It is evening in America and Steve Stockman is pumped. Wearing a sky-blue button that says “I’m a Freshman and Proud of It,” the 39-year-old Republican congressman from the 9th District of Texas is basking in the glory of the government shutdown, proud on this December night that his colleagues, those fervent disciples of House Speaker Newt Gingrich, had spent another day showing their mentor and Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole and President Clinton a thing or two about standing firm and sticking to campaign promises. “I think finally, finally, the White House sees we’re serious,” Stockman says, delighted that the freshmen have brought negotiations to a standstill with their uncompromising demand for a balanced budget in seven years—and no dice to any temporary spending measures. Retirees may go without social security checks, veterans may go without benefits, welfare moms will just have to make do, but the freshmen have shown they will not be pushed around. “I felt pretty powerful there for a minute,” Stockman says to the young staffers gathered in his office’s reception area to watch an afternoon press conference given by freshmen replayed on the evening news. Hitching up his pants, Stockman harrumphs and postures, pretending to be…a congressman. “Wanna go out to dinner? I’ve got about three million dollars to spend.”

Stockman, with his ski-slope nose, elfin ears, and perpetually mischievous eyes, is on a roll. “I have shown great independence on the critical issues of our district,” he orates to his chief of staff, a prematurely gray young man by the name of Cory Birenbaum. “I’ve opposed the leadership on Mexico—” Stockman continues, a reference to his opposition to the government’s $20 million bailout of the Mexican economy. “And on Bosnia,” Birenbaum prompts.

“On Bosnia,” Stockman agrees, nodding as he cites his opposition to the deployment of U.S. troops in Eastern Europe.

“And on NAFTA,” suggests Birenbaum.

“NAFTA!” choruses Stockman, enchanted with the memory.

Hearing Stockman talk, it sounds pretty easy to be a congressman: Shut it down; close it up—that is what the voters want. Oh, Stockman has taken some missteps this first year in office—like last April’s big deal over the fax he had received from a militia group minutes after the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City (“I did the right thing. I handed it over. I wish I never did,” he says. “I wish it never happened”). And last June he had called the attorney general and the president murderers in a story for Guns and Ammo magazine about the Second Amendment and the siege of the Branch Davidian compound outside Waco (“These men, women and children were burned to death because they owned guns that the government did not wish them to have,” he wrote). And there has been an almost total lack of enthusiasm, during this shutdown period, for Stockman’s December call for a thorough investigation of Alfred Kinsey’s fifty-year-old report on human sexual behavior. But, so what? Everyone learns by doing, and Steve Stockman would be the last man to take exception to that rule. “This,” he says, in an eager manner that was the result of the shutdown in particular and governing in general, “is pretty exciting.”

“The leadership has told me, ‘You’re too honest. You’re too open,’ ” Stockman said earlier that same day. “The way I see it, the nail that is stuck up highest gets pounded. If you stand up for your principles, you’ll get hit,” he added, pounding his own head for emphasis. At that time, things were looking a little grim. Stockman was fighting the flu, contracted because no freshman Republican, no matter how contagious, could bear to lose even one sick day in service to Newt’s Contract With America. Then there was the media, who seemed determined to paint Stockman and his affinity group as stubborn, surly three-year-olds (the previous evening, Nightline had double-entendred Stockman and his colleagues with a show titled “Those Revolting Freshmen”). But most painful of all was facing a reporter anxious to assess Stockman’s legislative career, which, nearing the end of his first year in Washington, had been the subject of—at best—mixed reviews.

Stockman likes to call his story “The American Dream.” In 1994 the occasional accountant and born-again Christian miraculously defeated Jack Brooks, a liberal legend who had just about ossified after 42 years of service to the region that stretches from Clear Lake to the Louisiana border. Stockman’s election was a reflection of the American electorate’s deeply felt but squirrelly notion that the best alternative to seasoned politicians was neophytes. Unbeholden to special interests, unschooled in the wicked ways of Washington, unburdened by party history, these freshmen would, the voters believed, unflinchingly cut spending, lower taxes, shrink bureaucracies, and reform their profession. They could triumph where career politicians had failed. And then because they were not career politicians, they would ride out of town and make room for another cadre of fresh recruits. “We all had the novel idea that we’d come up and keep our word,” explained Stockman.

He did and they did—slimming congressional perks as they threaten to snatch food from welfare babies’ mouths—and there’s been hell to pay ever since. Stockman, it turns out, has been the most extreme example of the politician without portfolio: a man with no past, few ties, and a just-say-no ideology. That has meant, in a federal government facing tax, welfare, and health-care reforms, not to mention the maintenance of order in the post—cold war era, an allegiance to . . . abdication. The freshmen have usually been linked to the Republican right-wing fringe—to the rabid, gun-toting fundamentalists—but they have more in common with the people who call talk radio programs: Isolationist, uninformed, and impulsive, the freshmen have not been as concerned with traditional questions of more versus less government as they have been with less government versus no government at all. Devoted to getting their way, these freshmen—and their leader—have created one of the most divisive congressional terms in history. (In January, over the vehement objections of many freshmen, the Republican leadership and Clinton agreed to spending measures that would temporarily reopen the government.)

Not surprisingly, the freshmen in general and, most notably Stockman, have received nothing but contempt in more-seasoned quarters on Capitol Hill. “A complete nut” was the way one political reporter described him. “Off the reservation,” said another. “An embarrassment,” according to one congressional aide. “Not the brightest bulb on the Christmas tree,” asserted a Democratic party operative. Republicans who defend Stockman assert that he has been treated unfairly because of his outspokenness. “He’s vocal in his convictions,” said fellow congressman Lamar Smith. Others don’t even try to defend him: “He’s a Republican,” said Edward Chen, the vice chairman of the Harris County Republican party. “As a Republican, he’s on our ballot. And that’s about the situation.”

Brooding over his poor notices, Stockman looked wounded. In his mind, he is a reasonable man who has been treated unreasonably. Attacked for ethical improprieties and his loyalty to the militia movement, Stockman claimed to be a victim of sloppy reporters: “They will take clippings and they will regurgitate.” He asserted that his ties to the Religious Right have been greatly exaggerated: “It’s a sad day in America if you go to church and you’re conservative and that’s a pejorative.” He has even been a victim of the political polarization he has helped foment: “The e word,” he said. “‘Extremist.’ The Democrats are testing themes. It’s just like us calling everybody a liberal. We’ve got ‘liberal.’ They’ve got ‘extremist.’” Pondering such finer points of the political game, Stockman grimaced at the seriousness of Washington. “These people have lost their sense of humor,” he said. “I used to be much more jovial. People here are so tightly wound.”

“Tip O’Neill once said that all politics is local,” Steve Stockman remarked, citing the familiar bromide as he strode through the tunnels underneath the Capitol buildings to cast a vote on the House floor, “but to me, all politics is personal.” It was later that same morning, and his gloom had cleared, along with his sinuses. “Did I get invited to your office Christmas party?” he ribbed a fellow congressman, who looked queasy at the thought. Stockman was pleased that the freshman congressmen came off well—that is, not crazy—on Nightline and that another news report actually suggested that Gingrich was now beholden to them. Revitalized, the rookies planned to meet later in the day to press their balanced-budget plan. Stockman’s step was as light as a jig; for him, the shutdown equaled progress.

From Stockman’s overwhelmingly negative news clippings, it is possible to picture him as a combination of Joe McCarthy, Pat Robertson, and Rambo, but to spend the day with him is to see how much closer he is to Jim Carrey. As those somber Depression and World War II veterans have been eclipsed by baby boomers in government, a new kind of political archetype has emerged: the politician as adolescent. Along with Clinton, the great vacillator, and Gingrich, the great pouter, now there is Stockman, the cutup. Energetic and wisecracking, Stockman never met a stranger—“He’s a nice guy,” is his favorite compliment. (The president, who belongs to another clique, is by definition not a nice guy.) His diet consists mainly of junk food. His speech is full of teenage colloquialisms—“She’s gonna jolt him, dude,” he said of a staff member’s current girlfriend—and his attention span is ephemeral. “I felt books were too old,” he said of the “ferocious reading” he did in his twenties. “Magazines were quicker with the information. By the time a book was published, it was not current.” His intellect has been shaped by TV. “Ritalin—that’s my next crusade,” he said, inspired by a television show on the drawbacks of the attention-deficit disorder drug.

Substantive questions are the setup for a joke. Asked for his stand on managed care, the centerpiece of both parties’ health-care reform packages, Stockman winked and said, “We’re workin’ on it.” Asked whether he believed that he and Gingrich had effected a revolution: “That depends on whether we’re here or not in ten months,” he quipped. When Stockman avowed that all politics is personal, he meant it quite literally—all things that have touched his life. And because his experience has been narrow, his politics are too. Health care? International monetary systems? Regulating burgeoning telecommunications networks? “My core value is the belief in the American family and the belief that they make better decisions than I make for other people,” he said. Few who study Stockman’s background could disagree.

Back in his office a few hours later, Stockman was, again, expansive. He had worked through lunch in conference with other freshmen, unperturbed that the shutdown had hit home. “My wife works at NASA, and she’s furloughed,” he said, hanging up from a phone call. But in solidarity with his freshman colleagues, he had refused to give ground to the president. “What makes you think [Clinton is] gonna keep his promise?” Stockman said he had asked them when Clinton briefly appeared willing to compromise. “I grew up on the street, and I know when we’re being hustled.”

Stockman’s experience “on the street” had only recently become public. It was revealed shortly after the election that in his twenties the Michigan native had spent about six months living at the Fort Worth Water Gardens, too broke and ashamed to ask a Texas relative for help. Stockman now describes that period as an introspective one that led to new questions and newfound maturity (“Why am I here? Is there more to life than partying?”), but the metaphor of homelessness can be applied to his life as a whole. Theoretically, voters turned out Jack Brooks because he was too much of an insider; what they got was his polar opposite: a lost man.

Like so many people who came to Texas in the late seventies and early eighties, Steve Stockman was a refugee from the Rust Belt. He was the fourth of six children born to two Michigan schoolteachers, who were evangelical Christians. Stockman has often described himself as the family black sheep; uninterested in academics, he dropped out of college. “I subscribed to the partying syndrome,” he said. He drove junkers, painting one with house paint so his friends could carve their names into it. Stockman spent more than one weekend in jail for traffic violations, and once, after a girlfriend hid Valium in his underwear before he was incarcerated, he was charged with possession of a controlled substance, a felony that was later dropped. His legal problems had no effect on his social life: Stockman, joking, told a Dallas Morning News reporter that he always had his share of “hot-looking babes. I was the studerino.” He was the quintessential good-time guy: For the flight to his sister’s wedding, Stockman showed up wearing a T-shirt and a bathing suit.

Friends married and started careers, but Stockman remained stuck in party mode. He lived briefly with a brother in Madison, Wisconsin, but even his brother finally had to evict him. After spending one cold night in a bus stop, he decided to head for warmer climes. “So,” he told the Morning News, “I took a bus to Texas.” It was there, at the age of 23, that he “hit bottom,” sharing the Water Gardens with drug-abusing war veterans and the mentally ill.

The story of Stockman’s life takes on the gloss of maturity at this point. “There’s a program on The Learning Channel that talks about significant time changes in history,” Stockman said. “I realized I couldn’t follow the philosophy of the sixties. Living free—there’s no such thing.” In 1980 he moved to Houston and worked at various odd jobs. At one time he ran a business called Stephen S. Studios in a sexually oriented section of Montrose, a fact that has given opponents no end of pleasure. (“It was a house-painting business,” Stockman said, exasperated.) Then, in 1984, while eating pizza and channel surfing with his girlfriend, Patti Ferguson, Stockman caught the Reverend John Bisagno of the First Baptist Church of Houston delivering a sermon. Thanks to the urging of his wife-to-be—and the help of cable TV—Steve Stockman put his life in Jesus’ hands.

Married in 1988, the former life-of-the-party got serious, eventually graduating from the University of Houston–Clear Lake. With his new resolve, Stockman joined the local chapter of the Young Conservatives of Texas, moving through the ranks to become state chairman. Perhaps it is merely consistent that Stockman’s inspiration to run for office came from watching TV: He maintains that he was angered by Jack Brooks’s mistreatment of Reagan-era renegade Oliver North during televised congressional hearings. But Stockman’s political ambitions got their biggest boost from an advertisement that ran on radio and in newspapers at the time. A company calling itself the United States Citizens Association was offering to “help finance and provide expert campaign help to public-minded candidates who will run against Jack Brooks.” The ads were actually financed by the Suarez Corporation, a controversial mail-order business that had targeted Brooks after he attempted to regulate the industry. Bent on revenge, the company kicked in $80,000 in what it called a loan for Stockman to run against him. Unfortunately for Suarez, he lost the primary in 1990. But the candidate was hooked—and, coincidentally, he had nothing else to do. With evangelical churches providing organization, Stockman won the Republican primary in 1992, and in 1994 he challenged Brooks again.

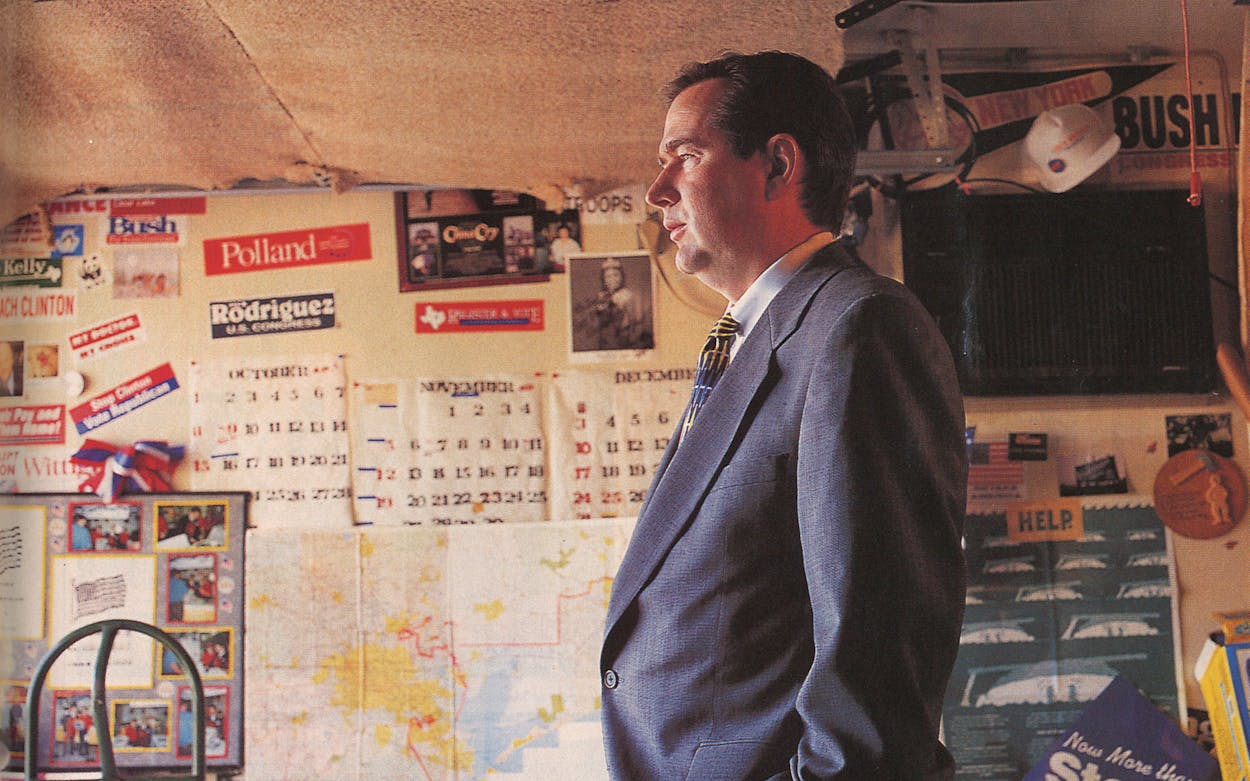

One more time, Stockman, who ran a shoestring campaign from his garage, owed a momentous transformation in his life to outside forces: a change in the political climate. Owing to social and economic pressures exploited by everyone from Rush Limbaugh to Patricia Ireland, the president of the National Organization for Women, the country was balkanizing. East Texas was not immune: Even though Brooks possessed unparalleled power in the House and had graced his district with countless jobs, his constituents decided that he was ineffective and out of touch. The fact that he allowed a bronze statue of himself to be erected at Lamar University was proof that he had become too grand; his support of Clinton’s crime bill, which contained stiff gun-control provisions, was an insult to a region that—as was oft repeated—had more gun dealers than did the state of New York. It was, in fact, gun owners who became devoted to Stockman, even though he admitted that he had never owned a gun. “But I am interested in personal freedom,” stressed Stockman, as he headed to Washington with 52 percent of the vote.

Sunset, outside the Capitol building. A giant Christmas tree glistened in the foreground, the Washington Monument glows on the horizon. The freshman Republicans descended the Capitol staircase en masse for a press conference that would later air on the evening news. Stockman, last to arrive, scurried to take his place behind the podium with his colleagues. It was frigid outside, and reporters were rumbling about the hundreds of thousands of people who will be without funds because of the shutdown. But the freshmen—a few with freezing children in tow—had chosen this spot to show their strength and solidarity. One congressman explained that balancing the budget was “giving our children and grandchildren the best Christmas present they could hope for.” Another resurrected the themes of 1994, mentioning “the value of trust, of honoring commitments.” Still another intoned, “Keeping your promises is not ‘extreme.’ We were determined to change business as usual in Washington and that involves keeping our promises.” Steve Stockman, lost in the crush, kept his trap shut.

Just twelve short months ago, he was described by the Washington Post as a leader of the freshman class. Now even the other freshmen treat Stockman as if he has congressional cooties. Perhaps it was psychologically imperative that he descend from head of the class to class clown—clearly, he’s still most comfortable in the role of black sheep. Friends in Congress insist that the impressionable Stockman just got in with the wrong crowd—meaning his constituents on the right-wing fringe. Whatever the reason, Stockman torpedoed his grab for respectability by acting like a kid in what used to be a grown-up’s job.

Truth be told, Stockman was treated unfairly in his first and most famous national appearance. In the confusion that followed the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City last April, his office received a fax detailing the time and place of the attack that killed 169 people. Stockman, unlike hundreds of other public officials who had also received the fax, turned it over to the authorities. But in defending himself—it was initially reported that he had received the fax before the explosion—Stockman refused to budge from his allegiance to a repeal of the assault weapons ban or his loyalty to militia groups. The nation needed reassurance; Stockman stubbornly stuck by his clique: “Just because somebody’s part of a group, we cannot blame the whole group,” he said.

Then, too, Stockman was drawn to dramatics over substance, making himself a mouthpiece of the paranoid. In March, for instance, he had written a letter to Janet Reno, suggesting that a secret compound at Fort Bliss was being created to spy on militia groups (“Information is scarce, but…” his letter on the subject began). In June Guns and Ammo published Stockman’s zany pro-gun screed (he later contended that the periodical used the story “to promote the magazine at my expense”). Last fall, as first reported in Roll Call, he got into a very public squabble with the mother of a murder victim who refused to allow Stockman to name a bill repealing almost all gun-control laws after her son. He did not seem to understand why members of the public would be offended by his appearance on Radio Free America, which is widely believed to be anti-Semitic: likewise, the prayer meetings that began each day in his congressional office, and the staff and consultant links to the John Birch Society and the Gun Owners of America. Even though the Gun Owners of America has been linked to white-supremacist organizations, Stockman does not see the group as extreme. “The Gun Owners of America and the NRA are close,” he insists. “Both are pro- gun. One group is small; one is huge.”

And he did not learn from his mistakes. In December, while much of Congress was mired in budget negotiations, Stockman provided the comic relief. The Family Research Council, a right-wing group long opposed to sex education in schools, had shown him a video attacking the research of Alfred Kinsey. The Children of Table 34, narrated by Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., revealed that Kinsey had relied on a pedophile’s diary to research orgasm rates in young boys. After viewing the film, Stockman called for a government investigation of the report, claiming that all sex education in America should be halted because it was based on Kinsey’s faulty research. In a letter to his colleagues, Stockman was even more rabid: “Our children have been taught that . . . any type of sex is a valid outlet for their emotions. They are taught that the problem with sex is not that it is wrong to engage in homosexual, bestial, underage, or premarital sex, but that it is wrong to do so without protection.”

Throughout the year, Stockman also faced ethical misconduct charges that amounted to one almost every two months. The Houston Chronicle caught him fudging his education and work history. He returned a campaign contribution when it was discovered that the “constituent” was a four-year-old. Two investigations and one inquiry by the Federal Election Commission have been launched against him: The first investigation, involving a loan he made to his campaign, was dismissed. The inquiry involves his failure to repay the $80,000 debt to the Suarez Corporation, the mail-order house that financed his first race. The other investigation, which is still pending, surrounds Stockman’s production of campaign literature disguised as a neighborhood newspaper (SERVICEMEN DON’T WANT SODOMITES IN THE MILITARY was one headline). His actions weren’t venal as much as they were careless, the actions of someone who just couldn’t be bothered with rules. And the cumulative effect of Stockman’s activities has not been hard to divine. Even though he did work on some important projects—a bill to end the sale of alcohol to minors in Louisiana, thus lowering the number of highway deaths in Texas—he has rendered himself powerless in Congress. “When his bills come up,” said one Democratic operative, “they’re basically DOA.”

“One thing is for sure,” Stockman says, echoing another freshman promise and referring to his predecessor, “I’m not gonna be here forty-two years. I’ve got a life.” It is the end of a full day. Darkness has settled over the capital, and Stockman is on his way to meet a colleague, Frank Cremeans, for dinner. Stockman is a big fan of Cremeans’, a Republican freshman from Ohio who also enjoys the support of anti-government forces. Stockman says with a laugh that Cremeans raised more money at a recent Stockman fundraiser than Stockman himself: “He tells them, ‘I’ve got a list of who’s goin’ to heaven, and you’re not on it.’”

Cremeans, a slight, white-haired man in a snug-fitting suit, meets up with Stockman in the tunnel. “He’s one of my favorite guys,” Cremeans says, slapping the younger man on the back.

“Because I’m a lost puppy,” Stockman says, grinning, “an orphan.”

“When Newt talked about Boys Town, all I could see was Steve’s face,” Cremeans says, grinning back.

The men arrive at the Senate dining room to find it closed but sweet-talk the employees into a lonely guy’s dinner of hamburgers, Senate bean soup, and apple pie à la mode, which is delivered in and eaten in reverse order. They lament the absence of fundraisers this time of year. “Frank and I think dinner is a six-inch plate with a toothpick,” Stockman says, making a circle with his hands. They compare presidential candidates—Stockman backs Phil Gramm, Cremeans supports Steve Forbes—and they worry out loud about the congressional gift ban that will soon take effect. “I’m nervous,” Stockman says, thinking of his Democratic adversaries. “I’m afraid we’re gonna get set up.”

Of his own race this fall, Stockman is buoyant. He has no primary opposition and weak Democratic contenders. And, right wing or no, the money that always flows toward incumbents has begun moving his way. Exactly one bank contributed $1,000 to Stockman’s 1994 campaign; this year, thanks to his support of a bill that would essentially repeal Texas’ homestead exemption and allow second mortgages, he collected $10,000 in banking contributions from January to June.

Finished with the meal, the two men sit back, slumped in their chairs, hands in their pockets, pleased with themselves.

“Here it is, twenty to eight and all we’ve had is two pieces of pizza,” Cremeans says, dinner having apparently made no impression.

“All these perks,” Stockman gripes, in on the joke.

The discussion shifts again to politics, fundraising, and publicity. “We’ve been on the front page of the London Times twice,” Stockman says proudly. “First for our fax and then for Kinsey.”

“Steve,” Cremeans says, his voice imbued with wonder, “you’re a momentmaker.”

Hearing him, Stockman grins, glad to be home at last.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Steve Stockman

- East Texas