ahead of copycats by trying to go one step further, one step bigger. Next to the map in Aplin’s office, there’s a drafting table. Aplin isn’t a trained architect, but he knows how to draw (“just enough to be dangerous,” he told me), and he pens new construction layouts, new placements for products, new paths to keep customers meandering through the store with smiles and open wallets. No feature is too sacred for tinkering. Earlier this year, the company began installing a new technology called Tooshlights above each restroom stall; they turn green if the door is unlocked and red if it’s locked, which not only makes finding an empty stall quicker and less awkward for customers but gives Buc-ee’s a never-ending stream of data about how people use the facilities—the better to optimize them with.

When I arrived at the Lake Jackson office that January morning, Aplin told me I’d come just in time for a taste test. Last year, in anticipation of the company’s next big phase of expansion, Aplin had hired his first culinary director, a career chef named Jim Mills, to focus on “the artistry of creation rather than the execution day to day.” On a table in the office, Mills had arranged pairs of similar products. One item in the pair was a product Buc-ee’s currently served. The second was what Mills hoped was an improved version that would replace it.

Buc-ee’s bacon was up first. Mills thought it wasn’t flavorful enough and could be a little limp. He’d sourced new bacon that he hoped would be smokier and crunchier. Mills’s deputy, Randy Pauly, placed two bacon-and-egg croissants in front of Aplin. Aplin examined them both, twisting the breakfast sandwiches in his hand. He nibbled the first, then sampled the second, then turned his attention back to the first. Mills, Pauly, and Buc-ee’s pastry chef Susan Molzan stared at their boss. Aplin was poker-faced. His lips didn’t curl into a satisfied smile. His eyes didn’t wince in disgust. He seemed lost in his own thoughts. Then he looked up.

“I find this crumbled bacon superior. It’s crunchier, but it also distributes better over the whole sandwich. Your every bite has bacon, whereas with the strip, maybe not.”

“It’s also a more flavorful product,” Mills replied. “It’s naturally smoked, just has more pop in the mouth, I think.”

Aplin kept going. He judged new recipes for red and green salsas (“I don’t know what I want. It already has bam”). He gamed out the reintroduction of a discontinued jalapeño-cheddar sausage biscuit (“I’d like the follow-up opinion of the numbers, what really happened”). He tasted and approved an overhaul of the entire chicken-salad line. He considered a new concept for more travel-friendly salad shakers. Most vexingly, he puzzled over yogurt parfait.

Mills and his team had identified a problem. The current packaging included two distinct parts: a granola-filled dome lid and a yogurt-filled cup. Customers were supposed to pry the dome lid open, then mix the granola into the cup. But the cup was filled to the top with yogurt. There was “no headspace to put the granola in,” Mills explained.

The chef had a solution. Instead of a dome lid, he wanted to use a flat-topped lid with a plastic compartment that would sit inside the top of the cup. That way, when customers lifted the granola-filled lid off of the yogurt-filled cup, there would be some empty space in which to put the granola. But if you did that, the cup also looked three-quarters full, like Buc-ee’s was skimping on its portion sizes.

“This looks cool,” Mills said of the current product, “but you don’t know the trouble that lurks within, whereas this one is more user-friendly.”

Aplin nodded. “The lid will have a big impact on you,” he said.

They went back and forth. Aplin needed to balance utility with pizzazz. Ultimately he wanted more information. He wanted to try out additional lids and packaging options. Maybe there was a solution that could be as attractive as it was practical. “Let’s play with the lids. Bring them here. Let me put them on. Let me experience it,” Aplin said. Then he moved on to dessert.

Aplin was stuffed, but it was banana pudding, and banana pudding was a fan favorite at Buc-ee’s. He wanted to see what Mills and Molzan had dreamed up.

“We had dang good banana pudding, but this is a nice tweak, which is what we want to do. If big improvements are to be had, then we probably didn’t have the right product, the right recipe, the right mixture to begin with,” Aplin said.

“A lot of what we do is incremental,” Mills said.

“Incremental adds up,” Aplin finished.

An hour later, Aplin and I were alone in his office. He was between meetings, and it was a rare moment of calm. His day was packed. His month was packed. His life was packed. Aplin likes to cast himself as an aw-shucks shopkeep, but creating Buc-ee’s had clearly required monumental ambition and a few sharp elbows. I wondered if Aplin would cop to that. I pointed out to him that he could have stopped at the first Buc-ee’s location and made a halfway-decent living. He could have stopped with a handful of stores around Brazoria County and been wealthy enough to own a hunting ranch. Now he had a map in his office plotting a corporate expansion that looked like Sherman’s March. There was a pretty big difference between his current life and how he’d started 37 years ago.

“I guess there is a little difference in that,” he said. “You know, I built the first store within a half mile of where I lived. It’s still there. It’s a nice store.”

I tried again.

“I always pushed the envelope,” he said. “The standard-size store was twenty-four-hundred square feet, and my first store was three thousand square feet. My second store was bigger than almost anyone had seen in the area. I assume it’s in my blood, because, as I say, my grandpa had a store.”

As his grandpa had, Aplin just wanted his store to be a little better than the others. He just wanted to take care of customers. Expand the square footage a little, add some gas pumps, clean the restrooms a few extra times a day, make sure the granola fit just so in the yogurt parfait, and maybe—just maybe—a gas station convenience store at 899 Oyster Creek Drive, on the border of Lake Jackson and Clute, would grow and grow and grow until, the next thing you knew, it had fanned out and conquered America’s highways.

This article originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.