When Jairon Abraham Cruz left Cuba in early January, he had already spent years looking north toward the United States, telling his mother about his dreams of living in Florida, where his grandmother already resided. In October, the seventeen-year-old had posted a photo of himself on Facebook dancing with an American flag, the Havana skyline silhouetted in the sunset behind him. He hoped to become a dance influencer on YouTube and TikTok in the states. Then, around New Year’s Day, as Cuba had slipped into a historic economic crisis and the government cracked down on protesters, Cruz’s mother and her husband decided it was finally time for them, Cruz, and their daughter to leave. When the family’s journey to the U.S. began, it felt to Cruz like the start of a new life. In reality, the teenager was living out his final days.

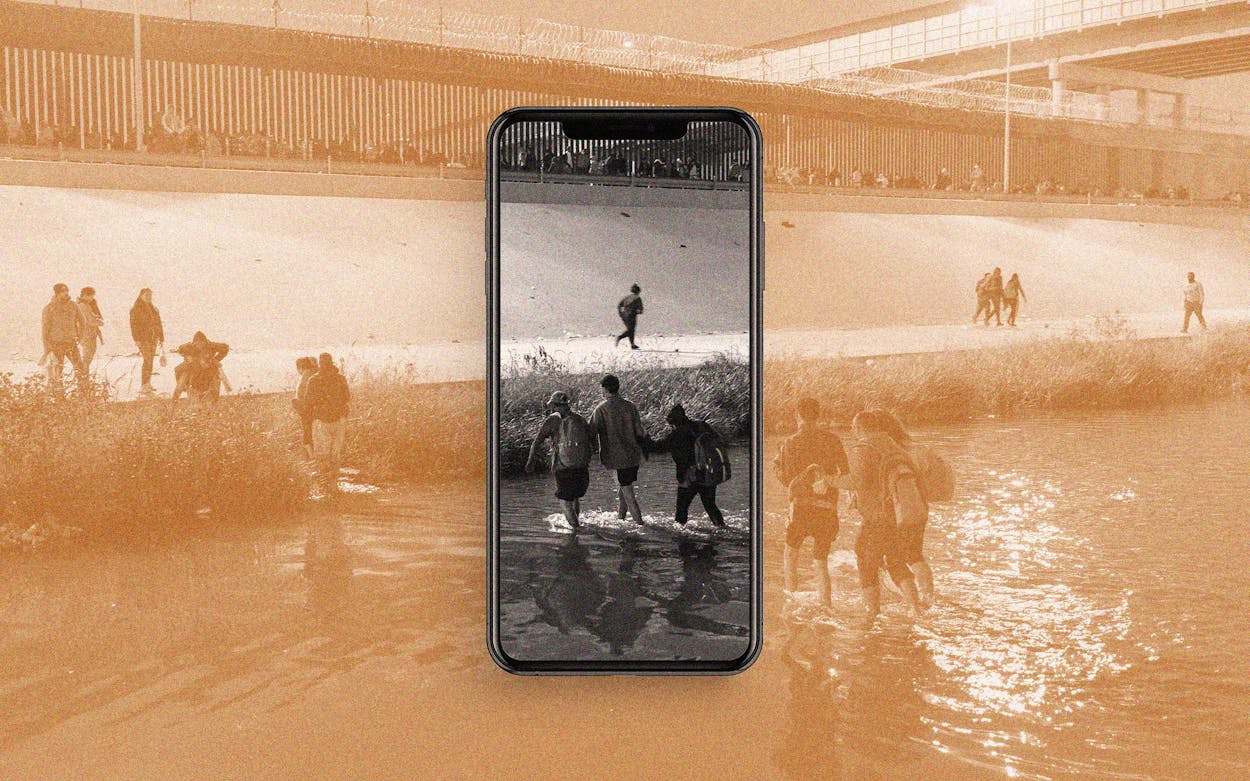

For generations, Cubans have fled the country, pushing off from the island in inner tubes, on Styrofoam boats, and even in old trucks outfitted with propellers. Rather than make the traditional voyage across the Atlantic to the U.S., however, Cruz and his family left in a way that’s become more common in recent years, as the U.S. Coast Guard has increased enforcement and repatriation of Cubans intercepted at sea. They traveled first to Monterrey, nestled in the steep peaks of the Sierra Madre range in northeastern Mexico, with the intention of traveling nearly 150 miles north upon arrival and requesting asylum in the U.S. at the official port of entry in Laredo.

The family planned to travel quickly and avoid spending time in the notoriously dangerous Mexican border city of Nuevo Laredo, but in Monterrey, they learned about a new requirement for asylum seekers arriving on the U.S. border. Talking with their relatives already living in the U.S. with citizenship, the family learned that, if they simply arrived in Texas and attempted to request asylum, agents with Customs and Border Protection (CBP) would immediately deport them, no matter what. “My family and I were on our way to the border when the new law came up,” Cruz’s mother, Yamisleidys González, said over text.

Seeking to crack down on border crossings, both legal and illegal, President Biden announced on January 5 a new requirement to greatly limit the number of migrants who can officially request asylum. Today, those fleeing persecution need to first use an official CBP app, CBP One, to make an appointment at the border. (CBP One was first rolled out in limited cases in 2021 but was not a broad requirement until January.) Unlike many asylum seekers, González had a smartphone, and she managed to use the new system. But, while CBP was releasing dozens of new appointments every morning, thousands of asylum seekers were waiting to cross and slots filled up almost instantly, so the earliest that González could schedule one for her family was weeks away, on February 3.

The family booked a hotel in Monterrey, a relatively prosperous industrial city that’s considered one of the safer places in northern Mexico. Their downtown dwelling, Hotel La Silla, had seen better days. But the accommodations were far better than those of thousands of asylum seekers who sleep on the streets in border towns, where their foreign accents betray their vulnerability to cartels and kidnappers.

Two weeks later, in the early morning, the family heard shouting in the hotel hallway—at least two men were screaming something about Colombians. Someone suddenly began trying to force open their hotel room, and Cruz, closest to the door, rushed to hold it shut as González picked up her four-year-old daughter and ran to the bathroom. She heard two gunshots fired through the door. The men grabbed her husband, Gabriel Fernández, and pulled him out of the hotel, though he eventually fought them off. When González came out of the bathroom, she saw Cruz lying on the ground. He passed away in front of his mother and sister. He was the first asylum seeker to die while waiting for an appointment on CBP’s app.

“He loved to dance and make everyone laugh,” González, said. “He was so young.”

News about Cruz’s death reached Priscilla Orta, an asylum attorney in Brownsville, the morning after the teenager died. It broke her down. For weeks, Orta and her nonprofit, Lawyers for Good Government’s ‘Project Corazon’ initiative, which provides aid to immigrants, had worked with asylum seekers on the Mexico side of the Rio Grande Valley, helping them use the new app. At first, she’d been optimistic about the technology. CBP One had the chance to introduce some order to the immigration system and to finally give asylum seekers the basic information they all craved: how to do things the right way.

For most of the past fifty years, U.S. law has guaranteed that any foreigners who present themselves to authorities on U.S. soil have a right to seek asylum; our country will let them in as long as they can prove they were fleeing persecution or danger. For decades, CBP agents would interview newly arrived asylum seekers on the border and, if their claims were deemed credible, allow them to stay in the U.S. until their court hearings to prove their cases. But in March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first forced shutdowns in the U.S., the Trump administration began summarily expelling almost every asylum seeker who arrived on the border, invoking Title 42, a once-obscure federal statute that allows the president to halt immigration during public health emergencies.

The policy continued under the Biden administration, which has expelled more than 2.4 million would-be asylum seekers. The administration tried to end the policy in May 2022, but it remains in effect as it winds through the courts. But the administration has allowed more than 2.5 million migrants into the country, at least temporarily, under normal immigration procedures. Many of these were asylum seekers whom agents deemed “particularly vulnerable,” and who were granted Title 42 exemptions, and have been permitted to cross into the country to pursue their claims in court.

CBP One has massively narrowed the pool of asylum seekers allowed to seek these Title 42 exemptions. Orta got a vivid window into how the new policy works in Reynosa, one of the most notoriously dangerous cities in Mexico, across the river from McAllen. Since the new regulations went into place, Orta and her team have seen multiple torture victims—some with clear evidence of physical injuries—turned away at the port. CBP officials told them they’d have to use app. “I do not think this happened because our local officers are heartless,” Orta said. “I do not—I think this is a conscious decision by the administration.”

The process of using the app is theoretically straightforward. On CBP One, asylum seekers first certify they meet certain “vulnerability criteria.” Then, they enter biographical information and take a facial photo, using the selfie camera in video mode (a CBP spokesperson said this video-selfie feature is to ensure “liveness”—in other words, that a real person is taking the photo). Finally, they book official appointments to meet with CBP agents to review their cases at one of eight ports along the border. (Five of these ports are in Texas: from the easternmost entry point in Brownsville, upriver to Hidalgo, Laredo, Eagle Pass, and El Paso.) If all goes well at these appointments, asylum seekers are released on official parole, with a date to appear in immigration court to make a formal asylum claim, or otherwise make a case against their deportation.

In Reynosa and in Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville, Orta and her team have advised dozens of asylum seekers on how to get appointments through CBP One. When the app works, the system is orderly, and CBP agents at the ports are respectful and efficient. But Orta has found that in many ways CBP One has functioned more like a deterrence mechanism to reject travelers than like a mode of entry. It’s closer to razor wire than to an open gate. Where once the basic requirement for seeking asylum was “fleeing persecution,” now there’s a whole host of additional requirements, among them: having a working smartphone; internet connection to use the app; and the ability to read and write in English, Spanish, or, only recently, Haitian Creole, the only languages the app offers. Many of the most vulnerable do not meet these criteria.

When asylum seekers began using CBP One in January, they also discovered a finicky app plagued with bugs that would often crash. It felt like the digital equivalent of visiting the DMV. Aid workers also quickly noticed a troubling pattern. The photo scan feature struggled to take photos of most users (when I used it at home in Austin, it crashed multiple times, and didn’t recognize my face at first). For users who were Black, especially, it repeatedly failed to work, unable to recognize differences in contrast on dark skin. Speaking on background, a CBP spokesperson acknowledged the bugs, but denied that the photo scan is not working for those with dark skin.

CBP One also has muddled the asylum process. At no point does the app ask users “Are you seeking asylum?” Those arriving for the CBP One appointments are given no interviews and asked no questions about vulnerabilities they listed in the app or about why they’re seeking asylum in the U.S.—they’re simply released into the country on official parole. Their court dates, in immigration court, aren’t even necessarily asylum trials: they’re often deportation hearings, where defendants can make arguments for remaining in the country, including through our asylum system. “That’s the crazy part: nothing in the new [CBP One] parole program requires that you seek asylum,” Orta said. “Somehow, we’ve decided to punish those who arrive on the border, without the app, actually seeking asylum, but we’re going to let in those who may or may not have any particular reason to seek asylum, [including some] who feel safe in their home country.”

Orta added, with a laugh, that she sometimes feels more frustrated with Biden than Trump—under whom policies made more sense: they were all obviously deterrence measures. “At least under Trump, I knew how to work the system,” Orta said.

During the Trump administration, as family separation dominated the headlines, a lesser-known Trump policy later dubbed “Remain in Mexico” affected thousands of migrant families, forcing them to wait for asylum hearings for months, sometimes years, in Mexico, rather than north of the border as was standard practice for decades. CBP began a “metering” policy: at each port, agents only accepted a small number of asylum seekers each day and told the rest to wait. Stuck in cities such as Tijuana with nowhere to go, asylum seekers coordinated among themselves and created “La Lista”—an unofficial, but quite formal, list jotted down in college-ruled notebooks that tracked where each migrant stood in the line to ask for asylum. Almost every week, asylum seekers waiting for their turn reported getting raped, robbed, kidnapped, and extorted in northern Mexico.

CBP One looks like a brave new future, but, in many ways, it’s simply a digital version of those notebooks. Advocates such as Guerline Jozef, cofounder and executive director of the Haitian Bridge Alliance, one of the main nonprofits guiding asylum seekers through CBP One, worries that the app is simply an extension of Remain in Mexico, a Kafkaesque bureaucratic mechanism—like when a pilot says “We’ll be moving in about a half hour” to keep passengers calm during an indefinite delay. She sees it as a way to encourage asylum seekers to wait patiently in dangerous areas for an opportunity that may never come. Jozef has met some families who have tried for weeks to get appointments, to no avail. “If people have to wait a week, two weeks, a month, that’s a problem,” Jozef said. “They are not safe in northern Mexico—people are going to die.”

In Monterrey, Jairon Abraham Cruz did die. In desperation, his grandmother, a U.S. citizen in Miami, reached out to a local immigration lawyer, Wilfredo Allen, for help. As they grieved the death of Cruz and worked to get his body repatriated to Cuba, the family struggled mightily to get the app to work for them. “We got them a new phone; we tried re-downloading the app; nothing worked,” Allen told me, adding that the experience of struggling with the app taught him something. “If you’re in northern Mexico, [the app] will give you a lot of hope. But it’s going to be a difficult road.”

Eventually, Allen contacted CBP, and agents guided him through how to make the app work; the solution involved completely deleting the family’s existing profile and starting again from scratch. In late February, Cruz’s mother and young sister finally made it into the U.S. through a new parole program for Cuban asylum seekers, which Biden had announced at the same time as CBP One in early January.

González’s husband did not cross with his wife and daughter. Two months after fleeing for a better life, he returned to Cuba, to await the return of Cruz’s body.

Correction 3/4/2023: A previous version of this article conflated the experiences of multiple asylum seekers in a paragraph about a Haitian migrant who was turned back at the border. This article has been updated to note that Priscilla Orta and her team members encountered multiple torture victims in Reynosa, who were then each turned away at the port.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Joe Biden