This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Al-Hamdu li-Llāh, Rabb al-calamīn,

al-Rahmān al-Rahīm,

Mālik Yawm al-Dīn.”

(“Praise be to God, the Cherisher

and Sustainer of the Worlds,

Most Gracious, Most Merciful,

Master of the Day of Judgment.”)

Bright-eyed, handsome Charlie Brooks, Jr.—Shareef Ahmad Abdul-Rahim, he called himself—had already said his morning prayer when the guards came to get him at seven on that December Monday. They took him from the Ellis Unit, a maximum-security prison northeast of Huntsville, where Texas’ more than 150 condemned men are shelved, to the Walls Unit, sixteen miles into town. Charlie would spend the last seventeen hours of his life there. The Walls is a red brick structure located on the edge of Huntsville’s business district. Maybe you’ve been there. It is the site, each October, of the prison rodeo.

Just a coin’s drop away from the northwest guard tower at the Walls are the nine cells of Death Row, where, before things got crowded and waiting grew long, condemned men spent their final weeks. It was here, in 1964, that Joseph Johnson, the last convict executed in Texas, said his good-byes. Here, over a period of forty years, the 361 men electrocuted at the Walls prepared to meet their Maker. At the end of the hallway that connects the cells of Death Row is a gray steel door, and on the other side of it is the room where they died.

In the old days all of Death Row was a dull prison gray, like that steel door. In recent years its bars have been repainted in pale yellow, its cells in brilliant blues, whites, and greens. Old Sparky, the notorious electric chair where men were dispatched, sits crated in the hallway. The chair was set aside in 1977 after a Dallas television reporter, flanked by lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union, filed a suit seeking permission to film executions; the Legislature wanted a method less dramatic and less unsightly than electrocution. Lethal injection was the alternative, but in adopting it the Legislature flew in the face of what Texans claimed to have known for a century: that men die best on their feet. That tenet of frontier wisdom got a confirmation, oddly enough, in a report of the British Medical Society.

In 1953 the society studied a proposal for death by injection and recommended against it, not only on narrow Hippocratic grounds but also because the method seemed likely to undermine the condemned man’s sense of self-control and dignity. “Human nature is so constituted,” the society’s report said, “as to make it easier for a condemned man to show courage and composure in his last moments if the final act required of him is a positive one, such as walking to the scaffold, than if it is mere passivity, like awaiting the prick of a needle.” In Huntsville, too, there were men whose observations might have provided reasons for doubt. Chaplain Clyde Johnston of the prison system, who has stood as fourteen men went seated to their deaths in Old Sparky, says that the condemned men usually showed pride and poise, “until they were strapped down in the chair. That’s when we’d see it—this frightened, scared look that would come over their faces, even though, because the guards worked quickly, it didn’t last long.” On the morning that Charlie was moved to Death Row, the men who would be his executioners thought that his last moments of anticipation and agony would pass quickly enough—but nobody knew for sure.

The prison guards brought Charlie’s belongings from Ellis to Death Row in pasteboard boxes, but Charlie didn’t unpack them. Instead, whenever he wanted something, he rummaged in the boxes until he found it. The first item he fished out was a small black clock radio. From time to time he opened one of the dozen cans of Dr Pepper he had ordered over the weekend from the Ellis commissary. Charlie had done a prisoner’s best to stock up on pleasures he might never taste again.

Most of the men who had sat on Death Row, waiting for reprieves or the worst, were murderers, like Charlie Brooks. Only with him, the label didn’t fit neatly. In separate trials, both he and a partner, Woodie Loudres, had been sentenced to die for the 1976 killing of David Gregory, a repairman at a Fort Worth used-car lot. No weapon was ever found, and the authorities never determined whether Loudres or Brooks fired the single shot that sent Gregory to the graveyard. Convicts file writs like horse players buy totalizator tickets, and like horse players, sometimes they get lucky. Loudres did. An appeals court overturned his conviction, and last October he was able to plea-bargain for a forty-year sentence. The Monday last December when Charlie Brooks counted down the hours was only another day toward parole for Woodie Loudres.

The prison’s chief cook came to Death Row that morning to discuss Charlie’s last meal. Charlie wanted fried shrimp and oysters and had let his wish be known nearly a week beforehand. He could have anything in the pantry of the Walls Unit, the cook told him, but shellfish were not on hand. “I thought I got my choice,” Charlie muttered before resigning himself to steak and peach cobbler.

Somber, nervous, and pessimistic, Charlie was waiting for a stay. His lawyers had told him that they’d probably get one, but Charlie, like all convicts, had learned to doubt anything that lawyers and lovers might say. On his own he had pursued his case for six years, through nine hearings, in five courts, before 23 different judges. Charlie’s opinion was that his best chance for mercy lay with a 3-judge panel of the Fifth U.S Circuit Court, which was meeting in New Orleans that morning to reconsider his various appeals. Only a few days earlier, a stay had seemed almost a certainty. Now time and Charlie’s confidence were getting short.

At thirty minutes past noon, Charlie learned by radio that the Fifth Circuit had turned him down. “Well, that’s it. The Supreme Court and all the others will follow what the Fifth Circuit did,” Charlie told Akbar Nurid-Din Shabazz, an American Moslem Mission chaplain for the prison system. Shabazz, an American black who doesn’t really speak Arabic but believes that God does, prepared to play muezzin, calling Charlie to prayer. Though his lawyers would draft appeals late into the night, Charlie decided that it was time to prepare himself to die.

Charlie liked to tell visitors that there were three pursuits in his prison life: Islam, law, and chess. Though he had sought a chess opponent that morning, two guards, Shabazz, and a Christian chaplain, Carroll Pickett, had all declined. Pickett and the guards weren’t familiar with chess, and Shabazz knew he couldn’t give Charlie a close contest. Not until two o’clock did the convict find a willing player, a guard known at the Walls as a skilled hand at the game. It took Charlie half an hour to do it, but he buried the guard’s reputation.

At about four-thirty niece Berrie Jean Mitchell and a Fort Worth Muslim teacher, Larry Amin Sharrieff, showed up to visit. Charlie and his niece talked about childhood days for more than an hour, then Sharrieff led him in prayer, and the visitors were shown out of the Walls. Guards led Charlie to a shower and gave him a set of clothes to replace his prison whites. The last meal was brought; Charlie ate and followed with a toothpick. Because he had requested it, guards and ministers did not disturb Charlie for the next two hours. In solitude, he wrote letters and mused over his life.

Charlie’s past was proof that there is nothing exotic or even exciting about crime or criminals. The findings of the Court of Criminal Appeals show that even the crime for which he was sentenced was exceptional only for its seediness:

The record reflects that on the morning of December 14, 1976, Marlene Smith, an admitted prostitute, thief, and heroin addict, traded sexual services for the use of a car from a used car dealer. She then picked up Woodie Loudres and the appellant at a liquor store on Rosedale Avenue. Smith testified that she and Loudres lived together in Room 15 of the New Lincoln Motel. [The New Lincoln was a Fort Worth hot-sheet inn for prostitutes and a shooting gallery for addicts.] Smith, Loudres and the appellant drove back into the motel, where Smith and Loudres took heroin. The three then drove to the home of appellant’s mother, where they drank. The trio then left, heading for the south side of Fort Worth so that Smith could go shoplifting. . . . As they were driving onto East Lancaster Street, the car vapor-locked and they pushed it into a service station. They were unable to get the car started and, according to Smith, the appellant left the other two and walked to a nearby used car lot to “get a car to test drive” so that the three would have transportation to the south side. . . . Company policy required that customers who walked onto the lot and asked to test drive a car had to be accompanied by an employee. David Gregory, the deceased, was told to accompany the appellant around the block. The record reflects that Gregory was a paint and body repair man. . . . A car identified as the one taken on a test drive from the used car lot was driven into the New Lincoln Motel at about 6:00 p.m. . . . The appellant released a man from the trunk of the car and took him at gunpoint into Room 17 of the motel. . . . Shots were heard soon thereafter.

Policemen summoned by a motel employee arrived around six-thirty. In room 17 they found David Gregory, gagged and bound with adhesive tape and clothes hanger wire. There was a bullet in his head.

In childhood, Charlie Brooks, Jr., was not the sort of kid you would expect to show up, sooner or later, at the New Lincoln Motel. He was raised in the home of a Methodist Fort Worth meat cutter, neither poor nor rich. The youngest child, he was his father’s pampered namesake. The father died just before his son turned fourteen, and the boy inherited the new ’56 Chevy his dad had ordered only days before his fatal coronary. Charlie soon had money, for a pension had been left, and he had wheels. The rest of his story is as common and pitiless as mold.

On cheap streets, Charlie swaggered too much. The knife and bullet scars on his belly were the price he had paid for bravado. He was too showy, as well. On the night of his last crime, he was plumed for memory: a factory-faded denim cap on his head, the kind with zippered pockets in the crown; a moustache that curved back to his sideburns; brown sunshades; one or two earrings, diamond or pearl; a slinky polyester print on his chest; yellow gloves on his hands; and, across his shoulders, a tan top-coat with shoplifter’s “drop pockets” inside. Charlie Brooks was not a criminal of cautious taste or nondescript style. He was a pool hall rooster.

Charlie married and fathered two sons, but he wasn’t around to raise them because he was continually in trouble. In 1962 he pleaded guilty to burglary in Baton Rouge. In 1968 he was convicted on federal firearms charges in Fort Worth. (He had been caught with nothing more exotic than a sawed-off shotgun.) In 1970, charged with burglary and theft, he was sentenced to prison again and sent this time to Huntsville; he was discharged in 1975. Unlike Charles Manson or Gary Gilmore, Charlie Brooks did not grow up in our prisons. He grew in them.

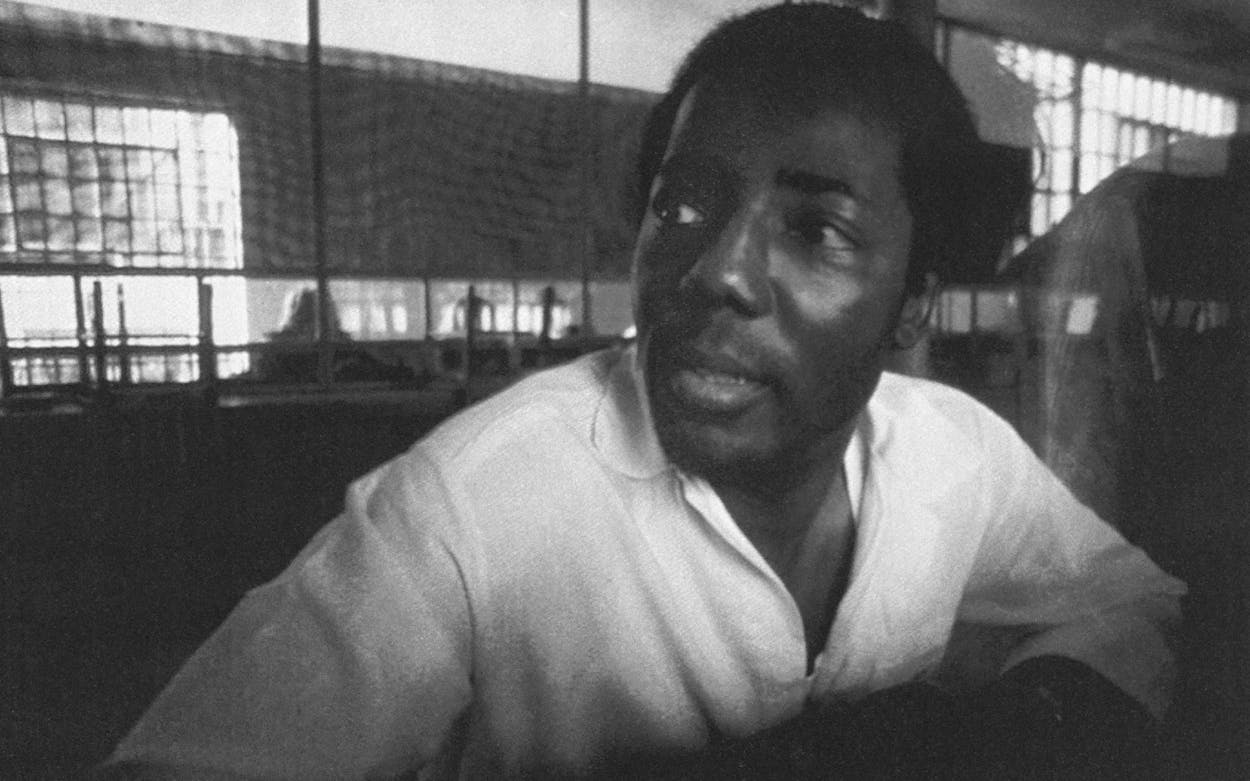

When I talked with Charlie at Ellis last fall, he was not the past-his-prime punk I expected. He had tempered his attitude but had not aged much during his years on the death list. Still trim and in good physical shape, he had only a few strands of gray to show that he was 40, not 25. He was soft-spoken, and his gestures were entirely meek and friendly, like the movements of a dog that is used to being whipped; prison had taken away Charlie’s bravura, perhaps for the second or third time. He was revved up for our first interview, squirming, sparkle-eyed, and full of good cheer.

Charlie wanted to talk about his religion. Three years earlier he’d seen the error of his ways, he said, when he had taken up the Muslim faith. Everybody on Death Row takes the Jesus train, as the convicts call it. The trouble with the Jesus train, and presumably with its Muslim equivalent, is that it starts with a great commotion, a-praisin’ and a-prayin’, but usually stops at the Commutation Station, where its engines turn cold and its passengers leap off. But Charlie insisted that his religious conversion was for real.

“I decided to try Islam,” he said, “uh, just to see what it would get me. I had tried Christianity before, you know, but it didn’t do for me what I wanted.” At first, he told me, he had observed Muslim ritual without particularly believing in it, but within six months—the probationary term he’d given Islam—it had delivered him from a torment. “You know, in here,” he said, “where there aren’t any women, uh, a lot of inmates do homosexual things. The rest of us, well, most of us take matters in hand, so to speak. You know, it’s been three years now,” he said with a slight smile of pride, “since I’ve taken the situation in hand, if you know what I mean.”

Since frankness was the mood, I asked him what I really wanted to know. “Shareef”—I called him by his Muslim name—“What’s the truth about the killing you’re charged with? Who shot that dude, you or Woodie Loudres?”

In a low, tired voice, he told me that he didn’t want to comment on the affair, except to state, “I regret my participation in the events of that day.” It was a rehearsed answer that told nothing.

“Charlie,” I pressed, “they say that Woodie Loudres might have had a pistol too, but you were seen with one.”

“I don’t want to say too much,” Charlie whispered, leaning close and hesitating. “Let’s just say that, uh, you know, the gun could have gone off.”

On other visits our talks returned to his crime, his faith, and his future. The impression I formed was that even though he called himself by a new name, Charlie Brooks wasn’t entirely a changed man. He was still a convict, and convicts shave the edges off of everything, including the True Faith. Charlie didn’t pray toward the east, because there was a wall on that side of his cell; he prayed toward the door, as if freedom were Mecca. His self-taught Islamic tradition told him that he should fast on Tuesdays and Thursday, but on Thanksgiving Thursday he didn’t fast. He knew that Allah commanded Muslims to speak the truth, but he never spoke to the courts about his role in the death of David Gregory. (“I don’t lie about that,” he told me. “It’s just that for legal reasons, see, there are some things I don’t go into.”) Even the Arabic name he picked had the ring of an opportunistic deal. “Shareef Ahmad Abdul-Rahim” translates, roughly, as “Noble Praiseworthy Servant of Allah the Merciful,” as if Charlie, by serving Allah, might ensure His mercy. Allah had forgiven him his past, Charlie said. His implication was that his crime no mattered.

Convicts and steady religion are not an easy mix, because religions have rules that contradict self-interest, and convicts don’t. Given that he was first of all a convict, Charlie was probably as penitent and sincere as was possible. In a prayer he had composed himself, every afternoon he asked Allah to “turn away from me the evil and the indecent morals, for none can turn away from me the evil and the indecent morals but Thee.” Charlie was right that he couldn’t turn away on his own; anyway, he never had. Though he denied that he’d been addicted to heroin, he had played hard with drugs from an early age, and he had never cared how he got high. “If today I’m with the heroin addicts,” he told me, “I’ll shoot some heroin. If tomorrow I’m with the pill heads, I’ll take some pills. If the next day I’m with the wine heads, I’ll drink some wine, and the next day I’m with the alcoholics, boozing heavily with whatever—Scotch, whiskey—that is what I’ll do. But every day it is something, every day it was something.”

When Charlie got loaded, his caution was displaced by bluster. There is, for example, the story of his second appearance before a blazing gun, in 1969. “I really don’t know why I got shot the second time,” he told me, “because this guy, well, I know why, because I had threatened him. You know, I had gotten high one time, and this guy pulled out his pistol, you know. And so I told him, I say, ‘Next time you pull that pistol out on me, I’m going to make you use it.’ But I was loaded that time, you know, because I even forgot about it. So, sometime later, I was high again, and I, well, I didn’t get into it with his little cousin. I was joking with his little cousin and he thought we were serious. And they tell me I said, ‘Is this the second time? Yeah, that’s the second time you’ve pulled that pistol out on me.’ But I know I distinctly remember that I was standing like this, with my hands on my head. Because I didn’t want him to think I was trying—he’s got his pistol on me, see—I didn’t want him to think I was trying to get into my pockets. Not that I had anything. I didn’t even have a knife. So they tell me that I said, uh, ‘That’s the second time you pulled that pistol on me. You’re not going to do it again,’ you see—pow! he shot me.”

In his best mood, Charlie thought that there was nothing to fear in death by injection. He believed that he could set it up to be like the surgery after the first of his bullet woundings. “I remember the first time,” he told me. “I fought the, it was, I think it was ether. I remember fighting it, I was trying to make myself stay awake, you know. They put a mask over my face, and I was trying to make myself stay awake. And it was like—I can still remember it, fuzzy like—but it was like a psychological thing that this nurse—there was a nurse or either it was a female anesthesiologist, one of the two. And she said, uh, ‘The kids are all in bed, and we’re here, uh, you and I.’ You know, just a female voice. And it seemed like there was a soothing effect, and you know, the next day when I remembered that particular thing she said . . . she was talking in, like, a very seductive voice, like, uh, we were going to have relations, you know, shortly after whatever. But anyway, it just seemed like it had a soothing effect.” Charlie had invited Vanessa Sapp, a vocational nurse from Fort Worth, to play that role in his execution.

Charlie first heard of Vanessa Sapp in June 1977 when she wrote him a letter, as women of a certain type often write to condemned men. She saw him almost monthly at Ellis and once, last May, in a courtroom. He had been taken to Fort Worth for a hearing before federal district judge David O. Belew. “They told me she was there,” Charlie explained to me, “and I, uh, wanted to see her, you know. But I didn’t know what to say. So I, uh, thought it wouldn’t sound right, me being old as I am, to say that I wanted to see my girlfriend. Girlfriend! You know, that just doesn’t sound right. Well, she wasn’t my wife, so I said, I told the judge, ‘Will you let me see my fiancée?’” Judge Belew went him one step better: he offered to marry the pair. Charlie talked to Vanessa but didn’t take full advantage of the court’s hospitality.

A few days before he went to the Walls, I had my last talk with Charlie Brooks. Preliminary stories about his execution had already spilled across the front pages of the Texas newspapers. By the dozens, reporters had come to Ellis, clamoring to see him. So had a New York civil liberties lawyer, who told him to keep up hope and not to talk to media people, including me. Charlie did talk, anyway, and at quite some length. But the hope his lawyers gave him made his conversation guarded. Charlie evaded questions about his crime and his feelings and instead told me about the things he planned to do after the December 7 execution date had passed. For example, he asked me to send him clippings of the newspaper stories about him. He said he wanted to read them to a newborn granddaughter on the child’s twenty-first birthday.

In case he did become the first man to be executed by injection, Charlie had in mind a scheme to which he wanted me to be a partner. In an article about the 1960 gas chamber execution of California rapist Caryl Chessman, Charlie had come upon a trick he wanted to try. He wanted to signal me by nodding his head if he felt pain while dying. On the day of our first conversation, I had agreed to his proposal without reservations. Later, afraid that he might go on a nod, as addicts describe the behavior that sometimes follows a heroin fix, I asked to change the signal. We agreed that Charlie would shake his head, side to side, as if saying no. At all our meetings, even the last one, we renewed the pledge to stick to our deal.

The afternoon and night on which Charlie prepared to die were busy hours for the courts, boards, and individuals with clemency powers to dispense. At about 4 p.m. the state Board of Pardons and Paroles, after deliberating for hours, voted not to intervene in Charlie’s case. Some two hours later Governor Clements announced that he would not maintain the old tradition under which every condemned man was granted a single thirty-day reprieve. At about the same time, Charlie’s lawyers filed a writ with the Court of Criminal Appeals; three hours later, it was turned down. The U.S. Supreme Court concluded its deliberations in the Brooks case at about 8:30 p.m., and it, too, chose to let the execution proceed. A little before 9, federal judge Belew left his Fort Worth home for his offices downtown, where he heard a new witness for the defense, Jack Strickland, Charlie’s trial court prosecutor. Strickland told the court he had pangs of conscience about the disparity in the sentences given Brooks and Loudres. From Austin, a 29-year-old Leslie Benitez, the attorney general’s capital case specialist, cross-examined Strickland by telephone. At 10:49 Judge Belew said no to the defense lawyers but allowed them to make a new appeal to the Fifth Circuit. Calls went out to New Orleans. At 11:52 Fifth Circuit judge Alvin Rubin telephoned to say that the panel had found nothing new in Brooks’ last-minute claims. A few seconds after midnight, attorney general Mark White picked up the telephone in his office and called the Walls. He said that the execution could begin.

By about six-thirty, Charlie had finished a handwritten “Statement to the Media” begun earlier in the afternoon. Then he wrote seven letters by typewriter. Six of them were addressed to family members, the seventh to an inmate named Evans. Charlie intended his statement to be read immediately, but he wanted some of his letters to be delivered only after his death; “If you are reading this letter now,” they began. When Shabazz returned to Death Row, at about ten o’clock, Charlie gave the statement and letters to him. In the confusion and trouble of that night, Charlie’s message to the press didn’t get through; Shabazz failed to deliver it. Days afterward, he read the statement to prison Muslims and to me. Charlie’s message said, in part: “I at this very moment have absolutely no fear of what may happen to this body. My fear is for Allah, God only, Who has at this moment the only power to determine if I should live or die. . . . As a devout Muslim I am taught and believe that this material life is only for the express purpose of preparing oneself for the real life that is to come. . . . Since becoming a Muslim, I have tried to life as Allah wanted me to live.”

The message made no mention of Charlie’s role in the murder of David Gregory.

By ten the crowd outside the entrance to the Walls had grown. Early in the evening it had been composed mainly of reporters—there were about 75 of them—but as the night grew darker, partisan elements thronged in. Most were blue-jeaned students of criminal justice at Huntsville’s Sam Houston State University, policemen in training. They were in favor of capital punishment, but they weren’t wildly impassioned so much as wildly curious. Only a few carried placards, but like fish to a lantern, they all clumped up thick when the television floodlights were switched on. Vanessa Sapp, Charlie’s lover-by-letter, plowed through this crowd at about ten-thirty; his two sons and his ex-wife, at about eleven. Their arrivals set off stampedes by the men and women of the news media.

Safe within the Walls, Vanessa spoke with Chaplain Pickett, who told Charlie that she had shown up. “Is she all right?” Brooks wanted to know. Pickett said she was. “Is she strong?” Pickett nodded again. Preparations for the execution were already under way when Adrian and Derek, Charlie’s long-abandoned sons, told Shabazz that they’d like a last chance to see their dad. The minister asked Charlie if he wanted them admitted to his execution. “No, I don’t want them to see me this way,” Charlie said. Derek, Adrian, and their mother waited in the foyer, above the crowd.

At about eleven-thirty, with Pickett and Shabazz at his side, Charlie Brooks walked the few steps beyond the gray steel door into the Death Room. Without making any protest, he climbed onto a wheeled stretcher, or gurney, that had been prepared for him. Guards belted six shiny white straps around his body.

The fifteen people who would witness Charlie’s execution were assembled in the cavernous waiting room just inside the entrance to the Walls. We smoked and chatted nervously. In one pack where a half-dozen men in sports coats who looked like law enforcers. Two of these men, the local sheriff, Darrell White, and his chief deputy, Ted Pearce—who looked so much like a lawman that he had played the part of a deputy sheriff in a movie called Middle Age Crazy—wore gray Stetsons. Against the opposite wall sat Vanessa Sapp and Larry Sharrieff. Three reporters stood around the pair, asking questions and jotting down the answers. Nearby stood a wrinkle-faced man in a trench coat, Pete Cortez, owner of San Antonio’s Mi Tierra restaurant and a member of the Board of Corrections. With him was attorney Harry Whittington of Austin, another board member, wearing a charcoal pin-striped suit. Whittington slipped over to Vanessa to express his condolences for the duty the prison system was preparing to carry out. Without rancor or words, she acknowledged his message. Then she stepped out from him and the reporters, over to the window that looked onto the street below. I was standing there, watching the crowd outside.

Vanessa Sapp was dressed the best a lady of her small means and large girth could be: lustrous gray pointed shoes with gold lamé piping around the soles, two gold rings on each hand, silver earrings, and a polyester print dress.

“What are they doing out there?” she asked as she lifted a curtain aside.

“Ah, they’re demonstrating for capital punishment,” I told her, nodding toward the undulating crowd.

“In favor of it?” she snapped, letting the curtain fall back.

“Yes, they are in favor of it,” I muttered, a bit apologetic.

“Humph!” she grunted, stomping back to her seat by Sharrieff.

Larry Amin Sharrieff was poorly clad. He wore brown striped pants and a battered tan corduroy overcoat, with a high-collared blue denim shirt showing underneath. He held a huge red Koran and beneath it, pressed up against his chest, a dime store prayer rug. On his head was a crocheted white prayer cap, and on his face was a look of grave nobility. He spoke not much above a whisper when I asked him about an old friend he might have known. There was strain in his voice when, right before we were led down the corridors to the Death Room, he told me that he thought Brooks had squared accounts with Allah.

Guards in gray uniforms showed us down a darkened hallway beside a long cubicle where prisoners meet their guests on visiting days. I was at the tail end of the procession along with Vanessa Sapp, who, nodding at the guard behind her, said, “Y’all go on if you want, but I’m not walking that fast.” The truth was, she couldn’t: her emotional and bodily weight slowed her down. We were guided through a left, then a right turn, onto a courtyard bracketed by spans of Cyclone fence topped with concertina wire. At each juncture, the line stopped and waited for Sapp. At one point along the route, a man’s clean-shaven pink face peered out beneath a white towel that was draped over a small window in a door. He opened the door for us, and we shuffled past into another dark, chilly courtyard. This one was canopied with fencing material. To one side was a gray steel door with the number “2,” in red vinyl, pasted above the handle. This was the last door to open, the door to the Death Room. We filed in, and those of us who were nearest the gurney placed our hands on the black metal railing that stood between us and Charlie Brooks. All of us, I’m sure, saw him before we turned toward the railing. Most of us had already been shocked by the look on his face.

Charlie lay on a line parallel to the railing, his head craned uncomfortably over his right shoulder. His moist eyes were aimed directly at Vanessa Sapp; he had known her longer than anyone else in the room. I stood on Vanessa’s right, but I didn’t study her reaction because I couldn’t take my eyes off of Charlie. The muscles in his face were taught, his cheeks nearly flattened like those of a motorcyclist speeding into a strong, cold wind. He was scared.

The room, just twelve by sixteen feet, was too small for the troop of witnesses and too small for the event. The doctors, warden, and ministers who stood inside the railing, only inches from Charlie, may have felt that there was room enough, but the fifteen of us outside the railing could barely shift on our feet. It is a principle of architecture that the smaller the room, the greater the level of noise and tension. Everybody was skittish in that room, and though there noises, nobody heard them all. The accounts witnesses gave afterward were reminiscent of the fable about blind men examining an elephant.

Our first surprise came when we saw that an intravenous feeding tube was already in Charlie’s right arm, which was strapped to a splintlike support that jutted out from the gurney. On the ceiling above Charlie’s chest was an exhaust vent painted white, a reminder that in the days of electrocution, death gave off the foulest of fumes.

The air in Charlie’s death room was chilly but not pungent or sensuously foul. The atmosphere—that creation of our higher senses—was thick, warm, and damp with inevitability. It did not occur to me, or to several other witnesses, that the ring of a telephone call from Austin or New Orleans or Washington could have dispelled the scene around us. It was as if, on some ancient web of has-to-be, the death of bound-and-gagged David Gregory had descended on Charlie Brooks that night. There was no thought in our minds that we might speak to him, or that someone might save him, or that he could be spoken to, or saved. Charlie was set off from us, in the clutches of something more confining than straps.

At our feet were linoleum floor tiles, dishwater green, six rows of them between our railing and the spot where Charlie lay. The walls on all four sides were a glazed-brick red, lit to a dim shimmer by two broad fixtures on the white latexed ceiling. Behind Charlie, on the north wall, were three windows framed in molding of mint green. From the bottom window, curtained from inside by cotton hand towels, two intravenous lines crept out like vines. Only one of the lines reached Charlie’s arm; the other, apparently supernumerary, disappeared on the far side of the gurney. Above the window where the lines came out was a smaller opening covered with screen wire. It let sound enter the chamber on the other side of the wall—where the executioners listened. To the right of the screened window was a larger frame from which a two-way mirror stared out. When we looked into that mirror, it showed back a darkened view of the room.

Charlie’s torso was partially covered by an unbuttoned tan cotton shirt. The scars on his auburn chest and abdomen showed up as blue-black bumps and jagged lines. There was a crude jailhouse tattoo, showing a heart pierced by an arrow, on his right forearm, just below the IV’s catheter. There were other tattoos we could not see: ugly tattoos with inscriptions like “I Was Born to Die” and “Joy Pop,” a reference to the heroin kick. Charlie’s legs and the designs that festooned them—he had seventeen tattoos, all later tabulated in a coroner’s report—were covered by a pair of yellow trousers hemmed with dark thread at the ankles. On his feet were white cotton socks and blue tennis shoes. Though straps belted his body and others crisscrossed his arms, Charlie could have shifted a bit in his bonds, and later he did. But for as long as he lived before us, he was stiff with fright.

A guard closed the door through which we had entered, stopping the flow chilly air from the empty courtyard outside. After a pause, Warden Jack Pursley, a dumpy, middle-aged man on the left side of the room, spoke in a guttural but benevolent-sounding voice. “Do you have any last words?” he asked.

“Yes, I do,” the prisoner shot back, raising his head a little. Inclining it to the right one again, he returned his attention to Vanessa Sapp. “I love you,” he said in a tense but clear voice. She weaved forward a bit, blinked, and nodded.

Then Charlie chanted in Arabic from the Koran:

Ashhadu an lā ilāh illā Allāh,

Ashhadu an lā ilāh illā Allāh.

Ashhadu anna Muhammadan Rasūl Allāh,

Ashhadu anna Muhammadan Rasūl Allāh.

And then in English translation:

I bear witness that there is no God but Allah.

I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.

And again:

Inna li-Allāh,

wa-inna ilāyhi rajicūn

Verily unto Allah do we belong,

Verily unto Him do we return.

“May Allah admit you to paradise,” Sharrieff chimed from the back.

Charlie relaxed a bit, apparently content with his performance. Then he stared harder at Vanessa. “Be strong,” he said in a forceful, masculine way. She did not speak as Charlie’s surgery nurse had done, but she puckered her lips, as if to blow him a kiss.

When it was apparent that Charlie had completed his monologue, Warden Pursley, leaning on his walking cane, took a half-step forward. Loudly enough for the executioners to hear, he said: “We are ready.” It was 12:09, and those were the last words Charlie Brooks would ever hear.

Behind the north wall of the Death Room, in a warren too small for a sheep dog’s comfort, prison system administrator J.W. Estelle and others—whose names were appropriately kept secret—prepared for their task. For the first time in American penal history, men who were neither physicians nor sorcerers got ready to execute a prisoner with the forbidden tools of medicine and pharmacology. The room in which they worked was the same one where, years ago, executioners calibrated and switched the levers of electrocution. Old Sparky’s control box is still there, painted a bright blue and adorned with a brass-plated General Electric logo. On the wall adjacent to the control box sits its modern replacement, a simple, tube-steel Wilson IV stand, and beside it, a short medical cabinet painted brown. From a bag hanging on this stand a neutral saline solution had been flowing to Charlie’s arm since before the witnesses entered the room. Now the executioners filled the big hypodermic syringes with chemicals to wipe out Charlie’s life: sodium thiopental, an anesthetic and depressant; pancuronium bromide, a paralyzing agent akin to the poison used on arrow points by South American Indians; and potassium chloride, a salt that can stop the heartbeat. The executioners began to inject the poisons into the IV line.

There were tiny air bubbles in the plastic line that snaked under Charlie’s gurney and up to his right arm. You could see them percolate at the spot where the line appeared from beneath the gurney and began its slope upward. For a few seconds I watched their hollow dance of death. Then I turned my eyes back toward Charlie. He was flexing his right fist, open, then closed, open and closed. After a moment, a look of absolute, unmitigated terror took over his face, tightening its muscles more, pulling his eyelids into their folds. Tears came to his eyes but did not spill onto his cheeks. He did not whimper, or make any sound. His agony of anticipation—because the intravenous line went to the arm farthest from the executioners’ needle—was too long. It was perhaps a minute, perhaps two minutes, before he felt death creeping in. The he slowly moved his head toward the left shoulder, and back toward the right, then upward, leftward again, as if silently saying no.

I snapped to erectness. Charlie was wagging his head: was that his signal to me? Could I put faith in it? Who was sending the message, Charlie the convict or Charlie the convert? For the flash of a moment, I regretted that I had pledged to watch for signals of pain from a man who was dying of an overdose of anesthesia.

Charlie’s head stopped midway on its second turn to the left. His mouth opened and a sound came from between his parted lips. “Ahlllll . . .”

Some of the witnessed, including me, thought he was yawning. Others believed they were hearing only a loud gasp. But chaplains were nearly certain that they knew what he was doing. Earlier in the night he had told them he wanted to say three Arabic words after his monologue was done: “Allah u Akbar” (“Allah the Most Great”).

If Brooks was trying to pronounce the passwords to paradise, he never finished what he began. The groan that had started out as “Ahlllll” ended up as a long, protracted, “Uhmmmm,” and his eyes had closed by the time his lips went shut. But if Allah is the Merciful, perhaps Charlie was admitted to paradise, not as the con we knew but as Shareef, the Noble Servant he had wanted to become.

His head pointed up, his body lay flat and still for seconds. Then a harsh rasping began. His fingers trembled up and down, and the witnesses standing near his midsection say that his stomach heaved. Quiet returned, and his head turned to the right, toward the black dividing rail. A second spasm of wheezing began. It was brief. Charlie’s body moved no more.

A minute or two passed in the quick silence of that room. Chief prison physician Ralph Gray, another short, portly middle-aged man, moved to the gurney, his back toward the witness rail. He placed the sensor of a stethoscope on Charlie’s chest and moved his hands up and down Charlie’s torso, as if feeling for life. Another plainclothes physician stepped over from the left side of the room, and he, too, began feeling over the body. One of the doctors pointed a penlight into Charlie’s eyes, holding the lids back for a look. “Dilation, dilation,” I heard him say. One of them looked up toward the north wall, then walked over to the screened window. “Is the injection completed?” he asked. The reply was apparently in the negative; when the doctor returned to his station beside the gurney, I heard him say, “Well, we’ll just wait a couple of minutes.” Time without a ticking passed, and then the doctors began feeling and peering at Charlie again. After a few seconds of this, Dr. Gray straightened his posture and inclined his head, as if in a prayer. “I pronounce this man dead,” we heard him say. It was 12:16, seven minutes after the injection had begun. There was a pause and then a rustling at the back of the room. Someone said loudly, “You all will have to leave now.” We began filing out. As I came to the door, I looked over my shoulder at Charlie Brooks. His head was turned toward the rail, his eyes were half-closed. His body seemed stiff and knurled.

As we stood in the little courtyard outside, I notice that Vanessa Sapp was unsteady on her feet. Her jaws were swollen and her lips were drawn. Her eyes were sheeted with tears, but she did not sob, she did not cry. She was trying to be strong, as Charlie had wanted. I also noted that Sheriff White and Deputy Pearce had not removed their hats. The way I was raised, gentlemen take off their hats when a death is announced. I felt as though we were at a living funeral and that these men, law officers, had failed to show respect.

The lawmen in their Stetsons did not see their circumstances that way. They had not come to pay respects to Charlie Brooks or to take signals from him. Had either of them killed an outlaw during a shoot-out, he would not have removed his hat when the criminal fell. The case of Charlie Brooks, they figured, was not a whole lot different. They had come, one of them told me, “to see that justice was carried out.”

They had picked the right outlaw, too; I was one of a handful to know. After my initial conversation with Charlie, when he told me that the gun used to kill David Gregory had gone off accidentally, I read the transcripts of his trial. The testimony indicated that shortly before the shooting Charlie had threatened an employee of the New Lincoln Motel with a long-barreled revolver. Revolvers do go off on their own accord, I suppose—usually on cold days in hell. The next time our conversations turned to his crime, Charlie again proffered the excuse “and if the gun somehow accidentally discharges . . .”

“It was a revolver,” I interjected.

“I’m hip,” he said. “Yeah, I’m aware of that.”

“Revolvers don’t accidentally discharge.”

“Yeah. I’m not talking about accidentally discharge as in, let’s say, like an automatic. In order for a revolver to discharge,” he said in a self-assured way, “you have to either cock the hammer or either pull the trigger. What I’m saying is that okay, like, if you’ve got the hammer cocked, okay, it can be an accident when you twitch that finger. That don’t, that trigger can be pulled deliberately or by accident.”

Charlie Brooks, who told the courts that he was innocent, plain and simple, wanted me to know that he had put a gun in the face of David Gregory, the face of a husband and a father, that he had cocked the hammer, and that he had pulled the trigger—but didn’t mean to kill. Charlie, a convict for twenty years, didn’t believe that he was capable of malicious actions, not when he was in his right mind. “I know that I am not a cold-blooded killer,” he told me. “I know that I am not able to kill someone without compassion. I cannot identify with what happened because that was so, you know, it’s just like something you do while you’re asleep, the sleepwalkers that commit acts. They can’t feel what they would have felt had they been awake and committed a particular act.” On the evening that David Gregory died, Charlie Brooks was both stoned and soused, he said. His actions and intentions weren’t part of a whole. “I was so out of it,” he said in apology for murder, “that I can’t even identify with being there.”

Charlie Brooks was there, though, and neither the law, nor his executioners, nor common morality accepts dope and drunkenness as an excuse. But on one point I’m sure even Charlie’s executioners would agree: when taking irreversible actions, we all develop qualms about what we do.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Execution

- Death Row

- Huntsville