On a humid July afternoon, two investigators from the Texas Workforce Commission’s child labor law unit pulled into the red-dirt parking lot of Custom Cut Lumber, a sawmill located in Alto, about an hour south of Tyler in the Piney Woods. They walked onto the seventeen-acre property, strewn with milled planks, piles of sawdust, and unhewn logs, and headed toward the main building. Richard Gordon Trudeau, a stocky man with an auburn beard and a soft, raspy voice, came to greet them in the sawmill’s pine-paneled office. Samples of wooden trim hung on the wall. Card-stock religious tracts and CDs sat propped on a shelf, and affixed to the window was a photocopied Bible verse, Romans 8:24: “For we are saved by hope, but hope that is seen is not hope, for what a man seeth, why doth he yet hope for?”

Trudeau serves as an elder in the Church of Wells—an insular fundamentalist religious group that some consider a cult—and has owned the land the mill sits on since 2014. On the day of their visit, in 2018, the investigators explained to him that they had received an anonymous tip on a state hotline alleging that boys as young as 11 were working at the mill—a violation of state and federal child labor laws—and were in immediate danger. Trudeau, who was then 35, confirmed that at least four minors worked on the property but said he was unsure of the total number and exactly how old they were.

One of those boys was a gangly eleven-year-old, Trevor. (His and his parents’ names have been changed, at the family’s request, to protect their privacy.) An only child, Trevor started working at the sawmill in March 2018, according to his father. Some days, he would sort and stack wood in the scragg mill area, where short logs are hewn. After the logs were cut, Trevor and other boys would pull them off a conveyor belt, separate the good pieces from those that were misshapen or marred by knots, and stack them into neat piles. “I would do some sorting for a few minutes . . . but my main job was just stacking the wood,” he told investigators on the phone in August as they continued their inquiry, according to TWC documents obtained via a public records request.

Trevor’s family had joined the Church of Wells in August 2017, and the boy was wary of doing anything to anger others in the group, so during that phone call he did not mention one particularly unsettling experience to the investigators. One afternoon that spring, Trevor had been sorting planks when a log became jammed in the scragg mill’s power saw, causing a large blade to suddenly detach and fly through the air. “It could have cut my head off,” Trevor told me in February 2020. “Thank God it didn’t.”

The investigators interviewed the other boys who worked at the mill, levied a fine against its operators, and then dropped out of contact. For Trevor and his parents, Adam and Paula, the incident marked the beginning of the end of their time in Wells, the small town fifteen minutes south of Alto from which the church takes its name. But the tip that prompted that initial probe was just the first of several officials would investigate. In December 2021, new complaints surfaced about an underage boy working at a trim shop in Wells owned and operated by church members. Meanwhile, injuries among the mill’s adult workers eventually attracted the notice of government agencies.

In 2002 Adam, who had studied economics and culinary arts as an undergraduate in his native Peru, came to the U.S. on a work visa to cook aboard Royal Caribbean cruise ships. He soon found life at sea monotonous and transferred within the company to a position based in port. He settled into life in Miami and began attending a Hispanic Baptist church. There, in 2005, he met Paula, a Brazilian immigrant enrolled in beauty school, when she sought him out to compliment him on the turkey he had cooked for the congregation’s Thanksgiving meal. They married the following year, and that December, Trevor was born. Adam and Paula became naturalized citizens and bought a three-bedroom condo overlooking a canal in Tamarac, a northwestern suburb of Fort Lauderdale on the edge of the Everglades.

After completing a master’s degree in education, in 2013, Adam didn’t get a job in his field. Instead, he started an airport shuttle business and sold Herbalife products to support his family and pay off his student loans. One day in 2017, he reconnected with a childhood friend from Lima, who told him he had recently become part of a group of “biblical Christians” in Texas. The friend, who was visiting Miami to pick up a newly recruited family, encouraged Adam to come to Wells to see this church for himself. Adam often found that in his busy life he could not carve out time for God; he frequently opted to work the lucrative Sunday shuttle shift instead of going to church. The idea of a quieter life in Texas among a group of committed Christians appealed to him. “[My friend] started talking to me about the Church of Wells and how all the other churches are fake,” Adam said. “Somehow, he convinced me.”

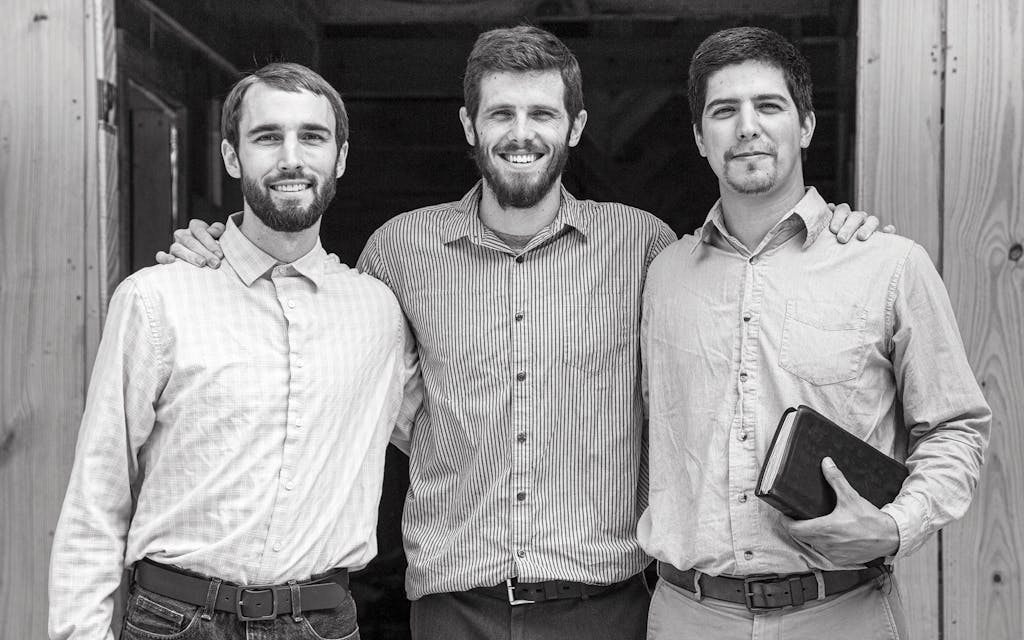

What Adam’s friend didn’t tell him was that the daily lives of the 250-plus congregants of the Church of Wells are tightly controlled by its three founders, who call themselves elders—Jacob Gardner, Sean Morris, and Ryan Ringnald. The elders have a say in everything from living arrangements to who marries whom to where and when members can travel. The group’s services are closed to outsiders, and children in the church are homeschooled. Vaccinations are prohibited. (“There are elements, fundamental elements of vaccines themselves, that are against nature, other natural laws, and other things that God’s word says,” Morris said in an October 2018 sermon. The elders did not respond to a question about their stance on vaccination.)

Congregants, who believe themselves among the only truly saved Christians in the world, view salvation as slippery—something they are at risk of losing whenever they commit what the elders consider sins, including watching television, wearing tight clothing, and practicing judo. (Social media, a recruitment tool, is allowed.) Many members are in only sporadic contact with their parents and extended families, as I reported for Texas Monthly in 2014. (Much of that contact is directed by the elders. “Brethren, Please be aware that today is *Mother’s Day*, according to the heathen, thus it would be wise to honor your mother by communicating your love,” Morris wrote in a May 2018 WhatsApp message to members.)

In July 2017, when he and his family were still living in Tamarac, Adam decided to take his friend up on his offer to visit the church. Adam, Paula, and Trevor spent a week in East Texas praying, hearing personal testimonies of salvation, and sharing communal meals with congregants. Adam was impressed by the deep faith of the “brethren,” as the members refer to one another, and marveled at their grasp of the Bible, as many were able to quote verse after verse from memory. After hearing his testimony, the elders proclaimed that Adam was saved, and seeing the appeal of life in this tight-knit community, he decided his family needed to join the church.

They drove back to Tamarac to pack their belongings into a moving truck and put their condo on the market. They returned to Wells less than a week later and bought a mobile home and a small piece of land there. “The Lord changes your plans sometimes,” Adam told me in August 2019. “He changed all my plans, and he moved us to Texas.” A month later, Morris baptized Adam in Lake Nacogdoches.

When Adam said he needed to find a job, church members told him, “No worry. We have a mill. Work there,” he recounted. Within days he was employed at Custom Cut Lumber.

The Church of Wells’s founding elders met in the mid-aughts in Waco, where Morris and Ringnald were undergraduates at Baylor University and Gardner was attending community college. The young men bonded over their shared affinity for the King James Bible and their puritanical view of an often-angry God. After Morris and Ringnald graduated, in 2008, the trio spent a couple of itinerant years preaching on street corners and colleges around the country before setting up a base in an Arlington house owned by Morris’s older brother, who had also joined the group. Bit by bit, their church grew. Those who sought to join had to first spend time “seeking the Lord,” before facing an “examination” during which the elders determined whether they were saved, a process several former congregants say involves prostrating oneself and professing to hate one’s previous sinful life.

In 2012 the group relocated to Wells, where housing was cheap, and leased the R&R Mercantile, a convenience store, gas station, and restaurant off U.S. 69, to support themselves. Richard Gordon Trudeau incorporated an entity called Charity Enterprises to run the R&R, listing nine church members, including the three founding elders and himself, as directors. Behind the store, Trudeau, who had owned a woodshop in upstate New York before joining the group, helped set up a small sawmill. In the summer of 2014, locals who were fed up with how Church of Wells members were antagonizing residents—declaring local preachers “false prophets,” telling young children they were hell-bound, and disrupting the homecoming parade—organized a boycott of the church-run businesses. The protest led Trudeau to shutter the store and relocate the mill to some land he had purchased in the nearby town of Alto.

The move, church members believe, was ordained by the Lord. In April 2019, two tornadoes tore through Alto, injuring twenty, razing more than a dozen homes, and downing thousands of trees—but inflicting no damage on the mill. “A business in the church was literally YARDS away from the destruction, but had no damage whatsoever! It is truly a blessing to be under the protective covering of Christ,” one member posted on Facebook. Trudeau stood by the town’s main intersection, holding up a placard. “Who has His way in the Whirlwind? Nahum 1:3,” the sign read. “Fear God and give Him glory!”

Today, the business, which the brethren sometimes refer to as the “Lord’s mill,” has become the main economic engine of the church. It is operated by a limited liability corporation called Custom Cut Lumber (CCL) whose manager is congregant Gregory Sean Sanders, according to filings with the office of the Texas secretary of state. Until 2021, the same mill was operated by a limited partnership called Whirlwind Lumber Productions (WLP)—which, as of 2019, was also managed by Sanders, according to a contract with the mill’s electricity provider. Eric Kolder, a lawyer for the mill, wrote that the two entities “do not have identical ownership or management” but declined to answer questions about who owned and controlled each business.

In January 2022, Kolder said the mill employed more than 10 workers but did not specify the precise total; according to TWC documents, it employed 44 people in February 2021. At least half were church members, while the rest were outsiders—drawn from Alto, Wells, and other nearby small towns. In 2020 the mill cut seven million board feet of wood, according to Trudeau. Adam, who was hired for a bookkeeping role in August 2017, told me that in recent years the mill has generated about $2 million in annual revenue and $500,000 in annual profit.

Soon after taking the job, Adam noticed what he considered to be improprieties in the mill’s finances that he said would result in trouble if the Internal Revenue Service were to conduct a thorough audit. He said sawmill funds were regularly used to buy plane tickets to ferry church members to and from international branches it had opened in Peru (the Church of Lima) and Australia (the Church of Adelaide). These tickets—sometimes for entire families with four or five young children—were written off as business expenses, and the outlays began to eat into the mill’s profits. Adam said some sawmill funds were also redirected to pay the three elders’ personal cellphone and utility bills, though none of them worked at the business. But when he raised these issues with Trudeau early on, Adam said, he was told not to worry about them. (Kolder responded to questions sent to Sanders and Trudeau and denied that sawmill funds were used to pay for plane tickets for church members or for elders’ personal expenses but said that all three men have “worked for the mill at different times in the past as independent contractors.” Gardner, Morris, and Ringnald did not respond to questions about what kind of work they did at the mill and when.)

Beyond these alleged financial improprieties, Adam was alarmed by the number of workers who would come into the sawmill office to have work-

related injuries evaluated. At least 21 injuries—including to members of the church and to workers from the broader community—have occurred at the mill since 2017, ranging from fractured toes to amputated fingertips, according to interviews and documents.

In the past five years, almost one in four known severe injuries at Texas sawmills has occurred at the single mill operated by Church of Wells members.

Many mill employees who are not church members are vulnerable because of their criminal history, education level, or poverty. Some former employees told me their wages were paid under the table, without deductions for federal income and payroll taxes, though Kolder denied that WLP or CCL ever paid workers off the books. All of this made these employees less likely to report their injuries or pursue legal action. Under Texas law, employers are not required to carry workers’ compensation insurance, but without such coverage a company can be sued by employees who are injured at work. CCL first obtained a workers’ compensation policy on January 21, 2021, according to the Texas Department of Insurance. That policy ended after one year, and as of press time, the mill does not have coverage. Kolder wrote that the company is in the process of reapplying for workers’ compensation insurance after the person who handled the matter at CCL died last year.

Some injured workers were given raises and light duties while they recovered, according to interviews with multiple men injured at the mill. Others weren’t given much—as Adam learned when he slipped on sawdust on the office stairs and tore a ligament in his knee in October 2018. When he asked for help paying for his surgery, Trudeau and Sanders declined, though they eventually covered half the cost of his MRI, Adam said. (Kolder told me that, to his clients’ recollection, Adam opted to use his own “good private insurance” to cover his medical bills. Adam said he did not have insurance at the time.)

In his kitchen, in Lufkin, in February 2020, Adam explained Trudeau and Sanders’s rationale: “They said, ‘We’re not paying because it was the judgment of the Lord. There must be some sin in your life . . . or the Lord would not allow it to happen.’ ” Adam initially internalized this way of thinking. “Praise God for His blessed chastisements,” he wrote in an October 2018 WhatsApp message to church members about his knee.

When he started at the mill, Adam would marvel at how adeptly one lean eleven-year-old laborer handled the tools that hung from his leather belt. “I was born in a rich family in Peru,” Adam told me. “My father trained my head and not my hands.” He said he wanted his son Trevor to learn those other skills too. And so, in March 2018, Trevor joined the boys at the mill, earning $8 an hour added to his father’s paycheck. Trevor worked a four-hour shift two mornings a week.

Paula was alarmed and later claimed, in a document filed in a family court proceeding, that Trevor had been “forced as an 11 year old boy to work in a dangerous sawmill.” She worried too that her son’s education was being neglected. Instead of attending school full-time, Trevor, after his morning shifts, received homeschool lessons in two-hour stints in a small shed next to the sawmill kitchen. Patricia Scofield, a church member who had trained as a teacher before joining the group, taught him from Christian workbooks that Adam purchased.

Once the TWC investigators showed up, Trevor and the other boys stopped coming to the mill. Randall Valdez, who ran operations at the time, penned a letter to the investigators that August to defend the mill’s actions. “We, as Christians, desire that our sons will both have a good education and the ability to work with us. This is primarily to help them become men,” Valdez wrote. “Our practice is to keep them away from jobs that would be considered hazardous in accordance with what I understood to be the law.”

But the investigators determined that many of the tasks the boys performed were hazardous. They fed wood into the machines and removed freshly cut planks from the conveyor belts. One of the eleven-year-olds told investigators that he ran the saw while the men were on break and sometimes operated the forklift. (Federal regulations expressly bar anyone younger than eighteen from operating power-driven woodworking machines or forklifts.) In one photo, taken in July 2018 before the investigators came, Trevor—wearing ear protection, gloves, and safety goggles—uses a “bark spud,” a long tool with a sharp blade, to scrape bark off a log. Another eleven-year-old without any protective equipment can be seen working alongside him. Both boys wear red Custom Cut Lumber shirts.

When he mentioned that he might pursue legal action against the mill, he was told by a supervisor that the injury was “God’s wrath, so it wouldn’t hold up in court.”

The state’s child labor investigators ultimately found that three minor boys—Trevor, the other eleven-year-old, and one thirteen-year-old—had been placed at a “great level of risk” through their work at the mill, in violation of the section of the Texas Labor Code that prohibits employing children younger than fourteen for most jobs. They also found that a seventeen-year-old had been employed at the mill, in violation of federal and state regulations that bar minors age sixteen or seventeen from work in certain hazardous occupations, including logging and sawmill operations. Using an “administrative penalty assessment” worksheet, which weighs various factors including the seriousness of the violation, and determining that the mill’s operators were not aware of the law, the investigators levied a $1,233 fine in January 2019. (Under state law, they could have levied penalties as large as $10,000 per violation.) The mill paid the fine at the end of the month. Kolder confirmed that payment, adding that WLP “complied with the caseworker’s recommendation.” CCL “operates in strict compliance with state and federal” child labor laws, he wrote.

Adam told me he had not been aware that Trevor working at the mill violated child labor laws and described feeling “uncomfortable” upon learning this from the investigators. “I never wanted to break the law,” he told me. Yet he maintains that the work experience benefited his son. “It was really good for [Trevor] and the other kids. Of course it was dangerous. But they started seeing the importance of work,” he told me. “[Trevor] learned a lot of things that when he was in Florida he never did.”

In March 2022, the TWC fined another business run by church members for a child labor violation involving one of the boys named in the 2018 investigation. In a series of videos captured by a concerned Wells resident, that boy, who is now sixteen, can be seen outside Custom Cut Millwork, an interior trim shop located in the former R&R Mercantile building. According to TWC records, the business is owned by Moses David, the father-in-law of elder Sean Morris. (Kolder said the trim shop is operated by a separate company. The shop’s address was listed on CCL’s website in January 2022 but was removed after Kolder was asked about it.) In the videos, the boy stands on a wood kiln, loading planks onto a waiting forklift and adjusting a lever on the machine when the man driving appears to have trouble operating it. In other parts of the footage, he acts more like the child he is, swinging playfully on the tines of the forklift.

After interviewing the boy and learning he had used an air-powered nail gun and engaged the parking brake of the forklift, a TWC investigator found that the trim shop employed him in violation of two provisions of federal child labor law and fined the business $170. David did not respond to questions about the investigation. Ronnie Saltsman, a church member who is the manager of Custom Cut Millwork, sent a letter to the TWC acknowledging the violation and apologizing for it. “It is now our policy that minors are not allowed to work here ever,” Saltsman wrote.

The problems at Custom Cut Lumber extend beyond child labor violations. Multiple workers who have been employed on the property told me that the equipment is operated without proper machine guards and that lockout-tagout procedures—safety protocols that ensure equipment is shut down and rendered inoperable during maintenance—are not regularly followed. (Kolder disputed these allegations, writing that the company works with a workplace-safety consultant to “ensure compliance with all [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] safety standards, including Lockout and Tagout Systems.” He did not respond to a question asking him to identify the consultant.) New hires, some former employees say, start work without receiving any formal safety training. The congregants who run the mill “basically say they put safety in God’s hands,” said Chris Payne, a Wells resident who worked at CCL from 2018 to 2019 but does not belong to the church.

Gregory Sean Sanders, the church member who now manages the facility, is keenly aware of the dangers at the mill. On September 6, 2017, he was servicing a machine that had not been locked out. Another worker, who didn’t notice that a repair was underway, turned on the machine. Sanders’s hand caught in a pulley, resulting in a compound fracture to his left arm that required surgery, including the insertion of plates and screws. “Blood squirted everywhere,” one eyewitness told me. “He was lying on the ground holding his arm, praising God for the correction.” (Members of the Church of Wells believe that God “chastens” or “corrects” those he loves.) Sanders did not respond to a question about whether he was hospitalized as a result of this injury.

Even after Sanders’s accident, lockout procedures weren’t regularly implemented, five workers told me. In August 2018, Troy Dannenberger, a church member who works at the mill, wrote in a WhatsApp chat for employees, “[W]e need training on lockout, tagout. A machine should never be able to be turned on that someone is working on. It’s is suppose [sic] to be locked out.” (Kolder did not respond to a question on whether lockout-tagout training was conducted at the mill following Sanders’s injury.)

Even a well-run sawmill presents myriad hazards. OSHA does not mince words on its website: “Working in a sawmill is one of the most dangerous occupations in the United States.” But the rate of injury at CCL exceeds that of the industry at large.

OSHA regulations require employers with more than ten employees on their payroll—hourly, part-time, seasonal, and temporary workers included—to track all workplace injuries and illnesses that need medical treatment beyond first aid in an “OSHA 300” log. This log must be retained for five years and must be presented to an employee or federal inspector upon request.

Church members fell to their knees and started praying. “I said, ‘I believe in Jesus and s—, but you need to take me to the hospital,’ ” Poole recounted.

Kolder said that Whirlwind Lumber Productions was not required to keep an OSHA 300 log because the company never had more than 10 employees. But in August 2018, a TWC child labor investigator recorded that the sawmill had 22 employees. In April 2020, WLP certified that the company had 21 employees when it applied for and received a $84,492 loan through the federal Paycheck Protection Program. And a review of an internal WhatsApp chat group titled “Sawmill Hours Turn in” spanning late 2017 to early 2019 showed that, on average, 15 church members worked at the mill each week for hourly pay. (Kolder did not respond to specific questions about the number of employees named in each of these documents, writing only that WLP used a “combination” of partners, employees, and contractors to run the mill.)

In the absence of those logs, a variety of government documents, medical

records, and interviews conducted with eighteen mill workers reveal that no fewer than 21 injuries—including at least 5 severe ones—have occurred at the sawmill since 2017. OSHA’s severe-injury reporting requirements state that all employers under its jurisdiction must report amputations, eye losses, and work-related hospitalizations to the agency within 24 hours. Between January 2017 and August 2021, thirteen Texas sawmills reported a total of 19 severe injuries to OSHA, according to an analysis of agency data. Two of those reported injuries came from CCL, representing 10.5 percent of the statewide total. That figure jumps to 23 percent when the 3 unreported injuries are folded in. This means that in the past five years, almost 1 in 4 known severe injuries at Texas sawmills has occurred at the mill operated by Church of Wells members.

One metric OSHA uses to evaluate an employer’s safety record is the incidence rate of nonfatal injuries and illnesses, which measures the number of recordable incidents per worker hour. Texas Monthly confirmed two workplace injuries at the sawmill in 2017, six in 2018, four in 2019, and four in 2020. Assuming that in each of those years the mill had 22 full-time employees working fifty weeks—as TWC records indicate it did in 2018—that rate would exceed the industry average every year and in 2018 would be nearly five times as great. (“2018 was four years ago. The mill’s operations have improved since then in many ways, including safety,” Kolder wrote in an email.) In 2021 the sawmill had 44 employees, according to TWC documents, and five injuries; the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics does not yet have data for 2021 on the incidence rate industry wide.

When asked about how the mill’s injury rate compares with that of other sawmills, Kolder responded, “CCL does not have data regarding the injury rate of the industry at large, but it firmly believes that its accident rate is below industry averages.” He said it is “patently false” that there have been an unusual number of accidents at the mill and that the mill “had many more than forty-four thousand worked hours in 2018,” which would make TM’s injury rate calculation “way off.” But he declined to provide the number of worked hours at the mill. To get an incidence rate below the industry’s 2018 average, workers at the mill would need to have clocked nearly 200,000 hours for the year, or the equivalent of 99 people working 40 hours a week, fifty weeks a year.

Two former OSHA officials reviewed a spreadsheet of the injuries that TM confirmed occurred at CCL in the past five years and said that given the type of injuries and their frequency, the company seemed to lack an effective safety program. Kathleen Fagan, a physician who specializes in occupational medicine and spent ten years as a medical officer for the agency in Washington, D.C., before retiring in 2019, told me that the injuries listed would be considered recordable by OSHA and noted that eight of them resulted from lack of proper lockout-tagout procedures. “So, for a small company, these are terrible statistics,” she wrote. “This is a dangerous workplace with no apparent safety program or effort to evaluate their injuries and take steps to prevent future injuries.”

When accidents occur, workers told me, victims are usually first triaged on-site by Mark de Rouville, a sawmill supervisor and church member who is a former Navy SEAL with training as a medic. If workers’ injuries are too serious for de Rouville to handle alone, he or another supervisor will drive them to an urgent care center or emergency room for licensed medical treatment. One worker, Jyran Shaw, a former Alto High School track star, told me that a two-by-four jammed in a trim saw and flew into his forehead in September 2020, when he was 23, leaving him with a gash above his eyebrow and a concussion. He said de Rouville, who was not at the mill, tried to persuade him over FaceTime to let him staple his forehead closed. (“It’ll just leave a more visible scar than stitches would,” de Rouville said, according to Shaw. De Rouville did not respond to a request for comment.)

Kolder told Texas Monthly, “CCL cares for its workers; if there is ever an injury, it is very important to make sure first aid is administered, and also make sure they have a ride to medical facilities if needed.” Some workers told me, though, that after their injuries they were pressured to return to work immediately. In the fall of 2018, said Myles Robinson, who was then 25, his arm was bumped into an unguarded moving part of the scragg mill by another worker, fracturing several bones in his right hand. He said his supervisor told him he would lose his job if he missed work. He returned the next day in a cast. Robinson recounted in a January 2022 interview that when he mentioned that he might pursue legal action against the mill, he was told by a supervisor that the injury was “God’s wrath, so it wouldn’t hold up in court.”

Three severe injuries that were never reported to OSHA stand out. In 2018 an unguarded circular blade sliced through three fingers of a 29-year-old worker, John Michael Armstrong. His pinkie was cut down to the second knuckle, and he lost much of his index finger after two surgeries to try to save it. In July 2019, a man from San Augustine, a town about an hour east of Alto, nicked the tip of his right middle finger down to the bone on a saw. To treat the injury, a doctor had to slice off the end of the man’s finger, meeting OSHA’s definition of a “medical amputation.”

And in the summer of 2018, eighteen-year-old Alto resident Raymond Poole was maimed as he tried to clear a jammed piece of wood from the conveyor belt of a machine that turns logs into pallet cants. No one stopped the machine so that Poole could tackle the jam safely, as OSHA regulations require. His left hand got caught and sucked under the belt. He fell back and shrieked in pain, but, he said, no one could hear him over the roar of the machine, so his injury escaped notice until he threw a rock at a coworker standing nearby. Once church members at the workstation realized he was injured, they fell to their knees and started praying, he said. “I said, ‘I believe in Jesus and s—, but you need to take me to the hospital,’ ” Poole recounted. A mill supervisor took him to a hospital in Jacksonville, some thirty minutes north, where he spent four nights and had surgery to place a rod and screws in his left wrist.

Poole had been working at the mill for a year at the time of the incident. He’d started there as a seventeen-year-old who was paid under the table and performed work that is illegal for minors to do, such as operating saws. “In Alto, the mill is the only place you can make a quick buck,” he told me in December 2021. (“My client does not recall Raymond’s age when he started providing services for [WLP],” Kolder wrote.)

Poole said that a few days after he left the hospital, Sanders shared with him that he too had badly broken his arm at the mill. “He said, ‘I know what it feels like,’ ” Poole recounted. He upped Poole’s pay $2, to $10.50 an hour, and gave him light duty answering phones, sweeping the kitchen, and supervising other workers for the next two months. When his uncles would suggest that he sue over his injuries, Poole would reply that he was being treated well. But three years later, he regrets not filing a lawsuit within the statute of limitations. He has a broad scar on his wrist, he can’t lift anything heavy with that hand, and his fingertips often go numb. His arm throbs when the weather changes. “They f—ed up my life. I got to live with this for the rest of my life,” he told me.

When asked whether the mill reported these three severe injuries to OSHA, Kolder replied that the three men were independent contractors, so the company was not required to record their injuries for the agency. But the affected workers were paid by the hour, were essential to the sawmill’s operation, worked using the business’s saws and other machinery, and were directed and supervised by mill management. “This seems clearly to be a case where the government needs to investigate whether these workers were misclassified as independent contractors,” said Debbie Berkowitz, a former chief of staff at OSHA who is currently a fellow at Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. “The company clearly is in a very dangerous industry. In order to hide their true injury rates from the government, it seems to me they have a great incentive to start labeling these workers as independent contractors. They do this so they can outsource their responsibility to provide safe conditions to employees.” she added, “From what I’ve found, the only reason to avoid scrutiny is because you have unsafe conditions you don’t want to fix.”

It wasn’t until January 2021 that CCL managers first reported an injury to OSHA, according to agency records. The afternoon after a twenty-year-old Crockett man caught his right thumb in the pulley of a chop saw, fractured it, and was hospitalized overnight, a mill employee contacted the agency, admitting that the saw’s belts and pulleys did not have guards, which are required.

The elders would isolate him to preach at him for hours at a time, sometimes to have “the demons cast out of him.”

Two months later, Sanders visited OSHA’s website to report that a 24-year-old employee had been hospitalized after a blade sliced into three fingers, triggering the first-ever federal inspection of the mill. According to a record obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request, a compliance safety and health officer from the agency spent thirty minutes at CCL on the afternoon of March 23, 2021, and conducted a partial inspection, examining the five-head trim saw that had mangled the worker’s hand and any “plain view” hazards, in accordance with agency rules. Employees told him the saw jammed “multiple times a day,” and the inspector found that it was not properly guarded. He initially fined the mill $9,557, an amount later reduced to $5,734.20 after Sanders signed a settlement agreement with the agency. The mill later remedied the hazard by attaching a caution sign on a yellow chain warning employees not to walk past that point while the machine is running. (Kolder wrote that OSHA found only “one safety issue” in its inspection.)

R. Dean Wingo, a 38-year veteran of OSHA who last served as the assistant regional administrator for Region Six, which includes Texas, reviewed the report and noted that an inspector spending only thirty minutes at the business amounted to “a very cursory review.” He said a full inspection should have been conducted examining every piece of machinery. Fagan, the former OSHA medical officer, also said the agency should return to thoroughly examine the business.

On April 5, after a version of this story was published online, OSHA agents returned to CCL to conduct additional inspections. Details of those, including whether new violations were found, are not yet publicly available. If the agency did find another violation, it could bring bigger fines: the maximum penalty for “willful or repeated” violations is $145,027 per incident.

The church may be seeking to get out of the sawmill business, however. In April 2021, with lumber prices near a record high and sawmills throughout the country operating at capacity, Trudeau put the mill up for sale on Facebook Marketplace for $6.5 million, a marked jump from the $120,000 value assessed for property-tax purposes. Asked in a Facebook comment on the listing about the reason for the sale, Sanders replied, “We are selling because we are wanting to go to the next stage of our lives. The business is booming and very profitable. But has taken much time and investment. We believe the Lord has other things ahead for us.”

When the state stopped Trevor from working at the mill, his mother’s concerns about her new life did not abate. Paula was unhappy about how belonging to the church was changing Trevor and shrinking his world. “He is fearful to talk, play, see or listen to anything that is not part of the Church of Wells cult,” Paula wrote in a January 2019 court filing. The elders would isolate him to preach at him for hours at a time, sometimes to have “the demons cast out of him.” Trevor told me that these one-on-one sessions placed him under extreme stress. “I really wanted out of the church when the elders were yelling on top of me like that,” he said.

Paula found her new environment personally stifling too, bristling at the level of control church members exerted over her. She had been a hairdresser in Florida, but the Church of Wells’s elders pressure married women to forgo work outside the home, so she became both “dependent on” and “dominated by” her husband, according to the court filing. She spent her days studying the Bible, attending extended prayer meetings, and cooking lunch for the men and boys who worked at the mill. The other women policed how often she called her mother, telling her that her mom was “becoming an idol” in her life. “The sisters ask me, ‘You talk to your mother today?’ ‘You talk to your mother this week?’ ” Paula told me in an August 2019 interview. They also discouraged her from outward

expressions of joy. “One day I was happy and singing,” Paula recounted. The wives chastised her, insisting, “You need to be sober. You’re too light.”

One summer day, Paula drove to Lufkin to browse a religious bookstore. There, she met and befriended the wife of a pastor of a small Hispanic Baptist church in town. Soon she started attending services at that church in secret. She began making plans to leave the Church of Wells with her son, confiding to some friends in Wells who weren’t members. They helped her secure a small RV where she could stay in Lufkin, and on a Wednesday night in early October, she and Trevor left Wells. When Church of Wells members learned of their departure, they sent dozens of messages to their group’s main WhatsApp channel praying for her swift return. The next afternoon, Adam located Paula at the Lufkin mall by tracking her cellphone location using an app.

The Lord, Adam said, used the Church of Wells—the cult, as he now calls it—to pull him out of his sinful life in Florida.

Adam begged Paula to return, but she would not budge, so he took Trevor back to Wells without her. “I plead with her many times to come back, but she says she wants to work, have her money, live here in Lufkin. Let’s keep praying dear brothers. The Lord can turn her heart towards Him and me again,” he wrote in a WhatsApp message to church members that day. Later that month, he wrote the members that Paula was “starting to love the world again” and thinking “evil thoughts against the church and brethren.”

Meanwhile, in Lufkin, Paula found a lawyer and filed suit in family court, seeking to gain primary custody of her son and to bar Adam from “taking the child around any member of the Church of Wells” and from “speaking to the child about the Church of Wells.” In the courtroom, prior to the hearing, Paula’s lawyer approached Adam, who was representing himself, and Church of Wells preacher Jordan Fraker, who had accompanied him. The lawyer told Adam that Paula loved him and didn’t seek a divorce; she wanted only to leave the church and for Trevor to go to a real school. He said she would happily drop her case if they could work toward that goal. Fraker insisted that Adam not agree to this, advising him to forget his wife, forget his family, and follow Jesus. That command jarred Adam as it sank in, and he instantly decided to defy Fraker and agree to the custody terms Paula had proposed.

That February, Adam, who was still living in Wells, accepted an invitation from Paula to attend a service at her new church in Lufkin. When the Church of Wells elders learned of this, they viewed it as a betrayal. Elder Jake Gardner texted Adam to cast him out of the church, sending the same message to a church WhatsApp group: “Beloved brethren, I am very sad to say that our brother [Adam] is fallen from his first love and his godly, fearing confessions of his restoration, and beyond this even, he is congregating with another man’s church in Lufkin who has been harboring his apostate wife and son! This is truly abominable wickedness how he has chosen to repay the Lord for his kindness! Thus and thus he is no longer worthy to behold or be among the holy Passover feast that we are holding by faith, and without leaven!”

Recently, I asked Adam to reflect on his time at the mill. He is now living in Lufkin with Paula, who cuts hair at a salon in town, and Trevor, who plays for his high school’s tennis team. Adam told me he has found his calling in serving, for a small stipend, as the assistant pastor of the same small Lufkin church his wife once attended without his knowledge. He believes he wouldn’t have gotten there without the time at the sawmill. The Lord, Adam said, used the Church of Wells—the cult, as he now calls it—to pull him out of his sinful life in Florida and into this new one ministering to others. “God, in his mercy, took me [to Wells],” he said, “and put me through fire.”

Sonia Smith is a writer living in Dallas.

This article appeared in the June 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Trouble at the ‘Lord’s Mill.’ ” An abbreviated version originally published online on March 28, 2022. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy