This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Tom Philpott’s apartment looks like the apartment of any sixties-spawned leftist graduate student: the living room has wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, El Salvador and Bobby Kennedy posters, a frayed and fading floral print sofa, two large stacks of records leaning against one wall (Frank Sinatra and Carlos Santana outwardmost), a filing cabinet doubling as an end table. The dining room holds a metal and fake-wood-veneer dinette set. The bedroom is stark, dominated by a venerable four-poster on one wall. But there, just above the headboard at about waist height, is the one anomalous touch: a neat round hole in the white plasterboard. On the adjacent wall, slightly higher, is another hole, made, like the first, by a .38-caliber bullet.

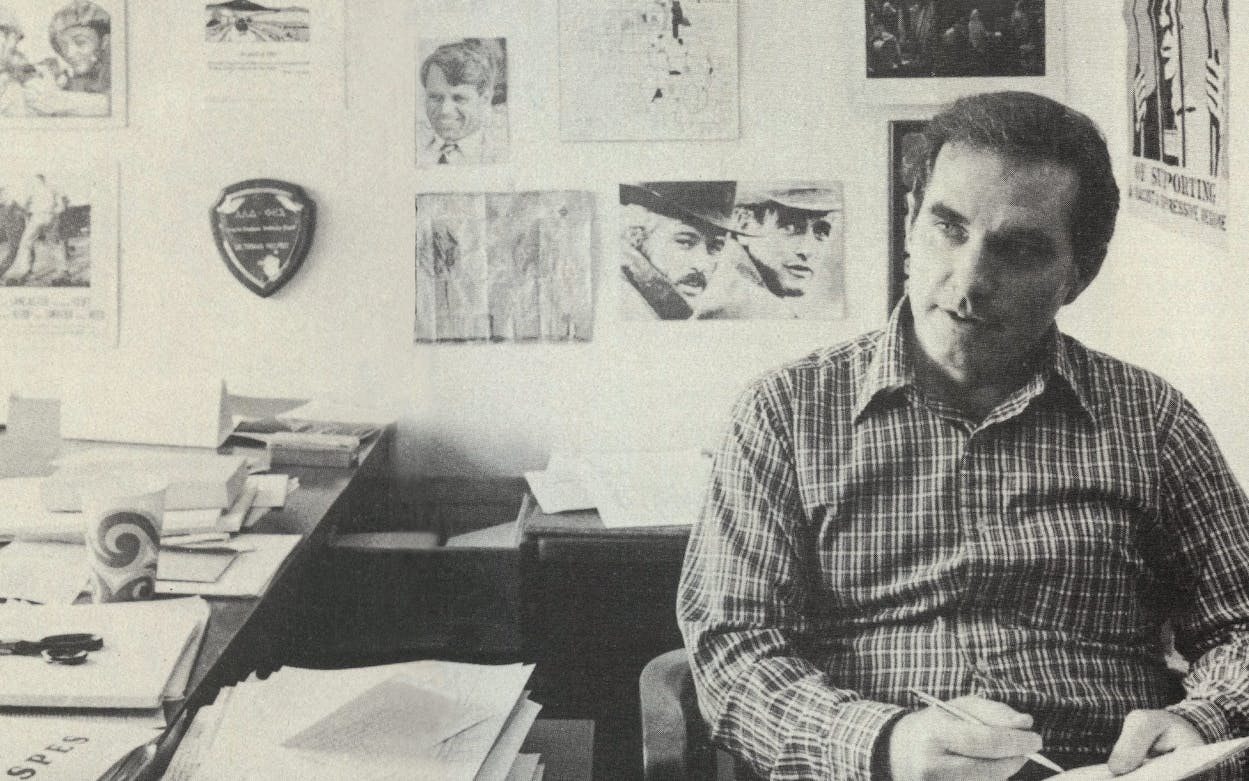

At first glance, Philpott himself might pass for a graduate student, rather than the associate professor of history that he is. Up close, though, he looks every bit of his forty years. A liberal sprinkling of gray peppers his sandy hair, a gentle paunch mars the compactness of his five-nine frame, and a wariness tightens the skin around his wide, ingenuous eyes. But perhaps the most striking thing about him is a gesture: from time to time, unconsciously, it seems, Philpott kneads fretfully on his upper left arm and rotates it gingerly to flex his shoulder. Across the back of that shoulder runs a livid three- or four-inch scar, made by the same slug that now rests in the wall above his bed. The wound and the bullet hole date from last October 27, when, Philpott says, two intruders broke into the Austin apartment and shot him with the Sterling Arms .38-caliber automatic pistol they took from a shelf beside the bed.

Popular young college professors, even notoriously outspoken ones like Tom Philpott, aren’t expected to get shot; the attack created a storm on the University of Texas campus. Philpott told the campus newspaper, the Daily Texan, that the shooting had come as no surprise to him. In fact, he had been expecting something of the sort for some time. He said he had made mortal enemies by investigating pederasty and organized child prostitution, and he interpreted the attack as an attempt to discredit his work by creating the impression that he had committed suicide. However, the Austin police let it be known that they found his story farfetched. Within days, the case of State Representative Mike Martin—accused of having had himself shot as a publicity gimmick—was being invoked as a parallel. The police stopped investigating altogether when Philpott, like Martin, refused to take a polygraph test. He said the results would not be valid because he is a diagnosed manic-depressive, and manic-depressives do not test reliably, but that didn’t mollify the police.

If the shooting made Philpott a genuine celebrity, his face and name were hardly unknown at UT or in Austin before October 27. As one of the most vocal left-leaning scholars at one of the nation’s leading universities, Philpott has been visible in almost every city- and campus-wide controversy of the past thirteen years, from integration of the public schools to curbs on Austin’s growth, from city, state, and national politics to the selection of university presidents and regents, and from the tenuring of controversial professors to U.S. foreign policy in Viet Nam, Iran, and El Salvador. His intense, highly opinionated lectures on the inequities of American society have drawn huge classes, a devoted band of followers, and more than a little criticism from faculty and students. (In March Philpott was named among both the twenty best and the twenty worst professors in a student poll conducted by the UT campus magazine.)

Every university has its Tom Philpott; there’s always at least one professor who turns up at the center of every controversy, who seems to make his living as the administration’s quasi-official gadfly and whipping boy. Each attracts his own little bands of followers and critics. Philpott is of a type: the radical professor. He is something quite different from the professor who happens to privately hold radical political views. He is radical first, professor second. Tom Philpott’s fondest dream is to be remembered among the great American social crusaders, to join a pantheon that includes Jane Addams, Clarence Darrow, Jacob Riis, Frederick Douglass, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King. Many people at UT scoff at the very idea; that, too, is the usual lot of the radical professor. In only one way does Philpott depart from the common folkways of radical professordom. He got shot.

Philpott’s apartment houses curiosities other than bullet holes. One sits in a frame on the bookshelf: a yellowing certificate of naturalization issued by the U.S. government in 1913 to one Thomas Francis Lee, then aged 25 and listed as a subject of Great Britain. In point of fact, Lee, the maternal grandfather and namesake of Thomas Lee Philpott, was an Irishman. At fifteen, he had run away from an overbearing stepfather to follow his older brother and sister to Chicago. Thomas Lee’s people were of the merchant class, but Tom Philpott’s maternal grandmother and his father were descended from shanty Irish, peasants who had fled the Potato Famine of the 1840s. Philpott’s father, an accounting clerk, died in 1943, just one year after Tom, the second of his two sons, was born. His widow got a job as executive secretary to the president of the Rock Island Railroad and moved herself and her two boys into her parents’ modest apartment on Chicago’s South Side, next to the Illinois Central tracks. Tom slept on a daybed in the dining room.

Tom was essentially raised by his grandparents in that respectable lower-middle-class neighborhood, near both the opulent Gold Coast along Lake Michigan and the tenements of Steeltown. As a smaller-than-average child he learned to take his knocks. He was, he says, always getting into fights—and always losing. Tom recalls his grandfather fondly as a complex, inarticulate man whose conscience was frequently at war with his emotions. Thomas Lee disliked blacks, for example, but he regarded that dislike as a sin, and acting on it as an even greater sin. Tom remembers his grandmother simply as “the nicest human being I’ve ever known.” The old couple raised the boy with an easy hand and he adored them in return, although he envied his friends for having both a mother and a father. It was his grandpa who first impressed upon him the importance of learning. “Get your education, Thomas,” the old man told him. “It’s the one thing they can’t take away from you.”

“At the time I didn’t know who ‘they’ were,” Philpott says, “but of course ‘they’ were the British. Grandpa thought just like an Irishman.”

Flash-forward: It’s a wintry afternoon in early 1982. Philpott is giving a lecture on Ireland as part of the UT student union’s International Cultures Week. “I was born in the U.S., but I’m an Irishman,” he tells the 25 or so listeners drawn up in a circle on sofas and chairs. “The Irish have a history terrible among the peoples of the world,” he says solemnly. “Irish symbols reek of loss. And yet the Irish carry a great burden of guilt, because in fighting British desecrations they have committed atrocities of their own. Only an Irishman could have said, ‘It is not those who can inflict the most but those that can suffer the most who will conquer.’

“The Irish boast of little in their culture, but they do have one telling conceit: their capacity for love. Irish blood gives the warmth that keeps the human race from freezing over. Only an Irishman could also have said: ‘The strength of a man is in his sympathies.’ That statement is as alien as is conceivable to American culture. Americans think the Irish and Irish Americans are barbaric—not because of their violence but because of their feeling.”

Like the South Side, Tom’s Catholic elementary school brought together rich and poor. (“I was in grammar school,” he recalls, “when it suddenly hit me that some kids lived in houses.”) Also like his neighborhood, his classes were lily-white. The only time he entered the city’s Black Belt was when he traversed it on the way to Comiskey Park to see the White Sox play.

But when he reached high school age, Tom began to commute to the same parish school his father had attended. It lay five miles from home on the opposite side of the Black Belt, so now he rode a bus through the ghetto twice each day. It was the late fifties and the nation was just beginning to feel the reverberations of Brown v. Board of Education and the first civil rights demonstrations. In 1955 a black Chicago youth named Emmett Till went to visit relatives in Mississippi. He was found drowned in chains after he supposedly whistled at a white woman. At about the same time, Tom Philpott bought and read a book called Stride Toward Freedom, by Martin Luther King, Jr.—though at first he worried that the author, being named after Martin Luther, might be an evil man.

Tom had seen blacks ejected from his church and from Rainbow Beach on Lake Michigan, where he swam, and it disturbed him. When a parish priest exhorted students at a football pep rally to “kill the monkeys” from the black school across town, Philpott threw a penny at his feet and was made to stay after school every day through the end of the year. Undeterred, he joined sympathy demonstrations against national merchants whose lunch counters Southern blacks were struggling to integrate and took part in a wade-in to integrate the beach. (“Goddammit, Thomas,” his grandfather later complained after a trip to the beach, “it’s a fright. It’s like going to Africa.”)

While Tom was in high school his mother remarried and moved to Evanston. But he stayed behind with his grandparents in order not to lose his friends, his job at the local newsstand, and most of all, his new girlfriend. Her name was Anne, and she was beautiful, Irish, Catholic, and confined to a wheelchair. Neither of them seriously dated anyone else. “There was a certain charm to believing in the sanctity of marriage and virginity,” Philpott says. “I went all the way through college on sublimated sex drive.”

Spring semester, 1982: Students file into UT’s Burdine Auditorium for History 315L, “America Since 1865,” special section for foreign students. Standing alone on the broad stage of the 540-seat hall, flanked by two enormous movie screens, Philpott looks smaller than ever, peculiarly vulnerable. The term has just begun and he’s giving the class, composed of 120 or so foreign students and roughly the same number of Americans, an overview lecture listed on the syllabus under the heading “The Promised Land—The American Creed.”

But first things first. “I’m not big on dates,” Philpott assures the class. “I’m not going to make you memorize a lot of numbers. But there is one date I think you should know.” Two hundred forty notebooks rustle expectantly. “January 21, 1942.” Two hundred forty pens go into action. “Exactly forty years ago today is when I date the beginning of modern history. . . . That’s the day I was born.” Pens stop in midsentence; the class laughs.

Then the lights dim. A photo of the Statue of Liberty appears on the right-hand screen. “The fundamental question of American history,” Philpott begins, “is whether or not this nation has lived up to its rhetorical creed, to the concept it was founded on: that America’s unique abundance would create a society of unlimited opportunity, a society with no barriers to class mobility and no poverty.” (If any of the students doubt the accuracy of that highly debatable formulation, they keep quiet.)

The Statue of Liberty vanishes, a Pluck and Luck comic book giving the success story of a fictional office boy takes her place. On the opposite screen a gaggle of grimy child miners stare hollowly into the camera. More slides: on the right a nineteenth-century illustration of the ladder of success; on the left a nineteenth-century photo of children working in a textile mill. “In 1932 Franklin Roosevelt said the aim of government should be to take care of the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid. In this class we’re going to take a look at those forgotten men.”

Still more slides: William Vanderbilt’s block-long New York mansion; a design for “model“ tenements so cramped that almost eight hundred families could be squeezed into a single block. “Poverty. Disease. Vice. Violence,” Philpott spits the words out like insults. “Crime. Disorder. Wretchedness. These things weren’t supposed to happen in America.” A measured silence. “I’m an American, I still believe in the dream. I just don’t think it’s been applied very successfully. I urge you to take the risk of being critical. I won’t teach any other way. I’d rather go back to driving a bus or selling newspapers as I did when I was a young street kid rising to fame and fortune . . . such as I enjoy here before you today.”

Tom Philpott arrived at Chicago’s Loyola University in 1959 planning to study English literature and left it four years later with a degree in history and a commitment to teaching. In the interim he continued to, as he says, “do a little moving and shaking” in the realm of protest politics. He led a drive to protect the job of a professor who had angered the school’s Catholic hierarchy by documenting the German church’s acquiescence to the Nazis; he helped organize a boycott of a segregated swimming pool near the campus. The boycott fizzled, Philpott recalls wryly, when one of his friends in the Loyola administration pointed out “where the greater good lay”—that is, that the owners of the building that housed the segregated pool were important benefactors of the university.

The budding radical also joined the ROTC, however. He planned to marry Anne, and he thought that a man with a handicapped wife had better go into the Army as an officer if he was obliged to go at all. Their wedding took place in 1963, as soon as both had graduated. They moved into one of Chicago’s few integrated apartment buildings, where they were neighbors to the radical comedian Dick Gregory. Tom enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Chicago, supplementing his fellowship by driving buses and working at the newsstand and the university gym. Meanwhile, Anne cared for the two sons and one daughter she bore within the marriage’s first four years.

Philpott thrived on the political ferment of the sixties. By mid-decade the focus of the civil rights movement had shifted northward, and Dr. King had chosen Chicago as the crucible of the fair housing fight. When King arrived in 1966 to stage fair housing marches, Philpott marched. When blacks and whites organized a rent strike in an apartment complex, Philpott traipsed up and down stairs and hallways distributing literature, proud to demonstrate that a graduate student could be content to do the legwork and leave the planning to the common people. He also worked with Saul Alinsky in the Woodlawn Organization to draft a model cities program to counter one written by Mayor Richard Daley’s staff. (Daley’s plan wound up being challenged in court, so Hizzoner got President Lyndon Johnson to have the guidelines governing such programs changed.)

Philpott’s mentor at the University of Chicago, Richard Wade, indoctrinated him into Democratic party politics—so deeply that in 1968 he helped organize the Indiana towns of Gary and Whiting for Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign. The day after Kennedy died, Philpott went to meet Wade at the candidate’s Chicago headquarters. “Richard was the merriest person I’ve ever known,” Philpott says, “but when I got there he was crying. He took my hand and patted it and then he kissed it. I said, This is it, I quit.’ Then he grinned. ‘You can’t, Tom,’ he said. ‘No one is allowed to quit until he turns thirty.’ ” Philpott falls silent, then he says softly, “I had written Bobby in 1967, saying, ‘You’ve got to run, no matter what it does to you.’ ”

America Since 1865” revisited: Philpott begins class by pointing out an article in the Daily Texan about the Reagan administration’s decision to send emergency military aid to El Salvador despite congressional concern over the Salvadoran junta’s civil rights record. “If you’re going to defend that,” he snaps at the class, “I, as a professor and as a citizen of this country and the world, challenge you to at least know how it is being done. . . . Hmmm. I don’t have the slightest idea what’s going on behind those masks that are your faces.”

With a shrug, he picks up the historical thread of the previous lecture. “The Puritans were very radical in some ways,” he says. “They believed that each individual bore responsibility for the whole community. If society was corrupt, and filthy, and vicious, the individual had a responsibility to set himself in opposition to it.”

It’s time for the slides—Lincoln on the left, Martin Luther King on the right. Under their stern gaze Philpott draws a large circle on the chalkboard. The circle, he says, is the limit of popular opinion within which every politician must stay. Outside lies the territory of another sort of leader, who seeks to expand the limits of that public tolerance. “Those men are called reformers after they’re dead,” he says. “While they’re alive they’re called agitators, subversives, terrorists. Reformers can afford to be bold—up to a point. Both of these men”—he gestures at the screens—“were assassinated.”

Shifting gears, he reviews the presidential careers of Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, complete with slides, winding up with a photo of a tearful Bobby Kennedy standing beside his brother’s coffin. “Robert Kennedy was the most loved and hated man in America,” Philpott tells the class. “He voiced the unspoken needs of those who had no advocates —blacks, other minorities, the poor. And he was winning, he was pushing out the limits of American opinion. The most intense political activity in American history was trying to get him elected president. But in 1968 he was shot down. He was cut out of America’s life, and since then no one has even tried to fill his place.” (Any number of politicians might quibble with that one, but they’re not present to object.)

“War. Inequality. Poverty. Injustice. Those are hot subjects. They’re avoided by the politicians, the press, the preachers, because they’re dangerous. Do professors raise them?” The class laughs nervously. “Is it prudent for a professor to go into a classroom and talk about inequality and injustice? It is not prudent.”

In 1969, having finished all of his course work but not his dissertation, Philpott accepted UT’s offer of an instructorship. Anne, at least, was not impressed with their adopted state. “The drive was awful,” she remembers. “It was August, we had no air conditioning, and everything from Oklahoma on looked completely barren. I hated Austin for about a year.” They could find no racially mixed neighborhood like the one they had left, so they chose the next-best thing: an all-white area of modest houses in Northeast Austin that looked like a good bet to become mixed as East Austin’s black population grew.

With his family settled if not content, Philpott embarked on his nerve-racking first semester by throwing up in the men’s room before each class. In 1970 he began team-teaching a course called “The American Experience.” It quickly became one of the most talked-about and sought-after classes on campus, particularly among freshmen and sophomores hungry to fulfill subject requirements, for whom its three hours of history, three hours of government, and three hours of English credits were an unequaled bonanza. At its peak, the course drew more than 800 students per semester; by the time Philpott quit teaching it in 1981, over 12,000 young minds had been exposed to his multimedia vision of American history. The Philpott legend took hold and flourished, one of its cornerstones being that he always cried in class at least once a semester. (Philpott admits that he may occasionally get misty-eyed over the plight of the poor and oppressed, but it exasperates him that every reporter seizes on this one detail as the most salient fact of his career.)

Wading through the voluminous sheaves of evaluations filled out by students who took “The American Experience,” “The American City,” or “America Since 1865,” one discerns a running thread of disaffection: “biased,” “poorly organized,” “repetitive,” “too subjective,” “too emotional,” “likely to cause a riot someday,” and even the grudging “You may be a bleeding heart, but you play the part well.” But most of the comments read like cover blurbs from a smash best-seller: “a great course,” “the highlight of my college career,” “one of the most meaningful things I’ve ever done,” “unforgettable,” “a good teacher and a good man,” “a beautiful man,” “Philpott, people like you are all the hope this country has got.”

With his career at UT established, Philpott dabbled assiduously in local politics. He testified before the city council on school desegregation; he worked on the Austin Tomorrow Goals Assembly, which wrote the city’s master plan. He helped found a group called the Northeast Austin Democrats and thrice was a delegate to the state Democratic convention. Anne and Tom organized a precinct for George McGovern in 1972 and campaigned for liberal state representative Gonzalo Barrientos in 1972 and 1974. A 1974 letter to the Daily Texan from Philpott and Texas Observer publisher Ronnie Dugger is a classically Philpottian piece of political rhetoric: “Gonzalo is un hombre de sentimientos, a man of feelings. He deserves to win . . .”

Philpott also kept busy in his own neighborhood, which, as he had foreseen, over the years became first racially mixed and then almost exclusively black. When the Philpotts welcomed rather than resisted the change, white neighbors stoned and egged their house and car and harassed their three children. Even after the racial balance shifted, the tension took years to abate; it came to a head when a bicycle stolen from one of the Philpott children turned up at the home of a black family; Philpott got his jaw broken and was threatened with a gun when he went to retrieve the bike.

One upshot of all this activity was that Philpott never quite got around to completing the dissertation that stood between him and his doctorate. In 1972 UT gave him notice that he would have to leave in a year. With that incentive he finished the project. (It was published in 1978 by the Oxford University Press as The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterioration and Middle-Class Reform, Chicago 1880–1930, and it drew favorable notices from such eminences as Harvard education professor Nathan Glazer, who called it “a fine and sobering book.”) UT rescinded its edict and in 1974 welcomed Philpott to the fold for good by granting him tenure and promoting him to associate professor.

It was a move the administration soon had reason to rue. Philpott’s running confrontation with the university began in 1975 when acting president Lorene Rogers invited Kennedy-Johnson brain truster McGeorge Bundy, one architect of the Viet Nam War, to speak at UT’s graduation ceremonies. A few students heckled Bundy; they were ejected from the proceedings by campus police; Philpott and one other professor walked out in protest. That summer when Rogers formulated the next year’s salaries, Philpott found that he had gotten a $900 raise rather than the $2000 his department had recommended. After several weeks of accusations and counteraccusations, Philpott and six other politically active professors whose recommended raises had been cut—including the man who had left commencement with Philpott—filed suit against the university for “pursuing a course of conduct designed . . . to curtail free expression at the University of Texas at Austin.”

The suit took four and a half years to come to trial, but in March 1980 federal district judge Jack Roberts ruled against all the professors. (Three appealed; the Fifth Circuit Court overturned Roberts’s ruling in favor of one.) In Philpott’s case, Rogers said she hadn’t even known that any teachers walked out of commencement. She said she had overruled the department’s salary recommendation because Philpott’s career was shaky, he had been granted tenure only one year after receiving his Ph.D., and he had not at that time published a book. But in a handwritten memo to his american Civil Liberties Union lawyer, Philpott outlined a darker scenario:

Commencement is the single biggest annual promo-propaganda-porno show for the parents & alumni—the Deans all are running around that week . . . hoping that everything goes off with the proper pomposity. And we . . . walked out on BUNDY (for Christ’s sake—and Lorene picked him herself, without asking anybody, & later, God help us, she said she DIDN’T F—IN’ EVEN KNOW HE WAS DR. STRANGELOVE, altho she did say she had heard there had been this disturbance in Viet Nam) . . . The 2 of us spoiled it all for her & it was so goddam sweet . . . SHEE-IT.

Of course, by the time that was written, Rogers herself had become the hottest political issue on campus. Right on the heels of the salary controversy, the UT regents named Rogers president, even though a student-faculty advisory committee had repeatedly refused to endorse her. On Friday, September 12, 1975, the largest crowd of students to gather since the glory days of the antiwar movement listened to speakers denounce the appointment. The first and, according to the Daily Texan, most warmly received orator was Tom Philpott. “It is our responsibility to teach the deans and chairmen by our example,” he told the crowd. A letter to regent Tom Law written the next Monday is vintage Philpott, full of emotion and high rhetoric:

Dear Tom

Everything is chaotic, and I haven’t had any sleep in two days. This is Monday morning; I’m to debate [regent and former governor] Allan Shivers tonight . . . It’s important for you to understand how negative the atmosphere has been on this campus for years, how beaten, how defeated the faculty has felt, how cynical most people were about . . . the judgement and the honor of the Regents. . . . What we need here is a strong student body, a strong faculty, strong Chairmen and Deans, a strong President, and a strong Board of Regents. And I mean morally strong . . . I am angry about this: I expressed these views for years, and I was ridiculed and not taken seriously and thought something of a chump, somebody who would grow up eventually and learn how it is. I never could accept that and now that I have done something to help turn it around I never want to see it go back . . .

That night, Philpott alienated even some of his own followers by clowning his way through the debate with Shivers. The Texan reported that at one point Philpott cried and that at another Shivers stopped to rebuke him for making faces. Perhaps exhaustion was taking its toll; perhaps Philpott’s manic-depressive illness—characterized by wild swings between elation and despair—was emerging. In any case, Lorene Rogers stayed on as UT president. The protest and the loosely organized boycott that accompanied it were doomed just as surely as Philpott’s suit against the university.

Even so, the battle had its comic elements: tucked away in Philpott’s files is a charmingly childlike student drawing, “ELECT PHILPOTT for responsible, honest & sensitive University Gov’t,” it says above a smiling likeness of the candidate. “Political announcement paid for by the UT committee searching for a real president.” And at the bottom: “Hang in there, blue eyes.”

Hang in he did, if just barely. His marriage to Anne was beginning to unravel. While he took on the University of Texas, she delved more deeply into political work. “The marriage was very rough on her,” Tom concedes. “There she was, living with an undiagnosed manic-depressive who was going through one hell of a beating after another on campus. And something happened to me—I wasn’t sure that I loved her anymore the way I had.” They separated from Thanksgiving of 1975 through the following June.

Governor Dolph Briscoe presented Philpott with a new windmill to tilt at early in 1977, when he appointed three of his political cronies to the UT Board of Regents. Philpott led a drive to block their confirmation by the state Senate, circulating a petition to faculty and students, lobbying at the Capitol, providing background on the appointees’ political peccadilloes to liberal senators, submitting editorials and open letters to the Daily Texan. But the Senate confirmed the appointments before Philpott could gather a quorum —15 per cent of the faculty—to meet and vote on a resolution against them.

Meanwhile, Philpott was falling apart. He collapsed several times—in a photocopy shop, at a McDonald’s, at the theater. Finally he checked into a private hospital, where doctors diagnosed him as manic-depressive and prescribed tranquilizers and lithium. But even as his medical condition improved, his marriage broke up for good. Philpott found himself living one of the clichés of academia: he fell in love with a student. Her name was Louise Epstein, and she was the twenty-year-old daughter of a UT anthropology professor. She was also separated from her first husband, whom she had married at eighteen. Anne insisted Tom choose either her and the children or Louise. Instead he chose a potentially fatal dose of lithium, but his son Paul and Louise got him to a hospital in time to save him. In October 1978 Tom moved in with Louise. He and Anne were divorced the following May; he wed Louise that October. It was, Louise says half bitterly, “the scandal of the century.”

“Anne was beautiful and she was in a wheelchair,” Tom says. “I think people had romanticized us as this fairy-tale couple. After the divorce most of our friends never invited me into their homes again.”

In 1979 the professor whom many students had credited with changing their lives had his life changed by a student. John Kells was only nineteen, but already he was an accomplished television reporter. Kells and another reporter, David Glodt, had just made Boys for Sale, a one-hour documentary about runaways who lived on Houston’s streets and survived by selling themselves to pederasts. When Philpott learned of the film he asked to see it. “I was devastated,” he says. ‘The suffering of these children goes beyond poverty, beyond anything I’ve ever known.”

Philpott began spending weekends in Houston, observing and interviewing boy hustlers. He shelved two years’ worth of research on the Molly Maguires, a radical Irish American coal miners’ organization, and began gathering material for a book about street children. Kells got a job as a newsman in Houston; he and some of his colleagues drove the streets of Montrose in their off hours, trying to help boys find shelter, jobs, ways to get out of “the life.” Late in 1979, when the Daily Texan ran articles about two incidents in which men had been charged with sexually abusing boys, Kells and Philpott contacted Gary Fendler, an editor at the Texan, and Mark McKinnon, a reporter.

“It was all very clandestine, very secretive,” McKinnon remembers. “At that point nobody was supposed to know about Kells’s film, but they arranged a private screening for us. Then they started telling us about how people investigating child prostitution had been kneecapped and had acid thrown in their faces. It got pretty crazy. Philpott said his kids had been followed.” Later, Philpott told other friends other ominous tales: that the prominent and wealthy men who profited from organized boy prostitution had spied on him and sent emissaries to provoke him into violent confrontations; that his phone had been bugged and his apartment repeatedly broken into; that one day as he was riding down the freeway a passenger in another car pointed a rifle at him; that his colleagues in the investigation had been shot at and had hired bodyguards to protect themselves.

In the winter of 1980 Philpott’s elder son, Paul, moved in with Tom and Louise. Having him in the apartment compounded the stress of their already hectic lives. Louise, outwardly the calmest and most matter-of-fact of women, was struggling through graduate school; Tom was deeply immersed in his research on boy hustlers; both of them had to cope with the belief that his life was in danger. Louise was fond of Paul, but the three of them were living in very close quarters and the situation wasn’t working. Tom curtailed his work in Houston and announced that he would no longer teach the mammoth “American Experience” course. It wasn’t enough. In June 1981 Louise moved out and filed for divorce.

“It was good for us to split up,” she says now. “I had gotten so caught up in the terror that it had made me combative. I think the only reason I was able to survive the divorce was that I’d prepared myself for Tom’s death.” Suddenly, unexpectedly, her eyes fill with tears. Suddenly she doesn’t seem nearly the rock one friend aptly described her as. “Some nights, I used to lie in bed shaking. But once you really face the possibility of death you just begin living day by day. I’m not afraid anymore.”

On the evening of October 27 Louise quarreled with her new boyfriend. As he drove away, she went to the phone to call a woman friend. Instead, she found herself dialing Tom’s number. He told her he had been ambushed and shot. She went to his apartment and persuaded him to let her take him to the hospital. The rest is history. Before the year was out they were fully reconciled. Around Christmas Paul went to live with his mother again. Louise and Tom remarried on March 17, 1982—Saint Patrick’s Day.

Today Philpott concedes that his memory of the attack is hazy. He says he was standing at the kitchen sink when he heard a noise in the bedroom. He thinks there were two men, he thinks they were white, he thinks that during the struggle for the gun they tried to put it to his head and make him shoot himself. (He speculates that they chose that course because he had made suicide plausible by having attempted it.) He says he had made the second bullet hole in the far bedroom wall several months earlier, testing to make sure that in a shoot-out a stray bullet would not penetrate his son’s room. Believing that his enemies had previously entered his apartment at will, he does not think it odd that the police found no signs of forced entry after the shooting. And his conviction that the ringleaders of organized child prostitution ordered the attack was bolstered in March when a professor from Northern Illinois University was shot to death while doing research on boy hustlers.

For their part, the detectives on the case say they are bothered by several incongruous pieces of evidence. Philpott says just one shot was fired, but they found two shell casings. And both of the bullet holes looked fresh to them. They were not notified of the shooting until Louise signaled to a patrol car on the way to the hospital. They found no fingerprints or other physical evidence to give substance to Philpott’s story of intruders. But most of all, they’re miffed that he won’t take a lie detector test. Until he does, they’ll continue to suspect that he shot himself for publicity or sympathy, or that he was wounded in a domestic quarrel.

As matters now stand, there’s little likelihood that the case will be solved. The only thing that is clear is that the victim and the police don’t much trust or care for each other. But how much of their mutual suspicion may have existed before the shooting is anybody’s guess. We are dealing here, after all, with a self-appointed crime fighter who says a hideous problem has gone undetected or been willfully ignored by the police—not the type of guy your average cop on the beat is likely to be fond of.

Philpott’s critics have treated his story of would-be assassins with unconcealed disdain. Even his friends regard it with palpable anguish and confusion, and he knows it. “Before October I didn’t have all kinds of people looking at me sideways and whispering,” he says bitterly. But if the truth be known, his admirers—and he still has many—had wrestled with ambivalence even before the shooting, fearing that Philpott is a compulsive publicity seeker, a determined martyr racked by Irish Catholic guilt and still struggling, as one dryly put it, “to get over the Potato Famine.” And Philpott doesn’t make it easy for them to bury those doubts. On the day after the shooting a longtime friend decided to attend Philpott’s lecture class; he walked in to find a photo of Philpott himself projected on the screen.

“My roommate and I used to sit in his class and doodle bleeding hearts in each other’s notebooks,” recalls one former student. “And yet …” And yet. The one thing almost no one denies is Philpott’s ability to teach. Yes, he is emotional, he is a demagogue, he is easy to manipulate, concede many students. And yet, they add, he held my attention and he got me to think.

”He makes freshmen want to go on to be sophomores,” says Mark McKinnon simply. Then he broods for a minute. “Tom was so popular and in the center of things. And now he’s on the fringes, like the catcher in the rye.”

And not only because of the shooting. The early eighties have provided Philpott with a full complement of less-than-popular causes. In 1980 it was the arrest and prosecution of two dozen Iranian students who had interrupted an on-campus speech by a former Iranian ambassador. Nineteen eighty-one brought El Salvador, edgy confrontations between American and Palestinian students, and the suspension of a radical grad student’s teaching duties. Nineteen eighty-two dawned with socialist government teacher Al Watkins being denied tenure. Philpott presented the Faculty Senate and the University Council with eight separate resolutions in behalf of the Iranian dissidents alone. Two very general calls for administrative restraint eventually passed after protracted debates, which Philpott dominated. (“Think of that tradition called OU weekend,” he chided slyly at one point, “when the administrations of this university, the University of Oklahoma, and the city of Dallas combine to permit what would otherwise be defined as a mob to do what another night would be called riot. This is dealt with with discretion, mildness.”) Philpott also testified at the Iranians’ trial; twelve were convicted and all appealed.

Like any compulsively outspoken figure, Philpott had always been jeered at in some quarters. But championing Iranians (in the midst of the hostage crisis, no less) and later Palestinians was another matter altogether. It made him, as he himself puts it, odious.

Philpott from five angles, scene one: “Not Another Viet Nam,” pleads one sign. “Murder Will Out—So Should U.S. of El Salvador,” warns another. Organizers at a table hand out other signs to the ragged group of perhaps 150 protesters gathered on UT’s West Mall. At the fringes of the rally a young man wearing a “U.S. Out of El Salvador” T-shirt reads the Daily Texan, ignoring the speakers and musicians who troop to the microphone —a Viet Nam veteran, an Arlo Guthrie–style folkie, a Latin combo, two members of the Afro-American Players. Philpott stands unnoticed near the center of the crowd, not sure whether he’ll be called on to speak. The rally’s organizers had approached him, but they admitted when he asked that yes, it had occurred to them that he might be a liability rather than an asset, what with having been so visible for so long and all.

At ten to one the tower carillon goes wild, drowning out the Afro-American Players’ chant. At one o’clock precisely, the driver of the university sound truck pulls the plug on the protesters’ microphone, and Philpott adjourns to the Cactus Cafe to kill time until a three o’clock march on the Capitol. Midway through his second gin and tonic he’s accosted by a young couple at the next table. They want him to explain the Viet Nam War. Why did we lose? they demand eagerly. Why are so many of the vets screwed up? What was the Tet offensive? As the hour edges toward three he gently but not regretfully disengages himself from them. “That same guy latched onto me yesterday,” he confides with a slight shudder. “It happens all the time, but it’s a little scary when they’re so intense.”

The marchers form two lines—perhaps fifty Middle Eastern students and a dozen Americans. Philpott attaches himself to the end of the procession, awkwardly holding at his side the sign he has been handed. “One, two, three, four,” chant the students, starting down the Drag. “U.S. out of Salvador!” The scene at the Capitol is more or less a replay of the one on the mall, only with fewer people around to ignore it.

Dusk is falling and Austin’s white-collar work force is streaming out of downtown as the marchers walk down Congress Avenue to the river for a candlelight vigil. They hunker down on a grassy slope and Philpott addresses them through a bullhorn, struggling to make himself heard over the steady roar of traffic. “This is a day,” he says, “for commemorating the deaths of thirty thousand brave people. People like us—we are a revolutionary people, too. It is a crime that this tyranny continues. It is a crime that this suffering continues. It is a crime that we of all people not only tolerate but support it. This war will poison us who stand by and watch it.” When he finishes the protesters move to the bridge, where they huddle in little knots, trying cheerfully but vainly to shelter their guttering candles from the wind.

Scene two: History 350L, “Children and the City Streets.” It’s the first day of class, and about thirty people are crowded into a seminar room meant for fifteen. “Three hundred people tried to sign up for this class,” Philpott tells them. He asks some students to give up their places in the class to bring it down to manageable size. “Four hundred people tried to sign up for this class,” he reminds them. (Oh, well, what’s a little exaggeration among friends?) At last four or five leave. Philpott asks each remaining student to give a brief autobiography and tell why he’s interested in the course. “I’m in love with you,” offers one middle-aged woman.

“I really don’t know how to teach this course,“ Philpott confesses to them. “The literature on hustling is very weak, I think partly because blindness to the problem is conditioned in this society. If you go over to the Graduate School of Business you’ll get the impression that American society is perfect—and getting better. They have no conception of what happens as darkness begins to fall in any American city.” He stares moodily into the dusk outside the classroom window, perhaps contemplating the pain, and the isolation, that awareness brings. “To a person in the academic community,” he says at length, “one of the most intimidating things is the fear of being thought naive or prudish. All anyone wants to know is ‘What’s wrong with these reformers, anyway?’ If you’re well intentioned, if you try, you get nailed to the cross.”

Scene three: office hours. Like his apartment, Philpott’s tiny office in the history department’s not-so-gracefully aging Garrison Hall is a marvelous hodgepodge: a Chicago White Sox pennant; Barrientos and fair housing campaign stickers; three photos of Martin Luther King; six photos of Bobby Kennedy, one taken immediately after he was gunned down; pictures of immigrant-laden ships; portraits of the Kent State Four; two of the seven teaching awards he has won over the years; movie posters for Cool Hand Luke, Bound for Glory, Serpico; a sublimely shabby brown armchair; yellowing stacks of student exams; the armless statue of a black groom, “emancipated,” Philpott says, from a fraternity house at Centenary College in Shreveport.

Philpott holds office hours from one to five. Today, the first three and a half hours are monopolized by students either complaining about last semester’s grades or trying to talk their way into his already overflowing courses for the new term. “I’m just looking for a way to make this semester worthwhile,” one dewy-eyed freshman pleads.

“My friends told me he makes history just like a soap opera,” she confides as Philpott turns his attention to a heavily made-up woman who has barged in to demand a grade change. “You need to raise my grade,” the newcomer tells him impatiently. “I’ve got to have a two-point-two-five average or I can’t get into my marketing classes.”

Next, he spends half an hour with a male student, passionately discussing the merits of his “America Since 1865” essay final. (The question: was the Viet Nam War a just or unjust war?) “I don’t care about the grade,” the student insists. “I just wanted you to read the paper.” Philpott changes his grade to an A anyway, even though the teaching assistant had awarded only a 78 on the final and an 84 on the midterm. As Philpott is filling out the grade-change form, another man sticks his head in the door. Philpott greets him warmly and asks if he’s still working for the Peace Corps in Washington. They reminisce and, after a few minutes’ calculation, established that the visitor took Philpott’s “American Experience” course in 1972.

At about four-thirty, Philpott is alone. A young man slips in and perches on the edge of a chair. After some halting small talk, it emerges that the student is there because he’s heard of Philpott’s course on runaway children. “I was a male hustler in New York,” he says softly. Philpott nods sympathetically and spends the rest of his day listening to the young man’s labored, heart-rending confession.

Scene four: the regents’ boardroom. University of Texas System offices. It’s half past noon, the regents have just adjourned. Laughing and talking, the well-fed, well-dressed staff and administrators head off in search of lunch. No one takes much note of the small, confused band of students—and one professor—huddled in a corner, dwarfed by the cavernous room with its paneled and brocaded walls, gold chandeliers, and velvet draperies. Actually, the kids are lucky to be there at all: they had come hoping to talk to the regents about the fate of government teacher Al Watkins, but the security guards downstairs wouldn’t let them near the meeting at all until they promised they wouldn’t cause a disturbance. Now it’s clear that the regents have slipped through their fingers, and they’re at a bit of a loss. At last they corral the two or three reporters still present and hold an impromptu press conference, lounging in the regents’ high-backed chairs with all the relish of five-year-olds trying on Mommy’s and Daddy’s clothes. Each representative makes a polite speech on behalf of his or her organization; they applaud one another sweetly as three bored UT cops munch on doughnuts. They ask Philpott to speak, too—he’s here, after all, at their request.

“I’m a colleague of Al Watkins’s,” he says gravely. “I’ve taught with him. I’ve seen him teach in the classroom, and I’ve watched him teach in the wider sense, outside the classroom. He has performed the greatest service I think any professor at this university can perform: he has taken great risks in public. I’m heartened to see UT students organizing to do something worthwhile. And this is worthwhile,” he says, earnestly addressing his handful of listeners and the opulent, empty room.

Scene five: home again. These days Tom Philpott doesn’t much like to talk about his shooting. And he flatly refuses to discuss the stories about threats against him. “All that cops-and-robbers stuff is only a distraction,” he insists. “Death is nothing. I’ve never feared death—only dishonor. And besides,” he says, “having gotten shot is probably the best insurance I could have.”

Which is fortunate. Because, he says, despite the whispers that he suffers from a martyr complex, “I want to live. More than anything I want to try to live normally, to be a little bit merry.” To shield himself from criticism, he reaches for the mantle of history. “One enduring theme of American life is the alien amidst the tribe. The tribe transgresses, and in order to recall it to itself, the reformer must become an outsider; he’s forced out by those he would redeem.

“I said I’d never leave this place until I made one real improvement.” And has he? He laughs. “It’s too hard to tell.” He pauses, then grins. “Actually, I’d kind of like to be buried in the stone of the West Mall, like Jack Reed in the Kremlin.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin