It’s been another hot year in Texas. Back in May, before the year was even half over, the Austin-American Statesman made the call that 2017 would be the hottest year on record for the state. According to records from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Texas had an unusually warm winter, which gave way to above-average temperatures so far this summer.

Hot summers are nothing new in the Lone Star State, of course. And when it’s hot outside, most Texans dial down the thermostat to keep cool indoors. A recently published study in Science has some bad news about that: in the years to come, it will only get more expensive to crank up the air conditioner or keep your fridge (with those ice-cold drinks) running.

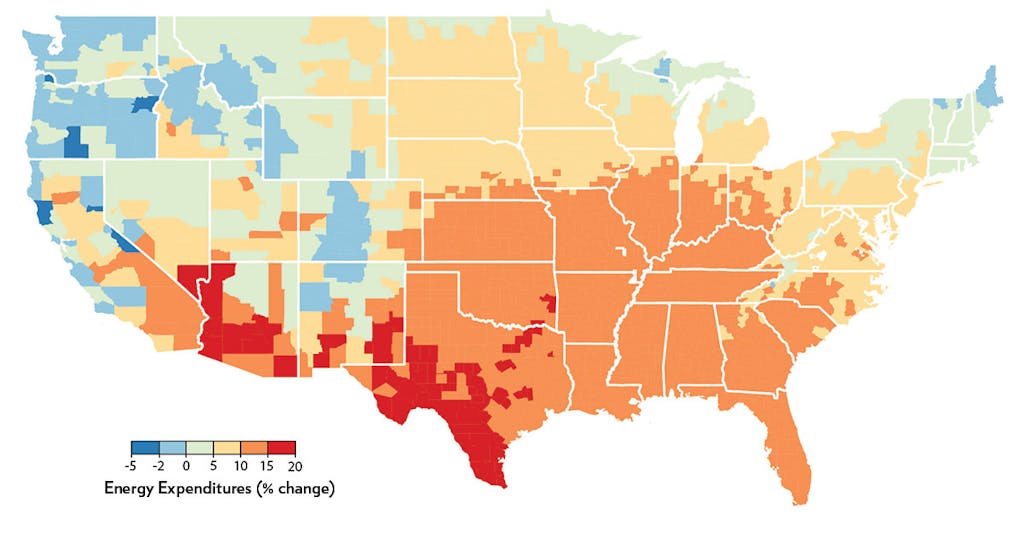

Researchers found that energy costs across the state could increase by as much as 20 percent as the effects of climate change from greenhouse gas emissions take hold. The study maps the direct economic impacts of climate change across the United States, county by county, in categories such as energy expenditures, crime rates, labor productivity, and health impacts.

“The overarching idea behind the paper was to pin down the impacts of climate change to people at really local scales,” says Amir Jina, a postdoctoral scholar and senior fellow at the University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute who worked on the study.

Texas is particularly susceptible to the damaging effects of climate change on its economy and society, Jina explains, because it’s already hotter than most of the United States. “There are different [temperature] thresholds for when these things become very damaging, and places in the southern United States are already close to those thresholds.”

Every degree matters when it comes to the impacts of climate change.

Climate scientists predict that the average global temperature is already on track to increase by between two and four degrees Celsius (three and seven degrees Fahrenheit) during this century.

To put that into perspective, NASA estimates that the difference between a degree and a half of warming and two degrees is the difference between heat waves that last up to three times longer.

And as temperatures climb higher globally, energy demand, including here in Texas, will rise alongside it.

“It’s the classic challenge of climate change,” Jina says. “There’s no doubt that the amount of energy that is consumed will have to increase. That’s a fact of life, and air-conditioning makes large parts of Texas livable for parts of the year. The more energy we use from fossil fuels, the more we accelerate the process of warming.”

The problem of affordable energy isn’t a problem of the distant future for Carol Biedryzcki, the executive director of Texas Ratepayers’ Organization to Save Energy, but rather a problem of right now (and the recent past as well). She remembers 1998 as a significant date: it was one of the hottest years on record at the time (it’s been beat out by nearly every year in the twenty-first century). That year, 1998, Biedrzycki petitioned the state’s Public Utility Commission to suspend utility companies’ ability to disconnect power to households that had fallen behind on electric bill payments.

At ROSE, Biedryzcki helps low-income residents find ways to keep their utility bills affordable, whether that’s through subsidies or energy-efficiency programs that reduce overall electricity usage.

“It’s getting hotter all the time, and people have more trouble paying their bills,” she says. “A lot of times people say, ‘Oh, you can get by without air-conditioning.’ That’s not really true. You might be able to live without it, but you can’t live a normal life without it. You can’t lead a healthy life without it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s essential.”

As I’m talking to the Biedryzcki on the phone, I can’t help but notice, a bit guiltily, that the office I’m sitting in is set to a chilly 74 degrees Fahrenheit, nearly thirty degrees colder than the stifling temperatures outside.

“According to the Texas Department of Health, if you don’t have air-conditioning and the heat index is over 100, you need to go to an air-conditioned facility,” she tells me. “My concern is that this increasing trend of super hot weather that we seem to be experiencing over the summer, means that people are using more electricity, and they’re using it at a time when it’s most expensive.”

The cost of running an AC unit all day, or even all night, can add up quickly. According to a 2016 report from the Energy Institute at the University of Texas, over 20 percent of households in the state of Texas are “energy burdened,” meaning that they spend nearly a tenth of their income on energy bills.

For a family living at or below the federal poverty line of $24,600 a year, ten percent of an annual income is a lot of money. And Biedryzcki says she’s helped families surviving on just $700 a month in the Austin area. “We need to be preparing for a future where people will need more help in order to stay in their homes and pay their bills,” she says. “A mere fraction of the people who need utility assistance actually receive it. The need is much greater than the available funds,” Biedryzcki says.

Simple fixes, such as updating old AC units and furnaces, insulating windows and weatherizing homes, can cut energy costs in half. But these are often too expensive for residents who can’t afford to pay bills in the first place.

In fiscal year 2016, the total funding for Texas’s Comprehensive Energy Assistance Program amounted to just over $106 million, according to data provided by the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs. The budget allowed the department to serve 136,000 households. There were over 652,000 households in the state with incomes 50 percent below the poverty level in the state that year.

Increasing state and local funding for utility assistance programs could help level the playing field, but Biedryzcki laughs at first when I ask her why this isn’t a priority. “They don’t see it as profitable,” she says bluntly. “We need more of a commitment from our state and local governments to make housing more affordable with an appropriate emphasis on utility bills.”

Energy costs might not be on the top of the policy priority list this legislative session, but Jina says that the purpose of the study which he worked on was to give local lawmakers information and data which they could use to shape such policies in the future.

“We can show where the damage is—it’s up to the policy makers to make sure that people aren’t completely [spending money] out of pocket as they’re spending more on energy. It’s really places like Texas that will be at the forefront of this, because Texas is very wealthy as a state,” says Jina.

“It’s got a well-functioning political system by and large, compared to countries that will be badly hit in sub-Saharan Africa or somewhere else. The opportunity is enormous, as well as the challenge.”

- More About:

- Energy