In 1994, as he ran against Ann Richards for governor, then-businessman George W. Bush released a campaign ad targeting four social ills in Texas: rapists, child molesters, New Yorkers, and Californians. The sixty-second spot opened with black-and-white footage of a man abducting a woman at gunpoint in a garage, over which Bush espoused his tough-on-crime platform. It concluded, curtly, with the future governor saying that he did “not want Texas to look like New York, California, or anywhere else.” In that regard, the ad was a success on its own terms: the alarming abduction footage did not look much like California or New York, mainly because it had been staged in the Lone Star State. It was such a good non-Hollywood production that Pete Wilson, the Republican governor of the Golden State, used the same scene in a campaign ad as he sought reelection by touting his tough-on-crime first term.

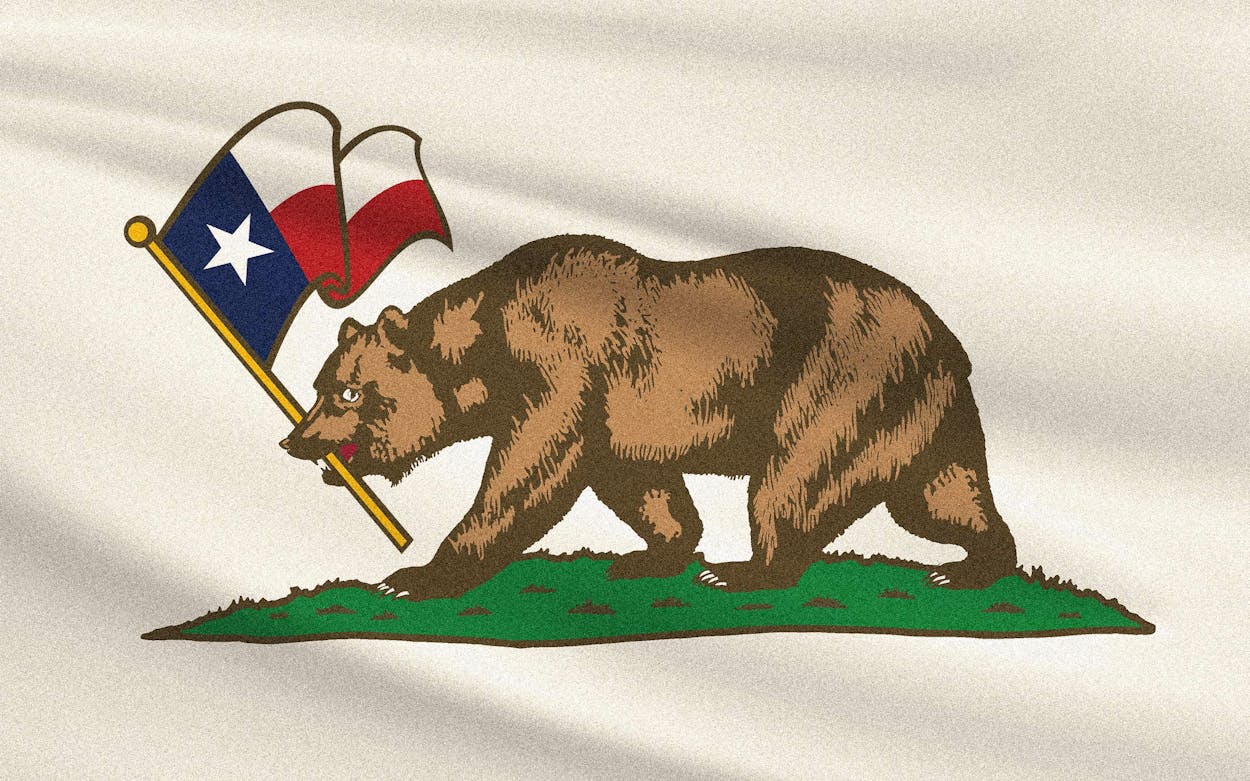

Bush’s ad, which was concocted by a Los Angeles–raised media consultant known for his “laid-back California surfer” affect, exemplifies much of the recent history of California-Texas relations. For decades now, Lone Star State leaders have served up contrived anti-California posturing. Governor Rick Perry proselytized for the “Texas miracle”—the idea that loose regulations and low taxes fueled the state’s tremendous economic growth and superiority even through recessions—but once confessed to wanting to retire on the West Coast. His successor, Greg Abbott, proudly raised money off the slogan “Don’t California My Texas,” then welcomed California businesses and transplants and bragged about how they “fit right in.”

Indeed, for all the anti-California messaging, just about everywhere you look in Texas now, you’ll see California. Outside Austin, Tesla is constructing a factory for electric vehicles, even though you still legally cannot buy any of the cars it makes in Texas, where state law prohibits manufacturers from selling automobiles directly to consumers. Statewide, there are now more locations of In-N-Out Burger than Buc-ee’s. Heck, even Waco has become a pilgrimage site for Golden State surfers, who have abandoned Newport Beach for a state-of-the-art Central Texas wave pool. And in higher education—long the reported nexus of the infiltration of West Coast values—Steve Sarkisian, who grew up in the Los Angeles area and cut his football-coaching teeth at USC, has transported California-style winning percentages to the Big 12. (Meanwhile, his more successful counterparts in the conference run a version of what was known in the eighties as the “West Coast offense.”)

By now you’ve heard it all. How, over the past decade, California businesses have been relocating here in droves, enticed by low taxes, a lax regulatory environment, and the Texas Enterprise Fund. How nearly 700,000 Californians, who remember the Alamo Rent a Car, have come with them. How they’ve been drawn, variously, by affordable housing, the smell of freedom (everywhere but Austin), and the better Mexican fare (“You may all go to Taco Bell and I will go to Texas”). And, of course, how their arrival has been received with some curiosity, and plenty of disdain.

So let me say what state leaders want to say, but won’t so easily admit: send in the Californians. Then send in more. Don’t stop until everyone here is cuffing their boot-cut jeans and Beto O’Rourke is treating national politicians to a local meal of a Double-Double Animal style. Before proceeding, a disclosure: I came to Texas from California, though I am not originally from there. (When I applied for Texas plates, the Department of Public Safety staffer reviewing my California driver’s license asked me if anyone still remained on the West Coast.) Because California has always embraced newcomers, whereas Texas looks for traitors, my having lived there for a bit and here for a bit makes me, essentially, Californian. I have also experimented with a man bun, worn highlights in my hair, find vocal fry melodious, and prefer failures of the power grid to stem from wildfires and not the negligence of state leaders. But my case for Californians isn’t an aesthetic one.

The case begins with the reason Texas politicians secretly love Californians: they have been crucial to Texas’s economic growth, and will be key to sustaining it. Perry wasn’t entirely off base in calling what happened in Texas over the last few decades a “miracle.” Since 1990, Texas has led all states in GDP growth, and in the past decade in particular it has created millions of new jobs. But as with many miracles, the state’s success might more properly be understood as a magic trick—the secrets to which state leaders have been apt to conceal. While a business-friendly environment certainly helped, what allowed Texas governors to walk on water, so to speak, was a glass California catwalk. John Hryhorchuk, vice president of policy at Texas 2036, a think tank concerned with meeting the challenges of population growth by the state’s bicentennial, put it to me plainly: “One of the dirty little secrets of the Texas miracle is that much of the human capital growth that has fueled the economic growth over the last twenty years has been the result of migration.”

California migration, in particular. The Californians who’ve coasted here have brought high-wage jobs with them. Steven Pedigo, a professor at the LBJ School of Public Policy at the University of Texas at Austin, told me that “we sort of needed those California enterprises and that California talent to catalyze a lot of the innovation that’s happened here.” The relocation of tech companies and workers has allowed Texas to develop new types of jobs, and eventually a “thick labor market,” as economists call it, so that new companies need not launch in Silicon Valley to find workers any more than they need travel to the West Coast to seek capital investment.

But still, Texans may ask: why not tell the Californians to stop coming now that they’ve delivered growth? It might be tempting, but the fact is, Texas still needs migrants to keep up the pace of its economic boom. Economic growth is driven by one of two factors: increasing productivity (output per hour worked) or increasing the number of workers. Across the country, productivity is still growing, but at diminishing rates (California’s growth far outpaces Texas’s). Meanwhile, Texas’s workforce now faces an unprecedented obstacle: the state’s birth rate has declined markedly—by 20 percent—in the last fifteen years. All the children Texans didn’t have over that period would have been entering the workforce in a few years. Couple that with pandemic-exacerbated retirements of boomers, and the Texas labor force could soon have a California fault line–size gap.

While any migration would suffice to fill it, Californian migration has the most utility to Texas politically, which brings us to the second half of our case: representation matters. Congressional representation, that is. California is the only state with more U.S. House members than Texas. That representation is zero sum: one state’s gain is another’s loss. Though Texas’s House delegation grew by two and California’s shrunk by one after the 2020 census, the Golden State still leads by fourteen representatives. A mass Californian migration that tilts congressional power to Texas could matter greatly—especially if Texas politicians decide to abandon their obsession with culture wars and focus instead on bringing home more federal money for use here. So if you want federal dollars to go toward the building of the Ike Dike, and couldn’t care less about whether California’s coastal highway, U.S. 101, adds a fifth lane, dial an Angeleno and invite her to subsist on a diet of Boomsticks rather than Dodger Dogs.

Of course, Californian migrants do bring challenges with them. They have already caused the cost of living to explode here, making many Texas neighborhoods unaffordable to those who’ve dwelt there for years. “All boats rise,” as Pedigo put it, “but not all boats rise enough and rise fast enough to deal with the externalities.” That inequality is also being fueled by a burgeoning issue that Hryhorchuk, Luis Acuña, and Merrill Davis—all staffers at Texas 2036—identified when we talked: there’s a wide gap between the educational achievement and earnings of newcomers versus natives. Migrants from all over the U.S. are two times as likely as native Texans to have a bachelor’s degree, according to data Texas 2036 has compiled.

These are problems with solutions. I’m well aware that Californians aren’t exactly in a place to give advice on this—the Golden State’s failure to handle a booming population and abate growing inequality are big reasons why so many are fleeing the West Coast for here—but many Texas groups, including 2036, have been working on meeting the challenges. At the local level, combating soaring costs of living requires changing zoning laws to quickly build more housing, and investing in transportation infrastructure to deal with bloating metropolises. Statewide, leaders can tackle the widening gap between natives and newcomers by expanding access to advanced courses in elementary and high school, incentivizing high schools and community colleges to teach in-demand skills, and making college more affordable for first-generation students. There’s time to act—if only leaders could put aside the culture wars and start solving problems. But the one potential solution to booming population that has proven to fail is nativism: if the last two decades have proved anything, it’s that mocking people who move here won’t stop them from doing so.

But what about that other nagging problem—what if California transplants really won’t fit in? If we’re being honest, Texans needn’t concern themselves too much. If you’re worried that Californians will turn Texas into a bastion of big-government liberalism, worry not: the best evidence so far suggests they won’t. Exit polling from the 2018 U.S. Senate election found that Ted Cruz lost to Beto O’Rourke among native Texans, while handily beating him among those who’d moved to the state.

If you’re worried that Californians are notoriously eclectic and uniquely convinced of their exceptionalism, and thus won’t fit in, take solace: that’s exactly why they will. And if you believe the Golden State to have some ineffably alien quality that precludes rehabilitation here, recall that Texas legends such as Troy Aikman, Tony Romo, and even Lyndon Baines Johnson once fondly called it home—and that the latter long extolled the merits of what a few months living in the state taught him. As for other aesthetic concerns, there are fixes: for one, Californians can cover their man buns with Stetsons.

For as long as Californians have been charging into Texas, worrywarts on both sides of the exchange have proclaimed their dispositions irreconcilable. Way back in 1994, when California first grew fearful of a mass Texodus, it launched a $12 million ad campaign to convince residents they wouldn’t fit in in the Lone Star State. “You’ll need big boots to wade through all the promises that states like Texas are making to Californians,” the ad said. “What they still haven’t promised, though, is a surefire way to fit a gun rack on a convertible.” It then enumerated a list of problems supposedly endemic to Texas: “What they don’t mention is their own subzero weather, alternating with three-shower-a-day humidity. Along with hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and mosquitoes that require runways to land.”

At the time, Governor Richards accurately wrote Governor Wilson that it was a “silly ad.” Texas had business opportunities. It knew how to balance a budget. And Californians would easily find themselves at home here.

She was largely right. The ad might have been prescient in recognizing the problems Texas might someday face with subzero weather. But as for other concerns: Mosquitoes? Texans can teach Californians how to spray some Off! Humidity? Educate them in the glories of air conditioning. And gun racks, if they’re so inclined, can easily fit in a Tesla.