This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

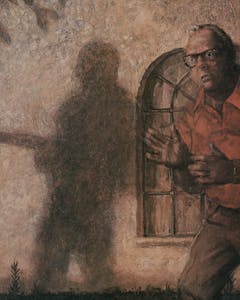

South of the Nueces River lies a strange and opaque Texas. Nature designed it as part of Mexico, and for a time so did man; the Nueces, not the Rio Grande, was the border under Mexican sovereignty. To cross the Nueces is to enter a land that does not easily yield its secrets. Drive through any other part of Texas, and you can see at once how the land is being used: farming, ranching, timber speculation, rural settlement, oil. In South Texas nothing is obvious. There is only the brush, mesquite and catclaw and huisache, that closes over the land like a ground fog. A few feet above it, from the top of a rise, one can see everything—but one can see nothing. The brush obscures roads, houses, cattle, pump jacks, everything but the horizon and the ocean of brush. South Texas is a land of not two but three cultures, Anglo and Mexican and hybrid, where a man can thrive only if he understands the imperatives of all three. This is a land of high fences and locked gates and few roads, where a man can disappear when he wants to and reemerge when he wants to. This is a land of empires, a land where the few have always dominated the many, a land where a man can live by rules that apply nowhere else. A man like Clinton Manges.

“That’s the ball game,” said Clinton Manges as the football spun toward the ground, its journey through the goalposts complete. Even though the San Antonio Gunslingers, Manges’ franchise in the United States Football League, had just clinched an all-too-rare victory, his tone was analytical rather than celebratory. If there is anything Clinton Manges’ life demonstrates it is that his time is better spent planning for the next battle than savoring the last victory. He had watched the first half of the game from the sideline, the bald spot in the middle of his hair exposed to the sun that was shining with one-hundred-degree ferocity. Although the Gunslingers scored three times, Manges spent the entire time engrossed in conversation, seldom looking at the field and never unfolding his arms for so much as a single clap.

The San Antonio Gunslingers are the most visible element of one of Texas’ least visible empires. Clinton Manges owns more than 150,000 acres deep in the South Texas brush country, but his most important holdings are beyond the capacity of man to see: mineral rights in the depths of the earth and fealties in the souls of Texas politicians. His mystique and money have combined to make him the most powerful—and most controversial—behind-the-scenes figure in current Texas politics.

No one else has so much influence. The attorney general, Jim Mattox, comes to hunt at Manges’ ranch. So does the land commissioner, Garry Mauro. The comptroller, Bob Bullock, is an old friend who last year allowed his official license plates to bedeck Manges’ car.

No one else is so brazen about acquiring that influence. In 1982 Manges spent more than $1 million on political contributions, much of which went to candidates for offices directly concerned with the fate of his empire. It is no accident that the ascendancy of Clinton Manges has paralleled the ascendancy of the liberal wing of the Texas Democratic party. Manges has helped fund that rise with large contributions to Mattox, Mauro, Bullock, agriculture commissioner Jim Hightower, and assorted judges and legislators.

No one else has benefited so much from influence. Last year the Texas Supreme Court took Manges’ side in a long-running dispute with the Guerra family of Starr County—and the decisive vote was cast by a newly elected justice who had received more than $100,000 in contributions from a group funded almost entirely by Manges. That might have been a record for the most money ever contributed to a Texas Supreme Court candidate by a litigant, except that twice as much Manges money went to another candidate, who lost.

The Lessons of South Texas

Clinton Manges rose to power by applying the teachings of three mentors who had mastered this strange and opaque land.

No one else has chosen such ambitious targets for his influence. Recently Manges took on the third-largest company in America, suing Mobil Oil for $1 billion in a highly publicized lawsuit. Early this year, after the intervention of Jim Mattox forced Mobil to bargain with Manges, the giant oil company relinquished its lease on 64,000 acres of Manges’ land.

But it is more than influence that makes Clinton Manges important. It is the kind of man who has this influence. This is a man who, when questioned by a lawyer about why he wanted a particular property interest, answered, “Why do you want your car?” (think, now, why do you want your car?) and then continued, “Because, by God, it’s an asset.” This is a man who has achieved power and influence despite compiling a dossier that would make pariahs of others. Here is why Clinton Manges belongs in a black hat:

He is a convicted felon.

He has corrupted a judge.

He has manipulated two banks.

He has resisted paying his taxes.

He has resisted paying his bills.

He has resisted repaying his loans.

He has resisted paying his lawyers.

He has written hot checks to the state.

He has feuded with friends and business associates.

There are places where a past of that sort isn’t a barrier to political power (Louisiana comes to mind), but before Clinton Manges, Texas wasn’t one of them.

At halftime of the Gunslingers’ game Manges moved upstairs to the owner’s box, an unadorned section of the press level with two rows of folding wooden seats. On this Sunday afternoon, the day after the Democratic primary, the Manges box had the look of a political boiler room—and, lacking air conditioning, the temperature as well. Manges stood near a door in the back, greeting local politicos as they came and went: a school board member, a state senator, a campaign strategist, and others of that ilk. Finally he plunked down on the steps at the end of the first row to watch the climax of the game. He wore what is practically his uniform: beltless slacks and a white polo shirt, with “Gunslingers” emblazoned on the right and “Clinton Manges” in a crescent above it. (On non-game days he favors Countess Mara polo shirts, which have the initials “CM” prominently displayed.) The deep creases of a man who has known too much dirt, wind, and hard times surrounded his eyes. Except for the gold jewelry—a Rolex watch, a bracelet, a horseshoe ring studded with diamonds—he seemed to suggest a pit bulldog, a compact but formidable creature who hunkered rather than sat, with muscular forearms and, as his conversation made clear, the instinct to fight and the instinct to survive.

He talked about one of his favorite subjects, the Texas establishment, which he regards as his archenemy and which, he believes, regards him likewise because of contributions to candidates it doesn’t own. In his mind the establishment is the reason for his black-hat image. “Every big bank has a big law firm sitting in it and a portfolio full of oil company stocks,” he said bitterly. “That’s why there’s all this controversy about me.”

A sudden outburst of cheering interrupted him. Improbably, the Gunslingers had scored a last-second touchdown to win by a larger margin than expected. The team on the field had taken on the personality of their owner. They are anathema to the San Antonio establishment, which fought Manges’ stadium expansion because of noise and pollution. The Gunslingers aren’t very good at winning in the traditional ways. But like Clinton Manges, they are experts at beating the odds. In their first eleven games, they exceeded the expectations of the odds-makers nine times.

The noise subsided for the last time. “The oil companies take seven eighths of a man’s oil and give him ten thousand dollars bonus,” Manges went on. “They’re just stealing his oil. They had control of the courts. The landowner didn’t have the money to fight and hold out in the courts. They have just raped this country.”

Clinton Manges was one landowner who did have the money. But he has won his influence as much with his rhetoric as with money. Relaxing with their host after a day of hunting at Manges’ ranch, his guests are likely to hear him inveigh against the oil companies, banks, insurance companies, and big law firms that are the underpinnings of the old Texas establishment. “I’m going to bring them all down,” he has vowed before such gatherings, as he recounts how the establishment has kept ordinary people from getting a fair hearing in the Legislature and a fair trial in the courts. It sells, too. Mattox says of Manges’ view of Texas political history, “That is the gospel, and it’s the absolute truth.”

Lloyed Bentsen, Sr.

The Art of the Land Trader

He taught the young Clinton Manges the fundamental rule of survival in South Texas: land is power.

Who is this man of mystery? The answer to that question lies not in Austin with the politicians or in San Antonio with the Gunslingers but in the brush country, because Clinton Manges is most of all a man of his place. Like the South Texas land itself, he does not yield his secrets easily. He operates in a region bounded by the Nueces on the north, the Valley cities on the south, the King Ranch on the east, and Dolph Briscoe’s ranch on the west, an emptiness as big as New Jersey but without a daily newspaper or a town of five thousand people or anything that passes for historical record. The story of Clinton Manges is concealed deep inside the file drawers and legal tomes of courthouses in towns far from the beaten path: Hebbronville, Zapata, San Diego, Raymondville, Rio Grande City. There, in hundreds of long-forgotten lawsuits and old property transactions, the real Clinton Manges can be discovered, the quintessential South Texas figure whose mentors were the great figures of South Texas. There was Lloyd Bentsen, the real Lloyd Bentsen, not the U.S. senator but the senator’s father, the preeminent land promoter in a region built by land promoters, who taught Clinton Manges the lessons of the land dealer’s trade. There was George Parr, the political strongman of Duval County for four decades, the notorious Duke of Duval, who taught Clinton Manges the lessons of the political boss’s trade. And finally, there was Oscar Wyatt, the head of the Coastal Corporation, the dark genius of the South Texas oil and gas game, who taught Clinton Manges the lessons of the oilman’s trade. The story of Clinton Manges is to a great extent their legacy—the result of what a man can do when he masters the lessons of South Texas.

George Parr

The Art of the Political Boss

Under the Duke of Duval, everything was politics, politics was everything, and anyone not for him was against him.

The watershed moment of Clinton Manges’ life occurred during his late twenties, on a day when he was managing a service station in the Valley and Lloyd Bentsen stopped in for gas. At that time Manges must have been one of the least likely candidates in all of Texas for the position of power broker. His heritage was Okie, straight out of Steinbeck. Born in Cement, Oklahoma, in 1923, one of seven children, he became a nomad child of the Great Depression. As soon as he was old enough to pick cotton efficiently, he dropped out of school; his formal education did not extend beyond the elementary grades. His family moved south to Junction, where his grandfather renovated mattresses; young Clinton rode with him from ranch to ranch to pick up old bedding. He moved again, south to Port Aransas and then farther south to Raymondville, a moody and unfortunate farming town situated too far north of the Valley to have tourists and too far south of the great ranches to have oil. The end of World War II found him sweeping out the movie theater in Raymondville. But he had a way of winning people over. He married the daughter of a prosperous Raymondville farmer, and he had a knack for getting people to loan him money—not banks but townsfolk, who helped him get started in his chosen career, watch repair. He was too restless to stay with such sedentary work, and when Lloyd Bentsen drove up, Manges was still looking for his life’s calling.

While working on Bentsen’s car, Manges asked where his customer was headed. Up the road to see Farmer Jones, who had some land for sale, said Bentsen. Manges nodded, then disappeared into the building. When he emerged, he told Bentsen that he could save him a trip. He had just called Farmer Jones and bought an option on the land. Mr. Bentsen could deal with him right there.

In that one inspired moment, Clinton Manges’ life changed forever. His bravado had earned the respect and, it turned out, the financial backing of Lloyd Bentsen, then and now the leading citizen of the lower Valley. After their service station encounter, Manges began taking land deals to Bentsen, buying and selling property for his principal while Bentsen remained in the background. Manges could not have picked a better mentor. Still active today (at ninety, Bentsen farms 42,000 acres, runs cattle, works on land deals, and just bought a small railroad line), he is regarded as the premier land trader in the history of Hidalgo County. That’s saying something, because Hidalgo County has been the scene of some of the great land promotions in Texas history. Among the county’s patron saints is a silver-tongued land trader who took groups of potential buyers into the country and said, as part of his spiel, “Why, this dirt is so good, it’s good enough to eat,” which he would then proceed to do—and before long, those in the audience would reach down and sample a little dirt themselves. The prevailing ethos is best reflected by the name of the main street in the county seat, Edinburg, which honors a county official who was so enmeshed in land schemes that he was finally removed from office for corruption.

The Bentsen brothers, Lloyd and Elmer, were hardly free of controversy themselves. They were taken to court by disgruntled buyers who contended that their new citrus groves came without sufficient water for irrigation. And then there were mineral rights—or rather, there weren’t mineral rights, not if you bought from the Bentsens. Just last fall a story was making the rounds in Hidalgo County about a local doctor who was treating a patient for indigestion. The doctor felt the patient’s stomach and said, “I think I’m going to find the biggest gas play in Hidalgo County right here.” “If you do,” said the patient, “Lloyd Bentsen will own the mineral rights.”

Clinton Manges learned from Lloyd Bentsen the fundamental lesson of South Texas: land is power. Their most ambitious deal, a South Texas classic, began in 1954 when Manges and another man from Raymondville bought the 16,000-acre La Coma ranch in northern Hidalgo County with $950,000 in cash from Bentsen and set about marketing it with the unwitting help of the federal government. The federal Soil Bank program provided funds for owners of small tracts who would let their land lie fallow. La Coma, of course, was a large tract. So Manges sold off the land in pieces small enough to qualify for Soil Bank money (less than 700 acres) and told buyers that they could use government dollars to make the early payments on the land. It worked so well for La Coma that Manges and Bentsen duplicated the deal on another 7,000 acres. Alas, someone blew the whistle and the Department of Agriculture stopped the Soil Bank money. When some of the buyers couldn’t make the payments, Manges reacquired the land through foreclosures for $100. Some of the buyers were eventually successful in getting their money released by the Department of Agriculture, but by that time the land belonged to the Bentsens.

Manges was learning more and more about how South Texas worked. The La Coma deal demonstrated that the road to wealth often runs through the public treasury; Manges would invoke that wisdom on numerous occasions throughout his career. Another lesson came out of La Coma, one that shaped Manges’ hostile attitude toward oil companies and thus came to have a major impact on Texas politics years later. La Coma had once been part of the King Ranch. It was lopped off in a settlement, but that happened after the ranch leased its mineral rights to Humble Oil (now Exxon), so when Manges bought it, the King Ranch lease was still in effect. In 1960 Manges paid a visit to Humble and produced the deed to La Coma. He asserted that Humble had failed to live up to its obligation to develop his property and questioned the validity of the lease—the biggest and most lucrative oil and gas lease in Texas. The episode was a dress rehearsal for the battles Manges would wage two decades later against Mobil, Texaco, Sun, and other companies that, he would argue, had not properly developed his holdings. Humble, rather than risk a court test of its precious lease, paid up. Manges got $176,000 for his mineral rights and to extinguish his claim. But when the deed was turned over to Humble, it came from Lloyd Bentsen, the real owner of the property. Manges had learned that the relationship between oil company and landowner is that of predator and prey and that it is better to be the former than the latter.

Oscar Wyatt

The Art of the Oil and Gas Baron

The lesson of Wyatt’s wheeling and dealing was to do the deal now and take care of the consequences with another deal.

Manges was a natural at the business of land trading. He had an uncanny instinct for assessing the value of raw land. Despite his lack of education, he had no peer when it came to understanding the intricacies of deals. He knew how to read people; he could be charming and expansive and incredibly persuasive, or, as with Humble, he could be belligerent and ruthless. That was the great advantage to Lloyd Bentsen of having a man like Manges around; when the time came to play rough, Bentsen could remain above it all, always the great man of the Valley.

Manges worked long, long hours, not only trading property but also operating a cotton gin and a bowling alley in Raymondville. They both bore the name “Mongoose,” which Manges once described as less a play on his name than a reflection of his admiration for a tough animal that likes to kill snakes. He learned to get along on two or three hours of sleep, something he still does, and to do business at any hour of the day or night. (Years later, a lawyer Manges had taken to Las Vegas on a pleasure trip was startled when Manges notified him of a business meeting that was to convene at 3 a.m.)

After the Humble triumph, however, things began to turn sour for Manges. Rains soaked the cotton fields at harvest time, and Manges, who had speculated by buying cotton on the stalk, watched helplessly as the plants withered and his investment collapsed. His commissions from land trading (20 per cent in some of the Soil Bank deals) weren’t enough to expiate the disaster. It was time to apply one of the South Texas lessons. Manges proposed that the City of Raymondville buy his bowling alley for $500,000, which he promised to use to bring industry to town. This time the road to wealth did not run through the public treasury, mainly because the mayor cast the deciding vote, against him. Never one to give up without a fight, Manges challenged the mayor in the upcoming 1961 election. The mayor took out a full-page ad in the local paper headlined DO YOU WANT THE CITY OF RAYMONDVILLE TO PAY $500,000 FOR A $250,000 BOWLING ALLEY? and asked pointedly about one pro-Manges official, “Who bought the shiny new Cadillac he is driving?” With the local establishment lined up against him, Manges lost the election by a margin of more than two to one.

The summer of 1961 saw the beginning of what was to become a familiar pattern for Manges. He wrote hot checks, failed to pay numerous bills, and eventually was sued for unpaid debts and taxes. The Small Business Administration, which had advanced Manges the money to get into ginning, foreclosed; it not only sold his equipment but also discovered that he had made a false statement in his loan application, which was a criminal offense. In 1963 Manges was indicted. By that time he was out of the bowling alley business as well. In 1965 he pleaded guilty and paid a $2500 fine. The man who would become an intimate of judges and a crony of the Texas attorney general was now a convicted felon.

Never again would Clinton Manges squander his energies on running a business. He had learned the hard way that in South Texas, where there is no industry and most of the commerce is agricultural, the only real wealth lies in the land—its sale, its acquisition, its hidden riches. Saved from bankruptcy by Lloyd Bentsen’s aid, Manges held on to a few property interests and resumed land trading. He and his family (he has four adopted children) left Raymondville for San Antonio, but in effect Manges lived out of his car as he crisscrossed the southern half of Texas, doing deals as far east as Corpus Christi and as far west as the Permian Basin. In the late sixties he put hundreds of thousands of miles on his cars, driving at breakneck speed. (He was once reported to have collected 21 speeding tickets between 1969 and 1974, and he sometimes hired young drivers, giving them the instructions “Don’t let it get under ninety.”) In the cluttered back seat he carried his guns, including his pride and joy, an elaborately tooled .257 Weatherby, the flashiest, most expensive rifle money can buy.

He picked up a new backer, a respected McAllen investor named Vannie Cook. Although the two men couldn’t have been more different—Cook was a Valley aristocrat, a man of inherited wealth who enjoyed the fruits of his deals more than the deals themselves—the team clicked because having Manges enabled Cook, like Bentsen before him, to remain deep in the background. But while Bentsen had kept Manges under tight rein, remaining the dominant figure, Cook was less assertive. They never committed their own agreements to writing. Manges bought, Cook paid, and they settled later, usually by swapping property.

His long years spent doing deals for others had a lot to do with the making of the combative, relentless adversary that Clinton Manges is today. He was under none of the social constraints that might have inhibited a Lloyd Bentsen or a Vannie Cook. He had no public image to protect, no peers to answer to, no membership in the establishment to keep current. Bentsen and Cook couldn’t afford to step on toes; Manges couldn’t afford not to. Sometimes he’d work on a deal in which his cut depended on how mean and tough he could be. Such a deal was his purchase, with Cook’s backing, of the huge McElroy ranch in the Permian Basin in 1965.

The ranch covered more than 80,000 acres of thinly vegetated land south of Odessa. Manges bought just the surface of the ranch; the minerals already belonged to Gulf, whose orange pump jacks lined the highway for ten miles on either side of the road leading into Crane. (It is said that when old man McElroy signed the lease with Gulf, he had the company send his bonus money to the ranch in an armored car just so he could see it before it went to the bank.) The pump jacks aren’t all that sit atop the land, though. Gulf’s pipelines are clearly visible, parallel to the fence lines. So are giant concrete slabs that Gulf has abandoned at old rig sites.

Soon after buying the land, Manges sent out ranch hands with notebooks to record in detail how Gulf’s operations had damaged the land. The damage was part of his deal: Manges knew that Gulf’s lease contained a provision requiring the company to bury its pipelines (an enormously expensive undertaking) if the surface owner demanded it. Manges demanded it. This was straight out of South Texas. He was the predator, the oil company his prey. He didn’t really want the pipelines buried, of course; he wanted Gulf to pay for the privilege of leaving them on the surface. But Gulf refused to be bluffed, and when Manges filed suit, he found out why Gulf would not pay. The company produced a document signed by a previous surface owner giving the company the right to keep the pipelines on top of the land. Manges lost the fight and sold his interest in the land to Cook, but the experience wasn’t wasted. Once again Manges had shown his grasp of the lessons of South Texas, and although he has lost this time, the day was coming when he would win.

But Manges’ luck was about to change. In 1971, using $2 million advanced by Cook, Manges bought the Guerra ranch in remote Starr and Jim Hogg counties, south of Duval. It was a dream deal, one that every land trader in South Texas knew was there to be made—Lloyd Bentsen, Jr., among others, had tried and failed—but it took Clinton Manges to pull it off.

The Guerras had been one of the ruling families of South Texas. They traced their Valley lineage back to before there was a Texas, to 1767. Manuel Guerra was the boss of Starr County before World War I; his son, Horace, inherited the mantle and ruled until after World War II. Horace’s legacy was a South Texas aphorism (“Never trust a gringo carrying a Bible or a Mexican smoking a cigar”) and a partnership arrangement for his six children that was supposed to protect the family’s holdings from inheritance taxes and land traders like Clinton Manges.

But things fell apart in the third generation. The five brothers and a sister didn’t get along. Paralyzed by jealousies over who would be the new boss and who had the right to borrow how much from the family partnership, the Guerras had lost most of their political power. They had generous check-writing privileges against the partnership account at the family-owned bank in Rio Grande City, but some abused it more than others and were deep in debt to the partnership. The rivalry among them was so severe that the siblings couldn’t even agree on terms for leasing the jointly owned 72,000 acres for oil and gas development. While the South Texas gas play went on around them, the Guerra lands remained virgin, waiting for someone who could get everybody together, make a deal, and win the right to act for the family.

The Guerra deal keeps popping up at various stages of Manges’ life, and for good reason. Sixteen years after Manges first got involved, it is still lingering in the courts, some aspects of it unresolved. But there is another reason that the Guerra deal has played such a large role in Clinton Manges’ career. In its many twists and turns it illustrates most of the elements that make him such a controversial and fascinating figure. On the one hand is his craft: his ability to put a deal together, to use his holdings to the maximum advantage, to fend off challenge after challenge to his authority and remain in control. The Guerra deal changed Clinton Manges from an agent into a principal and provided him with the means to build an empire. On the other hand is his craftiness: cozying up to neutral officials, falling out with his benefactors, seizing every advantage for himself at the expense of others, and playing hardball with those who are at his mercy.

Manges brought off the deal not by bringing the Guerras together but by dividing them even more. In 1968 he proposed to buy the land, half the Guerras’ mineral rights, and the right to lease the property for oil and gas. By persuading two of the brothers, Joe and Virgil, each to transfer his one-sixth interest in the partnership to him, Manges was able to go to court to ask for the appointment of an impartial referee, known as a receiver. So far, so good. Manges was certainly entitled to a receiver to break the deadlock, and although the anti-Manges Guerras appealed the appointment, they lost. But then strange things began to happen, the kinds of things that seem to happen in South Texas.

While the receivership question was still on appeal, Joe and Virgil struck again. Claiming the right to act for all the partners, they gave Manges what he wanted: a deed to the entire 72,000 acres and to half the minerals. The other Guerras were distressed that the court had not stopped the wheeling and dealing while the case was under its control. And it didn’t assuage their fears that the judge, C. Woodrow Laughlin of Alice, bore the taint of having been previously removed from office by the Texas Supreme Court. (His first official action upon taking the bench in 1953 had been to dismiss a grand jury that he suspected was about to indict his brother. Under the law then in force, Laughlin could run for his old job in the next election.) The receiver Laughlin appointed turned out to be a buddy of Manges’, Jim Bates of Edinburg, who was then a state senator. When Bates married in 1970, during the receivership, Manges gave his bride a new Pontiac. While the status of the Guerra property was still very much in doubt, Bates served as a director of the First State Bank in Rio Grande City, which Manges had acquired as part of his dealing with Joe Guerra.

One by one, the remaining Guerras gave up the fight and ratified Manges’ deed to the ranch, in exchange for individual settlements. But that wasn’t the end of the strange happenings. Early in 1971 Bates recommended that Manges get his deed—free and clear, with no liens—although the Guerras claimed that Manges still owed them money. Bates’ explanation was that Manges owed nothing “at that time”; later, however, Manges paid the Guerras more than $200,000. By that time, though, Bates’ lien-free deed had enabled Manges to mortgage the property at the Bank of the Southwest in Houston, providing millions just when he was maneuvering to buy the Duval County Ranch and the Groos National Bank in San Antonio. Shortly after the loan, Manges, who had paid around $54 an acre for the Guerra land, sold 2900 acres, without minerals, to a rancher for $5 an acre. The rancher later testified that his son had handled Manges’ loan at the Bank of the Southwest.

The first Guerra case was finally put to rest in 1974. But new disputes over the mineral rights flared up almost immediately. To date the people who have profited the most from the whole affair are the lawyers; the Guerra deal has spawned more than twenty lawsuits in nine counties. The Guerras didn’t do so well. The promise of royalties Manges held out back in 1968 has yet to be realized, and four of the brothers never will realize it, because they died before the litigation did.

Vannie Cook, Manges’ partner, didn’t fare so well either. Cook and Manges had their usual handshake deal: when Manges won control of the Guerra properties, Cook would have the right to buy half of the lands and minerals. But, Cook later testified, he realized very early in the deal that Manges was looking for a way to shut him out of any of the minerals. Their dispute, like the Guerras’, lingered in the courts for years, not being resolved until 1982. Instead of half of Manges’ 50 per cent mineral interest, Cook settled for only 6 per cent. For the first time, but not the last, Manges had fallen out with a partner. He lost a backer, of course, but after the Guerra deal, he didn’t need Vannie Cook anymore. He had assets of his own, and soon he had the Duval County Ranch.

Right Man, Right Place

West of Alice the topography changes abruptly. The flatness of the coastal plain contorts into a bumpy unevenness that is more than rolling, less than hilly. At the Duval County line, ten miles to the west, the black dirt of the cotton fields yields to sand, rocks, thorns, and brush. This is rough, isolated country, and as one travels west, it becomes rougher and more isolated. Freer, two thirds of the way across the county, is the most remote town in South Texas. To the west, Laredo is more than an hour away through the brush. Eight miles down the Laredo Highway, on the left, is a metal arch that marks the entry to the Duval County Ranch. Across the arch, red letters spell out “C-L-I-N-T-O-N M-A-N-G-E-S,” with the M in an open heart shape. Down below, guards maintain a vigil from an outpost just behind the entrance.

The ranch covers 100,000 acres, most of them in the shape of a north-south rectangle 14 miles long and 8 miles across. A large burl off the middle of the western side supplies the remaining acreage. As Texas spreads go, the Duval County Ranch is big but not great. It has none of the grand tradition of the XIT or the 6666 or the King Ranch. It was founded not as a nineteenth-century range empire but as a twentieth-century investment syndicate by speculators from Houston and New Orleans. Oil, not cattle, was their object when they put the ranch together in 1919. The country was too rugged for the usual cow-and-calf type of operation; in that era South Texas ranching consisted of dumping steers in the brushland, letting them run loose, and trying to find them several years later. The ranch’s absentee managers in Houston leased the land for grazing and waited for the oil boom.

The ranch’s owners had no intention of going into the oil business for themselves. Instead they planned to lease the mineral rights—the right to explore for and produce oil and gas. The ranch’s share, known as the royalty interest, would be one eighth of every barrel of oil produced, converted to money. In the twenties the investors signed a series of oil and gas leases, the largest of which was the 64,000-acre lease with Mobil that Clinton would one day challenge. But the land was no more hospitable for oil than it was for ranching. Roads into the brush were almost nonexistent. There was no water for steam power, so drilling crews used mules. Surveyors cleared sight lines by machete; operators cleared well sites with axes rather than bulldozers. Not until the thirties did the oil start coming out of the earth—just in time too, because by then the ranch was in serious financial trouble. Oil saved the ranch (actually, it saved only the southern pastures; another 44,000 acres were lost in a settlement after the ranch couldn’t pay off a loan from Humble), and for forty years the oil flowed and the investors prospered.

In the mid-sixties factions began to develop among the owners. A group of shareholders suspected that the ranch managers were about to buy up enough stock to secure a majority. The remaining owners, headed by a New Orleans lawyer, had no ambitions to run the ranch themselves, but neither did they want to lose voting control or the option of selling out. To protect the value of their holdings, they combined their stock into one bloc. That made it easy for an outsider to buy control of the ranch in a single deal. And around 1970 that’s exactly what an outsider named Manges set out to do.

When he first heard about the trouble at the Duval County Ranch, Manges must have found it familiar. It was like the battle he was then waging for the Guerra ranch. There was dissension, factions, bosses without solid control. What’s more, the circumstances were ripe for a sale. The owners no longer had to hold on to their stock to enjoy the royalties. In 1960 the ranch company’s board of directors, tired of watching double taxation eat up their royalties (taxed once as income to the corporation, once as dividends), permanently spun off 80 per cent of the royalties to the shareholders. The company’s main source of income was gone. Many of the shareholders lived far from South Texas, had never seen the ranch, did not share management’s enthusiasm for investing the company’s remaining income in Houston real estate, and because of the spin-off had no financial incentive to remain owners. All Manges had to do was come up with the right price. The ranch managers argued in vain that it was too soon to sell, that in time the real estate would pay off as the oil had. They were right, but their resistance was futile.

Manges found the right price—a little over $5 million, or $2500 a share. This time he needed no benefactor; with the help of two institutional loans the money, and the ranch, were all his. Of course, he wasn’t getting much in the way of mineral rights, just the remaining 20 per cent of the royalties, but there would be time to resolve that later. For the moment what mattered was that he had a power base at last. It was the ideal match of the right man and the right place. Clinton Manges and Duval County had found each other.

The Duke of Duval

Duval County is probably the best-known county in Texas. Its name has been synonymous with political corruption for more than seventy years, ever since Archie Parr consolidated the power that he eventually passed to his son, George, who held it until his death in 1975. The mystique of Duval is heightened by its isolation. It looks entirely southward; no road enters San Diego, the county seat, from the north. Ironically, the incident that earned George Parr his greatest notoriety—the late returns from Box 13 that elected Lyndon Johnson to the U.S. Senate by 87 votes in 1948, earning him the sobriquet “Landslide Lyndon”—did not occur in Duval County at all. It actually happened next door, in Jim Wells County. (Appropriately, the first building on the Duval side of the line is the courthouse, a clear announcement that those who pass are entering another domain.)

The Parrs rarely had to resort to stealing elections. For the most part they produced voting majorities that would have made Richard Daley envious. The Mexicano underclass, its poll taxes paid by the Parrs, provided the votes, and the Parrs provided for the Mexicano underclass. The Parrs ran Duval County the way Robin Hood ran Sherwood Forest. As public officials, they took from the rich—the oil companies and the absentee landowners—through high taxes; as political bosses, they tapped the public treasury to give to the poor. Whenever a Mexicano family needed a little extra money—for a wedding, a funeral, an illness—el patrón was there with a handout. The support the Parrs received on election day was won not by intimidation but by friendship, and the affinity of the Mexicanos for the Parrs went all the way back to the time when Archie was the only Anglo in the county who deigned to learn Spanish. Of course, while the Parrs were dipping into the treasury, they managed to keep something for themselves. Once George bought a 55,000-acre ranch with county funds; on another occasion he used a county loan to solve one of his frequent problems with the IRS.

As a new arrival in Duval County, Clinton Manges knew he had to get on the good side of the Parrs. He had a head start; he and George Parr had hunted together and run quarter horses together, but that wasn’t the same as politicking together. Manges took out a little insurance. Adverse money was the only political enemy George Parr feared. The Parrs knew how to deal with reformers (one tactic was to cut off the water to their opponents), and they knew how to deal with investigators (the current Duval County courthouse replaced one that had burned immediately after the Texas Supreme Court ordered an audit of county books). But George never got over losing an early battle with the Klebergs about a highway they blocked that was to run through the King Ranch. Parr blamed his defeat on their wealth, and for the rest of his life he would refer to that loss and tell his friends, “You’ve got to go with the money.” Soon after Manges took over the Duval County Ranch, he loaned Parr’s nephew $100,000, and although a few people cautioned Parr about getting too close to Manges, his answer was, “You’ve got to go with the money.”

Manges quickly reaped the rewards of being on the inside. The county lowered the taxes on the Duval County Ranch—not that it made any difference, since the ranch didn’t pay up anyway. In 1974, at Parr’s direction and with the full complicity of an officer of Manges’ ranch, the tax assessor issued a fraudulent document certifying that all the ranch’s property taxes had been paid, when in fact they had not.

Manges had become part of a society structured from top to bottom according to the ways of South Texas. Some were already familiar to him: the use of public funds for private purposes (one of the celebrated symbols of Duval County for years was the fire hydrant in the yard of Parr’s Spanish-style home, with a hose permanently attached to bring public water to Parr’s pecan trees) and the treatment of the oil company as the enemy (the Parrs even kept Freer, the Anglo oil town, from having its own school district; they used tax money from the oil fields to run the poor Mexican schools on the other side of the county).

In Duval County the political lessons mattered most of all. There was only one lesson, really: everything is politics, and politics is everything. In South Texas it could not be otherwise, for two reasons. First, ethnic undercurrents raised the stakes; behind every election was the eternal issue of which culture would survive. That’s why men have died over politics in South Texas, lots of men. Second, for many in the brush country, politics was the only hope for improving their lot in life. The oil business was out; those jobs were filled from outside. Only land and government were left. Either a person labored on a ranch or a farm all of his days or he helped deliver the vote to the Parrs and could then aspire to a job in the courthouse or the school district. Politics was the way off the land.

The pervasiveness of politics created its own logic. In a political system that depended on loyalty, loyalty had to be rewarded—and disloyalty punished. In the mid-seventies a number of Duval County teachers lost their jobs because of votes they had cast years before. Because so much hinged on politics, there was no tolerance of fence sitters. In George Parr’s Duval County, anyone who wasn’t known to be for him was presumed to be against him. Finally, just in case some reformer got ideas, Parr recognized that the most important official was the district judge—not just because of his rulings, but especially because of his control of the grand jury, which decided whether an activity was criminal. When a judge hostile to the Parrs took office in the late forties, George Parr backed his own candidate—none other than the same C. Woodrow Laughlin who, years later, presided over the dispute between Clinton Manges and the Guerras.

For a time in the early and middle seventies, there were newspaper reports that Manges aspired to become the next Duke of Duval. But that was not his destiny. He had none of the patrón in him. Other Parr insiders noticed that while Parr always spoke in “we’s,” Manges always spoke in “I’s.” Parr craved power more than property and liked to say, “I don’t have anything but a bunch of friends.” Manges craved assets. The two men shared a contempt for the establishment that ran the rest of Texas, the oil companies that took riches out of the earth they didn’t own and the politicians who didn’t understand South Texas, but otherwise they were as different in their own way as Vannie Cook and Manges had been. What Manges got from Parr was not his legacy but his lessons. Those lessons explain a lot about the person Clinton Manges is today, because a man who has lived by them can never again think of government as a neutral force.

At War With Big Oil

Two weeks after taking full control of the ranch in early 1972, Manges showed up at Mobil’s South Texas headquarters in Corpus Christi. “You’re raping my land,” he began, and the conversation went downhill from there. Manges complained vituperatively about pollution of the surface from saltwater leaks associated with oil production. He had a point. The former owners had been so desperate to encourage drilling that they made all sorts of concessions to oil companies operating on the ranch. The companies had been allowed to dispose of salt water on the surface instead of digging pits to contain it. They had also been excused from burying pipelines. Much of the damage was thirty years old and more. The old ranch company hadn’t really cared; it was an absentee owner and its concern was oil. Clinton Manges, though, was a resident owner and his concern was money. The oil wasn’t doing him much good—the spin-off to the previous shareholders remained in effect, so the ranch’s interest in the minerals was just 20 per cent, or about $200,000 a year at the pre-OPEC oil price. Manges demanded that Mobil compensate him for the surface damage. And, he reminded Mobil, he had the right to require the company to bury its pipelines. Unlike Gulf at the McElroy ranch, Mobil had no document handy to get out of the predicament. Mobil decided to deal.

That April Manges and Mobil reached a settlement. Mobil paid Manges $415,000 for pollution damages and $5000 for the right to keep its pipelines on the surface. Manges took the $420,000 and paid it right back to Mobil for 107 producing wells located on the ranch. The wells were marginal, and many of them were about to be plugged or temporarily abandoned, but for Manges that wasn’t the point. As a neophyte rancher, he had taken on one of the most powerful companies in the world and won.

If Mobil thought that the settlement would satisfy Manges, it was quickly disillusioned. At the very least Manges wanted to renegotiate the leases made by the old ranch company. At the most he hoped to drive the oil companies—at least half a dozen majors and even more independents—off the Duval County Ranch and reclaim their mineral rights for himself.

Either way Manges had a lot to gain. The spin-off that had transferred the royalties to the owners of the old ranch applied only to the old leases. If the leases terminated, so did the spin-off. The old owners would be left out in the cold; Manges would inherit their 80 per cent and his income would increase fivefold. Manges tried to get Mobil to take a new lease. But Mobil knew that it would be risking a lawsuit for defrauding the old owners and refused. Later Manges tried the same tactics with an Exxon lease on the ranch. Same result.

That left the alternative of driving the companies off altogether. Here was the chance for big money. An operative oil and gas lease contains two things of value. One is the working interest—the portion of each barrel of oil (seven eighths, under the Mobil lease) that belongs to the oil company. The other is acreage. The Mobil lease tied up all 64,000 acres, even though its wells were on only a small portion of the land. No one else could operate on the leased property without Mobil’s blessing, which could only be acquired for a price. But if the companies lost their leases, Manges would have both the working interest in the existing wells and the right to lease out (or develop for himself) the remaining acreage.

The difference in dollars is staggering. The current price of oil is about $30 a barrel. Under the Mobil lease Manges received 52 cents a barrel: the one-eighth royalty, less another 30 per cent that Exxon owned as a result of its Depression-era foreclosure, less the old owners’ 80 per cent spin-off of the remainder. If he could break the leases and operate the property himself, Manges would have everything except Exxon’s share of the minerals, or $21 a barrel.

So Clinton Manges declared war on the oil companies. He had already settled with Mobil, which had by far the biggest lease on the ranch. Then he went after the little fish—the independents operating on the ranch. He sued them for pollution. He wanted more than money this time. He wanted the leases forfeited. Moreover, he asked for an injunction not just against pollution but against all production. Such a sweeping remedy was beyond the reach of most courts, but Clinton Manges was in Duval County.

Thanks to a master stratagem by George Parr, Duval County had a hometown judge. The sparsely populated brush country counties where Parr ruled didn’t generate enough litigation to justify having their own judge—traditionally they had been part of a judicial territory that included Alice—but in the late sixties Duval County filed a flurry of delinquent tax suits to provide a statistical justification for a new court. The Legislature went along with the game and created a court for Duval, Jim Hogg, and Starr counties, which together had fewer than 50,000 people. Parr also got his judge, O. P. Carrillo, a member of an old Duval County clan.

What was true for Parr had also become true for Manges: the most important official was the local judge. Carrillo would be presiding over the pollution suit. He would also be taking over the Guerra case, since the property no longer fell within Judge Laughlin’s jurisdiction. What followed was not exactly subtle. Manges wrote a $6915 check to a San Antonio auto dealer to help pay for Carrillo’s new Cadillac. He gave Carrillo stock in, and directorship at, and unsecured loans from the bank in Rio Grande City that Manges had acquired as part of the Guerra deal. He gave Carrillo an eat-now-pay-later grazing lease. Eventually these and other dealings would cause Carrillo to be disqualified from the Guerra case (although he refused to withdraw voluntarily), and they would play a part in his subsequent impeachment by the Legislature and his removal by the Texas Supreme Court in 1976.

But all of that was unforeseen. In 1973 Carrillo gave Manges an injunction in the pollution case, preventing the independents—even some oilmen on nearby land that Manges didn’t have a claim to—from operating their wells. Manges offered to buy the oilmen out for salvage value, making it plain that he intended a long siege and even telling one operator who was well into his sixties, “You’re not going to live long enough to see the end of this.” One of the operators took Manges up on his offer; the rest, including the sexagenarian, fought on. The offending oil wells were shut down for 32 months before an appellate court, calling Carrillo’s injunction an abuse of judicial discretion, allowed them to resume production.

Meanwhile Manges imposed restrictions that increased the cost of operating on the ranch for producers not targeted in the pollution suit. In late 1972 he closed a number of highway gates leading to the oil wells, forcing many operators to drive miles out of their way to go through designated entrances. In 1973 he assessed a $2500 fee for each new well drilled, to cover damages to the surface. In theory, both actions could have been overturned in court—but the court was O. P. Carrillo’s. Again, some small operators acceded to Manges’ demands.

But the big boys could afford to fight. When Manges locked the gates, they broke the locks with bolt cutters. When he demanded his royalty in oil rather than money, they found language in the lease that allowed them to refuse. And when, despite the previous settlement with Mobil, he asked for another $1 million for sick cattle he said the company had harmed by pollution, Mobil bypassed O. P. Carrillo and went to federal court. After a lengthy legal struggle, Mobil got an injunction against further interference with its lease. Texaco did the same after Manges’ ranch company refused to allow drilling unless Texaco resurfaced a ranch road or built a new one.

By the mid-seventies Manges had reached a stalemate. In time he would renew the war on the oil companies, and once again his first target would be Mobil. For the moment, however, he began to exploit his gains from the first round of combat. Clinton Manges, the scourge of the oil companies, mobilized all of his resources and invaded the oil business.

A Deal With Oscar Wyatt

A ranch hand who later worked for Manges tells a story, vintage 1964, of the time Manges was visiting a ranch near Valentine in the Trans-Pecos. Some other guests had arranged to take a pickup out to hunt deer, and Manges, an ardent hunter, begged to go along, even though there was no room in the cab. The group agreed to let Manges ride in the bed of the pickup, but only after extracting a promise from him that he wouldn’t shoot until everybody was out of the truck and on the ground with an equal chance. Events unfolded predictably. Driver spots deer. Driver stops truck. Driver jumps out—and ducks for his life as Manges blazes away over his head. Afterward, no one was really angry. “That’s ol’ Clinton,” everybody agreed.

It still is Clinton. Manges has never been one to let anything stand in the way of something he wants. It was true when he was playing for small stakes, like deer, and it was true when he was playing for big stakes, like oil.

The obstacles keeping Manges from getting into the oil business in a big way in the summer of 1974 were property and money. He had the 107 marginal wells he’d won from Mobil, and he had mineral interests in thirteen counties, but the biggest of his properties were the Guerra lands—which, since he was merely a co-owner of the minerals, were his only to lease out rather than to develop for himself. Even if he’d had a hot property, he didn’t have the money to underwrite an extensive drilling program. By the end of the summer Manges had found the solution. It was supplied by his third mentor, the master of oil and gas wheeling and dealing, Oscar Wyatt.

As with Lloyd Bentsen and George Parr, Manges’ connection with Wyatt went back a long way. Wyatt had had a hunting lease on a portion of La Coma ranch when Manges was the owner. In the intervening twenty years, Wyatt’s career was a model for Manges. Wyatt gained a foothold in the gas business by attacking the big companies (in his case, pipelines) that imposed their will on landowners. One of his first leases was on the Duval County Ranch, under its old ownership. His big break came through the strength of his political connections, which he used to land lucrative gas supply contracts for San Antonio, Austin, and Corpus Christi. Most of all, he let nothing stand between him and a good deal. Even though four million Texans depended on gas supplied by his utility company, he sold off precious reserves to improve Coastal’s bottom line. He was betting on the come, betting that he could always make a better deal if he had to. Time proved him right, though he had almost lost everything along the way. All of these footsteps Manges would follow. The lesson of Wyatt’s career was make the deal now and take care of the consequences with another deal. And that is exactly what Clinton Manges did in September 1974. He made a deal with Oscar Wyatt.

A Coastal subsidiary called Gas Producing Enterprises loaned Manges $2.8 million and later increased the amount to $5 million. Manges pledged to spend at least $100,000 a month exploring for oil and gas until his return reached $500,000 a month. Wyatt’s company had a seven-year option to buy the oil and gas produced from all the Manges lands in the thirteen counties.

It was up to Manges where to drill; if GPE wasn’t satisfied with the way Manges was developing the property, however, Wyatt’s company had the right to take over. The deal was akin to a bet, with Manges wagering his minerals against Wyatt’s money that he could strike it rich before the money or Wyatt’s patience ran out. (The deal that began with a bet ended with a bet. Some years later Coastal decided that Manges could pay off his $5 million debt with the future delivery of 115,000 barrels of oil—an agreement that in effect had both parties speculating on the price of oil. It went down and Manges won.)

On the surface the Manges-Wyatt deal seemed harmless enough, but the Guerras thought otherwise. If GPE had the right to take over Manges’ minerals, what other oilman would risk taking a lease from him? It seemed to them that the GPE deal allowed Manges to lock up the Guerra lands for seven years without paying them the bonus that goes along with a traditional lease. The transaction was a work of genius, the genius of the consummate land trader, for it was impossible to say for certain whether the Guerras had been cheated. But they decided to find out. Besides, there had to be some reason why no one wanted to lease the property. A year after the GPE deal, Joe Guerra filed suit against Clinton Manges, his former ally.

The Wyatt loan temporarily eased Manges’ money problems, and he soon solved his property problems as well. In 1975 he got a promising farmout (similar to a sublease) from ARCO on 10,000 acres in Zapata County. But Wyatt’s money soon proved to be insufficient. Manges was drilling a dozen wells and more, running up bills beyond his ability to pay. Another ARCO farmout on the Duval County Ranch was eating up even more of the Wyatt loan. Manges had to get more money, and he knew just where to get it. He turned to his own banks.

Minding the Candy Store

To adopt a description used by one of Manges’ lawyers, Manges was unable to resist treating his banks as though they were candy stores and he had a sweet tooth. In addition to the Rio Grande City bank he had acquired from the Guerras, Manges also owned the Groos National Bank in San Antonio. He bought it in 1971 by applying a proven method—exploiting a split among stockholders brought on by the firing of a bank officer—but not until 1973 did he gain full control, after beating federal banking officials who were fighting his takeover because of his old felony conviction. Manges was not an officer or a director of either bank, just the major shareholder (92 per cent in Rio Grande City, 100 per cent at the Groos), but in subsequent civil suits and congressional investigations, federal officials had no doubt that the bankers were acting on his orders. And the essence of those orders was to make the deal now—support Manges’ drilling activities in every way possible—and take care of the consequences, including violations of federal banking rules, with another deal.

The Rio Grande City bank first came to the attention of federal bank officials in 1974 because of the concentration of loans to Manges’ associates. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation told the bank to clean up the loans; the bank’s response was to make even more. The big splurge came in the first half of 1976, when Manges’ Zapata County exploration activity neared its zenith. The bank made seven Manges-related loans, each of which exceeded the bank’s legal lending limits to individuals, including one for $350,000 to Manges himself. Those and other insider loans, the FDIC later charged, went to finance Manges’ oil and gas exploration; they were really pass-through loans to Manges himself. There were also unsecured loans, loans with inadequate collateral, loans to cover overdrafts, new loans to borrowers whose earlier loans had been charged off as uncollectible, loans to Manges’ wife, loans to Manges’ brother, loans to Manges’ son-in-law, loans to Manges’ accountant, loans to Manges’ friends, loans to a new Manges partner—so many loans that they represented 22 per cent of all the dollars loaned by the bank.

The Groos National Bank was no different. Shortly after taking control of the bank in the spring of 1973, Manges contacted an officer at a bank the Groos did business with, reminded the officer that the Groos was a big customer, and asked him to place the bank’s insurance with the agency Manges suggested. The answer was no, but in a few days Manges was back with another proposition. He wanted a loan, secured by stock owned by Mrs. Manges. This time the answer was yes, but before the paperwork was finished, the officer got a tip from someone at the Groos that Mrs. Manges didn’t own the stock; Manges wanted the money to buy the stock. Manges vehemently denied the story, but the officer called off the deal. Before long, the Groos took its business elsewhere.

Federal officals were constantly on Manges’ trail, but he always managed to stay one step ahead of them. After failing to thwart his takeover of the Groos, they got him to sign an agreement in November 1973 limiting his self-dealing. When the bank violated that, they got a cease-and-desist order. The Groos went right on wheeling and dealing. Finally the government obtained an injunction against any extension of credit to Manges, his relatives, and a long list of associates. But Manges’ oil ventures were devouring his cash. He found one last way to get money out of Groos National.

The case of Grady Wooldridge is by no means unique. Wooldridge, an Austin contractor, was hired to build a bunkhouse and cookshack at the Duval County Ranch in 1976. Wooldridge met with Manges on the job, but everything else was handled through an intermediary named Perry Horine, an old friend of Manges’. Within a few months the ranch company fell behind in its payments to Wooldridge by $27,000. Horine had the answer: Wooldridge should go to the Groos and borrow the money; Manges would pay off Wooldridge’s note when his cash flow improved. There was a catch: Wooldridge should borrow not $27,000 but $69,000. Part of the money would go to pay off another Manges debt. There was another catch: Manges did not guarantee Wooldridge’s note in writing. It may seem astonishing that anyone would agree to such a deal, but Wooldridge—and others who fell into the same trap—had bank notes of their own coming due elsewhere and a lot of money invested in Manges projects. They felt they had no choice but to go to the Groos and hope for the best. In fact, Wooldridge was a small-timer compared with another borrower at the Groos. The man who supplied Manges’ pipe is currently suing him over Groos loans totaling $1.2 million.

Despite the frantic wheeling and dealing, Manges slipped deeper and deeper into debt. In the Zapata County oil patch Manges was bringing in some wells, but they didn’t produce enough to pay for the all-out drilling he was doing. Not even his banks could supply enough capital to pay for the operations. Anyone who wants a short course in what is involved in drilling for oil and gas can learn everything there is to know by going to the squat, sagging Zapata County courthouse and looking at the list of plaintiffs who sued Clinton Manges for unpaid bills in the late seventies: roughnecks, well servicers, pumpers, drilling contractors, equipment rental companies, water haulers, mud suppliers, pipe servicers, tong operators, well loggers—nineteen suits for unpaid bills, plus another nine filed in Laredo.

There was more trouble in Jim Hogg County. Manges lost the second Guerra case, disastrously. The jury decided that even before the Wyatt loan Manges had had the secret intention of developing the Guerra lands for himself rather than leasing them out, as he was legally obligated to do. The loan, the jury said, was “in willful disregard” of the Guerras’ rights. (By the time the case came to trial, Manges had indeed leased 25,000 Guerra acres to himself on terms highly favorable to him and highly unfavorable to the Guerras.) The jury canceled the self-dealing, socked Manges for hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages, and worst of all, stripped him of the right to lease the Guerras’ half of the minerals in the future.

Still more bad news came out of Corpus Christi. One of the aggrieved oil operators in the pollution suit went to federal court, charging that Manges and Carrillo had conspired to deprive him of his civil rights. Manges came up with an ingenious defense—a judge was immune from suit and Manges contended that the immunity protected anyone who dealt with a judge. But the U.S. Supreme Court wouldn’t buy it, and ultimately Manges paid $200,000 to settle the suit.

At the northern end of the brush country, things were falling apart for Manges even in Duval County. The Duke of Duval was dead by his own hand. Manges had broken with Parr shortly before the end in 1975, siding with O. P. Carrillo in a feud that reached its climax one day when Manges was at Parr’s house. Parr snatched a machine gun and rushed out with the announced intention of shooting Carrillo. (Manges got to Carrillo first.) A year later Carrillo, impeached and indicted, was out of power. For the first time, Manges had to take lawsuits in Duval County seriously—and soon there were dozens of them, most for unpaid bills related to still more drilling activities. Other creditors were after him in Alice and Corpus Christi. It didn’t take Manges long to find out how different things were going to be without Parr and Carrillo. In 1977, two years after Parr went to his grave, Manges received the unkindest cut of all. Duval County sued Clinton Manges and his ranch for delinquent taxes.

Courting the Court

Where was Manges to turn? Besieged on all sides, he sought refuge in the lessons of South Texas. The idea that he had overextended himself, bet too much on the come, gambled and lost, was foreign to him. By the old Duval County standards, those explanations were mere apocrypha; “everything is politics and politics is everything” is the revealed truth. If government was not for him, then somewhere politics had to be turning it against him.

He knew just where it was, too: the Texas Supreme Court. If the court hadn’t historically favored the oil company at the expense of the landowner, if Texas oil and gas law had forced Mobil and the other companies operating on his ranch to develop it properly, he wouldn’t be so strapped for cash in the first place. From the time he bought the Duval County Ranch, Manges had been convinced that there was a huge gas play in the Deep Wilcox Trend, 20,000 feet and more below the surface, but the companies wouldn’t spend the millions necessary to drill a deep test well. Yet the law allowed them to keep the land—his land—tied up so that he couldn’t lease it to someone willing to try. Nor did the law require the companies to explore and drill extensively; one well could tie up thousands of acres as long as the company was making a profit from that well. Consequently, some areas of the Duval County Ranch remained unexplored, half a century after most of the leases had taken effect. The only way to fight the companies was to prove that they had not developed the property reasonably, and that required finding geologists who would testify against the oil company’s geologists—as hard to find as doctors who will testify against other doctors.

Manges had been trying to win the favor of the court for years. On trips to Austin he’d been known to drop by the court building, visiting one justice’s office after the other. Soon after Manges moved to Duval County, a district judge in Sinton invited several justices to go hunting; only after they arrived at their destination did the justices discover that they were on the Duval County Ranch and who their real host was. But the law continued to favor the oil companies, and the only way to change the law was to change the court. And the best way to do that was through campaign contributions. He would see the landowner triumphant yet.

There was just one anomalous note. The very sins Manges accused the big oil companies of committing against landowners—holding back money, not developing leases, polluting the surface—were exactly what the landowners were accusing him of doing on the ARCO farmout in Zapata County. Landowners discovered that he had failed to pay royalties. The president of the old Duval County Ranch company, checking up on Manges, also found that he had withheld royalties due the former shareholders from new wells on the ranch. One Zapata owner sued because Manges hadn’t developed his tract properly, putting only one well on 1053 acres. “What Mobil did to him, he’s doing to us,” the landowner said. ARCO took over the accounting. It also sued Manges for failing to clean up the surface damage to well sites. The landowners’ frustrations were summed up in a letter one of them wrote to ARCO: “Your company has got our property in a hell of a mess by farming out portions of this lease to a damned crook like Clinton Manges.”

A Race Against Time

He was in a desperate race, a race against time. In a 1977 list of unpaid creditors (and it was not a complete list at that), Manges admitted to 167 overdue accounts, most of them owed to oil field businesses but at least a dozen to law firms and another thirteen to governmental bodies for delinquent taxes. Some creditors had already filed suit to get their money, and others would follow. The collection process confronting Manges was swift and inexorable: an adverse judgment without the formalities of a trial; then, if the money was still not forthcoming, a court-ordered sale of his assets. His empire was in utter peril.

Manges’ problem was more one of philosophy than one of money. His financial statement at the time showed $67 million in assets ($24 million for the Duval County Ranch, $33 million for oil and gas properties like the Guerra lands, and $5 million for the Groos Bank were the main items) and only $27 million in liabilities ($19 million in loans and the rest in past-due bills). That left his net worth at $40 million. But cash flow was his problem. To pay his debts he would have had to sell land, and that was unthinkable. Land is power; one gets rich by accumulating assets, not by selling them.

Bankruptcy was out. Manges says that he went all out to pay everyone, that had he taken bankruptcy, his creditors would have had to settle for a fraction of what he owed them. (Some had to anyway; others in time collected their due.) But taking bankruptcy would also have meant putting his assets in the hands of somebody else, and such a choice was inconsistent with everything Clinton Manges stands for.

Borrowing was out. The longer his list of creditors grew, the shorter were his chances of getting a conventional loan. His own banks could no longer help him either. Federal officials had finally shut down the candy stores. In November 1976 the FDIC invoked a remedy it had not attempted since 1940: it canceled its insurance coverage on deposits at the Rio Grande City bank. Manges was—and still is—furious. “They seized that bank,” he says. To him the issue was not self-dealing but solvency, and indeed, the bank was still solvent when the FDIC pulled the plug. At the time Manges said the FDIC’s interest in the bank had been triggered by none other than John Connally, who as former Secretary of the Treasury had once been the nominal boss of the FDIC and who, Manges averred, was eager to embarrass a Democratic potentate in South Texas. (Conspiracy buffs, please note: the new owner of the bank was a partner of Connally’s in another bank.) In any case, once the insurance was gone, the state banking department had no choice but to close the bank and arrange for its sale. A year later, after deposits at the Groos had dwindled from a high of $69 million to less than $30 million, the FDIC told Manges that if he didn’t sell the bank, it too would be closed. He sold—to Oscar Wyatt.

Only one course was left open to Manges. He had to stall. He had to use the legal system the way a man sentenced to die uses it, not to achieve justice but to impede justice in every way possible. His normal method, a former Manges lawyer charged, became “not to repay his obligations until the creditor brings suit.”

In pursuing his delaying tactics, Manges did have one thing working for him: his total dedication to keeping his empire intact. It took a particular breed of man to withstand the pressure—to remain unyielding when several of his creditors themselves were forced into bankruptcy; when one died of a heart attack, forcing him to continue the fight against the widow; when it seemed as if all of South Texas was against him—but Manges was up to it. He is a man who cannot abide being forced; he insists on doing things in his time and in his way. In his office hangs a picture of an Indian chief, accompanied by a sign that says, “Around here there’s only one chief. Everybody else is an Indian.” The more his creditors tried to be chiefs, the more he was able to focus on the fight itself rather than on the merits of what he owed. In the end his bills became just another deal to be worked out. His instinct for trading exposed the weaknesses of his opponents. Most of them were less determined than he. They had no stomach for an all-out war with no end in sight. He could push them to the limit, and still they would settle for less than the full amount he owed, just to be rid of him.

All the while Manges was writing the book on how to frustrate creditors. It lies, uncollated and undistributed, inside scores of file folders scattered around the courthouses of the brush country. Everything is there except the chapter headings:

• Avoid service. One of the first steps in a lawsuit is to notify the defendant by serving him with papers—not a simple matter when he lives on a 100,000-acre ranch behind a high fence and a guarded gate and keeps an airplane handy. The Manges cases were filled with motions from lawyers to serve Manges by leaving the papers at the ranch headquarters rather than by handing them to him personally—but only after the traditional method had failed.

• Countersue. Unless Manges could shift the battle away from the invoices his foes had assembled to substantiate their claims, he had little chance to slow down the process of collection. So he sued his creditors right back, claiming overcharges or shoddy work. With a handful of exceptions, Manges’ countersuits offered no proof other than vague allegations, but it didn’t matter. They kept the ball in the air. The other side had to answer his contentions, then he got to answer theirs, and on it went. More time gained.

• Don’t cooperate. The rules of procedure include various methods designed to speed up lawsuits and narrow their focus. Each side can question the other’s crucial witnesses in advance. Each can ask the other to admit or deny certain basic facts so that the process doesn’t have to be repeated at a trial. But Manges frequently didn’t show up for depositions and failed to answer requests for admissions. That tactic touched off a new round of motions to compel a response. When he did answer, his inability to recall and his lack of knowledge of his own affairs were worthy of Watergate.

• Change attorneys. Manges went through as many as four lawyers on a single case—whether by design or whim it is impossible to say, but the effect was the same. Each change enabled him to win delays while his new lawyer familiarized himself with the file.

• Intimidate the opposition. If a creditor (or his lawyer) got tough with Manges, Manges got even tougher. Mustang Oil Tool Company filed a criminal complaint against Manges when a check for $57,000 bounced; he responded with a $1 million countersuit for false imprisonment and malicious use of process. (He lost.) Three creditors tried to force him into bankruptcy; Manges filed countersuits against them. Don McManus, a San Antonio attorney who represented one of the Guerras pressing a $419,000 claim against Manges, says a Manges operative made a take-it-or-else settlement offer in Manges’ presence—the “or else” being that Manges would file a grievance against McManus with the local bar association. McManus rejected the offer, and the bar did indeed get a complaint from Manges. It was dated four days before the meeting but postmarked four days after.

• If you can’t intimidate them, neutralize them. Manges has offered future employment to opposing lawyers, a tactic that worked for him during the first Guerra case. Among the lawyers he approached was Tony Canales of Corpus Christi (formerly the U.S. attorney in Houston), who was handling Duval County’s suit for delinquent taxes. “I can make more money suing you than I can defending you,” Canales told Manges.

• Juggle creditors. Remember the loan shark advertisements that used to be on the radio? Consolidate all those unmanageable little loans into one manageable debt, they advised. That’s what Manges did. While he still owed the Groos Bank, he ran up a $349,000 debt to an Oklahoma drilling contractor. The contractor went to the Groos, borrowed the money with the usual stipulation that Manges would pay off the loan, and used the money to pay Manges’ creditors. In return Manges gave him an option to do some drilling for himself on Manges’ land. Eventually the Oklahoman declined the option, though, and Manges had to come up with the money, which, of course, he couldn’t do. That led to a new lawsuit, but ultimately Manges solved the new problems in the old way. He hooked up with a wealthy fried-chicken entrepreneur named Joe Schero, who paid off the drilling contractor and a number of other Manges creditors in exchange for farmouts. Manges had brought in three wells on the land, but Schero was less fortunate. He drilled at least sixteen wells, all of them dry holes. Manges ended up with Schero’s oil refinery, and Schero ended up with a lawsuit against Manges, thereby joining the growing group of Manges’ associates who had fallen out with their former compatriot.

• Fight to the finish. If a creditor managed to outlast all this and get a judgment, he still faced the problem of collecting his money. Several reached the point of getting a court to order the sale of Manges’ land, but none actually saw it sold. Each time Manges found a judge to stop the sale—on several occasions, the order came not from the judge who had actually presided over the case but from a judge who presided in another territory. That happened twice in the Duval County tax case before a frustrated Canales got his own court order forbidding Manges or his ranch company from interfering with the sale. Then and only then did Manges pay up. When the state watchdog agency for judges, the Commission on Judicial Conduct, lectured the various judges who had helped Manges out, Manges filed a suit against the members of the commission. He lost.

It wasn’t only Manges’ creditors who got the full treatment; it was all sorts of people who had dealings with him, some in the most innocuous ways. In the spring of 1976 a fence separating the Duval County Ranch and a neighboring spread was in disrepair. The neighbor offered to supply the materials if Manges would provide the labor. The story may sound like something out of Robert Frost, but on this occasion a good fence did not make for good neighbors. While the fence was being repaired, some of the neighbor’s cattle wandered onto Manges’ ranch. Manges refused to return them and the neighbor sued. Manges sued right back. The neighbor, he said, had overstocked and overgrazed his pasture. The fence was strong enough to withstand cattle of “ordinary disposition,” but this hungry herd, casting covetous eyes on Manges’ sorghum-rich pasture, couldn’t control themselves and they broke through the fence. Manges offered to return the cattle—for $226,000. Eventually the neighbor wrote off his cattle rather than continuing the fight.